Pan-European identity

| European Union |

This article is part of a series on the |

Policies and issues

|

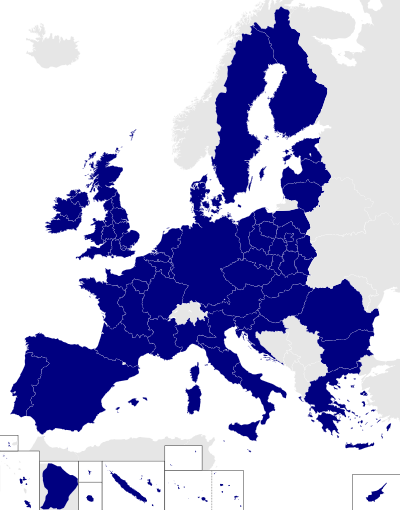

Pan-European identity is the sense of personal identification with Europe. The most concrete example of pan-Europeanism is the European Union (EU). 'Europe' is widely used as a synonym for the EU, as 500 million Europeans (70%) are EU citizens; however, many nations that are not part of the EU may have large portions of their populations who identify themselves as European as well as their country nationality. Those countries are usually part of the older Council of Europe and have aspirations of EU membership. The prefix pan implies that the identity applies throughout Europe, and especially in an EU context, 'pan-European' is often contrasted with national.

The related concept Europeanism is the assertion that the people of Europe have a distinctive set of political, economic and social norms and values that are slowly diminishing and replacing existing national or state-based norms and values.[1]

Historically, European culture has not led to a geopolitical unit. As with the constructed nation, it might well be the case that a political or state entity will have to prefigure the creation of a broad, collective identity.[2] At present, European integration co-exists with national loyalties and national patriotism.[3]

A development of European identity is regarded by supporters of European integration as part of the pursuit of a politically, economically and militarily influential united Europe.[4] Such proponents argue it supports the foundations of common European values, such as of fundamental human rights and spread of welfare,[4] and strengthens the supra-national democratic and social institutions of the European Union.[5] The concept of common European identity is viewed as rather a by-product than the main goal of the European integration process, and is actively promoted by both EU bodies and non-governmental initiatives.[4] Eurosceptics tend to oppose such a concept, preferring national identities of the various nation states of the European continent.

History

A sense of European identity traditionally derives from the idea of a common European historical narrative. In turn, that is assumed to be the source of the most fundamental European values. Typically the 'common history' includes a combination of Ancient Greece and Ancient Rome, the feudalism of the Middle Ages, the Hanseatic League, the Renaissance, the Age of Enlightenment, 19th century liberalism and different forms of socialism, Christianity and secularism, colonialism and the World Wars.

Nowadays, European identity is promoted by, among others, the European Commission, and especially their Directorate-General for Education and Culture. They promote this identity and ideology through funding of educational exchange programmes, the renovation of key historical sites, the promulgation of a progressive linear history of Europe terminating in European integration, and through the promotion and encouragement of political integration.

The oldest European unification movement is the Paneuropean Union, founded in 1923 with the publishment of Richard Nikolaus von Coudenhove-Kalergi's book Paneuropa, who also became its first president (1926-1972), followed by Otto von Habsburg (1973-2004) and Alain Terrenoire (2004-). Although this movement did not succeed in preventing the outbreak of the Second World War because of the Wall Street Crash of 1929 and the rise of totalitarian regimes, it led the European nations to the peaceful integration process after the war that resulted in the formation of the European Union. Fathers of the European Union were convinced Paneuropeans, such as Konrad Adenauer, Robert Schuman and Alcide De Gasperi. The movement is today still very active in promoting the European identity and common European values, the principles of solidarity and subsidiarity as well as the political, economic and cultural integration of Europe.

Popular culture

The common cultural heritage is commonly seen in terms of high culture. Examples of a contemporary pan-European culture are limited to some forms of popular culture:

The Eurovision Song Contest is one of the oldest identifiably 'pan-European' elements in popular culture,[6] attracting a huge audience (hundreds of millions) and extensive media coverage each year, with the higher-scoring songs often making an impact in national singles charts. The contest is not run by the EU, but by the entirely separate European Broadcasting Union, and in fact it pre-dates the European Economic Community. It is also open to some non-European countries which are members of the EBU. Some eastern European politicians occasionally take the contest more seriously, seeing the participation of their country as a sign of 'belonging to Europe', and some even going so far to say to consider it a preliminary step to accession to the EU.[7]

The European Film Awards are presented annually since 1988 by the European Film Academy to recognize excellence in European cinematic achievements. The awards are given in over ten categories of which the most important is the Film of the year. They are restricted to European cinema and European producers, directors, and actors.[8]

Deliberate attempts to use popular culture to promote identification with the EU have been controversial. In 1997, the European Commission distributed a comic strip titled The Raspberry Ice Cream War, aimed at children in schools. The EU office in London declined to distribute this in the UK, due to an expected unsympathetic reception for such views.[9][10]

Captain Euro, a cartoon character superhero mascot of Europe, was developed in the 1990s by branding strategist Nicolas De Santis to support the launch of the Euro currency.[11][12][13] In 2014, London branding think tank, Gold Mercury International, launched the Brand EU Centre, with the purpose of solving Europe’s identity crisis and creating a strong brand of Europe.[14][15]

Sport

Almost all sport in Europe is organised on either a national or sub-national basis. 'European teams' are rare, one example being the Ryder Cup, a Europe vs. United States golf tournament. There have been proposals to create a European Olympic Team, which would break with the existing organisation through National Olympic Committees.[16] Former European Commission President Romano Prodi suggested that EU teams should carry the EU flag, alongside the national flag, at the 2008 Summer Olympics – a proposal which angered eurosceptics.[17][18] According to Eurobarometer surveys, only 5% of respondents think that a European Olympic team would make them feel more of a 'European citizen'.[19]

National teams participate in international competitions, organised by international sport federations, which often have a European section. That results in a hierarchic system of sporting events: national, European, and global. In some cases, the competition has a more 'pan-European' character. Football – Europe's most popular sport – is organised globally by FIFA, and in Europe by UEFA. Alongside the traditional national/international organisation, direct competition between major teams at pan-European level has become more important. (High national ranking is necessary to enter the UEFA Champions League and the UEFA Europa League). Super-clubs such as Real Madrid CF, F.C. Barcelona, FC Bayern Munich, Liverpool F.C., Arsenal F.C., Manchester United F.C., A.C. Milan, Juventus F.C., Inter Milan, S.L. Benfica, F.C. Porto, AFC Ajax are known all over Europe, and are seen as each other's competitors, in UEFA's European tournaments. (Major clubs are now large businesses in themselves, and have expanded beyond the national sponsoring market).

Symbols

The following symbols are used mainly by the European Union:

- A flag, the European flag – officially used by the European Union along with other inter-European institutions.

- An anthem, "Ode to Joy" – national anthem for all Council of Europe members and the European Union.

- A national day, Europe day (9 May) – as for the flag and the anthem.

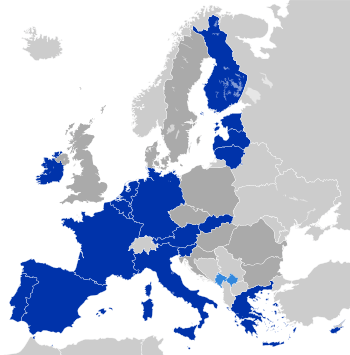

- A single currency, the euro – the euro has been adopted by some countries outside of the EU, but not by all EU member states in the bloc. As of 2015, 19 of 28 member states have adopted the euro as their official currency. Most EU members will have to adopt the Euro when their economies meet the criteria; however, the United Kingdom and Denmark have opt-out agreements.

- Vehicle registration plates mostly share the same common EU design since 1998.

- Driving licences have shared a single common design from 1980 to 2013, and since 2013 there is a unique, plastic credit card-like design inside the EU.

- EU citizenship gives the right to every EU citizen to move, reside and work freely within the territory of any EU member states.

- EU member states use a common passport design, burgundy coloured with the name of the member state, Coat of Arms and the title "European Union" (or its translation).

- The European Health Insurance Card extends the area of free basic healthcare availability to the EU countries for those who are nationally insured in their country.

- The Schengen Area allows the citizens of the signing members to travel from any of their countries to each other without the need of passport.

- Other: Erasmus Programme, European registration numbers, separate EU corridor at airports[4]

The .eu domain name extension was introduced in 2005 as a new symbol of European Union identity on the World Wide Web. The .eu domain's introduction campaign specifically uses the tagline "Your European Identity" . Registrants must be located within the European Union.

See also

- Brand EU

- Captain Euro

- Continentalism

- Eurocentrism

- European Dream

- Paneuropean Union

- European integration

- European symbols

- Europeanisation

- Europeanism

- Euroscepticism

- Europatriotism

- Federal Europe

- Potential Superpowers – European Union

- Pre-1945 ideas on European unity

- Pro-Europeanism

- Proto-Indo-European language

References

- ↑ John McCormick, Europeanism (Oxford University Press, 2010)

- ↑ Ernest Gellner, Nations and Nationalism, 1983

- ↑ "The supranational prospect held out by the EU appears to be threatened.... by a deficiency of European identity, in striking contrast to the continuing vigour of national identities, ...." Anne-Marie Thiesse. Inventing national identity.

- 1 2 3 4 European identity: construct, fact and fiction Dirk Jacobs and Robert Maier Utrecht University

- ↑ "Crowdfunding and Civic Society in Europe: A Profitable Partnership?". Open Citizenship Journal. Retrieved April 29, 2013.

- ↑ "Eurovision is something of a cultural rite in Europe."

- ↑ "We are no longer knocking at Europe’s door," declared the Estonian Prime Minister after his country’s victory in 2001. "We are walking through it singing... The Turks saw their win in 2003 as a harbinger of entry into the EU, and after the Orange Revolution in Ukraine, tonight’s competition is a powerful symbol of Viktor Yushchenko’s pro-European inclinations." Oj, oj, oj! It's Europe in harmony. The Times, 21 May 2005. ""This contest is a serious step for Ukraine towards the EU," Deputy Prime Minister Mykola Tomenko said at the official opening of the competition." BBC, Ukrainian hosts' high hopes for Eurovision

- ↑ http://www.europeanfilmawards.eu/

- ↑ Archived 11 February 2006 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Captain Euro". The Yes Men. Retrieved 28 March 2013.

- ↑ Designweek, 19 February 1998. Holy Bureaucrat! It's Captain Euro! Retrieved 11 June 2014. http://www.designweek.co.uk/news/holy-bureaucrat-its-captain-euro/1120069.article

- ↑ Wall Street Journal, 14 December 1998. Captain Euro will teach children about the Euro, but foes abound. Retrieved 11 June 2014. http://online.wsj.com/news/articles/SB913591261156420500

- ↑ Kidscreen, 1 March 1999. New Euro hero available for hire. Retrieved 11 June 2014. http://kidscreen.com/1999/03/01/24620-19990301/

- ↑ Designweek, Angus Montgomery, 29 May 2014. Is it time to rebrand the EU? Retrieved 11 June 2014. http://www.designweek.co.uk/analysis/is-it-time-to-rebrand-the-eu/3038521.article

- ↑ CNBC, Alice Tidey, 19 May 2014. The EU's main problem? Its brand! Retrieved 11 June 2014. http://www.cnbc.com/id/101667358

- ↑ "European Olympic Team". Archived from the original on 31 March 2006. Retrieved 7 February 2006.

- ↑ Cendrowicz, Leo (1 March 2007). "United in Europe" (PDF). European Voice: 12. Retrieved 28 March 2013.

- ↑ "Olympics: Prodi wants to see EU flag next to national flags". EurActiv. Retrieved 28 March 2013.

- ↑ Eurobarometer 251, p 45, .