Palm oil

Palm oil (also known as dendê oil, from Portuguese) is an edible vegetable oil derived from the mesocarp (reddish pulp) of the fruit of the oil palms, primarily the African oil palm Elaeis guineensis,[1] and to a lesser extent from the American oil palm Elaeis oleifera and the maripa palm Attalea maripa.

Palm oil is naturally reddish in color because of a high beta-carotene content. It is not to be confused with palm kernel oil derived from the kernel of the same fruit,[2] or coconut oil derived from the kernel of the coconut palm (Cocos nucifera). The differences are in color (raw palm kernel oil lacks carotenoids and is not red), and in saturated fat content: palm mesocarp oil is 41% saturated, while palm kernel oil and coconut oil are 81% and 86% saturated fats, respectively.

Along with coconut oil, palm oil is one of the few highly saturated vegetable fats and is semisolid at room temperature.[3]

Palm oil is a common cooking ingredient in the tropical belt of Africa, Southeast Asia and parts of Brazil. Its use in the commercial food industry in other parts of the world is widespread because of its lower cost[4] and the high oxidative stability (saturation) of the refined product when used for frying.[5][6]

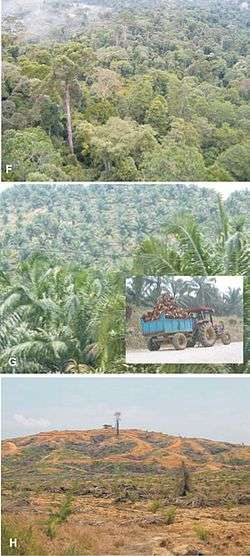

The use of palm oil in food products has attracted the concern of environmental activist groups; the high oil yield of the trees has encouraged wider cultivation, leading to the clearing of forests in parts of Indonesia and Malaysia to make space for oil-palm monoculture.[7] This has resulted in significant acreage losses of the natural habitat of the orangutan, of which both species are endangered; one species in particular, the Sumatran orangutan, has been listed as critically endangered.[8] In 2004, an industry group called the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil was formed to work with the palm oil industry to address these concerns.[9] Additionally, in 1992, in response to concerns about deforestation, the Government of Malaysia pledged to limit the expansion of palm oil plantations by retaining a minimum of half the nation's land as forest cover.[10][11]

History

Human use of oil palms may date as far back as 5,000 years; in the late 1800s, archaeologists discovered a substance that they concluded was originally palm oil in a tomb at Abydos dating back to 3,000 BCE.[12] It is believed that Arab traders brought the oil palm to Egypt.[13] Some argue that it is not possible that Arab traders could have brought the oil palm to ancient Egypt, as the Arabs did not settle in Africa until the 8th century CE. It is more likely that the oil palm was brought to Ancient Egypt (Kemet) by its founding peoples who migrated from other regions of the African continent.[14]

Palm oil from E. guineensiss has long been recognized in West and Central African countries, and is widely used as a cooking oil. European merchants trading with West Africa occasionally purchased palm oil for use as a cooking oil in Europe.

Palm oil became a highly sought-after commodity by British traders, for use as an industrial lubricant for machinery during Britain's Industrial Revolution.[15]

Palm oil formed the basis of soap products, such as Lever Brothers' (now Unilever) "Sunlight" soap, and the American Palmolive brand.[16]

By around 1870, palm oil constituted the primary export of some West African countries, such as Ghana and Nigeria, although this was overtaken by cocoa in the 1880s.

Composition

Fatty acids

Palm oil, like all fats, is composed of fatty acids, esterified with glycerol. Palm oil has an especially high concentration of saturated fat, specifically, of the 16-carbon saturated fatty acid palmitic acid, to which it gives its name. Monounsaturated oleic acid is also a major constituent of palm oil. Unrefined palm oil is a significant source of tocotrienol, part of the vitamin E family.[17][18]

The approximate concentration of fatty acids in palm oil is:[19]

Carotenes

Red palm oil is rich in carotenes, such as alpha-carotene, beta-carotene and lycopene, which give it a characteristic dark red color.[18][20]

Processing and use

Many processed foods either contain palm oil or various ingredients derived from it.[21]

Refining

After milling, various palm oil products are made using refining processes. First is fractionation, with crystallization and separation processes to obtain solid (stearin), and liquid (olein) fractions.[22] Then melting and degumming removes impurities. Then the oil is filtered and bleached. Physical refining removes smells and coloration to produce "refined, bleached and deodorized palm oil" (RBDPO) and free sheer fatty acids, which are used in the manufacture of soaps, washing powder and other products. RBDPO is the basic palm oil product sold on the world's commodity markets. Many companies fractionate it further to produce palm olein for cooking oil, or process it into other products.[22]

Red palm oil

Since the mid-1990s, red palm oil has been cold-pressed and bottled for use as cooking oil, and blended into mayonnaise and salad oil.[23]

Butter and trans fat substitute

The highly saturated nature of palm oil renders it solid at room temperature in temperate regions, making it a cheap substitute for butter or trans fats in uses where solid fat is desirable, such as the making of pastry dough and baked goods. A recent rise in the use of palm oil in the food industry has partly come from changed labelling requirements that have caused a switch away from using trans fats.[24] Palm oil has been found to be a reasonable replacement for trans fats;[25] however, a small study conducted in 2009 found that palm oil may not be a good substitute for trans fats for individuals with already-elevated LDL levels.[26] The USDA agricultural research service states that palm oil is not a healthy substitute for trans fats.[27]

Biomass and bioenergy

Palm oil is used to produce both methyl ester and hydrodeoxygenated biodiesel.[28] Palm oil methyl ester is created through a process called transesterification. Palm oil biodiesel is often blended with other fuels to create palm oil biodiesel blends.[29] Palm oil biodiesel meets the European EN 14214 standard for biodiesels.[28] Hydrodeoxygenated biodiesel is produced by direct hydrogenolysis of the fat into alkanes and propane. The world's largest palm oil biodiesel plant is the Finnish-operated Neste Oil biodiesel plant in Singapore, which opened in 2011 and produces hydrodeoxygenated NEXBTL biodiesel.[30]

The organic waste matter that is produced when processing oil palm, including oil palm shells and oil palm fruit bunches, can also be used to produce energy. This waste material can be converted into pellets that can be used as a biofuel.[31] Additionally, palm oil that has been used to fry foods can be converted into methyl esters for biodiesel. The used cooking oil is chemically treated to create a biodiesel similar to petroleum diesel.[32]

In wound care

Although palm oil is applied to wounds for its supposed antimicrobial effects, research does not confirm its effectiveness.[33]

Production

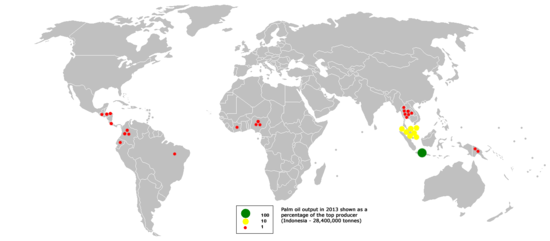

In 2012, the annual revenue received by Indonesia and Malaysia together, the top two producers of palm oil, was $40 billion.[34] Between 1962 and 1982 global exports of palm oil increased from around half a million to 2.4 million tonnes annually and in 2008 world production of palm oil and palm kernel oil amounted to 48 million tonnes. According to FAO forecasts by 2020 the global demand for palm oil will double, and triple by 2050.[35]

Indonesia

Indonesia is the world's largest producer of palm oil, surpassing Malaysia in 2006, producing more than 20.9 million tonnes.[34][36] Indonesia expects to double production by the end of 2030.[9] At the end of 2010, 60 percent of the output was exported in the form of crude palm oil.[37] FAO data show production increased by over 400% between 1994 and 2004, to over 8.66 million metric tonnes.

Malaysia

In 2012, Malaysia, the world's second largest producer of palm oil,[38] produced 18.79 million tonnes of crude palm oil on roughly 5,000,000 hectares (19,000 sq mi) of land.[39][40] Though Indonesia produces more palm oil, Malaysia is the world's largest exporter of palm oil having exported 18 million tonnes of palm oil products in 2011. China, Pakistan, the European Union, India and the United States are the primary importers of Malaysian palm oil products.[41]

Nigeria

As of 2011, Nigeria was the third-largest producer, with approximately 2.3 million hectares (5.7×106 acres) under cultivation. Until 1934, Nigeria had been the world's largest producer. Both small- and large-scale producers participated in the industry.[42][43]

Thailand

In 2013, Thailand produced 2.0 million tonnes of crude palm oil on roughly 626 thousand hectares. Thailand expects to produce 11 million tonnes of fresh palm nuts in 2016, down from more than 12 million in 2015, the shortfall due to Thailand's drought.[44]

Colombia

In the 1960s, about 18,000 hectares (69 sq mi) were planted with palm. Colombia has now become the largest palm oil producer in the Americas, and 35% of its product is exported as biofuel. In 2006, the Colombian plantation owners' association, Fedepalma, reported that oil palm cultivation was expanding to 1,000,000 hectares (3,900 sq mi). This expansion is being funded, in part, by the United States Agency for International Development to resettle disarmed paramilitary members on arable land, and by the Colombian government, which proposes to expand land use for exportable cash crops to 7,000,000 hectares (27,000 sq mi) by 2020, including oil palms. Fedepalma states that its members are following sustainable guidelines.[45]

Some Afro-Colombians claim that some of these new plantations have been expropriated from them after they had been driven away through poverty and civil war, while armed guards intimidate the remaining people to further depopulate the land, with coca production and trafficking following in their wake.[46]

Other countries

Benin

Palm is native to the wetlands of western Africa, and south Benin already hosts many palm plantations. Its 'Agricultural Revival Programme' has identified many thousands of hectares of land as suitable for new oil palm export plantations. In spite of the economic benefits, Non-governmental organisations (NGOs), such as Nature Tropicale, claim biofuels will compete with domestic food production in some existing prime agricultural sites. Other areas comprise peat land, whose drainage would have a deleterious environmental impact. They are also concerned genetically modified plants will be introduced into the region, jeopardizing the current premium paid for their non-GM crops.[47][48]

Cameroon

Cameroon had a production project underway initiated by Herakles Farms in the US.[49] However, the project was halted under the pressure of civil society organizations in Cameroon. Before the project was halted, Herakles left the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil early in negotiations.[50] The project has been controversial due to opposition from villagers and the location of the project in a sensitive region for biodiversity.

Kenya

Kenya's domestic production of edible oils covers about a third of its annual demand, estimated at around 380,000 metric tonnes. The rest is imported at a cost of around US$140 million a year, making edible oil the country's second most important import after petroleum. Since 1993 a new hybrid variety of cold-tolerant, high-yielding oil palm has been promoted by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations in western Kenya. As well as alleviating the country's deficit of edible oils while providing an important cash crop, it is claimed to have environmental benefits in the region, because it does not compete against food crops or native vegetation and it provides stabilisation for the soil.[51]

Ghana

Ghana has a lot of palm nut species, which may become an important contributor to the agriculture of the region. Although Ghana has multiple palm species, ranging from local palm nuts to other species locally called agric, it was only marketed locally and to neighboring countries. Production is now expanding as major investment funds are purchasing plantations, because Ghana is considered a major growth area for palm oil.

Markets

According to the Hamburg-based Oil World trade journal, in 2008 global production of oils and fats stood at 160 million tonnes. Palm oil and palm kernel oil were jointly the largest contributor, accounting for 48 million tonnes, or 30% of the total output. Soybean oil came in second with 37 million tonnes (23%). About 38% of the oils and fats produced in the world were shipped across oceans. Of the 60.3 million tonnes of oils and fats exported around the world, palm oil and palm kernel oil made up close to 60%; Malaysia, with 45% of the market share, dominated the palm oil trade.

Food label regulations

Previously, palm oil could be listed as "vegetable fat" or "vegetable oil" on food labels in the European Union (EU). From December 2014, food packaging in the EU is no longer allowed to use the generic terms "vegetable fat" or "vegetable oil" in the ingredients list. Food producers are required to list the specific type of vegetable fat used, including palm oil. Vegetable oils and fats can be grouped together in the ingredients list under the term "vegetable oils" or "vegetable fats" but this must be followed by the type of vegetable origin (e.g. palm, sunflower or rapeseed) and the phrase "in varying proportions".[52]

Supply chain institutions

The Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) was established in 2004[53] following concerns raised by non-governmental organizations about environmental impacts resulting from palm oil production. The organization has established international standards for sustainable palm oil production.[54] Products containing Certified Sustainable Palm Oil (CSPO) can carry the RSPO trademark.[55] Members of the RSPO include palm oil producers, environmental groups, and manufacturers who use palm oil in their products.[53][54]

The RSPO is applying different types of programmes to supply palm oil to producers.[56]

- Book and claim: no guarantee that the end product contains certified sustainable palm oil, supports RSPO-certified growers and farmers

- Identity preserved: the end user is able to trace the palm oil back to a specific single mill and its supply base (plantations)

- Segregated: this option guarantees that the end product contains certified palm oil

- Mass balance: the refinery is only allowed to sell the same amount of mass balance palm oil as the amount of certified sustainable palm oil purchased

GreenPalm is one of the retailers executing the book and claim supply chain and trading programme. It guarantees that the palm oil producer is certified by the RSPO. Through GreenPalm the producer can certify a specified amount with the GreenPalm logo. The buyer of the oil is allowed to use the RSPO and the GreenPalm label for sustainable palm oil on his products.[56]

Nutrition and health

Palm oil is an important source of calories and a food staple in poor communities.[57][58][59] However its overall health impacts, particularly in relation to cardiovascular disease, are controversial and subject to ongoing research.

Much of the palm oil that is consumed as food is cooking oil, to some degree oxidized rather than in the fresh state, and this oxidation appears to be responsible for the health risk associated with consuming palm oil.[60]

Cardiovascular disease

Several studies have linked palm oil to higher risks of cardiovascular disease including a 2005 study conducted in Costa Rica which indicated that replacing palm oil in cooking with polyunsaturated non-hydrogenated oils could reduce the risk of heart attacks,[61] and a 2011 analysis of 23 countries which showed that for each kilogram of palm oil added to the diet annually there was an increase in ischemic heart disease deaths (68 deaths per 100,000 increase) though the increase was much smaller in high-income countries.[62]

Palmitic acid

According to studies reported on by the Center for Science in the Public Interest (CSPI), excessive intake of palmitic acid, which makes up 44 percent of palm oil, increases blood cholesterol levels and may contribute to heart disease.[63] The CSPI also reported that the World Health Organization and the US National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute have encouraged consumers to limit the consumption of palmitic acid and foods high in saturated fat.[57][63] According to the World Health Organization, evidence is convincing that consumption of palmitic acid increases risk of developing cardiovascular diseases, placing it in the same evidence category as trans fatty acids.[64]

Comparison to trans fats

In response to negative reports on palm oil many food manufacturers transitioned to using hydrogenated vegetable oils in their products, which have also come under scrutiny for the impact these oils have on health.[65] A 2006 study supported by the National Institutes of Health and the USDA Agricultural Research Service concluded that palm oil is not a safe substitute for partially hydrogenated fats (trans fats) in the food industry, because palm oil results in adverse changes in the blood concentrations of LDL cholesterol and apolipoprotein B just as trans fat does.[26][66] However, according to two reports published in 2010 by the Journal of the American College of Nutrition palm oil is again an accepted replacement for hydrogenated vegetable oils[65] and a natural replacement for partially hydrogenated vegetable oils, which are a significant source of trans fats.[67]

Comparison with animal saturated fat

Not all saturated fats have equally cholesterolemic effects.[68] Studies have indicated that consumption of palm olein (which is more unsaturated) reduces blood cholesterol when compared to sources of saturated fats like coconut oil, dairy and animal fats.[68][69]

Acrolein

A 2009 study[70] tested the emission rates of acrolein, a toxic and malodorous breakdown product from glycerol, from the deep-frying of potatoes in red palm, olive, and polyunsaturated sunflower oils. The study found higher acrolein emission rates from the polyunsaturated sunflower oil (the scientists characterized red palm oil as "mono-unsaturated") and lower rates from both palm and olive oils. The World Health Organization established a tolerable oral acrolein intake of 7.5 mg/day per kilogram of body weight. Although acrolein occurs in French fries, the levels are only a few micrograms per kilogram. A 2011 study concluded a health risk from acrolein in food is unlikely.[71]

Social and environmental impacts

Social

The palm oil industry has had both positive and negative impacts on workers, indigenous peoples and residents of palm oil-producing communities. Palm oil production provides employment opportunities, and has been shown to improve infrastructure, social services and reduce poverty.[72][73][74] However, in some cases, oil palm plantations have developed lands without consultation or compensation of the indigenous people occupying the land, resulting in social conflict.[75][76][77] The use of illegal immigrants in Malaysia has also raised concerns about working conditions within the palm oil industry.[78][79][80]

Some social initiatives use palm oil cultivation as part of poverty alleviation strategies. Examples include the UN Food and Agriculture Organisation's hybrid oil palm project in Western Kenya, which improves incomes and diets of local populations,[81] and Malaysia's Federal Land Development Authority and Federal Land Consolidation and Rehabilitation Authority, which both support rural development.[82]

Food vs. fuel

The use of palm oil in the production of biodiesel has led to concerns that the need for fuel is being placed ahead of the need for food, leading to malnourishment in developing nations. This is known as the food versus fuel debate. According to a 2008 report published in the Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, palm oil was determined to be a sustainable source of both food and biofuel. The production of palm oil biodiesel does not pose a threat to edible palm oil supplies.[83] According to a 2009 study published in the Environmental Science and Policy journal, palm oil biodiesel might increase the demand for palm oil in the future, resulting in the expansion of palm oil production, and therefore an increased supply of food.[84]

Environmental

Palm oil cultivation has been criticized for impacts on the natural environment,[85][86] including deforestation, loss of natural habitats,[87] which has threatened critically endangered species such as the orangutan[88][89] and Sumatran tiger,[90] and increased greenhouse gas emissions.[86][91] Many palm oil plantations are built on top of existing peat bogs, and clearing the land for palm oil cultivation contributes to rising greenhouse gas emissions.[91][92]

Efforts to portray palm oil cultivation as sustainable have been made by organizations including the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil,[93] an industry group, and the Malaysian government, which has committed to preserve 50 percent of its total land area as forest.[10] According to research conducted by the Tropical Peat Research Laboratory, a group studying palm oil cultivation in support of the industry,[94] oil palm plantations act as carbon sinks, converting carbon dioxide into oxygen[95] and, according to Malaysia's Second National Communication to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, the plantations contribute to Malaysia's status as a net carbon sink.[96]

Environmental groups such as Greenpeace and Friends of the Earth oppose the use of palm oil biofuels, claiming that the deforestation caused by oil palm plantations is more damaging for the climate than the benefits gained by switching to biofuel and utilizing the palms as carbon sinks.[92][97][98]

Roundtable On Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO)

The Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) was created in 2004[53] following concerns raised by non-governmental organizations about environmental impacts related to palm oil production. The organization has established international standards for sustainable palm oil production.[54] Products containing Certified Sustainable Palm Oil (CSPO) can carry the RSPO trademark.[55] Members of the RSPO include palm oil producers, environmental groups and manufacturers who use palm oil in their products.[53][54]

Palm oil growers who produce Certified Sustainable Palm Oil have been critical of the organization because, though they have met RSPO standards and assumed the costs associated with certification, the market demand for certified palm oil remains low.[54][55] Low market demand has been attributed to the higher cost of Certified Sustainable Palm Oil, leading palm oil buyers to purchase cheaper non-certified palm oil. Palm oil is mostly fungible. In 2011, 12% of palm oil produced was certified "sustainable", though only half of that had the RSPO label.[99] Even with such a low proportion being certified, Greenpeace has argued that confectioners are avoiding responsibilities on sustainable palm oil, because it says that RSPO standards fall short of protecting rain forests and reducing greenhouse gases.[100]

See also

- Elaeis guineensis

- Food vs. fuel

- Palm sugar

- Tropical agriculture

- Social and environmental impact of palm oil

References

- ↑ Reeves, James B.; Weihrauch, John L.; Consumer and Food Economics Institute (1979). Composition of foods: fats and oils. Agriculture handbook 8-4. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Dept. of Agriculture, Science and Education Administration. p. 4. OCLC 5301713.

- ↑ Poku, Kwasi (2002). "Origin of oil palm". Small-Scale Palm Oil Processing in Africa. FAO Agricultural Services Bulletin 148. Food and Agriculture Organization. ISBN 92-5-104859-2.

- ↑ Behrman, E. J.; Gopalan, Venkat (2005). William M. Scovell, ed. "Cholesterol and Plants" (PDF). Journal of Chemical Education. 82 (12): 1791. doi:10.1021/ed082p1791.

- ↑ "Palm Oil Continues to Dominate Global Consumption in 2006/07" (PDF) (Press release). United States Department of Agriculture. June 2006. Retrieved 22 September 2009.

- ↑ Che Man, YB; Liu, J.L.; Jamilah, B.; Rahman, R. Abdul (1999). "Quality changes of RBD palm olein, soybean oil and their blends during deep-fat frying". Journal of Food Lipids. 6 (3): 181–193. doi:10.1111/j.1745-4522.1999.tb00142.x.

- ↑ Matthäus, Bertrand (2007). "Use of palm oil for frying in comparison with other high-stability oils". European Journal of Lipid Science and Technology. 109 (4): 400–409. doi:10.1002/ejlt.200600294.

- ↑ "Deforestation". www.sustainablepalmoil.org. Retrieved 2016-06-15.

- ↑ International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species; Pongo abelii. http://www.iucnredlist.org/details/39780/0 . Accessed: 2016-04-22

- 1 2 Natasha Gilbert (4 July 2012). "Palm-oil boom raises conservation concerns: Industry urged towards sustainable farming practices as rising demand drives deforestation". Nature.

- 1 2 Morales, Alex (18 November 2010). "Malaysia Has Little Room for Expanding Palm-Oil Production, Minister Says". Bloomberg. Retrieved 1 March 2013.

- ↑ Scott-Thomas, Caroline (17 September 2012). "French firms urged to back away from 'no palm oil' label claims". Foodnavigator. Retrieved 7 March 2013.

- ↑ Kiple, Kenneth F.; Conee Ornelas, Kriemhild, eds. (2000). The Cambridge World History of Food. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521402166. Retrieved 30 August 2012.

- ↑ Obahiagbon, F.I. (2012). "A Review: Aspects of the African Oil Palm (Elaeis guineesis Jacq.)" (PDF). American Journal of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 2 (3): 1–14. doi:10.3923/ajbmb.2012.106.119. Retrieved 30 August 2012.

- ↑ Diop, Anta (1989-07-01). The African Origin of Civilization: Myth or Reality?.

- ↑ "BRITISH COLONIAL POLICIES AND THE OIL PALM INDUSTRY IN THE NIGER DELTA REGION OF NIGERIA, 1900-1960." (PDF). African Study Monographs. 21 (1): 19–33. 2000.

- ↑ Bellis, Mary. "The History of Soaps and Detergents". About.com.

In 1864, Caleb Johnson founded a soap company called B.J. Johnson Soap Co., in Milwaukee. In 1898, this company introduced a soap made of palm and olive oils, called Palmolive.

- ↑ Ahsan H, Ahad A, Siddiqui WA (2015). "A review of characterization of tocotrienols from plant oils and foods". J Chem Biol. 8 (2): 45–59. doi:10.1007/s12154-014-0127-8. PMC 4392014

. PMID 25870713.

. PMID 25870713. - 1 2 Oi-Ming Lai, Chin-Ping Tan, Casimir C. Akoh (Editors) (2015). Palm Oil: Production, Processing, Characterization, and Uses. Elsevier. pp. 471, Chap. 16. ISBN 0128043466.

- ↑ "Oil, vegetable, palm per 100 g; Fats and fatty acids". Conde Nast for the USDA National Nutrient Database, Release SR-21. 2014. Retrieved 28 October 2016.

- ↑ Ng, M. H.; Choo, Y. M. (2016). "Improved Method for the Qualitative Analyses of Palm Oil Carotenes Using UPLC". Journal of Chromatographic Science. 54 (4): 633–8. doi:10.1093/chromsci/bmv241. PMC 4885407

. PMID 26941414.

. PMID 26941414. - ↑ "Palm oil products and the weekly shop". BBC Panorama. 22 February 2010. Retrieved 22 February 2010.

- 1 2 "Investment in Technology". PT. Asianagro Agungjaya.

- ↑ Nagendran, B.; Unnithan, U. R.; Choo, Y. M.; Sundram, Kalyana (2000). "Characteristics of red palm oil, a carotene- and vitamin E–rich refined oil for food uses" (PDF). Food and Nutrition Bulletin. 21 (2): 77–82.

- ↑ Lian Pin Koh and David S. Wilcove (2007). "Cashing in palm oil for conservation". Nature (subscription required). 448 (7157): 993–994. doi:10.1038/448993a.

- ↑ Heller, Lorraine (16 December 2005). "Palm oil 'reasonable' replacement for trans fats, say experts". Foodnavigator. Retrieved 1 March 2013.

- 1 2 "Palm Oil Not A Healthy Substitute For Trans Fats, Study Finds". Science Daily Website: Science News. ScienceDaily LLC. 2009-05-11. Retrieved 2010-05-12.

- ↑ Rosalie Marion Bliss (2009). "Palm Oil Not a Healthy Substitute for Trans Fats".

- 1 2 Rojas, Mauricio (3 August 2007). "Assessing the Engine Performance of Palm Oil Biodiesel". Biodiesel Magazine. Retrieved 25 February 2013.

- ↑ Amir Reza Sadrolhosseini; Muhammad Maarof Moskin; W. Mahmood. Mat. Yunus; Ahmad Mohammadi; Zainal Abidin Talib (24 August 2010). Optical Characterization of Palm Oil Biodiesel Blend (Report). Journal of Materials Science and Engineering. Retrieved 25 February 2013.

- ↑ Yahya, Yasmine (9 March 2011). "World's Largest Biodiesel Plant Opens in Singapore". The Jakarta Globe. Retrieved 25 February 2013.

- ↑ Choong, Meng Yew (27 March 2012). "Waste not the palm oil biomass". The Star Online. Retrieved 25 February 2013.

- ↑ Loh Soh Kheang; Choo Yuen May; Cheng Sit Food; Ma Ah Ngan (18 June 2006). Recovery and conversion of palm olein-derived used frying oil to methyl esters for biodiesel (PDF) (Report). Journal of Palm Oil Research. Retrieved 25 February 2013.

- ↑ Antimicrobial effects of palm kernel oil and palm oil Ekwenye, U.N and Ijeomah, King Mongkut's Institute of Technology Ladkrabang Science Journal, Vol. 5, No. 2, Jan-Jun 2005

- 1 2 Scientific American Board of Editors (December 2012), "The Other Oil Problem", Scientific American, 307 (6), p. 10, doi:10.1038/scientificamerican1212-10,

...such as Indonesia, the world's largest producer of palm oil.

- ↑ cite web |title = Palm oil - strategic source of renewable energy in Indonesia and Malaysia | last = Prokurat| first = Sergiusz ||url=http://wsge.edu.pl/files/JOMS/3-18-2013/Sergiusz_Prokurat_JoMS_3-18-2013_joms3.pdf

- ↑ Indonesia: Palm Oil Production Prospects Continue to Grow December 31, 2007, USDA-FAS, Office of Global Analysis

- ↑ "P&G may build oleochemical plant to secure future supply". The Jakarta Post. 2011-05-24. Retrieved 2012-06-15.

- ↑ Pakiam, Ranjeetha (3 January 2013). "Palm Oil Advances as Malaysia's Export Tax May Boost Shipments". Bloomberg. Retrieved 29 January 2013.

- ↑ "MPOB expects CPO production to increase to 19 million tonnes this year". The Star Online. 15 January 2013. Retrieved 29 January 2013.

- ↑ "MALAYSIA: Stagnating Palm Oil Yields Impede Growth". usda.gov. USDA Foreign Agricultural Service. 11 December 2012. Retrieved 29 January 2013.

- ↑ May, Choo Yuen (September 2012). "Malaysia: economic transformation advances oil palm industry". aocs.org. American Oil Chemists' Society. Retrieved 29 January 2013.

- ↑ Ayodele, Thompson (August 2010). "African Case Study: Palm Oil and Economic Development in Nigeria and Ghana; Recommendations for the World Bank's 2010 Palm Oil Strategy" (PDF). Initiative For Public Policy Analysis. Retrieved 8 December 2011.

- ↑ AYODELE, THOMPSON (October 15, 2010). "The World Bank's Palm Oil Mistake". The New York Times. Retrieved December 8, 2011.

- ↑ Arunmas, Phusadee (2016-05-30). "Drought crushes palm oil producers, leads to plea". Bangkok Post. Retrieved 30 May 2016.

- ↑ Fedepalma Annual Communication of Progress Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil, 2006

- ↑ Bacon, David. "Blood on the Palms: Afro-Colombians fight new plantations". See also "Unfulfilled Promises and Persistent Obstacles to the Realization of the Rights of Afro-Colombians," A Report on the Development of Ley 70 of 1993 by the Repoport Center for Human Rights and Justice, Univ. of Texas at Austin, Jul 2007.

- ↑ Pazos, Flavio (2007-08-03). "Benin: Large scale oil palm plantations for agrofuel". World Rainforest Movement.

- ↑ African Biodiversity Network (2007). Agrofuels in Africa: the impacts on land, food and forests : case studies from Benin, Tanzania, Uganda and Zambia. translated by. African Biodiversity Network.

- ↑ Report Assails Palm Oil Project in Cameroon September 5, 2012 New York Times

- ↑ "Cameroon changes mind on Herakles palm oil project". World Wildlife Fund. 21 June 2013. Retrieved 23 May 2016.

- ↑ "Hybrid oil palms bear fruit in western Kenya". UN FAO. 2003-11-24.

- ↑ New EU Food Labeling Rules Published (PDF) (Report). USDA Foreign Agricultural Service. 12 January 2012. Retrieved 29 January 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 Browne, Pete (6 November 2009). "Defining 'Sustainable' Palm Oil Production". The New York Times. Retrieved 16 February 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Gunasegaran, P. (8 October 2011). "The beginning of the end for RSPO?". The Star Online. Retrieved 16 February 2013.

- 1 2 3 Yulisman, Linda (4 June 2011). "RSPO trademark, not much gain for growers: Gapki". The Jakarta Post. Retrieved 16 February 2013.

- 1 2 "What is Green Palm?". Green Palm. Retrieved 4 October 2016.

- 1 2 Diet Nutrition and the Prevention of Chronic Diseases (Report). World Health Organization. 2003. p. 82,88. Retrieved 13 February 2013.

- ↑ "The other oil spill". The Economist. 24 June 2010. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

- ↑ Bradsher, Keith (19 January 2008). "A New, Global Oil Quandary: Costly Fuel Means Costly Calories". The New York Times. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

- ↑ Edem, D.O. (2002). "Palm oil: Biochemical, physiological, nutritional, hematological and toxicological aspects: A review". Plant Foods for Human Nutrition (Formerly Qualitas Plantarum). 57 (3): 319–341. doi:10.1023/A:1021828132707.

- ↑ Kabagambe; Baylin, A; Ascherio, A; Campos, H (November 2005). "The Type of Oil Used for Cooking Is Associated with the Risk of Nonfatal Acute Myocardial Infarction in Costa Rica". Journal of Nutrition (135 ed.). Journal of Nutrition. 135 (11): 2674–2679. PMID 16251629.

- ↑ Chen, B. K.; Seligman, B.; Farquhar, J. W.; Goldhaber-Fiebert, J. D. (2011). "Multi-Country analysis of palm oil consumption and cardiovascular disease mortality for countries at different stages of economic development: 1980-1997". Globalization and Health. 7 (1): 45. doi:10.1186/1744-8603-7-45. PMC 3271960

. PMID 22177258.

. PMID 22177258. - 1 2 Brown, Ellie; Jacobson, Michael F. (2005). Cruel Oil: How Palm Oil Harms Health, Rainforest & Wildlife (PDF). Washington, D.C.: Center for Science in the Public Interest. pp. iv,3–5. OCLC 224985333.

- ↑ Diet, Nutrition and the Prevention of Chronic Diseases, WHO Technical Report Series 916, Report of a Joint WHO/FAO Expert Consultation, World Health Organization, Geneva, 2003, p. 88 (Table 10)

- 1 2 Donald J McNamara (June 2010). "Palm Oil and Health: A Case of Manipulated Perception and Misuse of Science". J Am Coll Nutr. 29 (3 Suppl): 240S–244S. doi:10.1080/07315724.2010.10719840. PMID 20823485.

- ↑ Vega-López, Sonia; et al. (July 2006). "Palm and partially hydrogenated soybean oils adversely alter lipoprotein profiles compared with soybean and canola oils in moderately hyperlipidemic subjects". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. American Society for Nutrition. 84 (1): 54–62. PMID 16825681.

- ↑ K.C. Hayes; A. Pronczuk (29 June 2010). Replacing trans fat: the argument for palm oil with a cautionary note on interesterification (Report). Journal of the American College of Nutrition. PMID 20823487.

- 1 2 Ng, TK; Hassan, K; Lim, JB; Lye, MS; Ishak, R (1991). "Nonhypercholesterolemic effects of a palm-oil diet in Malaysian volunteers". American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 53 (4): 1015S–1020S. PMID 2012009.

- ↑ Chong, YH; Ng, TK (1991). "Effects of palm oil on cardiovascular risk" (PDF). Medical Journal of Malaysia. 46 (1): 41–50. PMID 1836037.

- ↑ Andreu-Sevilla, A.J.; Hartmann, A.; Burlo, F.; Poquet, N.; Carbonell-Barrachina, A.A. (2009). "Health Benefits of Using Red Palm Oil in Deep-frying Potatoes: Low Acrolein Emissions and High Intake of Carotenoids". Food Science and Technology International. 15: 15–22. doi:10.1177/1082013208100462.

- ↑ Abraham, Klaus; Andres, Susanne; Palavinskas, Richard; Berg, Katharina; Appel, Klaus E.; Lampen, Alfonso (2011). "Toxicology and risk assessment of acrolein in food". Molecular Nutrition & Food Research. 55 (9): 1277–1290. doi:10.1002/mnfr.201100481. Retrieved 2013-03-27.

- ↑ Budidarsono, Suseno; Dewi, Sonya; Sofiyuddin, Muhammad; Rahmanulloh, Arif. "Socio-Economic Impact Assessment of Palm Oil Production" (PDF). World Agroforestry Centre. Retrieved 30 January 2013.

- ↑ Norwana, Awang Ali Bema Dayang; Kunjappan, Rejani (2011). "The local impacts of oil palm expansion in Malaysia" (PDF). cifor.org. Center for International Forestry Research. Retrieved 30 January 2013.

- ↑ Ismail, Saidi Isham (9 November 2012). "Palm oil transforms economic landscape". Business Times. Retrieved 30 January 2013.

- ↑ "Palm oil cultivation for biofuel blocks return of displaced people in Colombia" (PDF) (Press release). Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre. 5 November 2007. Retrieved 30 January 2013.

- ↑ Colchester, Marcus; Jalong, Thomas; Meng Chuo, Wong (2 October 2012). "Free, Prior and Informed Consent in the Palm Oil Sector - Sarawak: IOI-Pelita and the community of Long Teran Kanan". Forest Peoples Program. Retrieved 30 January 2013.

- ↑ ""Losing Ground" - report on indigenous communities and oil palm development from LifeMosaic, Sawit Watch and Friends of the Earth". Forest Peoples Programme. 28 February 2008. Retrieved 30 January 2013.

- ↑ Indonesian migrant workers: with particular reference in the oil palm plantation industries in Sabah, Malaysia (Report). Biomass Society - Center for Southeast Asian Studies, Kyoto University. 11 December 2010.

- ↑ "Malaysia Plans High-Tech Card for Foreign Workers". ABC News. 9 January 2014.

- ↑ "Malaysia rounds up thousands of migrant workers". BBC News. 2 September 2013.

- ↑ hybrid oil palm project in Western Kenya FAO

- ↑ Ibrahim, Ahmad (31 December 2012). "Felcra a success story in rural transformation". New Straits Times. Retrieved 7 February 2013.

- ↑ Man Kee Kam; Kok Tat Tan; Keat Teong Lee; Abdul Rahman Mohamed (9 September 2008). Malaysian Palm oil: Surviving the food versus fuel dispute for a sustainable future (Report). Renewable and Sustainable Energy Review. Retrieved 26 February 2013.

- ↑ Corley, R. H. V. (2009). "How much palm oil do we need?". Environmental Science & Policy. 12 (2): 134–838. doi:10.1016/j.envsci.2008.10.011.

- ↑ Clay, Jason (2004). World Agriculture and the Environment. World Agriculture and the Environment. p. 219. ISBN 1-55963-370-0.

- 1 2 "Palm oil: Cooking the Climate". Greenpeace. 8 November 2007. Retrieved 30 January 2013.

- ↑ "The bird communities of oil palm and rubber plantations in Thailand" (PDF). The Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB). Retrieved 4 October 2016.

- ↑ "Palm oil threatening endangered species" (PDF). Center for Science in the Public Interest. May 2005.

- ↑ Shears, Richard (30 March 2012). "Hundreds of orangutans killed in north Indonesian forest fires deliberately started by palm oil firms". London: Associated Newspapers Ltd. Retrieved 1 April 2012.

- ↑ "Camera catches bulldozer destroying Sumatra tiger forest". World Wildlife Fund. 12 October 2010. Retrieved 30 January 2013.

- 1 2 Foster, Joanna M. (1 May 2012). "A Grim Portrait of Palm Oil Emissions". The New York Times. Retrieved 30 January 2013.

- 1 2 Rosenthal, Elisabeth (31 January 2007). "Once a Dream Fuel, Palm Oil May Be an Eco-Nightmare". The New York Times. Retrieved 30 January 2013.

- ↑ Adnan, Hanim (28 March 2011). "A shot in the arm for CSPO". The Star Online. Retrieved 16 October 2012.

- ↑ Masilamany, Joseph. "Peatlands are in danger of human encroachment and degradation worldwide.". Free Malaysia Today.

- ↑ "The truth about oil palms and carbon sinks". New Straits Times. 7 November 2010. Retrieved 30 January 2013.

- ↑ Malaysia: Second National Communication to the UNFCCC (PDF) (Report). Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment Malaysia. Retrieved 30 January 2013.

- ↑ Andre, Pachter (2007-10-12). "Greenpeace Opposing Neste Palm-Based Biodiesel". Epoch Times. Retrieved 2007-12-02.

- ↑ Fargione, Joseph; Hill, Jason; Tilman, David; Polasky, Stephen; Hawthorne, Peter (7 February 2008). "Land Clearing and the Biofuel Carbon Debt". Science. 319 (5867): 1235–1238. doi:10.1126/science.1152747. PMID 18258862.

- ↑ Watson, Elaine (5 October 2012). "WWF: Industry should buy into GreenPalm today, or it will struggle to source fully traceable sustainable palm oil tomorrow". Foodnavigator. Retrieved 22 February 2013.

- ↑ Growing pressure for stricter palm oil standards. Agritrade 19 Jan 2014

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Palm oil. |