Parking

Parking is the act of stopping and disengaging a vehicle and leaving it unoccupied. Parking on one or both sides of a road is often permitted, though sometimes with restrictions. Some buildings have parking facilities for use of the buildings' users. Countries and local governments have rules for design and use of parking spaces.

Parking facilities

.jpg)

facilities include indoor and outdoor private property belonging to a house, the side of the road where metered or laid out for such use, a parking lot (North American English) or car park (British English), indoor and outdoor multi-level structures, shared underground parking facilities, and facilities for particular types of vehicle such as dedicated structures for cycle parking.

In the U.S., after the first public parking garage for motor vehicles was opened in Boston, May 24, 1898, livery stables in urban centers began to be converted into garages.[1] In cities of the Eastern US, many former livery stables, with lifts for carriages, continue to operate as garages today.

The following terms give regional variations. All except carport refer to outdoor multi-level parking facilities. In some regional dialects, some of these phrases refer also to indoor or single-level facilities.

- Parking ramp (used in some parts of the upper Midwestern United States, especially Minneapolis, but sometimes seen as far east as Buffalo, New York). Elsewhere, the term "ramp" would apply to the inclines between floors of a parking garage, but not to the entire structure itself.

- Multi-storey car park

- Car park (UK, Ireland, Hong Kong, South Africa; usually single-level)

- Parking structure (Western U.S.)

- Parking garage (Canada and USA, where this term does not always distinguish between outdoor above-ground multi-level parking and indoor underground parking.)

- Parking building (New Zealand)

- Carport (open-air single-level covered parking)

- Cycle park (UK, Hong Kong)

- Parkade (Canada, South Africa)

In addition to basic car parking/parking lots variations of serviced parking types exist. Common serviced parking types are:

- Park and ride

- Valet Parking

- Airport Parking

- Meet and Greet Parking

- Park and Fly Parking

Parking spaces may be variously arranged.

Parking lots specifically for bicycles are becoming more prevalent in many countries. These may include bicycle parking racks and locks, as well as more modern technologies for security and convenience.[2] For instance, one bicycle parking lot in Tokyo has an automated parking system.[3]

Economics of parking

Urban parking spaces can have a high value where the price of land is high. In Boston in 2009 a single parking space sold for $300,000.[5]

In congested urban areas parking of motor vehicles is time-consuming and often expensive. Urban planners who are in a position to override market forces must consider whether and how to accommodate or 'demand manage' potentially large numbers of motor vehicles in small geographic areas. Usually the authorities set minimum, or more rarely maximum, numbers of motor vehicle parking spaces for new housing and commercial developments, and may also plan their location and distribution to influence their convenience and accessibility. The costs or subsidies of such parking accommodations can become a heated point in local politics. For example, in 2006 the San Francisco Board of Supervisors considered a controversial zoning plan to limit the number of motor vehicle parking spaces available in new residential developments.[6]

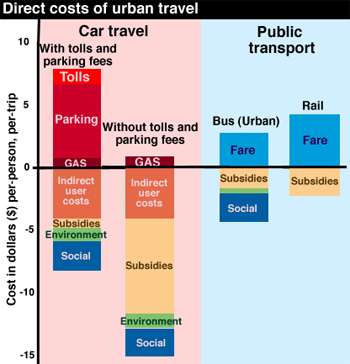

In the graph to the right the value above the line represents the out-of-pocket cost per trip, per person for each mode of transportation; the value below the line shows subsidies, environmental impact, social and indirect costs. When cities charge market rates for on-street parking and municipal parking garages for motor vehicles, and when bridges and tunnels are tolled for these modes, driving becomes less competitive in terms of out-of-pocket costs compared to other modes of transportation. When municipal motor vehicle parking is underpriced and roads are not tolled, the shortfall in tax expenditures by drivers, through fuel tax and other taxes, might be regarded as a very large subsidy for automobile use: much greater than common subsidies for the maintenance of infrastructure and discounted fares for public transportation.[4]

Where car parking spaces are a scarce commodity, and owners have not made suitable arrangements for their own parking, ad hoc overspill parking often takes place along sections of road where there is no planned scheme by a municipal authority to allocate roadspace. Heated social discourse sometimes revolves around the sense of "ownership" that informally arises. Many use parking chairs and other markers, usually without approval of municipal authorities.

For example, during the winter of 2005 in Boston, the practice of some people saving convenient roadway for themselves became controversial. At that time, many Boston districts had an informal convention that if a person shoveled the snow out of a roadspace, that person could claim ownership of that space with a marker.[7] However, city government defied that custom and cleared markers out of spaces.[8]

Festivals and sporting events often spawn a cottage industry of parking. Homeowners, schools, and businesses often make extra money by charging a flat-rate fee for all-day parking during the event. In some countries, such "cottage industry parking" has become large-scale business. The UK airport parking industry is currently estimated to be worth 1.3 billion GBP per year.

According to the International Parking Institute, "parking is a $25 billion industry and plays a pivotal role in transportation, building design, quality of life and environmental issues".[9]

Some airports charge more for parking cars than for parking aircraft.[10]

Parking control is primarily an issue in densely populated cities in advanced countries, where the great demand for parking spaces makes them expensive and difficult. In urban locations parking control is a developing subject. Parking restrictions may be public or private. Local government, as opposed to central government, is the primary activator in public parking. The emphasis is on restriction of on-street parking facilities; and parking charges and fines are often major income sources for local government in North America and Europe.

Typically, communication about the parking status of a roadway takes the form of notices, e.g. fixed to a nearby wall and/or road markings. Part of the requirements for passing the driving test in some countries is to demonstrate understanding of parking signs.

Motorists parking on-street in big cities often have to pay for the time the vehicle is on the spot. There are fines for overstay. The motorist is often required to display a sticker beneath the windscreen indicating that he has paid for the parking space usage for an allocated time period. Private parking control includes both residential and corporate property. Owners of private property use signs indicating that parking facilities are restricted to certain categories of people such as the owners themselves and their guests, or staff members and permitted contractors only.

It is often necessary not only to communicate parking restrictions, but also to have available a workable deterrent. The deterrent can take physical forms such as vehicle immobilisation exemplified by the wheel clamp, and non-physical forms such as levying parking charges on the registered vehicle owners. Sometimes photography is used to record violations.

On both public and private land, physical restrictions include: parking bollards, parking poles that swivel from horizontal to vertical, gated entry and exit with time-dependent charges. This is an expanding subject.

Performance parking

Donald C. Shoup in 2005 argued in his book, The High Cost of Free Parking, against the large-scale use of land and other resources in urban and suburban areas for motor vehicle parking.[11] Shoup's work has been popularized along with market-rate parking and performance parking, both of which raise and lower the price of metered street parking with the goal of reducing cruising for parking and double parking without overcharging for parking.

"Performance parking" or variable-rate parking is based on Dr Shoup's ideas. Electronic parking meters are used so that parking spaces in desirable locations and at desirable times are more expensive than less desirable locations. Other variations include rising rates based on duration of parking. More modern ideas use sensors and networked parking meters which "bid up" (or down) the price of parking automatically with the goal of keeping 85–90% of the spaces in use at any given time to ensure perpetual parking availability. These ideas have been implemented in Redwood City, California[12] and are being implemented in San Francisco[13] and Los Angeles.[14]

One empirical study supports performance-based pricing by analyzing the block-level price elasticity of parking demand in the SFpark context.[15] The study suggests that block-level elasticities vary so widely that urban planners and economists cannot accurately predict the response in parking demand to a given change in price. The public policy implication is that planners should utilize observed occupancy rates in order to adjust prices so that target occupancy rates are achieved. Effective implementation will require further experimentation with and assessment of the tâtonnement process.

Fringe parking

Fringe parking is an area for parking usually located outside the central business district and most often used by suburban residents who work or shop downtown.

Statistics

Parking Generation is a document produced by the Institute of Transportation Engineers (ITE) that assembles a vast array of parking demand observations predominately from the United States. It summarizes the amount of parking observed with various land uses at different times of the day/week/month/year including the peak parking demand. While it has been assailed by some planners for lack of data in urban settings, it stands as the single largest accumulation of actual parking demand data related to land use. Anyone can submit parking demand data for inclusion. The report is updated approximately every 5 to 10 years.

Finding parking

Mobile apps that help drivers find parking take different approaches, including:

- ParkWhiz, SpotHero, and JustPark which allows for mobile booking at participating lots, garages and hotels,[16] checking availability

- MonkeyParking, which lets drivers departing a parking space sell that information to drivers looking for parking. This type of app has been outlawed in Boston and San Francisco.[17]

- Vallie, an on demand valet parking service that meets users in Central London, parks their vehicle and then delivers it subsequently[18]

Some connected cars have mobile apps associated with the in-car system, that can locate the car or indicate the last place it was parked. Cars with Internavi communicate to each other indicating recently vacated spots.

San Francisco uses a system called SFpark, which has sensors embedded in the roadway. It allows drivers to find parking via mobile app, web site, or SMS, and includes "smart" parking meters and garages that use variable pricing based on time and location to keep approximately 15% of parking spaces open. Some South Boston spots also have sensors, so users of an app called Parker can find vacancies.[19]

Ford Motor Company is developing a system called Parking Spotter which allows vehicles to upload parking spot information into the cloud for other drivers to access.[20]

Parking guidance and information system provides information about the availability of parking spaces within a controlled area. The systems may include vehicle detection sensors that can count the number of available spaces and display the information on various signs. There may be indicator lights that can lead drivers to an exact available spot.[21]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Parking. |

References

- ↑ Shannon Sanders McDonald: The parking garage. Design and evolution of a modern urban form, Washington 2007, p. 7-21

- ↑ "The Guide to Parking Lots". Discount Park & Ride. 9 January 2015. Retrieved 27 March 2015.

- ↑ "Invisible Bicycles: Tokyo's High-Tech Underground Bike Parking". Web Urbanist. 26 March 2015. Retrieved 27 March 2015.

- 1 2 Graph based on data from Vukan R. Vuchic, Transportation for Livable Cities, p. 76. 1999. ISBN 0-88285-161-6

- ↑ Woolhouse, Megan (2009-06-10). "Back Bay parking space sells for record $300,000". The Boston Globe. Retrieved 2010-07-22.

- ↑ Vega, Cecilia (2006-02-07). "Supes to consider limit on parking spaces at new buildings". San Francisco Chronicle. pp. B – 2. Retrieved 2008-04-10.

- ↑ "Snow chairs". Boston Online. Retrieved 2008-04-10.

- ↑ Finer, Jonathan (2005-01-01). "Boston Fights Winter Parking Tradition". Washington Post. pp. A02. Retrieved 2008-04-10.

- ↑ "IPI". International Parking Institute.

- ↑ "Letters: Cheaper to park a plane than a car at airport". The Age. Melbourne. 2012-04-21.

- ↑ The High Cost of Free Parking by Donald C. Shoup

- ↑ "Redwood City Redevelopment | Downtown Parking". Ci.redwood-city.ca.us. Retrieved 2013-01-12.

- ↑ "SFpark". SFpark. 2012-12-17. Retrieved 2013-01-12.

- ↑ "LADOT ParkingInfo". Expresspark.lacity.org. Retrieved 2013-01-12.

- ↑ Shriver, Adam. "Understanding the Block-Level Price Elasticity of On-Street Parking Demand: A Case Study of San Francisco's SFpark Project". ResearchGate. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

- ↑ "How does OnePark help Accor making its lots profitable". Maddyness.com. Retrieved 8 July 2015.

- ↑ "Parking App Haystack Banned in Boston". Boston.com. Retrieved 13 October 2015.

- ↑ "Vallie Homepage". Retrieved 19 July 2016.

- ↑ "Do new parking apps pass the test? - The Boston Globe". BostonGlobe.com. Retrieved 13 October 2015.

- ↑ Autoblog Staff (14 April 2015). "Translogic 174: Ford envisions the future of parking". Autoblog. Retrieved 13 October 2015.

- ↑ Idris, M.Y.I.; Leng, Y.Y.; Tamil, E.M.; Noor, N.M.; Razak, Z. (1 February 2009). "Car Park System: A Review of Smart Parking System and its Technology". Information Technology Journal. 8 (2): 101–113. doi:10.3923/itj.2009.101.113. Retrieved 24 September 2015.