Osorkon IV

| Osorkon IV | |

|---|---|

| Shilkanni, So | |

|

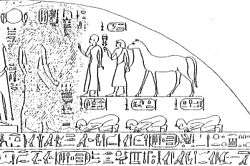

Relief thought to depict Osorkon IV, from Tanis[1] | |

| Pharaoh | |

| Reign | 730 – 715/13 BC (22nd or 23rd Dynasty) |

| Predecessor | Shoshenq V or Pedubast II |

| Successor |

as pharaoh: Shabaka (25th Dynasty) as king of Tanis: Gemenefkhonsbak (not directly) |

|

| |

| Mother | Tadibast III |

| Died | before 712 BC |

Usermaatre Osorkon IV was an ancient Egyptian pharaoh during the late Third Intermediate Period. Traditionally considered the very last king of the 22nd Dynasty, he was de facto little more than ruler in Tanis and Bubastis, in Lower Egypt. He is generally – though not universally – identified with the King Shilkanni mentioned by Assyrian sources, and with the biblical So, King of Egypt from the Books of Kings.

Osorkon ruled during one of the most chaotic and politically fragmented periods of ancient Egypt, in which the Nile Delta was dotted with small Libyan kingdoms and principalities and Meshwesh dominions; as the last heir of the Tanite rulers, he inherited the easternmost parts of these kingdoms, the most involved in all the political and military upheavals that soon would afflict the Near East. During his reign, he had to face the power, and ultimately submit himself—to the Kushite King Piye during Piye's conquest of Egypt. Osorkon IV also had to deal with the threatening Neo-Assyrian Empire outside his eastern borders.

Reign

Early years

Osorkon IV ascended to the throne of Tanis in c. 730 BC,[3] at the end of the long reign of his predecessor Shoshenq V of the 22nd Dynasty,[4][5][6][7] who was possibly also his father.[8] However, this somewhat traditional collocation was first challenged in 1970 by Karl-Heinz Priese who preferred to place Osorkon IV in a lower–Egyptian branch of the 23rd Dynasty, right after the reign of the shadowy pharaoh Pedubast II;[9] this placement found the support of a certain number of scholars.[10][11][12][13] Osorkon's mother, named on a electrum aegis of Sekhmet now in the Louvre, was Tadibast III.[4] Osorkon IV's realm was restricted only to the district of Tanis (Rˁ-nfr) and the territory of Bubastis, both in the eastern Nile Delta.[14] His neighbors were Libyan princes and Meshwesh chiefs who ruled their small realms outside of his authority.[8]

Around 729/28 BC, soon after his accession, Osorkon IV faced the crusade led by the Kushite pharaoh Piye of the Nubian 25th Dynasty. Along with other rulers of Lower and Middle Egypt – mainly Nimlot of Hermopolis, Iuput II of Leontopolis and Peftjauawybast of Herakleopolis – Osorkon IV joined the coalition led by the Chief of the West Tefnakht in order to oppose the Nubian.[15] However, Piye's advance was unstoppable and the opposing rulers surrendered one after another: Osorkon IV found it wise to reach the Temple of Ra at Heliopolis and pay homage to his new overlord Piye personally—[16] an action which was soon imitated by the other rulers. As reported on his Victory Stela, Piye accepted their submission, but Osorkon and most of the rulers were not allowed to enter the royal enclosure because they were not circumcised and had eaten fish, both abominations in the eyes of the Nubian.[17][18] Nevertheless, Osorkon IV and the others were allowed to keep their former domains and authority.[19][20]

The Assyrian threat

In 726/25 BC Hoshea, the last King of Israel, rebelled against the Assyrian King Shalmaneser V who demanded an annual tribute, and sought the support of So, King of Egypt (2 Kings 17:4) who, as already mentioned, was most likely Osorkon IV (see below). For reasons which remained unknown – possibly in order to remain neutral towards the powerful Neo-Assyrian Empire, or simply because he didn't have enough power or resources – King So didn't help Hoshea, who was subsequently defeated and deposed by Shalmaneser V. The Kingdom of Israel ceased to exist, and many Israelites were brought to Assyria as exiles.[21][22]

.jpg)

In 720 BC, a revolt occurred in Palestine against the new Assyrian King Sargon II, led by King Hanno (also Hanun and Hanuna) of Gaza who sought the help of "Pirʾu of Musri", a term most probably meaning "Pharaoh of Egypt" and referring to Osorkon IV. Assyrian sources claim that this time the Egyptian king did send a turtanu (an army–commander) called Reʾe or Reʾu (his Egyptian name was Raia, though in the past it was read Sibʾe) as well as troops in order to support his neighboring ally. However, the coalition was defeated in battle at Raphia. Reʾe fled back to Egypt, Raphia and Gaza were looted and Hanno was burnt alive by the Assyrians.[21][22] A different opinion came from Israeli scholar Dan'el Kahn who proposed an earlier datation for the accession of Piye's successor Shabaka: in his point of view, Shabaka was already ruling over the whole of Egypt before 720 BC, and Reʾe was in fact a Nubian turtanu serving him rather than an Egyptian one serving Osorkon IV.[23]

In 716 BC, Sargon II almost reached Egypt's boundaries. Feeling directly threatened this time, Osorkon IV (here called Shilkanni by Assyrian sources, see below) was carefully diplomatic: he personally met the Assyrian king at the "Brook of Egypt" (most likely el-Arish) and tributed him with a present which Sargon personally described as "twelve large horses of Egypt without equals in Assyria". The Assyrian king appreciated his gifts and did not take action against Osorkon IV.[24]

End

Shortly after, Osorkon IV and his dynasty vanished into obscurity. His death should have occurred between 715 and 713 BC, after 16/18 years of reign,[25] as he was apparently gone when King Iamani of Ashdod sought refuge from Sargon II in Egypt around 712 BC or possibly later, only to be caught by a pharaoh of the 25th Dynasty who returned him to the Assyrians in chains.[26] Kahn believed that this pharaoh was Shabaka, who might have previously deposed Osorkon IV, "guilty" for being too philo-Assyrian.[27] A few decades later a man called Gemenefkhonsbak, possibly a descendant of the now-defunct dynasty, claimed for himself the pharaonic royal titles and ruled in Tanis as its prince.[28]

Identification with Shilkanni and So

It is believed that Shilkanni is a rendering of (U)shilkan, which in turn is derived from (O)sorkon – hence Osorkon IV – as first proposed by William F. Albright in 1956.[29][30] This identification is accepted by several scholars[2][21][31][6][32][33][34] while others remain uncertain[35] or even skeptical.[36] Shilkanni is reported by Assyrians as "King of Musri": this location, once believed to be a country in northern Arabia by the orientalist Hans Alexander Winckler, is certainly to be identified with Egypt instead.[30] In the same way, the "Pir'u of Musri" to whom Hanno of Gaza asked for help in 720 BC could only have been Osorkon IV.[37] The identity of the biblical King So is somewhat less definite. Generally, an abbreviation of (O)so(rkon) is again considered the most likely by several scholars,[31][6][32][38][39][40][41] but the concurrent hypothesis which equates So with the city of Sais, hence with King Tefnakht, is supported by a certain number of scholars.[42][43][44][45]

Attestations

Osorkon IV is attested by Assyrian documents (as Shilkanni and other epithets) and probably also by the Books of Kings (as King So), while Manetho's epitomes seem to have ignored him.[46] He is undoubtedly attested by the well-known Victory Stela of Piye[47] on which he is depicted while prostrating in front of the owner of the stela along with other submitted rulers. Another finding almost certainly referring to him is the aforementioned aegis of Sekhmet, found at Bubastis and mentioning a King Osorkon son of queen Tadibast who–as the name does not coincide with those of any of the other Osorkon kings' mothers–can only be Osorkon IV's mother.[4]

About the throne name

Osorkon's throne name was thought to be Aakheperre Setepenamun from a few monuments naming a namesake pharaoh Osorkon, such as a faience seal and a relief–block, both in the Rijksmuseum van Oudheden in Leiden,[6] but this attribution was questioned by Frederic Payraudeau in 2000. According to him, these findings could rather be assigned to an earlier Aakheperre Osorkon – i.e., the distant predecessor Osorkon the Elder of the 21st Dynasty – thus implying that Osorkon IV's real throne name was unknown.[48] Furthermore, in 2010/11 a French expedition discovered in the Temple of Mut at Tanis two blocks bearing a relief of a King Usermaa(t)re Osorkonu, depicted in a quite archaizing style, which at first were attributed to Osorkon III.[1] In 2014, on the basis of the style of both the relief and the royal name, Aidan Dodson rejected the identification of this king with both the already-known kings Usermaatre Osorkon (Osorkon II and III) and stated that he was rather Osorkon IV with his true throne name.[2] A long-known, archaizing "glassy faience" statuette fragment from Memphis now exhibited at the Petrie Museum (UC13128) which is inscribed for one King Usermaatre, had been tentatively attributed to several pharaohs from Piye to Rudamun of the Theban 23rd Dynasty and even to Amyrtaios of the 28th Dynasty, but may in fact represent Osorkon IV.[49]

See also

- Pharaohs in the Bible for other historical or conjectural pharaohs cited in the Bible

References

- 1 2 3 Dodson 2014, pp. 7–8

- 1 2 3 4 Dodson 2014, pp. 9–10

- ↑ Kitchen 1996, § 92

- 1 2 3 Berlandini 1979, pp. 100–101

- ↑ Edwards 1982, p. 569

- 1 2 3 4 Schneider 1985, pp. 261–263

- ↑ Mitchell 1991, p. 340

- 1 2 Grimal 1992, pp. 330–31

- ↑ Priese 1970, p. 20 n. 23

- ↑ Leahy 1990, p. 89

- ↑ von Beckerath 1997, p. 99

- ↑ see also Jansen-Winkeln 2006, pp. 246–47 and references therein.

- ↑ Wilkinson (2011, p. XVIII) recognizes Osorkon IV as the last ruler of the 22nd Dynasty, though placing Pedubast II before him.

- ↑ Kitchen 1996, § 82; 92

- ↑ Kitchen 1996, § 325

- ↑ Grimal 1992, p. 398

- ↑ Kitchen 1996, §§ 325–26

- ↑ Wilkinson 2011, p. 397

- ↑ Grimal 1992, p. 339

- ↑ Wilkinson 2011, p. 398

- 1 2 3 Grimal 1992, pp. 341–42

- 1 2 Kitchen 1996, §§ 333ff

- ↑ Kahn 2001, pp. 11–12

- ↑ Kitchen 1996, § 336

- ↑ Kitchen 1996, § 526; revised table 6

- ↑ Kitchen 1996, §§ 463–64

- ↑ Kahn 2001, pp. 9–10

- ↑ Kitchen 1996, § 357

- ↑ Albright 1956, p. 24

- 1 2 Kitchen 1996, § 115

- 1 2 Edwards 1982, p. 576

- 1 2 Mitchell 1991, p. 345

- ↑ Kitchen 1996, § 115; 463

- ↑ Wilkinson 2011, pp. 399–400

- ↑ Jansen-Winkeln 2006, p. 260 & n. 177

- ↑ Yoyotte 1971, pp. 43–44

- ↑ Kitchen 1996, §§ 335; 463

- ↑ Kitchen 1996, §§ 333ff; 463–64

- ↑ Patterson 2003, pp. 196–97

- ↑ Clayton 2006, pp. 182–83

- ↑ Dodson 2014, p. 9

- ↑ Goedicke 1963, pp. 64–66

- ↑ Redford 1985, p. 197 & n. 56

- ↑ see also Kitchen 1996, § 463 and references therein.

- ↑ Kahn 2001, pp. 13–14

- ↑ Kitchen 1996, § 418

- ↑ Jansen-Winkeln 2006, p. 246, n. 91

- ↑ Payraudeau 2000, pp. 78ff

- ↑ Brandl 2011, pp. 17–18

Bibliography

- Albright, William F. (1956). "Further Synchronisms between Egypt and Asia in the Period 935-685 BC". BASOR. 141: 23–27.

- von Beckerath, Jürgen (1994). "Osorkon IV = Herakles". Göttinger Miszellen. 139: 7–8.

- von Beckerath, Jürgen (1997). Chronologie des pharaonischen Ägyptens. Mainz am Rhein: Münchner Ägyptologische Studien 46.

- Berlandini, Jocelyne (1979). "Petits monuments royaux de la XXIe à la XXVe dynastie". Hommages à la mémoire de Serge Sauneron, vol. I, Egypte pharaonique. Cairo, Imprimerie de l'Institut d'Archeologie Orientale. pp. 89–114.

- Brandl, Helmut (2011). "Eine archaisierende Königsfigur der späten Libyerzeit (Osorkon IV ?)". In Bechtold, E.; Gulyás, A.; Hasznos, A. From Illahun to Djeme. Papers Presented in Honour of Ulrich Luft. Archaeopress. pp. 11–23. ISBN 978 1 4073 0894 4.

- Clayton, Peter A. (2006). Chronicle of the Pharaohs: The Reign-by-Reign Record of the Rulers and Dynasties of Ancient Egypt. London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-28628-0.

- Dodson, Aidan (2014). "The Coming of the Kushites and the Identity of Osorkon IV". In Pischikova, Elena. Thebes in the First Millennium BC PDF. Cambridge Scholars publishing. pp. 6–12. ISBN 978-1-4438-5404-7.

- Dodson, Aidan; Hilton, Dyan (2004). The Complete Royal Families of Ancient Egypt. London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-05128-3.

- Edwards, I.E.S. (1982). "Egypt: from the Twenty-second to the Twenty-fourth Dynasty". In Edwards, I.E.S. The Cambridge Ancient History (2nd ed.), vol. III, part 1. Cambridge University Press. pp. 534–581. ISBN 0 521 22496 9.

- Goedicke, Hans (1963). "The end of "So, King of Egypt"". BASOR. 171: 64–66.

- Grimal, Nicolas (1992). A History of Ancient Egypt. Oxford: Blackwell Books. p. 512. ISBN 9780631174721.

- Jansen-Winkeln, Karl (2006). "Third Intermediate Period". In Hornung, Erik; Krauss, Rolf; Warburton, David A. Ancient Egyptian Chronology. Brill, Leiden/Boston. pp. 234–264. ISBN 978 90 04 11385 5.

- Kahn, Dan'el (2001). "The Inscription of Sargon II at Tang-I Var and the Chronology of Dynasty 25". Orientalia. 70: 1–18.

- Kitchen, Kenneth A. (1996). The Third Intermediate Period in Egypt (1100–650 BC). Warminster: Aris & Phillips Limited. p. 608. ISBN 0-85668-298-5.

- Leahy, Anthony, ed. (1990). Libya and Egypt c. 1300–750 BC. University of London. Centre of Near and Middle Eastern Studies. p. 200. ISBN 0 521 22717 8.

- Mitchell, T. C. (1991). "Israel and Judah c. 750–700 B.C.". In Edwards, I.E.S. The Cambridge Ancient History (2nd ed.), vol. III, part 2. Cambridge University Press. pp. 322–370. ISBN 0 521 22717 8.

- Patterson, Richard D. (2003). "The Divided Monarchy: Sources, Approaches, and Historicity". In Grisanti, Michel A.; Howard, David M. Giving the sense: understanding and using Old Testament historical texts. Kregel. pp. 179–200. ISBN 978-0-8254-2892-0.

- Payraudeau, Frederic (2000). "Remarques sur l'identité du premier et du dernier Osorkon". Göttinger Miszellen. 178: 75–80.

- Porter, Robert M. (2011). "Osorkon III of Tanis: the Contemporary of Piye?". Göttinger Miszellen. 230: 111–112.

- Priese, Karl-Heinz (1970). "Der Beginn der Kuschitischen Herrschaft in Ägypten". ZÄS. 98: 16–32.

- Redford, Donald B. (1985). "The Relations between Egypt and Israel from El-Amarna to the babylonian Conquest". Proceedings of the International Congress on Biblical Archaeology, Jerusalem, April 1984. Biblical Archaeology Today. pp. 192–203.

- Schneider, Hans D. (1985). "A royal epigone of the 22nd Dynasty. Two documents of Osorkon IV in Leiden". Mélanges Gamal Eddin Mokhtar, vol. II. Institut français d'archéologie orientale du Caire. pp. 261–267.

- Wilkinson, Toby (2011). The Rise and Fall of Ancient Egypt. New York: Random House. p. 560. ISBN 9780747599494.

- Yoyotte, Jean (1971). "Notes et documents pour servir à l'historie de Tanis". Kêmi. XXI: 36–45.

External links

Media related to Osorkon IV at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Osorkon IV at Wikimedia Commons