Parotid gland

| Parotid gland | |

|---|---|

| |

| Details | |

| Artery | transverse facial artery |

| Vein | external jugular vein |

| Nerve |

Glossopharyngeal nerve otic ganglion |

| Lymph | preauricular deep parotid lymph nodes |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | Glandula parotis or glandula parotidea |

| MeSH | A03.556.500.760.464 |

| TA | A05.1.02.003 |

| FMA | 59790 |

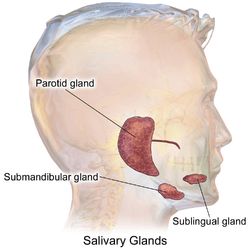

The parotid gland is a major salivary gland in many animals. In humans, the two parotid glands are present on either side of the mouth and in front of both ears. They are the largest of the salivary glands. Each parotid is wrapped around the mandibular ramus, and secretes serous saliva through the parotid duct into the mouth, to facilitate mastication and swallowing and to begin the digestion of starches.

The word parotid (paraotic) literally means "beside the ear".

Structure

The parotid glands are a pair of mainly serous salivary glands located below and in front of each ear canal, draining their secretions into the vestibule of the mouth through the parotid duct.[1] Each gland lies behind the mandibular ramus and in front of the mastoid process of the temporal bone. The gland can be felt on either side, by feeling in front of each ear, along the cheek, and below the angle of the mandible.[2] The gland is roughly wedge-shaped when seen from the surface.

The parotid duct, a long excretory duct, emerges from the front of each gland, superficial to the masseter muscle. The duct pierces the buccinator muscle, then opens into the mouth on the inner surface of the cheek, usually opposite the maxillary second molar. The parotid papilla is a small elevation of tissue that marks the opening of the parotid duct on the inner surface of the cheek.[3]

The gland has four surfaces — superficial or lateral, superior, anteromedial, and posteromedial. The gland has three borders — anterior, medial, and posterior. The parotid gland has two ends — superior end in the form of small superior surface and an inferior end (apex).

A number of different structures pass through the gland. From lateral to medial, these are:

- Facial nerve

- Retromandibular vein

- External carotid artery

- Superficial temporal artery

- Branches of the great auricular nerve

- Maxillary artery

Location

- Superficial or lateral relations: The gland is situated deep to the skin, superficial fascia, superficial lamina of investing layer of deep cervical fascia and great auricular nerve (anterior ramus of C2 and C3).

- Anteromedial relations: The gland is situated posterolaterally to the mandibular ramus, masseter and medial pterygoid muscles. A part of the gland may extend between the ramus and medial pterygoid, as the pterygoid process. Branches of facial nerve and parotid duct emerge through this surface.

- Posteromedial relations: The gland is situated anterolaterally to mastoid process of temporal bone with its attached sternocleidomastoid and digastric muscles, styloid process of temporal bone with its three attached muscles (stylohyoid, stylopharyngeus, and styloglossus) and carotid sheath with its contained neurovasculature (internal carotid artery, internal jugular vein, and 9th, 10th, 11th, and 12th cranial nerves).

- Medial relations: The parotid gland comes into contact with the superior pharyngyeal constrictor muscle at the medial border, where the anteromedial and posteromedial surfaces meet. Hence, a need exists to examine the fauces in parotitis.

Blood supply

The external carotid artery and its terminal branches within the gland, namely, the superficial temporal and the maxillary arteries, supply the parotid gland. Venous return is to the retromandibular vein.

Lymphatic drainage

The gland is mainly drained into the preauricular or parotid lymph nodes which ultimately drain to the deep cervical chain.

Nerve supply

The parotid gland receives both sensory and autonomic innervation. Sensory innervation is supplied by the auriculotemporal nerve, a branch of the mandibular nerve. The autonomic innervation controls the rate of saliva production and is supplied by the glossopharyngeal nerve.[4] Postganglionic sympathetic fibers from superior cervical sympathetic ganglion reach the gland as periarterial nerve plexuses around the external carotid artery, and their function is mainly vasoconstriction. The cell bodies of the preganglionic sympathetics usually lie in the lateral horns of upper thoracic spinal segments. Preganglionic parasympathetic fibers leave the brain stem from inferior salivatory nucleus in the glossopharyngeal nerve and then through its tympanic and then the lesser petrosal branch pass into the otic ganglion. There, they synapse with postganglionic fibers which reach the gland by hitch-hiking via the auriculotemporal nerve, a branch of the mandibular nerve.[5][6]

Microanatomy

The gland has a capsule of its own of dense connective tissue, but is also provided with a false capsule by investing layer of deep cervical fascia. The fascia at the imaginary line between the angle of mandible and mastoid process splits into the superficial lamina and a deep lamina to enclose the gland. The risorius is a small muscle embedded with this capsule substance.

The gland has short, striated ducts and long, intercalated ducts.[7] The intercalated ducts are also numerous and lined with cuboidal epithelial cells, and have lumina larger than those of the acini. The striated ducts are also numerous and consist of simple columnar epithelium, having striations that represent the infolded basal cell membranes and mitochondria.[8]

Though the parotid gland is the largest, it provides only 25% of the total salivary volume. The serous cell predominates in the parotid, making the gland secrete a mainly serous secretory product.[7]

The parotid gland also secretes salivary alpha-amylase (sAA), which is the first step in the decomposition of starches during mastication. It is the main exocrine gland to secrete this. It breaks down amylose (straight chain starch) and amylopectin (branched starch) by hydrolyzing alpha 1,4 bonds. Additionally, the alpha amylase has been suggested to prevent bacterial attachment to oral surfaces and to enable bacterial clearance from the mouth.[9]

Development

The parotid salivary glands appear early in the sixth week of prenatal development and are the first major salivary glands formed. The epithelial buds of these glands are located on the inner part of the cheek, near the labial commissures of the primitive mouth (from ectodermal lining near angles of the stomodeum in the 1st/2nd pharyngeal arches; the stomodeum itself is created from the rupturing of the oropharyngeal membrane at about 26 days.[10]) These buds grow posteriorly toward the otic placodes of the ears and branch to form solid cords with rounded terminal ends near the developing facial nerve. Later, at around 10 weeks of prenatal development, these cords are canalized and form ducts, with the largest becoming the parotid duct for the parotid gland. The rounded terminal ends of the cords form the acini of the glands. Secretion by the parotid glands via the parotid duct begins at about 18 weeks of gestation. Again, the supporting connective tissue of the gland develops from the surrounding mesenchyme.[7]

Clinical significance

Parotitis

Inflammation of one or both parotid glands is known as parotitis. The most common cause of parotitis is mumps. Widespread vaccination against mumps has markedly reduced the incidence of mumps parotitis. The pain of mumps is due to the swelling of the gland within its fibrous capsule.[1]

Apart from viral infection, other infections, such as bacterial, can cause parotitis (acute suppurative parotitis or chronic parotitis). These infections may cause blockage of the duct by salivary duct calculi or external compression. Parotid gland swellings can also be due to benign lymphoepithelial lesions caused by Mikulicz disease and Sjögren syndrome. Swelling of the parotid gland may also indicate the eating disorder bulimia nervosa, creating the look of a heavy jaw line. With the inflammation of mumps or obstruction of the ducts, increased levels of the salivary alpha amylase secreted by the parotid gland can be detected in the blood stream.

Fibrous reactions

Tuberculosis and syphilis can cause granuloma formation in the parotid glands.

Salivary stones

Salivary stones mainly occur within the main confluence of the ducts and within the main parotid duct. The patient usually complains of intense pain when salivating and tends to avoid foods which produce this symptom. In addition, the parotid gland may become enlarged upon trying to eat. The pain can be reproduced in clinic by squirting lemon juice into the mouth. Surgery depends upon the site of the stone: if within the anterior aspect of the duct, a simple incision into the buccal mucosa with sphinterotomy may allow removal; however, if situated more posteriorly within the main duct, complete gland excision may be necessary.

Injury

The parotid salivary gland can also be pierced and the facial nerve temporarily traumatized when an inferior alveolar local anesthesia nerve block is incorrectly administered, causing transient facial paralysis.[2]

Cancer and tumours

About 80% of tumors of the parotid gland are benign.[11] The most common of these include pleomorphic adenoma (70% of tumors,[11] affecting predominantly females (60%[11])) and Warthin tumor (i.e. adenolymphoma) more in males than in females. Their importance is in relation to their anatomical position and tendency to grow over time. The tumorous growth can also change the consistency of the gland and cause facial pain on the involved side.[12]

Around 20% of parotid tumors are malignant, with the most common tumors being mucoepidermoid carcinoma and adenoid cystic carcinoma. Other malignant tumors of the parotid gland include acinic cell carcinoma, carcinoma expleomorphic adenoma, adenocarcinoma (arising from ductal epithelium of parotid gland), squamous cell carcinoma (arising from parenchyma of parotid gland), and undifferentiated carcinoma. Metastasis from other sites like phyllodes tumour of breast presenting as parotid swelling have also been described.[13] Critically, the relationship of the tumor to the branches of the facial nerve (CN VII) must be defined because resection may damage the nerves, resulting in paralysis of the muscles of facial expression.

Surgery

Surgical treatment of parotid gland tumors is sometimes difficult because of the anatomical relations of the facial nerve parotid lodge, as well as the increased potential for postoperative relapse. Thus, detection of early stages of a parotid tumor is extremely important in terms of postoperative prognosis.[11] Operative technique is laborious, because of relapses and incomplete previous treatment made in other border specialties.[11]

After surgical removal of the parotid gland (Parotidectomy), the auriculotemporal nerve is liable to damage and upon recovery it fuses with sweat glands. This can cause sweating on the cheek on the side of the face of the affected gland. This condition is known as Frey's syndrome.[14]

Additional images

- Parotid gland (incorrect muscle name)

Mandibular division of the trifacial (trigeminal) nerve

Mandibular division of the trifacial (trigeminal) nerve

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Parotid gland. |

References

- 1 2 Human Anatomy, Jacobs, Elsevier, 2008, page 193

- 1 2 Illustrated Anatomy of the Head and Neck, Fehrenbach and Herring, Elsevier, 2012, p. 154

- ↑ lllustrated Anatomy of the Head and Neck, Fehrenbach and Herring, Elsevier, 2012, p. 154.

- ↑ "The Parotid Gland". TeachMeAntatomy.info. Retrieved 11 November 2015.

- ↑ Ten Cate's Oral Histology, Nanci, Elsevier, 2013, page 255

- ↑ McMinn's clinical atlas of human anatomy, Abrahams, et al, Elsevier, 2008, page 54

- 1 2 3 Illustrated Dental Embryology, Histology, and Anatomy, Bath-Balogh and Fehrenbach, Elsevier, 2011, page 135

- ↑ Ten Cate's Oral Histology, Nanci, Elsevier, 2013, page 273

- ↑ Arhakis A, Karagiannis V, Kalfas S (2013). "Salivary alpha-amylase activity and salivary flow rate in young adults". The Open Dentistry Journal. 7: 7–15. doi:10.2174/1874210601307010007. PMC 3601341

. PMID 23524385.

. PMID 23524385. - ↑ Moore, Persaud (2003). The Developing Human (7th ed.). Saunders. pp. 203, 220. ISBN 0-8089-2265-3.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Alexandru Bucur; Octavian Dincă; Tiberiu Niță; Cosmin Totan; Cristian Vlădan (Mar 2011). "Parotid tumors: our experience". Rev. chir. oro-maxilo-fac. implantol. 2 (1): 7–9. ISSN 2069-3850.(webpage has a translation button)

- ↑ Fehrenbach; Herring "Illustrated Head and Neck Anatomy", Elsevier, 2012, p. 154

- ↑ Sivaram, P., Jayan, C., Sulfekar, M. S., & Rahul, M. (2015). "Metastatic Malignant Phyllodes Tumour: An Interesting Presentation as a Parotid Swelling". New Indian Journal of Surgery. 6 (3): 75–77.

- ↑ Office of Rare Diseases Research (2011). "Frey's syndrome". National Institutes of Health. Retrieved 17 December 2012.

External links

- Illustration at yoursurgery.com

- lesson4 at The Anatomy Lesson by Wesley Norman (Georgetown University)

- Salivary gland infections from Medline Plus

- Salivary gland cancer from American Cancer Society