Paris, Texas

| Paris, Texas | |

|---|---|

| City | |

|

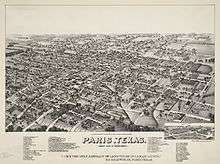

Historic downtown Paris | |

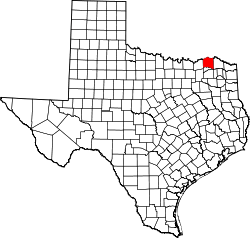

Location of Lamar County | |

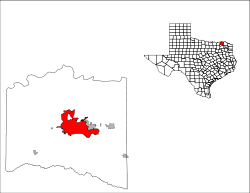

| |

| Coordinates: 33°39′45″N 95°32′52″W / 33.66250°N 95.54778°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Texas |

| County | Lamar |

| Government | |

| • City Council |

Mayor Dr. Anjumand Hashmi Aaron Jenkins Billie Sue Lancaster John Wright Richard Grossnickle Matt Frierson Cleonne Holmes Drake |

| • City Manager | John Godwin |

| Area | |

| • Total | 44.4 sq mi (115.0 km2) |

| • Land | 42.8 sq mi (110.7 km2) |

| • Water | 1.7 sq mi (4.3 km2) |

| Elevation | 600 ft (183 m) |

| Population (2000) | |

| • Total | 25,898 |

| • Density | 605.7/sq mi (233.9/km2) |

| Time zone | Central (CST) (UTC−6) |

| • Summer (DST) | CDT (UTC−5) |

| ZIP codes | 75460-75462 |

| Area code(s) | 903/430 |

| FIPS code | 48-55080 |

| GNIS feature ID | 1364810[1] |

| Website | paristexas.gov |

Paris, Texas is a city and county seat of Lamar County, Texas, United States. As of the 2010 census, the population of the city was 25,171. It is situated in Northeast Texas at the western edge of the Piney Woods, and 98 miles (158 km) northeast of the Dallas–Fort Worth Metroplex. Physio-graphically, these regions are part of the West Gulf Coastal Plain.[2]

Following a tradition of American cities named "Paris", the city commissioned a 65-foot (20 m) replica of the Eiffel Tower in 1993 and installed it in the square. In 1998, presumably as a response to the 1993 construction of a 60-foot (18 m) tower in Paris, Tennessee, the city placed a giant red cowboy hat atop its tower. The current tower is at least the second Eiffel Tower replica built in Paris; the first was constructed of wood and later destroyed by a tornado.

History

Lamar County was first settled to the west of Jonesborough and Clarksville. A settlement on the Red River was named Fulton, one developed at what is now called Emberson, one to the southeast of that near where today is the North Lamar school complex, a fourth, Pinhook, developed southwest of that at the Chisum-Johnson community; another group pioneers settled to the east at Moore's Springs.

In late 1839, George W. Wright moved from his farm northeast of Clarksville to a hill where he had purchased 1,000 acres of unoccupied land. It was on the old road from the mouth of the Kiomatia River at its confluence with the Red River to the Grand Prairie. Wright opened a general store on the road. By December 1840 a new county had been formed, named for Republic of Texas President Mirabeau B. Lamar. By September 1841 Wright's store was called Paris and served as the local postal office. In August 1844, the county commissioners took Wright's offer of 50 acres and made Paris the county seat.

The area of present Lamar County was part of Red River County during the Republic of Texas. By 1840 population growth had demanded organization of a new county. Wright, who had served in the Third Congress as a representative from Red River County, was a major promoter of the founding of Lamar County, which was established by act of the Fifth Congress of the Republic on December 17, 1840. It was organized by elections held on February 1, 1841. The county included much of what would become Delta County in 1870, which then reduced Lamar County to its present size.

The original county seat was Lafayette, a small settlement located several miles northwest of the site of present-day Paris. On June 22, 1841, forty acres of land was donated by John Watson to build a new county seat. The town was platted, no lots were ever sold, and the county court continued to meet at Lafayette. In 1842 the Texas Congress passed a law requiring each county seat to be located within five miles of the geographic center of the county. Accordingly, Mount Vernon was made Lamar county seat in 1843, but no courthouse was ever built.

The following year, George Wright offered to donate fifty acres for a town, if the county commissioners would make it the county seat. The commissioners was accepted, and the town was named Paris. The first term of the county court was held there on April 29, 1844.

The first recorded settlers in the area came in 1826, although settlers were known to have been in the area as early as 1824. It was incorporated by the Congress of the Republic of Texas on February 3, 1845. Paris was on the Central National Road of the Republic of Texas, which went from San Antonio through Paris to cross the Red River. By the time of Civil War, when Paris had 700 residents, the town had become a cattle and farming center. It is the site of the first municipally owned and operated abattoir in the United States. In 1861 Lamar County was one of the few Texas counties to vote against secession, though many of its citizens would serve in the Confederate Army.

In 1893 Henry Smith, a black teenager, was accused of murder and lynched by a white mob in a racially motivated act. Thousands of people watched him be "tortured and burned to death on a scaffold."[3]

In 1877, 1896, and 1916, major fires in the city forced considerable rebuilding. The 1916 fire was so extensive that it destroyed almost half the town, ruining most of the central business district and sweeping through a residential area before it was finally controlled, resulting in property damages estimated at $11 million. Burned structures included the Federal Building and Post Office, Lamar County Courthouse and Jail, City Hall, most commercial buildings, and several churches.[4] The 1916 fire started around 5 p.m. on March 21, 1916. The exact cause of the fire is unknown. Winds estimated at 50 miles per hour fanned the flames that were visible for up to forty miles away. The fire was brought under control on the morning on March 22 by local firefighters and those from surrounding cities in Texas and Hugo, Oklahoma.

In 1920 the two Arthur brothers, also black, were lynched at the county fairgrounds in Paris. They were tied to a flagpole and then burned. The city has numerous monuments related to the Confederacy, but no acknowledgement of these acts of racial terrorism.[3]

In 1943, the U.S. Supreme Court struck down a Paris law requiring permits to take order for books in Largent v. Texas. The court found the law's intent was to violate the free speech rights of Jehovah's Witnesses.

The film Paris, Texas (1984) by German director Wim Wenders was named after the city, but was not set there.

Eiffel Tower replica

Fifteen American municipalities are named "Paris;" many have erected replicas of the Eiffel Tower to pay homage to the city in Paris, France.

Both Paris of Texas and Paris, Tennessee built Eiffel Tower replicas in 1993: Tennessee's was built at Christian Brothers University (in Memphis) and was 60 feet tall; the one in Texas was built by the Boilermakers 902, a labor union representing workers of the former Babcock & Wilcox Paris Plant, and was 65 feet tall. In 1998 when Tennessee moved its tower to their city of Paris, they heightened it to 70 feet.

Paris, Texas, made the claim of being "The second largest Paris in the World." In 1998 town boosters added a large red cowboy hat to the top of the tower, making it taller than Tennessee's tower.

However, in 1999, Las Vegas erected a 540-foot-tall Eiffel Tower replica along the Strip. At half the height of the original (which is 984 feet tall), this Eiffel Tower is nearly ten times taller than the other replicas.

Transportation

Paris has long been a railroad center. The Texas and Pacific reached town in 1876; the Gulf, Colorado and Santa Fe Railway (later merged into the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway) and the St. Louis - San Francisco Railway in 1887; the Texas Midland (later Southern Pacific) in 1894; and the Paris and Mount Pleasant (Pa-Ma Line) in 1910.

Historical residences

.jpg)

The city is home to several stately late 19th century to mid-20th century homes. Among these is the Rufus Fenner Scott Mansion, designed by German architect J.L. Wees and constructed in 1910. The structure is solid concrete and steel with four floors. Rufus Scott was a prominent businessman known for shipping, imports, and banking. He was well known by local farmers who bought aging transport mules from him. The Scott Mansion narrowly survived the fire of 1916. After the fire, Scott brought the architect Wees back to Paris to redesign the historic downtown area.[5]

In the early 1930s, Rufus Scott died, and his property was purchased by Gene Roden, who converted the house to a funeral home. It was the first funeral home in northeast Texas to have its own chapel. The site was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1982. On April 1, 2006, Gene Roden's Sons Funeral Home was sold to Arvin Starrett and E. Casey Rose (who was managing the firm at the time) and the name was changed to Starrett-Rose Funeral Home. In March 2007, Casey Rose sold his 50% interest in the firm to Arvin Starrett and the name became Starrett Funeral Home.

The recently restored home of William Belford Wise was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1988. The property is an example of late Victorian Queen Anne style architecture in masonry.

Paris Junior College

.jpg)

Paris Junior College was established in 1924. In 1990, it was one of the oldest junior colleges in Texas. Its main campus had 20 buildings, including a new $1.1 million physical education center, and the college offered both technical and academic instruction.

Its jewelry technologies department, now known as The Texas Institute of Jewelry Technology at Paris Junior College, is internationally recognized as one of the premier jewelry schools in the world.

Paris Junior College Dragon's Men's basketball team won the NJCAA national championship in 2005. During the 1960s through the 1980s, the school boasted nationally ranked men's Tennis programs. Paris Junior College has a new women's dormitory that opened up in fall of 2012, along with a new multimillion Science and Mathematics building that opened in the spring of 2013. The college has three campuses in Texas: the main one in Paris, a large campus in Sulphur Springs, and another in Greenville. Enrollment was expected to surpass 5,000 students in 2013.

Camp Maxey

From 1942 to 1945, the US Army operated Camp Maxey, 10 miles (16 km) north of Paris. During World War II, Camp Maxey had an area of 36,683 Acres (14,845.08 Hectares), and billeting space for 2,022 Officers, and 42,515 Enlisted Personnel.

The camp served as an infantry-division training camp. It was named in honor of Samuel Bell Maxey, a Major General for the Confederacy in the American Civil War and later elected from Texas to the U.S. Senate. The camp was activated on 15 July 1942 and deactivated 1 October 1945. It also served as an internment center for many German prisoners of war.

In the 21st century, Camp Maxey is maintained by a Texas Army National Guard unit,[6] who regularly conduct training exercises. The Camp is garrisoned normally by a force of 10 men. Civil Air Patrol's Texas Wing also regularly uses the camp for training events.

In June 2008, when word came that over 600 American service personnel were coming to receive training for the war in Iraq, residents of the city of Paris adopted them. They donated what they thought the troops would need in order to enjoy their time in Paris before being sent to the war.

City rating

Paris, Texas was named "Best Small Town in Texas" by Kevin Heubusch in his book The New Rating Guide to Life in America's Small Cities (1997).[7]

Media

Newspaper

Since 1869, The Paris News has served as the newspaper in the city of Paris. It circulates daily in the city and throughout Lamar County as well as in neighboring Delta County, Fannin County, Red River County and Choctaw County, Oklahoma.

Radio stations

Five radio stations are licensed in the city of Paris: KZHN, KPLT (AM), KOYN, KBUS, KPLT-FM.

Television

Paris is served by KXII, the low-power translator station KXIP-LD (channel 12) is in Paris.

Race relations

Paris is deeply segregated.[8] Race relations in Paris have been accompanied by severe terrorist violence of whites against blacks. They have been deeply polarized,[9] turbulent,[10] and sometimes explosive.[10]

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, whites conducted several lynchings of black men at the Paris Fairgrounds as public spectacles. Thousands of white spectators cheered as the victims were tortured and burned, dismembered, or otherwise murdered.[8][9] Among the victims were Henry Smith, a teenager lynched in 1893. In 1920 two Arthur brothers were killed together.

115 years later, in 2008, Brandon McClelland, an African-American man, was run over and dragged to death under a vehicle. Two white men were arrested, but the prosecutor cited lack of evidence and declined to press charges. There was no serious attempt to investigate or find the perpetrators. African Americans in Paris were outraged and disappointed. Brenda Cherry, Paris resident and founder of Concerned Citizens for Racial Equality, opined:

I think we are probably stuck in 1930 right about now.[11]

Lamar County Judge M. C. Superville disagreed, saying:

I do not believe there is systematic racial discrimination in Lamar County. I do believe there is a misperception that that is going on.[11]

The United States Department of Justice Justice Community Relations Service worked to initiate a dialog between the races in the town.[12] It was considered a failure when African-American complaints were met mostly by silent glares by whites.[9] A 2009 protest rally over the McClelland case led to Texas State Police intervention to prevent ethnic groups from coming to blows.[13]

In 2007, a 14-year-old African-American girl was sentenced by a local judge to up to 7 years in a youth prison for shoving a hall monitor at Paris High School. Three months earlier, the same judge had sentenced a 14-year-old white girl to probation for an act of arson. This sentencing disparity for actions of such different scale generated nationwide controversy and outrage.[14] On orders of a special conservator, appointed by the State of Texas to investigate problems with the state's juvenile justice practices, the African-American girl was released after serving one year.[14]

In 2009, some African-American workers at the Turner Industries plant in the city claimed that hangman's nooses, Confederate flags and racist graffiti were regular features of plant culture.[15] At the same time, the United States Department of Education was conducting an investigation into allegations that African-American students in Paris's schools were disciplined more harshly than white students for similar offenses.[14]

In 2015, the United States Equal Employment Opportunity Commission ruled after an investigation that African-American workers at the Sara Lee Corporation plant in Paris (closed in 2011)[16] were disproportionately exposed to hazards of asbestos, black mold, and other toxins. It said that they were targets of racial slurs and racist graffiti.[17] Some Paris residents deny that the town has a race relations problem.[8][13][11]

Geography

Paris is located at 33°39′45″N 95°32′52″W / 33.66250°N 95.54778°W (33.662508, −95.547692).[18] According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 44.4 square miles (115 km2), of which 42.8 square miles (111 km2) is land and 1.7 square miles (4.4 km2) (3.74%) is water.

Climate

Paris has a humid subtropical climate (Cfa in the Koeppen climate classification). It is located in "Tornado Alley", an area largely centered in the middle of the United States in which tornadoes occur frequently because of weather patterns and geography. Paris is in USDA plant hardiness zone 8a for winter temperatures. This is cooler than its southern neighbor Dallas, and while similar to Atlanta, Georgia, it has warmer summertime temperatures. Summertime average highs reach 94 F and 95 °F (35 °C) in July and August, with associated lows of 72 and 71. Winter temperatures drop to an average high of 51 and low of 30 in January. The highest temperature on record was 115, set in August 1936, and the record low was −5, set in 1930. Average precipitation is 47.82 inches (1,215 mm). Snow is not unusual, but is by no means predictable, and years can pass with no snowfall at all.

On April 2, 1982, Paris was hit by an F4 tornado that destroyed more than 1,500 homes, left ten people dead, 170 injured and 3,000 homeless. The damage toll from this tornado was estimated at 50 million USD in 1982.[19]

| Climate data for Paris, Texas | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °F (°C) | 51 (11) |

56 (13) |

65 (18) |

75 (24) |

82 (28) |

89 (32) |

94 (34) |

94 (34) |

87 (31) |

77 (25) |

65 (18) |

54 (12) |

74.1 (23.3) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 30 (−1) |

34 (1) |

44 (7) |

53 (12) |

61 (16) |

69 (21) |

73 (23) |

72 (22) |

65 (18) |

53 (12) |

43 (6) |

33 (1) |

52.5 (11.5) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 2.2 (56) |

3.2 (81) |

4.2 (107) |

4.0 (102) |

5.9 (150) |

3.9 (99) |

3.6 (91) |

2.7 (69) |

4.8 (122) |

4.6 (117) |

3.9 (99) |

3.3 (84) |

46.1 (1,171) |

| Source: [20] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1880 | 3,980 | — | |

| 1890 | 8,254 | 107.4% | |

| 1900 | 9,358 | 13.4% | |

| 1910 | 11,269 | 20.4% | |

| 1920 | 15,040 | 33.5% | |

| 1930 | 15,649 | 4.0% | |

| 1940 | 18,678 | 19.4% | |

| 1950 | 21,643 | 15.9% | |

| 1960 | 20,977 | −3.1% | |

| 1970 | 23,441 | 11.7% | |

| 1980 | 25,498 | 8.8% | |

| 1990 | 24,799 | −2.7% | |

| 2000 | 25,898 | 4.4% | |

| 2010 | 25,171 | −2.8% | |

| Est. 2015 | 24,782 | [21] | −1.5% |

| Texas Almanac[22] | |||

As of the 2010 United States Census, there were 25,171 people.[23] As of the census[24] of 2000, there were 25,898 people, 10,570 households, and 6,711 families residing in the city. The population density was 605.7 people per square mile (233.9/km²). There were 11,777 housing units at an average density of 275.5 per square mile (106.4/km²). The racial makeup of the city was 72.92% White, 22.26% African American, 0.95% Native American, 0.66% Asian, 0.03% Pacific Islander, 1.56% from other races, and 1.63% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 4.12% of the population.

There were 10,570 households, of which 29.4% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 42.7% were married couples living together, 17.0% had a female householder with no husband present, and 36.5% are classified as non-families by the United States Census Bureau. Of 10,570 households, 385 are unmarried partner households: 349 heterosexual, 14 same-sex male, and 22 same-sex female households. 32.5% of all households were made up of individuals and 15.2% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.35 and the average family size was 2.97.

In the city the population was spread out with 25.4% under the age of 18, 10.0% from 18 to 24, 25.8% from 25 to 44, 20.9% from 45 to 64, and 18.0% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 36 years. For every 100 females there were 86.1 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 80.6 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $27,438, and the median income for a family was $34,916. Males had a median income of $29,378 versus $20,080 for females. The per capita income for the city was $17,137. About 16.5% of families and 20.6% of the population were below the poverty line, including 29.0% of those under age 18 and 15.9% of those age 65 or over.

Economy

In the past, Paris was a major cotton exchange, and the county was developed as cotton plantations. While cotton is still farmed on the lands around Paris, it is no longer a major part of the economy.

Paris' one major hospital has two campuses: Paris Regional Medical Center South (formerly St. Joseph's Hospital) and Paris Regional Medical Center North (formerly McCuistion Regional Medical Center). It serves as center for healthcare for much of Northeast Texas and Southeast Oklahoma. Both campuses are now operated jointly under the name of the Paris Regional Medical Center, a division of Essent Healthcare. The health network is the largest employer in the Paris area.

Outside of healthcare, the largest employers are Kimberly-Clark, and Campbell's Soup.

| # | Employer | # of Employees |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Essent-PRMC | 1000 |

| 2 | Campbell Soup | 900 |

| 3 | Kimberly-Clark | 800 |

| 4 | Turner Industries | 700 |

| 5 | Paris ISD | 640 |

| T-6 | North Lamar ISD | 500 |

| T-6 | Walmart | 500 |

| 8 | TCIM | 480 |

| 9 | City of Paris | 320 |

| 10 | We-Pack Logistics | 300 |

Note: PRMC is Paris Regional Medical Center

Education

.jpg)

Elementary and secondary education is split among three main school districts:

- The Paris Independent School District

- The North Lamar Independent School District

- The Chisum Independent School District

Prairiland ISD also serves a small portion of the town along with Blossom ISD, as well as Clarksville and Roxton ISD, respectively.

In addition, Paris Junior College provides post-secondary education. It hosts the Texas Institute of Jewelry Technology, a well-respected school of gemology, horology, and jewelry. The Industrial Technology Division offers programs in Air Conditioning Technology, Refrigeration Technology, Agricultural Technology, Drafting and Computer-aided Design, Electronics, Electromechanical Technology, and Welding Technology.

Texas A&M University-Commerce, a major university of over 12,000 students, is located in the neighboring city of Commerce, 40 minutes southwest of Paris.

The Paris Public Library serves Paris.[26]

Government

.jpg)

It is governed by a city council as specified in the city's charter adopted in 1948.

State government

Paris is represented in the Texas Senate by Republican Kevin Eltife, District 1, and in the Texas House of Representatives by Republican Erwin Cain, District 3.

The Texas Department of Criminal Justice (TDCJ) operates the Paris District Parole Office in Paris.[27]

Federal government

At the Federal level, the two U.S. Senators from Texas are Republicans John Cornyn and Ted Cruz. Paris is part of Texas congressional 4th district, represented by Republican John Ratcliffe.

The United States Postal Service operates the Paris Post Office.[28]

Transportation

Major highways

According to the Texas Transportation Commission, Paris is the second-largest city in Texas without a four-lane divided highway connecting to an Interstate highway within the state. However, those traveling north of the city can go into the Midwest on a four-lane thoroughfare via US 271 across the Red River into Oklahoma, and then the Indian Nation Turnpike from Hugo to Interstate 40 at Henryetta, which in turn continues as a free four-lane highway via US 75 to Tulsa.

Paris is served by two taxicab companies. Cox Field provides general aviation services.

Attractions

- Pat Mayse Lake

- Lake Crook

- St. Paul Baptist Church - Founded in 1867 by former slave Elijah Barnes, it was among independent black Baptist congregations which freedmen quickly set up after the Civil War. Most of them left the Southern Baptist Convention, creating their own associations. This is registered at the state and federal level as the second-oldest African-American Baptist church in the state. The current pastor is Kenneth Rogers.

- Central Presbyterian Church – Founded in 1844, it was the first church formed in Lamar County. It has historic stained glass windows and is historically registered at the state and federal levels

- Beaver's Bend Resort Park (Oklahoma)

- Evergreen Cemetery – Located on the south side of town, there are over 50,000 people interred. This is the site of a noted 12-foot (3.7 m) tall "Jesus with cowboy boots" statue and grave marker, as well as the resting place of banker/philanthropist William J. McDonald, Confederate General/U.S. Senator Sam Bell Maxey, rancher Pitts Chisum, and cotton magnate John J. Culbertson. Pitts Chisum's more famous brother, John Chisum, is also buried in the city.

- Sam Bell Maxey House – Maxey was a planter and Confederate general

- Culbertson Fountain

- Bywaters Park

- Pine Branch Daylily Farm – Breeding and selling of over 1,000 registered varieties.

- Paris Eiffel Tower

- Restored County Courthouse and its lawn with monuments

- Downtown restored 1918 period buildings

- Trail de Paris – multi-use recreational facility along abandoned railroad corridor

- Record Park

- Public Pool & Bath House

- The second Saturday of every October amateur radio enthusiasts (ham radio operators) come to the city in large numbers to attend the annual Paris, Texas Hamfest.

- On October 4, 1955, early in his career, Elvis Presley performed at the Boys Club Gymnasium at 1530 1st Street Northeast in Paris as a member of the Louisiana Hayride Jamboree tour.

- Annual Paris Art Fair sponsored by the YWCA Paris and Lamar County.

- Each July the Tour de Paris, a bicycle tour that brings many tourists, both American and European.

- Lamar County Historical Museum

Notable people

- Duane Allen, member of The Oak Ridge Boys

- Tia Ballard, actress for Funimation Entertainment

- Charles Baxter, physician, attended President Kennedy after shot

- Raymond Berry, professional football Hall of Famer

- Brenda Cherry, civil rights activist

- John Chisum, cattle baron

- Marsha Farney, Republican member of the Texas House of Representatives from Williamson County; reared in Paris, graduated from Paris Junior College, and taught school in Paris in 1990s

- Bobby Jack Floyd, National Football League fullback

- Charles R. Floyd, three-term Democratic state senator; pioneer of the Texas Farm-to-market road system and an original founder of Paris Junior College

- Cas Haley, singer/musician, NBC's Season 2 of America's Got Talent runner-up

- William Henry Huddle, Texas Capitol artist

- Charlie Jackson, football player

- Frank Jackson, football player

- General John P. Jumper, Chief of Staff of the United States Air Force from 2001 to 2005

- Horace Ladymon, department store owner, Beall-Ladymon; born in Paris in 1929; resides in Shreveport, Louisiana

- Beverly Leech, actress, portrayed Kate Monday on Mathnet

- Samuel Bell Maxey, United States Senator and Confederate Major General

- Gordon McLendon, pioneer radio broadcaster and founder of the Liberty Broadcasting System

- Jay Hunter Morris, operatic tenor

- John Osteen, pastor

- Dave Philley, professional baseball player and holder of five MLB records

- Bass Reeves, Deputy U.S. Marshal

- Admiral James O. Richardson, United States Navy Fleet Commander 1940–1941

- Eddie Robinson, professional baseball player, four-time All-Star and Texas Rangers executive

- Jack Russell, professional baseball player and first relief pitcher selected to a Major League Baseball All-Star Game

- Leslie Satcher, country music recording artist

- William Scott Scudder, Major League Baseball pitcher

- Gene Stallings, Alabama head coach 1990-1996

- Steven H. Tallant, president of Texas A&M University-Kingsville

- Starke Taylor, Mayor of Dallas and businessman

- Shangela Laquifa Wadley, comedian, reality television personality

References

- ↑ "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. 2007-10-25. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- ↑ "Physiographic Regions". Tapestry.usgs.gov. 2003-04-17. Retrieved 2011-11-20.

- 1 2 CAMPBELL ROBERTS, "History of Lynchings in the South Documents Nearly 4,000 Names", New York Times, 10 February 2015; accessed 19 August 2016

- ↑ Tx State Historical Commission (1978). "The Paris Fire of 1916 – Texas State Historical Marker".

- ↑ Tx State Historical Commission (1984). "Scott Mansion – Texas State Historical Marker".

- ↑ Camp Maxey, globalsecurity.org.

- ↑ The New Rating Guide to Life in America's Small Cities. Prometheus Books. 1997. ISBN 978-1573921701. cited in Day Trips from Dallas/Fort Worth: Getaway Ideas for the Local Traveler. Day Trips. GPP Travel. 2010. p. 42. ISBN 978-0762757077. Retrieved May 1, 2015.

- 1 2 3 Howard Witt (March 12, 2007). "To some in Paris, sinister past is back". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved May 1, 2015.

- 1 2 3 Howard Witt (February 1, 2009). "Paris, Texas, race relations dialogue turns into dispute". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved May 1, 2015.

- 1 2 Gretel C. Kovach; Ariel Campo–Flores (July 27, 2009). "The turbulent racial history of Paris, Texas". Newsweek, via Anderson Cooper 360°. CNN. Retrieved May 1, 2015.

- 1 2 3 James C. McKinley Jr. (February 14, 2009). "Killing Stirs Racial Unease in Texas". New York Times. Retrieved May 3, 2015.

- ↑ Richard Abshire (December 4, 2008). "Justice Department community dialogue on race set for Paris, Texas". Crime Blog. Dallas Morning News. Retrieved May 1, 2015.

- 1 2 Jeff Carlton (August 21, 2009). "Riot Police Storm Texas Town After Black, White Protesters Clash Over Dragging Death". Huffington Post. Retrieved May 3, 2015.

- 1 2 3 Howard Witt (March 31, 2007). "Girl in prison for shove gets released early". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved May 5, 2015.

- ↑ Howard Witt (February 25, 2009). "Racism bedevils Texas town". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved May 5, 2015.

- ↑ Alejandra Cancino (February 10, 2015). "Sara Lee discriminated against black employees, attorneys say". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved May 3, 2015.

- ↑ "Workers Targets of Racist Behavior at Sara Lee Plant: EEOC". NBC Channel 5 Dallas–Fort Worth. February 10, 2015. Retrieved May 3, 2015.

- ↑ "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. 2011-02-12. Retrieved 2011-04-23.

- ↑ Boyd, Matthew. "Paris officers remember deadly tornado of 1982". Retrieved 2016-10-27.

- ↑ "Weatherbase". Weatherbase. Retrieved 2011-11-20.

- ↑ "Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for Incorporated Places: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2015". Retrieved July 2, 2016.

- ↑ "PARIS". Texas Almanac. Retrieved 2013-08-26.

- ↑ "American FactFinder". Factfinder2.census.gov. 2010-10-05. Retrieved 2011-11-20.

- ↑ "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- ↑ http://gfoa.net/cafr/COA2011/ParisTX.pdf

- ↑ Paris Public Library

- ↑ Parole Division Region I of the Texas Department of Criminal Justice.

- ↑ Post Office Location – Paris

External links

![]() Media related to Paris, Texas at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Paris, Texas at Wikimedia Commons

| Wikisource has the text of The New Student's Reference Work article Paris, Tex.. |

- City of Paris

- Paris Texas Event Calendar

- Lamar County Historical Society

- Lamar County Courthouse

- Handbook of Texas Online entry

- Paris Texas information – Lamar County Station

Coordinates: 33°39′45″N 95°32′52″W / 33.662508°N 95.547692°W