Trans fat

| Types of fats in food |

|---|

| See also |

Trans fats, or trans-unsaturated fatty acids, trans fatty acids, are a type of unsaturated fats that occur in small amounts in nature but became widely produced industrially from vegetable fats for use in margarine, snack food, packaged baked goods and frying fast food starting in the 1950s.[1][2] Trans fat has been shown to consistently be associated, in an intake-dependent way, with increased risk of coronary heart disease, a leading cause of death in Western nations.[3]

Fats contain long hydrocarbon chains, which can either be unsaturated, i.e. have double bonds, or saturated, i.e. have no double bonds. In nature, unsaturated fatty acids generally have cis as opposed to trans configurations.[4] In food production, liquid cis-unsaturated fats such as vegetable oils are hydrogenated to produce saturated fats, which have more desirable physical properties, e.g. they melt at a desirable temperature (30–40 °C). Partial hydrogenation of the unsaturated fat converts some of the cis double bonds into trans double bonds by an isomerization reaction with the catalyst used for the hydrogenation, which yields a trans fat.[1][2] Although trans fats are edible, consumption of trans fats has shown to increase the risk of coronary heart disease[5][6] in part by raising levels of the lipoprotein LDL (often referred to as "bad cholesterol"), lowering levels of the lipoprotein HDL (often referred to as "good cholesterol"), increasing triglycerides in the bloodstream and promoting systemic inflammation.[7] Trans fats also occur naturally in a limited number of cases. Vaccenyl and conjugated linoleyl (CLA) containing trans fats occur naturally in trace amounts in meat and dairy products from ruminants. Most artificial trans fats are chemically different from natural trans fats. Two Canadian studies[8][9] have shown that the natural trans fat vaccenic acid, found in beef and dairy products, could actually be beneficial compared to hydrogenated vegetable shortening, or a mixture of pork lard and soy fat,[9] by lowering total and LDL and triglyceride levels.[10][11][12] A study by the US Department of Agriculture showed that vaccenic acid raises both HDL and LDL cholesterol, whereas industrial trans fats only raise LDL without any beneficial effect on HDL.[13] In light of recognized evidence and scientific agreement, nutritional authorities consider all trans fats as equally harmful for health[14][15][16] and recommend that consumption of trans fats be reduced to trace amounts.[17][18]

In 2013, the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued a preliminary determination that partially hydrogenated oils (which contain trans fats) are not "generally recognized as safe", which was expected to lead to a ban on industrially produced trans fats from the American diet.[2] On 16 June 2015, the FDA finalized its determination that trans fats are not generally recognized as safe, and set a three-year time limit for their removal from all processed foods.[19]

In other countries, there are legal limits to trans fat content. Trans fats levels can be reduced or eliminated using saturated fats such as lard, palm oil or fully hydrogenated fats, or by using interesterified fat. Other alternative formulations can also allow unsaturated fats to be used to replace saturated or partially hydrogenated fats. Hydrogenated oil is not a synonym for trans fat: complete hydrogenation removes all unsaturated fats.

History

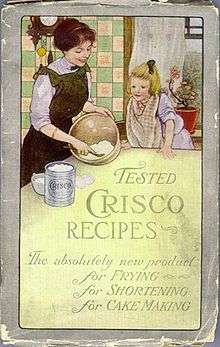

Nobel laureate Paul Sabatier worked in the late 1890s to develop the chemistry of hydrogenation, which enabled the margarine, oil hydrogenation, and synthetic methanol industries.[20] Whereas Sabatier considered hydrogenation of only vapors, the German chemist Wilhelm Normann showed in 1901 that liquid oils could be hydrogenated, and patented the process in 1902.[21][22][23] During the years 1905–1910, Normann built a fat-hardening facility in the Herford company. At the same time, the invention was extended to a large-scale plant in Warrington, England, at Joseph Crosfield & Sons, Limited. It took only two years until the hardened fat could be successfully produced in the plant in Warrington, commencing production in the autumn of 1909. The initial year's production totalled nearly 3,000 tonnes.[24] In 1909, Procter & Gamble acquired the US rights to the Normann patent;[25] in 1911, they began marketing the first hydrogenated shortening, Crisco (composed largely of partially hydrogenated cottonseed oil). Further success came from the marketing technique of giving away free cookbooks in which every recipe called for Crisco.

Normann's hydrogenation process made it possible to stabilize affordable whale oil or fish oil for human consumption, a practice kept secret to avoid consumer distaste.[24]

Prior to 1910, dietary fats consisted primarily of butterfat, beef tallow, and lard. During Napoleon's reign in France in the early 19th century, a type of margarine was invented to feed the troops using tallow and buttermilk; it did not gain acceptance in the U.S. In the early 20th century, soybeans began to be imported into the U.S. as a source of protein; soybean oil was a by-product. What to do with that oil became an issue. At the same time, there was not enough butterfat available for consumers. The method of hydrogenating fat and turning a liquid fat into a solid one had been discovered, and now the ingredients (soybeans) and the "need" (shortage of butter) were there. Later, the means for storage, the refrigerator, was a factor in trans fat development. The fat industry found that hydrogenated fats provided some special features to margarines, which allowed margarine, unlike butter, to be taken out of the refrigerator and immediately spread on bread. By some minor changes to the chemical composition of hydrogenated fat, such hydrogenated fat was found to provide superior baking properties compared to lard. Margarine made from hydrogenated soybean oil began to replace butterfat. Hydrogenated fat such as Crisco and Spry, sold in England, began to replace butter and lard in the baking of bread, pies, cookies, and cakes in 1920.[26]

Production of hydrogenated fats increased steadily until the 1960s, as processed vegetable fats replaced animal fats in the US and other Western countries. At first, the argument was a financial one due to lower costs; advocates also said that the unsaturated trans fats of margarine were healthier than the saturated fats of butter.[27]

As early as 1956 there were suggestions in the scientific literature that trans fats could be a cause of the large increase in coronary artery disease but after three decades the concerns were still largely unaddressed.[27][28] In fact, by the 1980s, fats of animal origin had become one of the greatest concerns of dieticians. Activists, such as Phil Sokolof, who took out full page ads in major newspapers, attacked the use of beef tallow in McDonald's french fries and urged fast-food companies to switch to vegetable oils. The result was an almost overnight switch by most fast-food outlets to switch to trans fats.

Studies in the early 1990s, however, brought renewed scrutiny and confirmation of the negative health impact of trans fats. In 1994, it was estimated that trans fats caused 20,000 deaths annually in the US from heart disease.[29]

Mandatory food labeling for trans fats was introduced in several countries.[30] Campaigns were launched by activists to bring attention to the issue and change the practices of food manufacturers.[31] In January 2007, faced with the prospect of an outright ban on the sale of their product, Crisco was reformulated to meet the United States Food and Drug Administration definition of "zero grams trans fats per serving" (that is less than one gram per tablespoon, or up to 7% by weight; or less than 0.5 grams per serving size)[32][33][34][35] by boosting the saturation and then diluting the resulting solid fat with unsaturated vegetable oils.

A University of Guelph research group has found a way to mix oils (such as olive, soybean, and canola), water, monoglycerides, and fatty acids to form a "cooking fat" that acts the same way as trans and saturated fats.[36][37]

Chemistry

In chemical terms, trans fat is a fat (lipid) molecule that contains one or more double bonds in trans geometric configuration.

A double bond may exhibit one of two possible configurations: trans or cis. In trans configuration, the carbon chain extends from opposite sides of the double bond, whereas, in cis configuration, the carbon chain extends from the same side of the double bond. The trans molecule is a straighter molecule. The cis molecule is bent.[38]

| Trans (Elaidic acid) | Cis (Oleic acid) | Saturated (Stearic acid) |

|---|---|---|

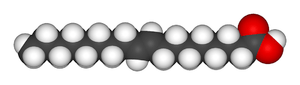

| Elaidic acid is the principal trans unsaturated fatty acid often found in partially hydrogenated vegetable oils.[39] | Oleic acid is a cis unsaturated fatty acid making up 55–80% of olive oil.[40] | Stearic acid is a saturated fatty acid found in animal fats and is the intended product in full hydrogenation. Stearic acid is neither cis nor trans because it has no carbon-carbon double bonds. |

|

|

.png) |

| |

|

|

| These fatty acids are geometric isomers (structurally identical except for the arrangement of the double bond). | This fatty acid contains no carbon-carbon double bonds and is not isomeric with the previous two. | |

A fatty acid is characterized as either saturated or unsaturated based on the presence of double bonds in its structure. If the molecule contains no double bonds, it is said to be saturated; otherwise, it is unsaturated to some degree.[41][42]

Only unsaturated fats can be trans or cis fat, since only a double bond can be locked to these orientations. Saturated fatty acids are never called trans fats because they have no double bonds. Therefore, all their bonds are freely rotatable. Other types of fatty acids, such as crepenynic acid, which contains a triple bond, are rare and of no nutritional significance.

Carbon atoms are tetravalent, forming four covalent bonds with other atoms, whereas hydrogen atoms bond with only one other atom. In saturated fatty acids, each carbon atom (besides the last) is connected to its two neighbour carbon atoms as well as two hydrogen atoms. In unsaturated fatty acids, the carbon atoms that are missing a hydrogen atom are joined by double bonds rather than single bonds so that each carbon atom participates in four bonds.

Hydrogenation of an unsaturated fatty acid refers to the addition of hydrogen atoms to the acid, causing double bonds to become single ones, as carbon atoms acquire new hydrogen partners (to maintain four bonds per carbon atom). Full hydrogenation results in a molecule containing the maximum amount of hydrogen (in other words, the conversion of an unsaturated fatty acid into a saturated one). Partial hydrogenation results in the addition of hydrogen atoms at some of the empty positions, with a corresponding reduction in the number of double bonds. Typical commercial hydrogenation is partial in order to obtain a malleable mixture of fats that is solid at room temperature, but melts upon baking (or consumption).

In most naturally occurring unsaturated fatty acids, the hydrogen atoms are on the same side of the double bonds of the carbon chain (cis configuration — from the Latin, meaning "on the same side"). However, partial hydrogenation reconfigures most of the double bonds that do not become chemically saturated, twisting them so that the hydrogen atoms end up on different sides of the chain. This type of configuration is called trans, from the Latin, meaning "across".[43] The trans configuration is the lower energy form, and is favored when catalytically equilibrated as a side reaction in hydrogenation.

The same molecule, containing the same number of atoms, with a double bond in the same location, can be either a trans or a cis fatty acid depending on the configuration of the double bond. For example, oleic acid and elaidic acid are both unsaturated fatty acids with the chemical formula C9H17C9H17O2.[44] They both have a double bond located midway along the carbon chain. It is the configuration of this bond that sets them apart. The configuration has implications for the physical-chemical properties of the molecule. The trans configuration is straighter, while the cis configuration is noticeably kinked as can be seen from the three-dimensional representation shown above.

The trans fatty acid elaidic acid has different chemical and physical properties, owing to the slightly different bond configuration. It has a much higher melting point, 45 °C, than oleic acid, 13.4 °C, due to the ability of the trans molecules to pack more tightly, forming a solid that is more difficult to break apart.[44] This notably means that it is a solid at human body temperatures.

In food production, the goal is not to simply change the configuration of double bonds while maintaining the same ratios of hydrogen to carbon. Instead, the goal is to decrease the number of double bonds and increase the amount of hydrogen in the fatty acid. This changes the consistency of the fatty acid and makes it less prone to rancidity (in which free radicals attack double bonds). Production of trans fatty acids is therefore an undesirable side effect of partial hydrogenation.

Catalytic partial hydrogenation necessarily produces trans-fats, because of the reaction mechanism. In the first reaction step, one hydrogen is added, with the other, coordinatively unsaturated, carbon being attached to the catalyst. The second step is the addition of hydrogen to the remaining carbon, producing a saturated fatty acid. The first step is reversible, such that the hydrogen is readsorbed on the catalyst and the double bond is re-formed. The intermediate with only one hydrogen added contains no double bond and can freely rotate. Thus, the double bond can re-form as either cis or trans, of which trans is favored, regardless the starting material. Complete hydrogenation also hydrogenates any produced trans fats to give saturated fats.

Researchers at the United States Department of Agriculture have investigated whether hydrogenation can be achieved without the side effect of trans fat production. They varied the pressure under which the chemical reaction was conducted — applying 1400 kPa (200 psi) of pressure to soybean oil in a 2-liter vessel while heating it to between 140 °C and 170 °C. The standard 140 kPa (20 psi) process of hydrogenation produces a product of about 40% trans fatty acid by weight, compared to about 17% using the high-pressure method. Blended with unhydrogenated liquid soybean oil, the high-pressure-processed oil produced margarine containing 5 to 6% trans fat. Based on current U.S. labeling requirements (see below), the manufacturer could claim the product was free of trans fat.[45] The level of trans fat may also be altered by modification of the temperature and the length of time during hydrogenation.

Trans fat levels may be measured. Measurement techniques include chromatography (by silver ion chromatography on thin layer chromatography plates, or small high-performance liquid chromatography columns of silica gel with bonded phenylsulfonic acid groups whose hydrogen atoms have been exchanged for silver ions). The role of silver lies in its ability to form complexes with unsaturated compounds. Gas chromatography and mid-infrared spectroscopy are other methods in use.

Presence in food

| food type | trans-fat content |

|---|---|

| shortenings | 10 to 33g |

| margarine/spreads | 0.2[47] to 26 g |

| butter | 4 g[47] |

| animal fat | 0 to 5 g[48] |

| breads/cake products | 0.1 to 10 g |

| cookies and crackers | 1 to 8 g |

| salty snacks | 0 to 4 g |

| cake frostings and sweets | 0.1 to 7g |

A type of trans fat occurs naturally in the milk and body fat of ruminants (such as cattle and sheep) at a level of 2–5% of total fat.[48] Natural trans fats, which include conjugated linoleic acid (CLA) and vaccenic acid, originate in the rumen of these animals. CLA has two double bonds, one in the cis configuration and one in trans, which makes it simultaneously a cis- and a trans-fatty acid.

Animal-based fats were once the only trans fats consumed, but by far the largest amount of trans fat consumed today is created by the processed food industry as a side effect of partially hydrogenating unsaturated plant fats (generally vegetable oils). These partially hydrogenated fats have displaced natural solid fats and liquid oils in many areas, the most notable ones being in the fast food, snack food, fried food, and baked goods industries.[49]

Partially hydrogenated oils have been used in food for many reasons. Hydrogenation increases product shelf life and decreases refrigeration requirements. Many baked foods require semi-solid fats to suspend solids at room temperature; partially hydrogenated oils have the right consistency to replace animal fats such as butter and lard at lower cost. They are also an inexpensive alternative to other semi-solid oils such as palm oil.

Up to 45% of the total fat in those foods containing artificial trans fats formed by partially hydrogenating plant fats may be trans fat.[48] Baking shortenings, unless reformulated, contain around 30% trans fats compared to their total fats. High-fat dairy products such as butter contain about 4%. Margarines not reformulated to reduce trans fats may contain up to 15% trans fat by weight,[50] but some reformulated ones are less than 1% trans fat.

It has been established that trans fats in human milk fluctuate with maternal consumption of trans fat, and that the amount of trans fats in the bloodstream of breastfed infants fluctuates with the amounts found in their milk. In 1999, reported percentages of trans fats (compared to total fats) in human milk ranged from 1% in Spain, 2% in France, 4% in Germany, and 7% in Canada and the United States.[51]

Trans fats are used in shortenings for deep-frying in restaurants, as they can be used for longer than most conventional oils before becoming rancid. In the early 21st century, non-hydrogenated vegetable oils that have lifespans exceeding that of the frying shortenings became available.[52] As fast-food chains routinely use different fats in different locations, trans fat levels in fast food can have large variations. For example, an analysis of samples of McDonald's French fries collected in 2004 and 2005 found that fries served in New York City contained twice as much trans fat as in Hungary, and 28 times as much as in Denmark (where trans fats are restricted). At KFC, the pattern was reversed with Hungary's product containing twice the trans fat of the New York product. Even within the US there was variation, with fries in New York containing 30% more trans fat than those from Atlanta.[53]

Nutritional guidelines

The National Academy of Sciences (NAS) advises the United States and Canadian governments on nutritional science for use in public policy and product labeling programs. Their 2002 Dietary Reference Intakes for Energy, Carbohydrate, Fiber, Fat, Fatty Acids, Cholesterol, Protein, and Amino Acids[54] contains their findings and recommendations regarding consumption of trans fat (summary).

Their recommendations are based on two key facts. First, "trans fatty acids are not essential and provide no known benefit to human health",[5] whether of animal or plant origin.[55] Second, while both saturated and trans fats increase levels of LDL, trans fats also lower levels of HDL;[6] thus increasing the risk of coronary heart disease. The NAS is concerned "that dietary trans fatty acids are more deleterious with respect to coronary heart disease than saturated fatty acids".[6] This analysis is supported by a 2006 New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM) scientific review that states "from a nutritional standpoint, the consumption of trans fatty acids results in considerable potential harm but no apparent benefit."[56]

Because of these facts and concerns, the NAS has concluded there is no safe level of trans fat consumption. There is no adequate level, recommended daily amount or tolerable upper limit for trans fats. This is because any incremental increase in trans fat intake increases the risk of coronary heart disease.[6]

Despite this concern, the NAS dietary recommendations have not recommended the elimination of trans fat from the diet. This is because trans fat is naturally present in many animal foods in trace quantities, and therefore its removal from ordinary diets might introduce undesirable side effects and nutritional imbalances if proper nutritional planning is not undertaken. The NAS has, therefore, "recommended that trans fatty acid consumption be as low as possible while consuming a nutritionally adequate diet".[57] Like the NAS, the World Health Organization has tried to balance public health goals with a practical level of trans fat consumption, recommending in 2003 that trans fats be limited to less than 1% of overall energy intake.[48]

The US National Dairy Council has asserted that the trans fats present in animal foods are of a different type than those in partially hydrogenated oils, and do not appear to exhibit the same negative effects.[58] While a recent scientific review agrees with the conclusion (stating that "the sum of the current evidence suggests that the Public health implications of consuming trans fats from ruminant products are relatively limited"), it cautions that this may be due to the low consumption of trans fats from animal sources compared to artificial ones.[56]

More recent inquiry (independent of the dairy industry) has found in a 2008 Dutch meta-analysis that all trans fats, regardless of natural or artificial origin equally raise LDL and lower HDL levels.[59] Other studies though have shown different results when it comes to animal based trans fats like conjugated linoleic acid (CLA). Although CLA is known for its anticancer properties, researchers have also found that the cis-9, trans-11 form of CLA can reduce the risk for cardiovascular disease and help fight inflammation.[60][61]

Health risks

Partially hydrogenated vegetable oils have been an increasingly significant part of the human diet for about 100 years (in particular, since the later half of the 20th century and where more processed foods are consumed),[62] and some deleterious effects of trans fat consumption are scientifically accepted, forming the basis of the health guidelines discussed above.

The exact biochemical methods by which trans fats produce specific health problems are a topic of continuing research. One theory is that the human lipase enzyme works only on the cis configuration and cannot metabolize a trans fat although this theory has been overturned by the recognition that trans fat is metabolized but competitively inhibits the metabolism of other fatty acids.[63] Intake of dietary trans fat perturbs the body's ability to metabolize essential fatty acids (EFAs including Omega 3) leading to changes in the phospholipid fatty acid composition in the aorta, the main artery of the heart, thereby increasing risk of coronary heart disease.[64] While the mechanisms through which trans fats contribute to coronary heart disease are fairly well understood, the mechanism for trans fat's effect on diabetes is still under investigation. Trans fatty acids may impair the metabolism of long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids (LCPUFAs),[65] but maternal pregnancy trans fatty acid intake has been inversely associated with LCPUFAs levels in infants at birth thought to underlie the positive association between breastfeeding and intelligence.[66]

High intake of trans fatty acids can lead to many health problems throughout one's life.[67] Trans fat is abundant in fast food restaurants.[62] It is consumed in greater quantities by people who do not have access to a diet consisting of fewer hydrogenated fats, or who often consume fast food. A diet high in trans fats can contribute to obesity, high blood pressure, and a greater risk for heart disease. Trans fat has also been implicated in the development of Type 2 diabetes.[68]

Coronary heart disease

The primary health risk identified for trans fat consumption is an elevated risk of coronary heart disease (CHD).[69] A 1994 study estimated that over 30,000 cardiac deaths per year in the United States are attributable to the consumption of trans fats.[29] By 2006 upper estimates of 100,000 deaths were suggested.[70] A comprehensive review of studies of trans fats published in 2006 in the New England Journal of Medicine reports a strong and reliable connection between trans fat consumption and CHD, concluding that "On a per-calorie basis, trans fats appear to increase the risk of CHD more than any other macronutrient, conferring a substantially increased risk at low levels of consumption (1 to 3% of total energy intake)".[56][71]

The major evidence for the effect of trans fat on CHD comes from the Nurses' Health Study — a cohort study that has been following 120,000 female nurses since its inception in 1976. In this study, Hu and colleagues analyzed data from 900 coronary events from the study's population during 14 years of followup. He determined that a nurse's CHD risk roughly doubled (relative risk of 1.93, CI: 1.43 to 2.61) for each 2% increase in trans fat calories consumed (instead of carbohydrate calories). By contrast, for each 5% increase in saturated fat calories (instead of carbohydrate calories) there was a 17% increase in risk (relative risk of 1.17, CI: 0.97 to 1.41). "The replacement of saturated fat or trans unsaturated fat by cis (unhydrogenated) unsaturated fats was associated with larger reductions in risk than an isocaloric replacement by carbohydrates."[72] Hu also reports on the benefits of reducing trans fat consumption. Replacing 2% of food energy from trans fat with non-trans unsaturated fats more than halves the risk of CHD (53%). By comparison, replacing a larger 5% of food energy from saturated fat with non-trans unsaturated fats reduces the risk of CHD by 43%.[72]

Another study considered deaths due to CHD, with consumption of trans fats being linked to an increase in mortality, and consumption of polyunsaturated fats being linked to a decrease in mortality.[69][73]

There are two accepted tests that measure an individual's risk for coronary heart disease, both blood tests. The first considers ratios of two types of cholesterol, the other the amount of a cell-signalling cytokine called C-reactive protein. The ratio test is more accepted, while the cytokine test may be more powerful but is still being studied.[69] The effect of trans fat consumption has been documented on each as follows:

- Cholesterol ratio: This ratio compares the levels of LDL to HDL. Trans fat behaves like saturated fat by raising the level of LDL, but, unlike saturated fat, it has the additional effect of decreasing levels of HDL. The net increase in LDL/HDL ratio with trans fat is approximately double that due to saturated fat.[74][75][76] (Higher ratios are worse.) One randomized crossover study published in 2003 comparing the effect of eating a meal on blood lipids of (relatively) cis and trans fat rich meals showed that cholesteryl ester transfer (CET) was 28% higher after the trans meal than after the cis meal and that lipoprotein concentrations were enriched in apolipoprotein(a) after the trans meals.[77]

- C-reactive protein (CRP): A study of over 700 nurses showed that those in the highest quartile of trans fat consumption had blood levels of CRP that were 73% higher than those in the lowest quartile.[78]

Other health risks

There are suggestions that the negative consequences of trans fat consumption go beyond the cardiovascular risk. In general, there is much less scientific consensus asserting that eating trans fat specifically increases the risk of other chronic health problems:

- Alzheimer's Disease: A study published in Archives of Neurology in February 2003 suggested that the intake of both trans fats and saturated fats promote the development of Alzheimer disease,[79] although not confirmed in an animal model.[80] It has been found that trans fats impaired memory and learning in middle-age rats. The trans-fat eating rats' brains had fewer proteins critical to healthy neurological function. Inflammation in and around the hippocampus, the part of the brain responsible for learning and memory. These are the exact types of changes normally seen at the onset of Alzheimer's, but seen after six weeks, even though the rats were still young.[81]

- Cancer: There is no scientific consensus that consumption of trans fats significantly increases cancer risks across the board.[69] The American Cancer Society states that a relationship between trans fats and cancer "has not been determined."[82] One study has found a positive connection between trans fat and prostate cancer.[83] However, a larger study found a correlation between trans fats and a significant decrease in high-grade prostate cancer.[84] An increased intake of trans fatty acids may raise the risk of breast cancer by 75%, suggest the results from the French part of the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition.[85][86]

- Diabetes: There is a growing concern that the risk of type 2 diabetes increases with trans fat consumption.[69] However, consensus has not been reached.[56] For example, one study found that risk is higher for those in the highest quartile of trans fat consumption.[87] Another study has found no diabetes risk once other factors such as total fat intake and BMI were accounted for.[88]

- Obesity: Research indicates that trans fat may increase weight gain and abdominal fat, despite a similar caloric intake.[89] A 6-year experiment revealed that monkeys fed a trans fat diet gained 7.2% of their body weight, as compared to 1.8% for monkeys on a mono-unsaturated fat diet.[90][91] Although obesity is frequently linked to trans fat in the popular media,[92] this is generally in the context of eating too many calories; there is not a strong scientific consensus connecting trans fat and obesity, although the 6-year experiment did find such a link, concluding that "under controlled feeding conditions, long-term TFA consumption was an independent factor in weight gain. TFAs enhanced intra-abdominal deposition of fat, even in the absence of caloric excess, and were associated with insulin resistance, with evidence that there is impaired post-insulin receptor binding signal transduction."[91]

- Liver dysfunction: Trans fats are metabolized differently by the liver than other fats and interfere with delta 6 desaturase. Delta 6 desaturase is an enzyme involved in converting essential fatty acids to arachidonic acid and prostaglandins, both of which are important to the functioning of cells.[93]

- Infertility in women: One 2007 study found, "Each 2% increase in the intake of energy from trans unsaturated fats, as opposed to that from carbohydrates, was associated with a 73% greater risk of ovulatory infertility...".[94]

- Major depressive disorder: Spanish researchers analysed the diets of 12,059 people over six years and found those who ate the most trans fats had a 48 per cent higher risk of depression than those who did not eat trans fats.[95] One mechanism may be trans-fats' substitution for docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) levels in the orbitofrontal cortex (OFC). Very high intake of trans-fatty acids (43% of total fat) in mice from 2 to 16 months of age was associated with lowered DHA levels in the brain (p=0.001).[80] When the brains of 15 major depressive subjects who had committed suicide were examined post-mortem and compared against 27 age-matched controls, the suicidal brains were found to have 16% less (male average) to 32% less (female average) DHA in the OFC. The OFC controls reward, reward expectation, and empathy (all of which are reduced in depressive mood disorders) and regulates the limbic system.[96]

- Behavioral irritability and aggression: a 2012 observational analysis of subjects of an earlier study found a strong relation between dietary trans fat acids and self-reported behavioral aggression and irritability, suggesting but not establishing causality.[97]

- Diminished memory: In a 2015 article, researchers re-analyzing results from the 1999-2005 UCSD Statin Study argue that "greater dietary trans fatty acid consumption is linked to worse word memory in adults during years of high productivity, adults age <45".[98]

Public response and regulation

International

The international trade in food is standardized in the Codex Alimentarius. Hydrogenated oils and fats come under the scope of Codex Stan 19.[99] Non-dairy fat spreads are covered by Codex Stan 256-2007.[100] In the Codex Alimentarius, trans fat to be labelled as such is defined as the geometrical isomers of monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fatty acids having non-conjugated [interrupted by at least one methylene group (−CH2−)] carbon-carbon double bonds in the trans configuration. This definition excludes specifically the trans fats (vaccenic acid and conjugated linoleic acid) that are present especially in human milk, dairy products, and beef.

Argentina

Since August 2006 food products should be labelled with the amount of trans fat in them.[101] Since 2010 vegetable oils and fats directly sold to consumers must only contain 2% of trans fat over total fat, and other food must contain less than 5% of their total fat.[102] Starting on 10 December 2014, Argentina has on effect a total ban on food with trans fat, a move that could save the government more than US$100 million a year on healthcare.[103]

Australia

The Australian federal government has indicated that it wants to pursue actively a policy of reducing trans fats from fast foods. The former federal assistant health minister, Christopher Pyne, asked fast food outlets to reduce their trans fat usage. A draft plan was proposed, with a September 2007 timetable, in order to reduce reliance on trans fats and saturated fats.[104]

Currently, Australia's food labeling laws do not require trans fats to be shown separately from the total fat content. However, margarine in Australia has been mostly free of trans fat since 1996.[105]

Austria

Trans fat content limited to 4% of total fat, 2% on products that contain more than 20% fat.[106]

Brazil

Resolution 360 of 23 December 2003 by the Brazilian ministry of health required for the first time in the country that the amount of trans fat to be specified in labels of food products. On 31 July 2006, such labelling of trans fat contents became mandatory. In 2007 the ministry established a target to reduce the total amount of trans fat in any industrialized food sold in Brazil to a maximum of 2% by the end of 2010.

Canada

In November 2004, an opposition day motion seeking a ban similar to Denmark's was introduced by Jack Layton of the New Democratic Party, and passed through the House of Commons by an overwhelming 193–73 vote.[107] Like all Commons motions, it served as an expression of the views of the House but was not binding on the government and has no force under the law.

Since December 2005, Health Canada has required that food labels list the amount of trans fat in the nutrition facts section for most foods. Products with less than 0.2 grams of trans fat per serving may be labeled as free of trans fats.[108] These labelling allowances are not widely known, but as an awareness of them develops, controversy over truthful labelling is growing. In Canada, trans fat quantities on labels include naturally occurring trans fats from animal sources.[109]

In June 2006, a task force co-chaired by Health Canada and the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada recommended a limit of 5% trans fat (of total fat) in all products sold to consumers in Canada (2% for tub margarines and spreads).[48] The amount was selected such that "most of the industrially produced trans fats would be removed from the Canadian diet, and about half of the remaining trans fat intake would be of naturally occurring trans fats". This recommendation has been endorsed by the Canadian Restaurant and Foodservices Association[110] and Food & Consumer Products of Canada has congratulated the task force on the report,[111] although it did not recommend delaying implementation to 2010 as they had previously advocated.[112]

Ten months after submitting their report the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada and Toronto Public Health issued a plea to the government of Canada: "to act immediately on the task force's recommendations and to eliminate harmful trans fat from Canada's food supply."[113]

On 20 June 2007, the federal government announced its intention to regulate trans fats to the June 2006 standard unless the food industry voluntarily complied with these limits within two years.[114][115]

On 1 January 2008, Calgary became the first city in Canada to reduce trans fats from restaurants and fast food chains. Trans fats present in cooking oils may not exceed 2% of the total fat content.[116] However, the replacement of local health regions with the Alberta Health Services Board in 2009 has temporarily eliminated all enforcement of the law.[117]

Effective 30 September 2009, British Columbia became the first province in Canada to mandate the June 2006 recommendation in provincially regulated food services establishments.[118][119]

Public perception

A cross-sectional study was conducted in Regina, Saskatchewan in February 2009 at 3 different grocery stores located in 3 different regions that had the same median income before taxes of around $30,000. Of the 211 respondents to the study, most were women who purchased most of the food for their household. When asked how they decide what food to buy, the most important factors were price, nutritional value, and need. When looking at the nutritional facts, however, they indicated that they looked at the ingredients, and neglected to pay attention to the amount of trans fat. This means that trans fat is not on their minds unless they are specifically told of it. When asked if they ever heard about trans fat, 98% said, "Yes." However, only 27% said that it was unhealthy. Also, 79% said that they only knew a little about trans fats, and could have been more educated. Respondents aged 41–60 were more likely to view trans fat as a major health concern, compared to ages 18–40. When asked if they would stop buying their favorite snacks if they knew it contained trans fat, most said they would continue purchasing it, especially the younger respondents. Also, of the respondents that called trans fat a major concern, 56% of them still wouldn't change their diet to non-trans fat snacks. This is because taste and food gratification take precedence over perceived risk to health. "The consumption of trans fats and the associated increased risk of CHD is a public health concern regardless of age and socioeconomic status".[120]

Denmark

Denmark became the first country to introduce laws strictly regulating the sale of many foods containing trans fats[121] in March 2003, a move that effectively bans partially hydrogenated oils. The limit is 2% of fats and oils destined for human consumption. This restriction is on the ingredients rather than the final products. This regulatory approach has made Denmark the only country in which it is possible to eat "far less" than 1 g of industrially produced trans fats daily, even with a diet including prepared foods.[122] It is hypothesized that the Danish government's efforts to decrease trans fat intake from 6 g to 1 g per day over 20 years is related to a 50% decrease in deaths from ischemic heart disease.[123]

Greece

Law in Greece limits content of trans fats sold in school cantines to 0.1% (Ministerial Decision Υ1γ/ΓΠ/οικ 81025/ΦΕΚ 2135/τ.Β’/29-08-2013 as modified by Ministerial Decision Υ1γ/ Γ.Π/οικ 96605/ΦΕΚ 2800 τ.Β/4-11-201).[124]

Iceland

Total trans fat content was limited in 2010 to 2% of total fat content.[125][126]

Israel

Since 2014, It is obligatory to mark food products with more than 2% (by weight) fat. The nutritional facts must contain the amount of trans fats.[127]

Sweden

Parliament has given the government a mandate in 2011 to submit without delay a law prohibiting the use of industrially produced trans fats in foods.[128]

Switzerland

Switzerland followed Denmark's trans fats ban, and implemented its own beginning in April 2008.[129]

European Union

In 2004, the European Food Safety Authority produced a scientific opinion on trans fatty acids, surmising that "higher intakes of TFA may increase risk for coronary heart disease".[130]

In Belgium, the Conseil Supérieur de la Santé has published in 2012 a science-policy advisory report on industrially produced trans fatty acids that focuses on the general population. It also provides specific information and recommendations regarding the nutritional requirements for dietary fats as well as amendments to the food legislation. The council recommends to Belgian authorities a contraignant legislation for the interdiction of more than 2 g of trans fatty acids / 100 g of fat in food products. Unfortunately, since this report there is no action in this way by legislatives authorities.[131]

United Kingdom

In October 2005, the Food Standards Agency (FSA) asked for better labelling in the UK.[132] In the edition of 29 July 2006 of the British Medical Journal, an editorial also called for better labelling.[133] In January 2007, the British Retail Consortium announced that major UK retailers, including Asda, Boots, Co-op, Iceland, Marks and Spencer, Sainsbury's, Tesco and Waitrose intended to cease adding trans fatty acids to their own products by the end of 2007.[134]

Sainsbury's became the first UK major retailer to ban all trans fat from all their own brand foods.

On 13 December 2007, the Food Standards Agency issued news releases stating that voluntary measures to reduce trans fats in food had already resulted in safe levels of consumer intake.[135][136]

On 15 April 2010, a British Medical Journal editorial called for trans fats to be "virtually eliminated in the United Kingdom by next year".[137]

The June 2010 National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) report Prevention of cardiovascular disease declared that 40,000 cardiovascular disease deaths in 2006 were "mostly preventable".[138] To achieve this, NICE offered 24 recommendations including product labelling, public education, protecting under–16s from marketing of unhealthy foods, promoting exercise and physically active travel, and even reforming the Common Agricultural Policy to reduce production of unhealthy foods. Fast-food outlets were mentioned as a risk factor, with (in 2007) 170 g of McDonald's fries and 160 g nuggets containing 6 to 8 g of trans fats, conferring a substantially increased risk of coronary heart disease death.[139] NICE made three specific recommendation for diet: (1) reduction of dietary salt to 3 g per day by 2025; (2) halving consumption of saturated fats; and (3) eliminating the use of industrially produced trans fatty acids in food. However, the recommendations were greeted unhappily by the food industry, which stated that it was already voluntarily dropping the trans fat levels to below the WHO recommendations of a maximum of 2%.

Rejecting an outright ban, the Health Secretary Andrew Lansley launched on 15 March 2012 a voluntary pledge to remove artificial trans fats by the end of the year. Asda, Pizza Hut, Burger King, Tesco, Unilever and United Biscuits are some of 73 businesses who have agreed to do so. Lansley and his special Adviser Bill Morgan previously worked for firms with interests in the food industry and some journalists have alleged that this results in a conflict of interest.[140] Many health professionals are not happy with the voluntary nature of the deal. Simon Capewell, Professor of Clinical Epidemiology at the University of Liverpool, felt that justifying intake on the basis of average figures was unsuitable since some members of the community could considerably exceed this.[141]

United States

Before 2006, consumers in the United States could not directly determine the presence (or quantity) of trans fats in food products. This information could only be inferred from the ingredient list, notably from the partially hydrogenated ingredients. In 2010, according to the FDA, the average American consumed 5.8 grams of trans fat per day (2.6% of energy intake).[142] Monoglycerides and diglycerides are not considered fats by the FDA, despite their nearly equal calorie per weight contribution during actual ingestion.[143] Critically important is the apparent fact that trans fatty acids that are part of mono- and diglycerides are not required to be listed on the ingredients label as making contributions to calorie count or trans fatty acid content.

On 11 July 2003, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued a regulation requiring manufacturers to list trans fat on the Nutrition Facts panel of foods and some dietary supplements.[32][33] The new labeling rule became mandatory across the board, even for companies that petitioned for extensions, on 1 January 2008. However, unlike in many other countries, trans fat levels of less than 0.5 grams per serving can be listed as 0 grams trans fat on the food label.[144] According to a study published in the Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, without an interpretive footnote or further information on recommended daily value, many consumers do not know how to interpret the meaning of trans fat content on the Nutrition Facts panel. In fact, without specific prior knowledge about trans fat and its negative health effects, consumers, including those at risk for heart disease, may misinterpret nutrient information provided on the panel.[34] The FDA did not approve nutrient content claims such as "trans fat free" or "low trans fat", as they could not determine a "recommended daily value". Nevertheless, the agency is planning a consumer study to evaluate the consumer understanding of such claims and perhaps consider a regulation allowing their use on packaged foods.[145] However, there is no requirement to list trans fats on institutional food packaging; thus bulk purchasers such as schools, hospitals, jails and cafeterias are unable to evaluate the trans fat content of commercial food items.[146] The FDA defines trans fats as containing one or more trans linkage that are not in a conjugated system. This is an important distinction, as it distinguishes non-conjugated synthetic trans fats from naturally occurring fatty acids with conjugated trans double bonds, such as conjugated linoleic acid.

Critics of the plan, including FDA advisor Dr. Carlos Camargo, have expressed concern that the 0.5 gram per serving threshold is too high to refer to a food as free of trans fat. This is because a person eating many servings of a product, or eating multiple products over the course of the day may still consume a significant amount of trans fat.[35] Despite this, the FDA estimates that by 2009, trans fat labeling will have prevented from 600 to 1,200 cases of coronary heart disease and 250 to 500 deaths each year. This benefit is expected to result from consumers choosing alternative foods lower in trans fats as well as manufacturers reducing the amount of trans fats in their products.

The American Medical Association supports any state and federal efforts to ban the use of artificial trans fats in U.S. restaurants and bakeries.[147]

The American Public Health Association adopted a new policy statement regarding trans fats in 2007. These new guidelines, entitled Restricting Trans Fatty Acids in the Food Supply, recommend that the government require nutrition facts labeling of trans fats on all commercial food products. They also urge federal, state, and local governments to ban and monitor use of trans fats in restaurants. Furthermore, the APHA recommends barring the sales and availability of foods containing significant amounts of trans fat in public facilities including universities, prisons, and day care facilities etc.[146]

On 7 November 2013, the FDA issued a preliminary determination that trans fats are not "generally recognized as safe", which was widely seen as a precursor to a reclassification of trans fats as a "food additive," meaning they could not be used in foods without specific regulatory authorization. This would have the effect of virtually eliminating trans fats from the US food supply.[148][149] The ruling was formally enacted on 16 June 2015, requiring that within three years, all food prepared in the United States must not include trans fats, unless approved by the FDA.[150]

State and local regulation in the United States

The state of California and some US cities are acting to reduce consumption of trans fats. In May 2005, Tiburon, California, became the first American city wherein all restaurants voluntarily cook with trans fat-free oils.[151] Montgomery County, Maryland approved a ban on partially hydrogenated oils, becoming the first county in the nation to restrict trans fats.[152]

New York City embarked on a campaign in 2005 to reduce consumption of trans fats, noting that heart disease is the primary cause of resident deaths. This has included a Public education campaign (see trans fat pamphlet) and a request to restaurant owners to eliminate trans fat from their offerings voluntarily.[153] Finding that the voluntary program was not successful, New York City's Board of Health in 2006 solicited public comments on a proposal to ban artificial trans fats in restaurants.[154] The board voted to ban trans fat in restaurant food on 5 December 2006. New York was the first large US city to strictly limit trans fats in restaurants. Restaurants were barred from using most frying and spreading fats containing artificial trans fats above 0.5 g per serving on 1 July 2007, and were supposed to have met the same target in all of their foods by 1 July 2008.[155]

The Philadelphia City Council voted unanimously to pass a ban on 8 February 2007, which was signed into law on 15 February 2007, by Mayor John F. Street.[156][157] By 1 September 2007, eateries must cease frying food in trans fats. A year later, trans fat must not be used as an ingredient in commercial kitchens. The law does not apply to prepackaged foods sold in the city. On 10 October 2007, the Philadelphia City Council approved the use of trans fats by small bakeries throughout the city.[158]

Nassau County, a suburban county on Long Island, New York, banned trans fats in restaurants effective 1 April 2008. Bakeries were granted an extension until 1 April 2011.

Albany County of New York passed a ban on trans fats. The ban was adopted after a unanimous vote by the county legislature on 14 May 2007. The decision was made after New York City's decision, but no plan has been put into place. Legislators received a letter from Rick J. Sampson, president and CEO of the New York State Restaurant Association, calling on them to "delay any action on this issue until the full impact of the New York City ban is known."

San Francisco officially asked its restaurants to stop using trans fat in January 2008. The voluntary program will grant a city decal to restaurants that comply and apply for the decal.[159] Legislators say the next step will be a mandatory ban.

Chicago also considered a ban on oils containing trans fats for large chain restaurants, and finally settled on a partial ban on oils and posting requirements for fast food restaurants.[160][161]

On 19 December 2006, Massachusetts state representative Peter Koutoujian filed the first state level legislation that would ban restaurants from preparing foods with trans fats.[162] The statewide legislation has not yet passed. However, the city of Boston did ban the sale of foods containing artificial trans fats at more than 0.5 grams per serving, which is similar to the New York City regulation; there are some exceptions for clearly labeled packaged foods and charitable bake sales.[163]

Maryland and Vermont were considering statewide bans of trans fats as of March 2007.[164][165]

King County, Washington passed a ban on artificial trans fats effective 1 February 2009.[166]

On 25 July 2008, California became the first state to ban trans fats in restaurants effective 1 January 2010.[167] California restaurants are prohibited from using oil, shortening, and margarine containing artificial trans fats in spreads or for frying, with the exception of deep frying doughnuts.[167][168][169] As of 1 January 2011, doughnuts and other baked goods have been prohibited from containing artificial trans fats.[167][168][169] Packaged foods are not covered by the ban and can legally contain trans fats.[170]

In 2007, the American Heart Association launched its "Face the Fats" campaign to help educate the public about the negative effects of trans fats, and bring it into the large picture.

2015–2018 phaseout

In 2013, the FDA planned to phase out the use of trans fats in all foods, considering that there is no safe amount of trans fats that should be consumed.[171]

17 June 2015, the FDA issued a final determination that there is no consensus that industrially-produced trans fatty acids are generally recognized as safe for any use in human food. Trans fat must be removed from prepared foods within three years by June 2018.[172] The FDA estimates the ban will cost the food industry $6.2 billion over 20 years as the industry reformulates products and substitutes new ingredients for trans fat. The benefits are estimated at $140 billion over 20 years mainly from lower health care spending. Food companies can petition the FDA for approval of specific uses of partially hydrogenated oils if the companies submit data proving the oils' use is safe.[173]

Food industry response

Manufacturer response

Palm oil, a natural oil extracted from the fruit of oil palm trees that is semi-solid at room temperature (15–25 degrees Celsius), is increasingly being used as an alternative to partially hydrogenated fats in baking and processed food applications.[174][175] However, a 2006 study supported by the National Institutes of Health and the USDA Agricultural Research Service concluded that palm oil is not a safe substitute for partially hydrogenated fats (trans fats) in the food industry, because palm oil results in adverse changes in the blood concentrations of LDL and apolipoprotein B just as trans fat does.[176][177]

In May 2003, BanTransFats.com Inc., a U.S. non-profit corporation, filed a lawsuit against the food manufacturer Kraft Foods in an attempt to force Kraft to remove trans fats from the Oreo cookie. The lawsuit was withdrawn when Kraft agreed to work on ways to find a substitute for the trans fat in the Oreo.

The J.M. Smucker Company, American manufacturer of Crisco (the original partially hydrogenated vegetable shortening), in 2004 released a new formulation made from solid saturated palm oil cut with soybean oil and sunflower oil. This blend yielded an equivalent shortening much like the previous partially hydrogenated Crisco, and was labelled zero grams of trans fat per 1 tablespoon serving (as compared with 1.5 grams per tablespoon of original Crisco).[178] As of 24 January 2007, Smucker claims that all Crisco shortening products in the US have been reformulated to contain less than one gram of trans fat per serving while keeping saturated fat content less than butter.[179] The separately marketed trans fat free version introduced in 2004 was discontinued.

On 22 May 2004, Unilever, the corporate descendant of Joseph Crosfield & Sons (the original producer of Wilhelm Normann's hydrogenation hardened oils) announced that they have eliminated trans fats from all their margarine products in Canada, including their flagship Becel brand.[180]

Agribusiness giant Bunge Limited, through their Bunge Oils division, are now producing and marketing an NT product line of non-hydrogenated oils, margarines and shortenings, made from corn, canola, and soy oils.[181]

Since 2003,[182] Loders Croklaan, a wholly owned subsidiary of Malaysia's IOI Group has been providing trans fat free bakery and confectionery fats, made from palm oil, for giant food companies in the United States to make margarine.[183]

Major users' response

Some major food chains have chosen to remove or reduce trans fats in their products. In some cases these changes have been voluntary. In other cases, however, food vendors have been targeted by legal action that has generated a lot of media attention.

Major fast food chain menus and product lines with significant artificial trans fat include Popeyes[184] [185]

The following major fast food chain menus and product lines are artificial trans fat free (that is, < 0.5 g/serving) : Taco Bell, Chick-fil-A, Girl Scout Cookies, KFC (eliminated from all but Mac and cheese, biscuits and chicken potpie in '07), the rest in '09[186] ), McDonald's, Burger King and Wendy's have greatly reduced PHOs in their food; most of the remaining trans fat is naturally occurring, in the form of about a gram per 1/4 lb. burger patty, and smaller amounts in fatty dairy products such as cheese, butter and cream. Naturally occurring trans fat causes the Baconator, for example, to have 2.5 grams; each 1/4 lb.* hamburger patty has a gram. A large chain's large fries typically had about 6 grams until around 2007.[187][188][189][190][191][192][193][194][195]

These reformulations can be partially attributed to '06 Center for Science in the Public Interest class action complaints, and to New York's trans fat ban, with companies such as McDonalds's stating they would not be selling a unique product just for New York customers but would implement a nationwide or worldwide change.[196][197]

Although IHOP restaurants pledged in a 2007 press release to eliminate transfat from their food,[198] the nutrition information on the company website for the Summer/Fall 2015 Core Menu shows that they still have a considerable amount of trans fat in their food, including 4.5 grams in their "mega monster cheeseburger".[199]

The Girl Scouts of the USA announced in November 2006 that all of their cookies contain less than 0.5 g trans fats per serving, thus meeting or exceeding the FDA guidelines for the "zero trans fat" designation.[200] High levels of trans fats remain common in packaged baked goods.[184]

Health Canada's monitoring program, which tracks the changing amounts of TFA and SFA in fast and prepared foods shows considerable progress in TFA reduction by some industrial users while others, as of 2007, lag behind. In many cases, SFAs have been substituted for the TFAs.[201][202]

See also

References

- 1 2 "About Trans Fat and Partially Hydrogenated Oils" (PDF). Center for Science in the Public Interest.

- 1 2 3 "Tentative Determination Regarding Partially Hydrogenated Oils". Federal Register. 8 November 2013. 2013-26854, Vol. 78, No. 217. Archived from the original on 6 April 2014. Retrieved 8 November 2013.

- ↑ "Mar 8 2014 FDA filing by HARVARD SCHOOL OF PUBLIC HEALTH – on the Tentative Determination Regarding Partially Hydrogenated Oils; Request for Comments and for Scientific Data and Information". regulations.gov.

- ↑ Martin, C. A.; Milinsk, M. C.; Visentainer, J. V.; Matsushita, M.; De-Souza, N. E. (2007). "Trans fatty acid-forming processes in foods: A review". Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciencias. 79 (2): 343–350. doi:10.1590/S0001-37652007000200015. PMID 17625687.

- 1 2 Food and nutrition board, institute of medicine of the national academies (2005). Dietary reference intakes for energy, carbohydrate, fiber, fat, fatty acids, cholesterol, protein, and amino acids (macronutrients). National Academies Press. p. 423.

- 1 2 3 4 Food and nutrition board, institute of medicine of the national academies (2005). Dietary reference intakes for energy, carbohydrate, fiber, fat, fatty acids, cholesterol, protein, and amino acids (macronutrients). National Academies Press. p. 504.

- ↑ "Trans fat: Avoid this cholesterol double whammy". Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research (MFMER). Retrieved 10 December 2007.

- ↑ Trans Fats From Ruminant Animals May Be Beneficial – Health News. redOrbit (8 September 2011). Retrieved 22 January 2013.

- 1 2 Bassett, C. M. C.; Edel, A. L.; Patenaude, A. F.; McCullough, R. S.; Blackwood, D. P.; Chouinard, P. Y.; Paquin, P.; Lamarche, B.; Pierce, G. N. (Jan 2010). "Dietary Vaccenic Acid Has Antiatherogenic Effects in LDLr-/- Mice". The Journal of Nutrition. 140 (1): 18–24. doi:10.3945/jn.109.105163. PMID 19923390.

- ↑ Wang, Flora & Proctor, Spencer (2 April 2008). "Natural trans fats have health benefits, University of Alberta study shows" (Press release). University of Alberta.

- ↑ Wang Y, Jacome-Sosa MM, Vine DF, Proctor SD (20 May 2010). "Beneficial effects of vaccenic acid on postprandial lipid metabolism and dyslipidemia: Impact of natural trans-fats to improve CVD risk". Lipid Technology. 22 (5): 103–106. doi:10.1002/lite.201000016.

- ↑ Bassett C, Edel AL, Patenaude AF, McCullough RS, Blackwood DP, Chouinard PY, Paquin P, Lamarche B, Pierce GN (2010). "Dietary Vaccenic Acid Has Antiatherogenic Effects in LDLr−/− Mice". The Journal of Nutrition. 140 (1): 18–24. doi:10.3945/jn.109.105163. PMID 19923390.

- ↑ David J. Baer, PhD. US Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, Beltsville Human Nutrition Research Laboratory. New Findings on Dairy Trans Fat and Heart Disease Risk, IDF World Dairy Summit 2010, 8–11 November 2010. Auckland, New Zealand

- ↑ EFSA Panel on Dietetic Products, Nutrition, and Allergies (NDA) (2010). "Scientific opinion on dietary reference values for fats". EFSA Journal. 8 (3): 1461. doi:10.2903/j.efsa.2010.1461.

- ↑ UK Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition (2007). "Update on trans fatty acids and health, Position Statement" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 January 2011.

- ↑ Brouwer IA, Wanders AJ, Katan MB (2010). "Effect of animal and industrial trans fatty acids on HDL and LDL cholesterol levels in humans – a quantitative review". PLoS ONE. 5 (3): e9434. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0009434. PMC 2830458

. PMID 20209147.

. PMID 20209147. - ↑ "Trans fat". It's your health. Health Canada. Dec 2007. Archived from the original on 20 April 2012.

- ↑ "EFSA sets European dietary reference values for nutrient intakes" (Press release). European Food Safety Authority. 26 March 2010.

- ↑ "The FDA takes step to remove artificial trans fats in processed foods". fda.gov.

- ↑ Nobel Lectures, Chemistry, 1901–1921. Elsevier. 1966. Reprinted online: "Paul Sabatier, The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1912". Nobel Foundation. Retrieved 7 January 2007.

- ↑ de 141029 Process for converting unsaturated fatty acids or their glycerides into saturated compounds

- ↑ gb 190301515 Process for converting unsaturated fatty acids or their glycerides into saturated compounds

- ↑ Patterson, HBW (1998). "Hydrogenation" (PDF). Sci Lecture Papers Series. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 September 2007. Retrieved 7 January 2007.

- 1 2 "Wilhelm Normann und die Geschichte der Fetthärtung von Martin Fiedler, 2001". 20 December 2011.

- ↑ Shurtleff, William; Akiko Aoyagi. "History of Soybeans and Soyfoods: 1100 B.C. to the 1980s". Archived from the original on 18 October 2005.

- ↑ Fred A. Kummerow (2008). Cholesterol Won't Kill You — But Trans Fat Could. Trafford Publishing. ISBN 1-4251-3808-X.

- 1 2 Ascherio A, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC. "Trans fatty acids and coronary heart disease". Archived from the original on 3 September 2006. Retrieved 14 September 2006.

- ↑ Booyens J, Louwrens CC, Katzeff IE (1988). "The role of unnatural dietary trans and cis unsaturated fatty acids in the epidemiology of coronary artery disease". Medical Hypotheses. 25 (3): 175–182. doi:10.1016/0306-9877(88)90055-2. PMID 3367809.

- 1 2 Willett WC, Ascherio A (1995). "Trans fatty acids: are the effects only marginal?". American Journal of Public Health. 84 (5): 722–4. doi:10.2105/AJPH.84.5.722. PMC 1615057

. PMID 8179036.

. PMID 8179036. - ↑ "Approaches to removing trans fats from the food supply in industrialized and developing countries". European Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 63 (Suppl 1): S50–7. 2009. doi:10.1038/ejcn.2009.14.

- ↑ "Lawsuit dropped as Oreo looks to drop the fat". CNN. 14 May 2003. Retrieved 14 July 2011.

- 1 2 Regulation: 21 CFR 101.9 (c)(2)(ii). Food and Drug Administration (11 July 2003). "21 CFR Part 101. Food labeling; trans fatty acids in nutrition labeling; consumer research to consider nutrient content and health claims and possible footnote or disclosure statements; final rule and proposed rule" (PDF). National Archives and Records Administration. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 January 2007. Retrieved 18 January 2007.

- 1 2 "FDA acts to provide better information to consumers on trans fats". Food and Drug Administration. Archived from the original on 25 June 2005. Retrieved 26 July 2005.

- 1 2 "Newswise: most consumers misinterpret meaning of trans fat information on Nutrition Facts panel". Retrieved 19 June 2008.

- 1 2 Shockman, Luke (5 December 2005). "Trans fat: 'Zero' foods add up". Toledo Blade. Archived from the original on 21 June 2009. Retrieved 18 January 2007.

- ↑ Hadzipetros, Peter (25 January 2007). "Trans Fats Headed for the Exit". CBC News.

- ↑ Spencelayh, Michael (9 January 2007). "Trans fat free future". Royal Society of Chemistry.

- ↑ Udo Erasmus; Fats that heal, Fats that Kill, Alive books, 1993 edition, Pages 13-19.

- ↑ Alonso L, Fontecha J, Lozada L, Fraga MJ, Juárez M (1999). "Fatty acid composition of caprine milk: major, branched-chain, and trans fatty acids". Journal of Dairy Science. 82 (5): 878–84. doi:10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(99)75306-3. PMID 10342226.

- ↑ Alfred Thomas (2002). "Fats and Fatty Oils". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a10_173. ISBN 3-527-30673-0.

- ↑ Casimir C. Akoh, David B. Min., eds. (2002). Food lipids: chemistry, nutrition, and biotechnology. New York: M. Dekker. pp. 1–2. ISBN 0-8247-0749-4.

- ↑ ""fatty acid"". IUPAC Gold book. International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry.

- ↑ Hill, John W & Kolb, Doris K (2007). Chemistry for changing times. Pearson / Prentice Hall. ISBN 0136054498.

- 1 2 "Section 7: Biochemistry" (PDF). Handbook of chemistry and physics. 2007–2008 (88th ed.). Taylor and Francis. 2007. Retrieved 19 November 2007.

- ↑ Eller FJ; List, GR; Teel, JA; Steidley, KR; Adlof, RO (2005). "Preparation of spread oils meeting U.S. Food and Drug Administration labeling requirements for trans fatty acids via pressure-controlled hydrogenation". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 53 (15): 5982–5984. doi:10.1021/jf047849+. PMID 16028984.

- ↑ Maria Teresa Tarrago-Trani, Katherine M. Phillips, Linda E. Lemar, Joanne M. Holden "New and Existing Oils and Fats Used in Products with Reduced Trans-Fatty Acid Content" Journal of the American Dietetic Association 2006, Volume 106, pp. 867–880.doi:10.1016/j.jada.2006.03.010

- 1 2 "Heart Foundation: Butter has 20 times the trans fats of marg | Australian Food News". www.ausfoodnews.com.au.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Trans Fat Task Force (June 2006). "TRANSforming the Food Supply". Retrieved 7 January 2007.

- ↑ Ashok, Chauhan; Ajit, Varma (2009). "Chapter 4: Fatty acids". A Textbook of Molecular Biotechnology. p. 181. ISBN 978-93-80026-37-4.

- ↑ Hunter, JE (2005). "Dietary levels of trans fatty acids" basis for health concerns and industry efforts to limit use". Nutrition Research. 25 (5): 499–513. doi:10.1016/j.nutres.2005.04.002.

- ↑ Innis, Sheila M & King, D Janette (1 September 1999). "trans fatty acids in human milk are inversely associated with concentrations of essential all-cis n-6 and n-3 fatty acids and determine trans, but not n-6 and n-3, fatty acids in plasma lipids of breast-fed infants". American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 70 (3): 383–390. PMID 10479201.

- ↑ NYC Board of Health. "Board of Health Approves Regulation to Phase Out Artificial Trans Fat: FAQ". Archived from the original on 6 October 2006. Retrieved 7 January 2007.

- ↑ "What's in that french fry? Fat varies by city". MSNBC. 12 April 2006. Retrieved 7 January 2007. AP story concerning PMID 16611965

- ↑ Food and nutrition board, institute of medicine of the national academies (2005). Dietary Reference Intakes for Energy, Carbohydrate, Fiber, Fat, Fatty Acids, Cholesterol, Protein, and Amino Acids (Macronutrients). National Academies Press. pp. i.

- ↑ Food and nutrition board, institute of medicine of the national academies (2005). Dietary Reference Intakes for Energy, Carbohydrate, Fiber, Fat, Fatty Acids, Cholesterol, Protein, and Amino Acids (Macronutrients). National Academies Press. p. 447.

- 1 2 3 4 Mozaffarian D, Katan MB, Ascherio A, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC (2006). "Trans Fatty Acids and Cardiovascular Disease". New England Journal of Medicine. 354 (15): 1601–1613. doi:10.1056/NEJMra054035. PMID 16611951.

- ↑ Food and nutrition board, institute of medicine of the national academies (2005). Dietary Reference Intakes for Energy, Carbohydrate, Fiber, Fat, Fatty Acids, Cholesterol, Protein, and Amino Acids (Macronutrients). National Academies Press. p. 424.

- ↑ National Dairy Council (18 June 2004). "comments on 'Docket No. 2003N-0076 Food Labeling: Trans Fatty Acids in Nutrition Labeling'" (PDF). Retrieved 7 January 2007.

- ↑ Brouwer, I. A.; Wanders, A. J.; Katan, M. B. (2010). Reitsma, Pieter H, ed. "Effect of Animal and Industrial Trans Fatty Acids on HDL and LDL Cholesterol Levels in Humans – A Quantitative Review". PLoS ONE. 5 (3): e9434. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0009434. PMC 2830458

. PMID 20209147.

. PMID 20209147. - ↑ Tricon S, Burdge GC, Kew S, et al. (September 2004). "Opposing effects of cis-9,trans-11 and trans-10,cis-12 conjugated linoleic acid on blood lipids in most healthy humans". Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 80 (3): 614–20. PMID 15321800.

- ↑ Zulet MA, Marti A, Parra MD, Martínez JA (September 2005). "Inflammation and conjugated linoleic acid: mechanisms of action and implications for human health". J. Physiol. Biochem. 61 (3): 483–94. doi:10.1007/BF03168454. PMID 16440602.

- 1 2 "Trans fatty acid isomers in human health and in the food industry". Biological Research. 32 (4). 1999. PMID 10983247.

- ↑ Booyens J, Louwrens CC, Katzeff IE (1988). "The role of unnatural dietary trans and cis unsaturated fatty acids in the epidemiology of coronary artery disease.". Med Hypotheses. 25 (3): 175–82. doi:10.1016/0306-9877(88)90055-2. PMID 3367809.

- ↑ Kummerow FA1, Zhou Q, Mahfouz MM, Smiricky MR, Grieshop CM, Schaeffer DJ (2004). "Trans fatty acids in hydrogenated fat inhibited the synthesis of the polyunsaturated fatty acids in the phospholipid of arterial cells.". Life Sci. 74 (22): 2707–23. doi:10.1016/j.lfs.2003.10.013. PMID 15043986.

- ↑ Mozaffarian D, Katan MB, Ascherio A, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC (2003). "Influence of trans fatty acids on infant and fetus development". Acta Microbiologica Polonica. 52: 67–74. PMID 15058815.

- ↑ Koletzko B, Decsi T (1997). "Metabolic aspects of trans fatty acids". Clin Nutr. 16 (5): 229–37. doi:10.1016/s0261-5614(97)80034-9. PMID 16844601.

- ↑ Menaa F, Menaa A, Menaa B, Tréton J (2013). "Trans-fatty acids, dangerous bonds for health?". Eur J Nutr. 52 (4): 1289–302. doi:10.1007/s00394-012-0484-4. PMID 23269652.

- ↑ Ulf Riserus (2006). "Trans fatty acids, insulin sensitivity and type 2 diabetes". Scandinavian Journal of Food and Nutrition. 50 (4): 161–165. doi:10.1080/17482970601133114.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Trans Fat Task Force (June 2006). "TRANSforming the Food Supply (Appendix 9iii)". Archived from the original on 25 February 2007. Retrieved 9 January 2007. (Consultation on the health implications of alternatives to trans fatty acids: Summary of Responses from Experts)

- ↑ Zaloga GP, Harvey KA, Stillwell W, Siddiqui R (2006). "Trans Fatty Acids and Coronary Heart Disease". Nutrition in Clinical Practice. 21 (5): 505–512. doi:10.1177/0115426506021005505. PMID 16998148.

- ↑ Mozaffarian D, Katan MB, Ascherio A, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC (2006). "Trans fatty acids and cardiovascular disease". N. Engl. J. Med. 354 (15): 1601–13. doi:10.1056/NEJMra054035. PMID 16611951.

- 1 2 Hu, FB (1997). "Dietary fat intake and the risk of coronary heart disease in women". New England Journal of Medicine (PDF). 337 (21): 1491–1499. doi:10.1056/NEJM199711203372102. PMID 9366580.

- ↑ Oh, K; Hu, FB; Manson, JE; Stampfer, MJ; Willett, WC (2005). "Dietary fat intake and risk of coronary heart disease in women: 20 years of follow-up of the nurses' health study". American Journal of Epidemiology. 161 (7): 672–679. doi:10.1093/aje/kwi085. PMID 15781956.

- ↑ "Trans fatty acids and coronary heart disease". New England Journal of Medicine. 340 (25): 1994–1998. 1999. doi:10.1056/NEJM199906243402511. PMID 10379026.

- ↑ Mensink, RPM; Katan, MB (1990). "Effect of dietary trans fatty acids on high-density and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels in healthy subjects". N Engl J Med. 323: 439–45. doi:10.1056/NEJM199008163230703.

- ↑ Mensink; et al. (2003). "Effects of dietary fatty acids and carbohydrates on the ratio of serum total to HDL cholesterol and on serum lipids and apolipoproteins: a meta-analysis of 60 controlled trials". American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 77 (5): 1146–55. PMID 12716665.

- ↑ Gatto, Lissa M; Sullivan,David R; Samman, Samir (2003). "Postprandial effects of dietary trans fatty acids on apolipoprotein(a) and cholesteryl ester transfer" (PDF). Am J Clin Nutr. 77 (5): 1119–1124. PMID 12716661.

- ↑ Lopez-Garcia, Esther; S; M; M; R; S; W; H (2005). "Consumption of Trans Fatty Acids Is Related to Plasma Biomarkers of Inflammation and Endothelial Dysfunction". The Journal of Nutrition. 135 (3): 562–566. PMID 15735094.

- ↑ Morris MC, Evans DA, Bienias JL, Tangney CC, Bennett DA, Aggarwal N, Schneider J, Wilson RS (2003). "Dietary fats and the risk of incident Alzheimer disease". Arch Neurol. 60 (2): 194–200. doi:10.1001/archneur.60.2.194. PMID 12580703.

- 1 2 Phivilay, A. (2009). "High dietary consumption of trans fatty acids decreases brain docosahexaenoic acid but does not alter amyloid-β and tau pathologies in the 3xTg-AD model of Alzheimer's disease". Neuroscience. 159 (1): 296–307. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.12.006. PMID 19135506.

- ↑ Granholm, A. C.; Bimonte-Nelson, H. A.; Moore, A. B.; Nelson, M. E.; Freeman, L. R.; Sambamurti, K. (2008). "Effects of a saturated fat and high cholesterol diet on memory and hippocampal morphology in the middle-aged rat". Journal of Alzheimer's disease : JAD. 14 (2): 133–145. PMC 2670571

. PMID 18560126.

. PMID 18560126. - ↑ American Cancer Society. "Common questions about diet and cancer". Retrieved 9 January 2007.

- ↑ Jorge, Chavarro; Meir Stampfer; Hannia Campos; Tobias Kurth; Walter Willett; Jing Ma (1 April 2006). "A prospective study of blood trans fatty acid levels and risk of prostate cancer". Proc. Amer. Assoc. Cancer Res. American Association for Cancer Research. 47 (1): 943. Retrieved 9 January 2007.

- ↑ Brasky, T. M.; Till, C.; White, E.; Neuhouser, M. L.; Song, X.; Goodman, P.; Thompson, I. M.; King, I. B.; Albanes, D.; Kristal, A. R. (2011). "Serum Phospholipid Fatty Acids and Prostate Cancer Risk: Results from the Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial". American Journal of Epidemiology. 173 (12): 1429–1439. doi:10.1093/aje/kwr027. PMC 3145396

. PMID 21518693.

. PMID 21518693. - ↑ "Breast cancer: a role for trans fatty acids?". World Health Organization (Press release). 11 April 2008. Archived from the original on 13 April 2008.

- ↑ Chajès V, A. Thiébaut CM, Rotival M, Gauthier E, Maillard V; Boutron-Ruault MC, Joulin V, Lenoir GM, Clavel-Chapelon F (2008). "Association between serum trans-monounsaturated fatty acids and breast cancer risk in the E3N-EPIC Study". Am. J. Epidemiol. 167 (11): 1312–20. doi:10.1093/aje/kwn069. PMC 2679982

. PMID 18390841.

. PMID 18390841. - ↑ Hu FB, van Dam RM, Liu S (2001). "Diet and risk of Type II diabetes: the role of types of fat and carbohydrate". Diabetologia. 44 (7): 805–817. doi:10.1007/s001250100547. PMID 11508264.

- ↑ van Dam RM, Stampfer M, Willett WC, Hu FB, Rimm EB (2002). "Dietary fat and meat intake in relation to risk of type 2 diabetes in men". Diabetes Care. 25 (3): 417–424. doi:10.2337/diacare.25.3.417. PMID 11874924.

- ↑ Gosline, Anna (12 June 2006). "Why fast foods are bad, even in moderation". New Scientist. Retrieved 9 January 2007.

- ↑ "Six years of fast-food fats supersizes monkeys". New Scientist (2556): 21. 17 June 2006.

- 1 2 Kavanagh, K; Jones, KL; Sawyer, J; Kelley, K; Carr, JJ; Wagner, JD; Rudel, LL (15 July 2007). "Trans fat diet induces abdominal obesity and changes in insulin sensitivity in monkeys". Obesity (Silver Spring). 15 (7): 1675–84. doi:10.1038/oby.2007.200. PMID 17636085.

- ↑ Thompson Tommy G. "Trans Fat Press Conference". Archived from the original on 10 July 2006., US Secretary of health and human services

- ↑ Mahfouz M (1981). "Effect of dietary trans fatty acids on the delta 5, delta 6 and delta 9 desaturases of rat liver microsomes in vivo". Acta biologica et medica germanica. 40 (12): 1699–1705. PMID 7345825.

- ↑ Chavarro Jorge E, Rich-Edwards Janet W, Rosner Bernard A, Willett Walter C (January 2007). "Dietary fatty acid intakes and the risk of ovulatory infertility". American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 85 (1): 231–237. PMID 17209201.

- ↑ Roan, Shari (28 January 2011). "Trans fats and saturated fats could contribute to depression". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 8 February 2011.

- ↑ McNamara, Robert, K.; Chang-Gyu Han; Ronald Jandacek; Therese Rider; Patrick Tso; Kevin E. Stanford; Neil M. Richtand (2007). "Selective Deficits in the Omega-3 Fatty Acid Docosahexaenoic Acid in the Postmortem Orbitofrontal Cortex of Patients with Major Depressive Disorder". Biological Psychiatry. 62 (1): 17–24. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.08.026. PMID 17188654.

- ↑ Golomb, Beatrice A.; Evans, Marcella A.; White, Halbert L.; Dimsdale, Joel E. (2012). "Trans Fat Consumption and Aggression". PLoS ONE. 7 (3): e32175. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0032175.