Pale of Settlement

.jpg)

.svg.png)

The Pale of Settlement (Russian: Черта́ осе́длости, chertá osédlosti, Yiddish: דער תּחום-המושבֿ, der tkhum-ha-moyshəv, Hebrew: תְּחוּם הַמּוֹשָב, tcḥùm ha-mosháv) was a western region of Imperial Russia with varying borders that existed from 1791 to 1917, in which permanent residency by Jews was allowed and beyond which Jewish permanent residency was generally prohibited. However, Jews were excluded from residency in a number of cities within the Pale, and a limited number of categories of Jews—those ennobled, with university educations or at university, members of the most affluent of the merchant guilds and particular artisans, some military personnel and some services associated with them, as well as the families, and sometimes the servants of these—were allowed to live outside it. The archaic English term pale is derived from the Latin word palus, a stake, extended to mean the area enclosed by a fence or boundary.[1]

The Pale of Settlement included much of present-day Latvia and Lithuania (Baltic states); Belarus, Ukraine, Moldova, and Poland (East-Central Europe); and parts of western Russia. It extended from the eastern pale, or demarcation line, to the western Russian border with the Kingdom of Prussia (later the German Empire) and with Austria-Hungary. Furthermore, it comprised about 20% of the territory of European Russia and largely corresponded to historical borders of the former Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth and the Crimean Khanate.

The Russian Empire in the period of the existence of the Pale was predominantly Orthodox Christian. The area included in the Pale, with its large Jewish and Roman Catholic populations, was acquired through a series of military conquests and diplomatic maneuvers, between 1791 and 1835. While the religious nature of the edicts creating the Pale are clear (conversion to Russian Orthodoxy, the state religion, released individuals from the strictures), historians argue that the motivations for its creation and maintenance were primarily economic and nationalistic in nature.

The end of the enforcement and formal demarcation of the Pale coincided with the beginning of the First World War, and ultimately with the February and October Revolutions of 1917, i.e., the fall of the Russian Empire.

History

The Pale was first created by Catherine the Great in 1791, after several failed attempts by her predecessors, notably the Empress Elizabeth, to remove Jews from Russia entirely,[2] unless they converted to Russian Orthodoxy, the state religion. The reasons for its creation were primarily economic and nationalist.

The institution of the Pale became more significant following the Second Partition of Poland in 1793, since, until then, Russia's Jewish population had been rather limited; the dramatic westward expansion of the Russian Empire through the annexation of Polish-Lithuanian territory substantially increased the Jewish population. At its height, the Pale, including the new Polish and Lithuanian territories, had a Jewish population of over five million, and represented the largest component (40 percent) of the world Jewish population at that time.

From 1791 to 1835, and until 1917, there were differing reconfigurations of the boundaries of the Pale, such that certain areas were variously open or shut to Jewish residency, such as the Caucasus. At times, Jews were forbidden to live in agricultural communities, or certain cities, (as in Kiev, Sevastopol and Yalta), and forced to move to small provincial towns, thus fostering the rise of the shtetls. Jewish merchants of the First Guild (купцы первой гильдии, the wealthiest sosloviye of merchants in the Russian Empire), people with higher or special education, University students, artisans, army tailors, ennobled Jews, soldiers (drafted in accordance with the Recruit Charter of 1810), and their families had the right to live outside the Pale of Settlement.[3] In some periods, special dispensations were given for Jews to live in the major imperial cities, but these were tenuous, and several thousand Jews were expelled to the Pale from Saint Petersburg and Moscow as late as 1891.

During World War I, the Pale lost its rigid hold on the Jewish population when large numbers of Jews fled into the Russian interior to escape the invading German army. On March 20 (April 2 N.S.), 1917, the Pale was abolished by the Provisional Government decree, On abolition of confessional and national restrictions (Russian: Об отмене вероисповедных и национальных ограничений). A large portion of the Pale, together with its Jewish population, became part of Poland.

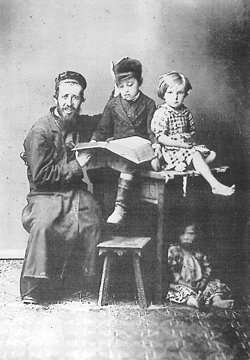

Jewish life in the Pale

Jewish life in the shtetls (Yiddish: שטעטלעך shtetlekh "little towns") of the Pale of Settlement was hard and poverty-stricken.[4] Following the Jewish religious tradition of tzedakah (charity), a sophisticated system of volunteer Jewish social welfare organizations developed to meet the needs of the population. Various organizations supplied clothes to poor students, provided kosher food to Jewish soldiers conscripted into the Tsar's army, dispensed free medical treatment for the poor, offered dowries and household gifts to destitute brides, and arranged for technical education for orphans. According to historian Martin Gilbert's Atlas of Jewish History, no province in the Pale had less than 14% of Jews on relief; Lithuanian and Ukrainian Jews supported as much as 22% of their poor populations.[5]

The concentration of Jews in the Pale made them easy targets for pogroms and anti-Jewish riots by the majority population; these, along with the repressive May Laws, often devastated whole communities. Though attacks occurred throughout the existence of the Pale, particularly devastating anti-Jewish pogroms occurred from 1881–83 and from 1903–1906,[6] targeting hundreds of communities, assaulting thousands of Jews, and causing considerable property damage.

One outgrowth of the concentration of Jews in a circumscribed area was the development of the modern yeshiva system. Until the beginning of the 19th century, each town supported its own advanced students who learned in the local synagogue with the rabbinical head of the community. Each student would eat his meals in a different home each day, a system known as essen teg ("eating days").

After 1886, the Jewish quota was applied to education, with the percentage of Jewish students limited to no more than 10% within the Pale, 5% outside the Pale and 3% in the capitals of Moscow, St. Petersburg, and Kiev. The quotas in the capitals, however, were increased slightly in 1908 and 1915.

Amidst the difficult conditions in which the Jewish population lived and worked, the courts of Hasidic dynasties flourished in the Pale. Thousands of followers of rebbes such as the Gerrer Rebbe Yehudah Aryeh Leib Alter (known as the Sfas Emes), the Chernobyler Rebbe, and the Vizhnitzer Rebbe flocked to their towns for the Jewish holidays and followed their rebbes' minhagim (Jewish practices) in their own homes.

The tribulations of Jewish life in the Pale of Settlement were immortalized in the writings of Yiddish authors such as humorist Sholom Aleichem, whose novel Tevye der Milchiger (Tevye the Milkman) (in the form of the narration of Tevye from a fictional shtetl of Anatevka to the author) form the basis of the theatrical (and subsequent film) production Fiddler on the Roof. Because of the harsh conditions of day-to-day life in the Pale, some two million Jews emigrated from there between 1881 and 1914, mainly to the United States. However, this exodus did not affect the stability of the Jewish population of the Pale, which remained at 5 million people due to its high birthrate.

Territories of the Pale

The Pale of Settlement included the following areas.

1791

The ukase of Catherine the Great of December 23, 1791 limited the Pale to:

- Western Krai:

- Mogilev Governorate

- Polotsk Governorate (later reorganized into Vitebsk Governorate)

- Little Russia (Ukraine):

- Kiev Governorate

- Chernigov Governorate

- Novgorod-Seversky Viceroyalty (later became Poltava Governorate)

- Novorossiya Governorate

1794

After the Second Partition of Poland, the ukase of June 23, 1794, the following areas were added:

- Minsk Governorate

- Mogilev Governorate

- Polotsk Governorate

- Kiev Governorate

- Volhynian Governorate

- Podolia Governorate

1795

After the Third Partition of Poland, the following areas were added:

1805–1835

After 1805 the Pale gradually shrank, and became limited to the following areas:

- Lithuanian governorates

- Southwestern Krai

- Belarus without rural areas

- Malorossiya (Little Russia or Ukraine) without rural areas

- Chernigov Governorate

- Novorossiya without Nikolaev and Sevastopol

- Kiev Governorate without Kiev

- Baltic governorates closed for arriving Jews

Congress Poland did not belong to the Pale of Settlement[3]

Rural areas for 50 versts (53 km) from the western border were closed for new settlement of the Jews.

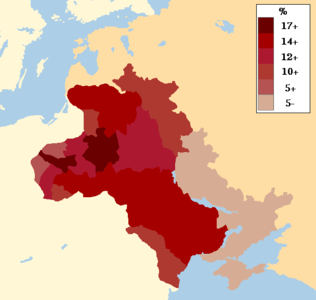

Final demographics

According to the 1897 census, the guberniyas had the following percentages of Jews:[7]

- Northwestern Krai (whole; Lithuania, Belarus):

- Vilna Governorate [12.86%]

- Kovno Governorate [13.77%]

- Grodno Governorate [17.49%]

- Minsk Governorate [16.06%]

- Mogilev Governorate [12.09%]

- Vitebsk Governorate (some parts of it are in Pskov and Smolensk Oblasts now) [11.79%]

- Southwestern Krai (part; now in Ukraine):

- Kiev Governorate [12.19%]

- Volhynian Governorate [13.24%]

- Podolia Governorate [12.28%]

- Polish governorates (lands of Congress Poland):

- Warsaw guberniya (Варшавская губерния (Мазовецкая губерния 1837–44)) [18.22%]

- Lublin guberniya (Люблинская губерния) [13.46%]

- Płock guberniya (Плоцкая губерния) [9.29%]

- Kalisz guberniya (Калишская губерния) [8.52%]

- Piotrkow guberniya (Пётроковская губерния) [15.85%]

- Kielce guberniya (Келецкая губерния (Краковская губерния 1837–44)) [10.92%]

- Radom guberniya (Радомская губерния) [13.78%]

- Siedlce guberniya (Седлецкая губерния (Подлясская губерния 1837–44)) [15.69%]

- Augustów guberniya (Августовская губерния, 1837–67), split into:

Others:

- Chernigov Governorate (some parts of it are in Bryansk Oblast now) [4.98%]

- Poltava Governorate [3.99%]

- Taurida Governorate (Crimea) [Jewish 4.20% + Karaite 0.43%]

- Kherson Governorate [12.43%]

- Bessarabia Governorate [11.81%]

- Yekaterinoslav Governorate [4.78%]

In 1882 it was forbidden for Jews to settle in rural areas.

The following cities within the Pale were excluded from it:

- Kiev (the ukase of December 2, 1827: eviction of Jews from Kiev)

- Nikolaev

- Sevastopol

- Yalta

See also

- English Pale around Dublin, Ireland

- Pale of Calais, English territory in France from 1360 to 1558

- May Laws

- Pogrom

- Hippolytus Lutostansky

- History of the Jews in Russia

- History of the Jews in Poland

- History of the Jews in the Soviet Union

- Antisemitism in the Russian Empire

- Antisemitism in the Soviet Union

- Antisemitism in the Russian Federation

References

- ↑ "pale, n.1." OED Online. Oxford University Press, September 2016. Retrieved October 24, 2016.

- ↑ Producer, director, production company unknown (October 24, 2011). История России, 7. Русские цари Елизавета Петровна [The History of Russia, 7: Russian Tsars, Yelizaveta Petrovna] (streaming video) (in Russian). Event occurs at 10:30. Retrieved September 29, 2016 – via YouTube.

[Ed. note: Attitudes toward the Jews are to be found at this time point. Production may be one of Moscow University and the Academy of Arts (Московский университет и Академия художеств).]

- 1 2 Jankowski, Tomasz [attr.] (May 3, 2014). "Who could live outside the Pale of Settlement?" (blogpost). JewishFamilySearch.com. Retrieved September 29, 2016.

[Presents 14 groups of Jews to whom permission might be granted to live outside of the Pale, indicating additional conditions, and presenting three reasons for temporary permissions to leave, for the 13 governates of the Russian Empire; the bogpost is by an academic historian, and states: 'These rules was regulated by the Law on Social Estates and the Law on Passports printed in vol. 9 and 14 of Свод законов Российской империи.']

- ↑ "Shtetl". Encyclopaedia Judaica. Jewish Virtual Library, The Gale Group.

- ↑ Rabbi Ken Spiro. "History Crash Course #56: Pale of Settlement". aish.com. Retrieved 19 August 2015.

- ↑ "Modern Jewish History: Pogroms". Encyclopaedia Judaica. Jewish Virtual Library, The Gale Group. 2008. Retrieved 19 August 2015.

- ↑ Первая всеобщая перепись населения Российской Империи 1897 г.: Распределение населения по вероисповеданиям и регионам [The first general census of the population of the Russian Empire in 1897: Population by religions and regions]. Демоскоп Weekly (in Russian). Retrieved 30 September 2013.

- Abramson, Henry, "Jewish Representation in the Independent Ukrainian Governments of 1917–1920", Slavic Review, Vol. 50, No. 3 (Autumn 1991), pp. 542–550.

External links

- The Pale of Settlement (with a map) at Jewish Virtual Library

- The Pale of Settlement (with map and additional documents) at The YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe

- Jewish Communities in the Pale of Settlement (with a map)

- friends-partners.org (with map)

- Life in the Pale of Settlement (with photos)

- Jewish Encyclopedia - Jewish Encyclopedia

- aish.com

- britannica.com

- digital.library.mcgill.ca (with map)

- Map of area in the Polish era (Royal Museums, Greenwich)

- The decree "On abolition of confessional and national restrictions", passed by the Provisional Government on March 20, 1917 (in Russian)