Ornithomimus

| Ornithomimus Temporal range: Late Cretaceous, 76.5–66.5 Ma | |

|---|---|

| | |

| Mounted O. edmontonicus skeleton, Royal Ontario Museum | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Order: | Saurischia |

| Suborder: | Theropoda |

| Clade: | †Ornithomimosauria |

| Family: | †Ornithomimidae |

| Genus: | †Ornithomimus Marsh, 1890 |

| Type species | |

| †Ornithomimus velox Marsh, 1890 | |

| Other species | |

|

†O. edmontonicus | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Dromiceiomimus? Russell, 1972 | |

Ornithomimus (/ˌɔːrnᵻθəˈmaɪməs, -θoʊ-/;[2] "bird mimic") is a genus of ornithomimid dinosaurs from the Late Cretaceous Period of what is now North America. Ornithomimus was a swift bipedal theropod which fossil evidence indicates was covered in feathers, equipped with a small toothless beak that may indicate an omnivorous diet. It is usually classified into two species: the type species, Ornithomimus velox, and a referred species, Ornithomimus edmontonicus. O. velox was named in 1890 by Othniel Charles Marsh on the basis of a foot and partial hand from the late Maastrichtian-age Denver Formation of Colorado, United States. Another seventeen species have been named since, though most of them have subsequently been assigned to new genera or shown to be not directly related to Ornithomimus velox. The best material of species still considered part of the genus has been found in Alberta, Canada, representing the species O. edmontonicus, known from several skeletons from the early Maastrichtian Horseshoe Canyon Formation. Additional species and specimens from other formations are sometimes classified as Ornithomimus, such as Ornithomimus samueli (alternately classified in the genera Dromiceiomimus or Struthiomimus) from the earlier, Campanian-age Dinosaur Park Formation of Alberta.

Description

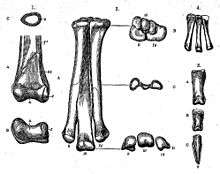

Like other ornithomimids, species of Ornithomimus are characterized by feet with three weight-bearing toes, long slender arms, and long necks with birdlike, elongated, toothless, beaked skulls. They were bipedal and superficially resembled ostriches. They would have been swift runners. They had very long limbs, hollow bones, and large brains and eyes. The brains of ornithomimids in general were large for non-avialan dinosaurs, but this may not necessarily be a sign of greater intelligence; some paleontologists think that the enlarged portions of the brain were dedicated to kinesthetic coordination.[3] The bones of the hands are remarkably sloth-like in appearance, which led Henry Fairfield Osborn to suggest that they were used to hook branches during feeding.

Ornithomimus differ from other ornithomimids, such as Struthiomimus, in having shorter torsos, long slender forearms, very slender, straight hand and foot claws and in having hand bones (metacarpals) and fingers of similar lengths.[4]

The two Ornithomimus species today seen as possibly valid differ in size. In 2010 Gregory S. Paul estimated the length of O. edmontonicus at 3.8 m (12 ft), its weight at 170 kilograms (370 lb). One of its specimens, CMN 12228, preserves a femur (thigh bone) 46.8 centimetres (18.4 in) long. O. velox, the type species of Ornithomimus, is based on material of a smaller animal. Whereas the holotype of O. edmontonicus, CMN 8632, preserves a second metacarpal eighty-four millimetres long, the same element with O. velox measures only fifty-three millimetres.

Feathers and skin

Ornithomimus, like many dinosaurs, was long thought to have been scaly. However, beginning in 1995, several specimens of Ornithomimus have been found preserving evidence of feathers.

In 1995, 2008 and 2009, three Ornithomimus edmontonicus specimens with evidence of feathers were found; two adults with carbonized traces on the lower arm, indicating the former presence of pennaceous feather shafts, and a juvenile with impressions of feathers, of which were up to five centimetres in length, in the form of hair-like filaments covering the rump, legs and neck was also discovered. The fact that the feather imprints were found in sandstone, previously thought to not be able to support such impressions, raised the possibility of finding similar structures with more careful preparation of future specimens. A study describing the fossils in 2012 concluded that O. edmontonicus was covered in plumaceous feathers at all growth stages, and that only adults had pennaceous wing-like structures, suggesting that wings may have evolved for mating displays.[5] In 2014, Christian Foth and others argued that the evidence was insufficient to conclude that the forelimb feathers of Ornithomimus were necessarily pennaceous, citing the fact that the monofilamentous wing feathers in cassowaries would likely leave similar traces.[6]

A fourth feathered specimen of Ornithomimus, this time from the lower portion of the Dinosaur Park Formation, was described in October, 2015 by Aaron van der Reest, Alex Wolfe, and Phil Currie. It was the first Ornithomimus specimen to preserve the feathers along the tail. The feathers, though crushed and distorted, bore numerous similarities with those of the modern ostrich, both in their structure and distribution on the body. Skin impressions were also preserved in the 2015 specimen, which indicated that from mid-thigh to the feet, there was bare skin devoid of scales, and that a flap of skin connect the upper thigh to the torso. This latter structure is similar to that found in modern birds, including ostriches, but was positioned higher above the knee in Ornithomimus than in birds.[7]

History of discovery

First species named

The history of Ornithomimus classification, and the classification of ornithomimids in general, has been complicated. The type species, Ornithomimus velox, was first named by O.C. Marsh in 1890, based on syntypes YPM 542 and YPM 548, a partial hindlimb and forelimb found on 30 June 1889 by George Lyman Cannon in the Denver Formation of Colorado. The generic name means "bird mimic", derived from Greek ὄρνις, ornis, "bird", and μῖμος, mimos, "mimic", in reference to the bird-like foot. The specific name means "swift" in Latin.[8] Simultaneously, Marsh named two other species: Ornithomimus tenuis, based on specimen USNM 5814, and Ornithomimus grandis. Both consist of fragmentary fossils found by John Bell Hatcher in Montana of which it is today understood they represent tyrannosauroid material. At first Marsh assumed Ornithomimus was an ornithopod but this changed when Hatcher found specimen USNM 4736, a partial ornithomimid skeleton, in Wyoming, which Marsh named Ornithomimus sedens in 1892. On that occasion also Ornithomimus minutus was created based on specimen YPM 1049, a metatarsus,[9] since recognized as belonging to the Alvarezsauridae.[10]

A sixth species, Ornithomimus altus, was named in 1902 by Lawrence Lambe, based on specimen CMN 930, hindlimbs found in 1901 in Alberta,[11] but this was in 1916 renamed to a separate genus, Struthiomimus, by Henry Fairfield Osborn.[12] In 1920 Charles Whitney Gilmore named Ornithomimus affinis for Dryosaurus grandis Lull 1911,[13] based on indeterminate material. In 1930 Loris Russell renamed Struthiomimus brevetertius Parks 1926 and Struthiomimus samueli Parks 1928 into Ornithomimus brevitertius and Ornithomimus samueli.[14] The same year Oliver Perry Hay renamed Aublysodon mirandus Leidy 1868 into Ornithomimus mirandus,[15] today seen as a nomen dubium. In 1933 William Arthur Parks created a Ornithomimus elegans,[16] today seen as either belonging to Chirostenotes or Elmisaurus. That same year, Gilmore named Ornithomimus asiaticus for material found in Inner Mongolia.[17]

Also in 1933, Charles Mortram Sternberg named the species Ornithomimus edmontonicus for a nearly complete skeleton from the Horseshoe Canyon Formation of Alberta, specimen CMN 8632.[18]

Reclassification by Dale Russell

At first it had been common to name each newly discovered ornithomimid as a species of Ornithomimus. In the sixties, this tendency was still strong as is shown by the fact that Oskar Kuhn renamed Megalosaurus lonzeensis Dollo 1903 from Belgium into Ornithomimus lonzeensis (today understood to be an abelisauroid claw),[19] and Dale Russell in 1967 renamed Struthiomimus currellii Parks 1933 and Struthiomimus ingens Parks 1933 into Ornithomimus currellii and Ornithomimus ingens.[20] At the same time it was usual that workers referred to the entire ornithomimid material as simply "Struthiomimus".[21] To solve this confusion by scientifically testing the separation between Ornithomimus and Struthiomimus, in 1972 Dale Russell published a morphometric study showing that statistical differences in some proportions could be used to distinguish the two. He concluded that Struthiomimus and Ornithomimus were valid genera. In the latter Russell recognised two species: the type species Ornithomimus velox and Ornithomimus edmontonicus even though he had trouble reliably distinguishing it from O. velox. Struthiomimus currellii he considered a younger synonym of Ornithomimus edmontonicus. However, Russell also interpreted the data as indicating that many specimens could not be referred to either Ornithomimus or Struthiomimus. Therefore, he created two new genera. The first was Archaeornithomimus to which Ornithomimus asiaticus and Ornithomimus affinis were assigned, becoming an Archaeornithomimus asiaticus and an Archaeornithomimus affinis. The second genus was Dromiceiomimus, meaning "Emu mimic" from the old generic name for the emu, Dromiceius. Russell assigned several former Ornithomimus species named during the 20th century, including O. brevitertius and O. ingens, to the new genus as Dromiceimimus brevitertius. He renamed Ornithomimus samueli into a second Dromiceiomimus species: Dromiceiomimus samueli.[22]

Misassigned to Ornithomimus

Two tibiae from the Navesink Formation of New Jersey were named Coelosaurus antiquus ("antique hollow lizard") by Joseph Leidy in 1865. The tibiae were first attributed to Ornithomimus in 1979 by Donald Baird and John R. Horner as Ornithomimus antiquus.[23] Normally, this would have made Ornithomimus a junior synonym of Coelosaurus, but Baird and Horner discovered that the name "Coelosaurus" was preoccupied by a dubious taxon based on a single vertebra, named Coelosaurus by an anonymous author now known to be Richard Owen in 1854.[24] Baird referred several other specimens from New Jersey and Maryland to O. antiquus. Beginning in 1997, Robert M. Sullivan regarded O. velox and O. edmontonicus as junior synonyms of O. antiquus. Like Russell, he considered the former two species indistinguishable from each other, and noted that they both shared distinctive features with O. antiquus.[25] However, David Weishampel (2004) considered "C." antiquus to be indeterminate among ornithomimosaurs, and therefore a nomen dubium.[24] An SVP 2012 abstract agreed with Weishampel by noting that Coelosaurus differs from Gallimimus and Ornithomimus in the features of the tibiae.[26]

In 1988 Gregory S. Paul renamed Gallimimus bullatus into Ornithomimus bullatus.[27] This has found no acceptance among other workers and presently the name is not used by Paul himself.

Present interpretations

Even after Russell's study, various researchers have found reasons to lump some or all of these species back into Ornithomimus in various combinations. In 2004, Peter Makovicky, Yoshitsugu Kobayashi and Phil Currie studied Russell's 1972 proportional statistics to re-analyze ornithomimid relationships in light of new specimens. They concluded that there was no justification to separate Dromiceiomimus from Ornithomimus, sinking Dromiceiomimus as a synonym of O. edmontonicus.[28] However, they did not include the type species of Ornithomimus, O. velox, in this analysis. The same team further supported the synonymy between Dromiceiomimus and O. edmontonicus in a 2006 lecture at the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology annual meeting,[29] and their opinion has been followed by most later authors.[30] Makovicky's team also considered Dromiceiomimus samueli to be a junior synonym of O. edmontonicus, though Longrich later suggested it may belong to a distinct, unnamed species from the Dinosaur Park Formation which have yet to be described.[30] Longrich called the species Ornithomimus samueli in a faunal list for the Dinosaur Park Formation.[31]

Apart from O. edmontonicus dating to the early Maastrichtian, two other species are presently considered to be possibly valid, both from the late Maastrichtian. O. sedens was named by Marsh in 1891 from partial remains found in the Lance Formation of Wyoming, only one year after the description of O. velox. Dale Russell, in his 1972 revision of ornithomimids, could not determine which genus it actually belonged to, though he speculated that it may be intermediate between Struthiomimus and Dromiceiomimus. In 1985 he considered it a species of Ornithomimus.[32] Although it has since been referred to mainly as Struthiomimus sedens, based on complete specimens from Montana (as well as some fragments from Alberta and Saskatchewan), these yet have to be described and compared to the O. sedens holotype.[30]

The other is the original type species: O. velox, at first known from very limited remains. Additional specimens referred to O. velox have been described from the Denver Formation and from the Ferris Formation of Wyoming.[33] One specimen attributed to O. velox (MNA P1 1762A) from the Kaiparowits Formation of Utah, was described in 1985.[32] Re-evaluation of this specimen by Lindsay Zanno and colleagues in 2010, however, cast doubt on its assignment to O. velox, and possibly even to Ornithomimus.[34] This conclusion was supported by a 2015 re-description of O. velox, which found that only the holotype specimen was confidently referable to that species. The authors of this study tentatively referred to the Kaiparowits specimen as Ornithomimus sp., along with all of the specimens from the Dinosaur Park Formation.[1]

Classification

In 1890 Marsh assigned Ornithomimus to the Ornithomimosauria, a classification that is still common. Modern cladistic studies indicate a derived position in the ornithomimids; these however have only included O. edmontonicus in their analyses. The relationships between O. edmontonicus, O. velox and O. sedens have not been published.

The following cladogram is based on Xu et al., 2011:[35]

| Ornithomimidae |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |

Paleobiology

The diet of Ornithomimus is still debated. As theropods, ornithomimids might have been carnivorous but their body shape would also have been suited for a partly or largely herbivorous lifestyle. Suggested food includes insects, crustaceans, fruit, leaves, branches, eggs, and the meat of lizards and small mammals.[3]

Ornithomimus had legs that seem clearly suited for rapid locomotion, with the tibia about 20% longer than the femur. The large eye sockets suggest a keen visual sense, and also suggest the possibility that they were nocturnal.[36]

In a 2001 study conducted by Bruce Rothschild and other paleontologists, 178 foot bones referred to Ornithomimus were examined for signs of stress fracture, but none were found.[37]

See also

References

- 1 2 Claessens, L. & Mark A. Loewen, M.A. (2015). A redescription of Ornithomimus velour Marsh, 1890 (Dinosauria, Theropoda). Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology (advance online publication). doi:10.1080/02724634.2015.1034593

- ↑ "Ornithomimus". Oxford Dictionaries. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 2016-01-21.

- 1 2 "Dromiceiomimus." In: Dodson, Peter & Britt, Brooks & Carpenter, Kenneth & Forster, Catherine A. & Gillette, David D. & Norell, Mark A. & Olshevsky, George & Parrish, J. Michael & Weishampel, David B. The Age of Dinosaurs. Publications International, LTD. p. 140. ISBN 0-7853-0443-6.

- ↑ Makovicky, P.J., Kobayashi, Y., and Currie, P.J. (2004). "Ornithomimosauria." In Weishampel, D.B., Dodson, P., & Osmólska, H. (eds.), The Dinosauria (second edition). University of California Press, Berkeley: 137-150.

- ↑ Zelenitsky, D. K.; Therrien, F.; Erickson, G. M.; Debuhr, C. L.; Kobayashi, Y.; Eberth, D. A.; Hadfield, F. (2012). "Feathered Non-Avian Dinosaurs from North America Provide Insight into Wing Origins". Science. 338 (6106): 510–514. Bibcode:2012Sci...338..510Z. doi:10.1126/science.1225376. PMID 23112330.

- ↑ Christian Foth; Helmut Tischlinger; Oliver W. M. Rauhut (2014). "New specimen of Archaeopteryx provides insights into the evolution of pennaceous feathers". Nature. 511 (7507): 79–82. Bibcode:2014Natur.511...79F. doi:10.1038/nature13467. PMID 24990749.

- ↑ Van Der Reest, Aaron J.; Wolfe, Alexander P.; Currie, Philip J. (2016). "A densely feathered ornithomimid (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the Upper Cretaceous Dinosaur Park Formation, Alberta, Canada". Cretaceous Research. 58: 108. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2015.10.004.

- ↑ O.C. Marsh, 1890, "Description of new dinosaurian reptiles", The American Journal of Science, series 3 39: 81-86

- ↑ O.C. Marsh, 1892, "Notice of new reptiles from the Laramie Formation", American Journal of Science 43: 449-453

- ↑ Holtz, Thomas R. Jr. (2011) Dinosaurs: The Most Complete, Up-to-Date Encyclopedia for Dinosaur Lovers of All Ages, Winter 2010 Appendix.

- ↑ Lambe, L., 1902, "New genera and species from the Belly River Series (mid-Cretaceous)", Geological Survey of Canada Contributions to Canadian Palaeontology 3(2): 25-81

- ↑ H.F. Osborn, 1916, "Skeletal adaptations of Ornitholestes, Struthiomimus, Tyrannosaurus", Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 35(43): 733-771

- ↑ Gilmore, C.W., 1920, "Osteology of the carnivorous Dinosauria in the United States National Museum with special reference to the genera Antrodemus (Allosaurus) and Ceratosaurus, United States National Museum Bulletin 110: l-154

- ↑ Russell, L.S., 1930, "Upper Cretaceous dinosaur faunas of North America", Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, 69(4): 133-159

- ↑ Hay, O.P., 1930, Second Bibliography and Catalogue of the Fossil Vertebrata of North America. Carnegie Institution of Washington. 390(II): 1-1074

- ↑ Parks, W.A., 1933, "New species of dinosaurs and turtles from the Upper Cretaceous formations of Alberta", University of Toronto Studies, Geological Series, 34: 1-33

- ↑ Gilmore, C.W., 1933, "On the dinosaurian fauna of the Iren Dabasu Formation", Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History, 67: 23-78

- ↑ Sternberg, C.M., 1933, "A new Ornithomimus with complete abdominal cuirass", The Canadian Field-Naturalist 47(5): 79-83

- ↑ Kuhn, O., 1965, "Saurischia (Supplementum 1)". In: Fossilium Catalogus 1. Animalia. 109: 1-94

- ↑ Russell, D.A. and Chamney, T.P., 1967, "Notes on the biostratigraphy of dinosaurian and microfossil faunas in the Edmonton Formation (Cretaceous), Alberta", National Museum of Canada Natural History Papers, 35: 1-22

- ↑ Norman, D., 1985, The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs, Crescent Books, New York, p. 48

- ↑ Russell, D. (1972). "Ostrich dinosaurs from the Late Cretaceous of western Canada." Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences, 9: 375-402.

- ↑ Baird D., and Horner, J., 1979, "Cretaceous dinosaurs of North Carolina", Brimleyana 2: 1-28

- 1 2 Weishampel, D.B.(2004). "Another Look at the Dinosaurs of the East Coast of North America. En (Colectivo Arqueológico-Paleontológico Salense, Ed.)." Actas de las III Jornadas sobre Dinosaurios y su Entorno. 129-168. Salas de los Infantes, Burgos, España.

- ↑ Sullivan, (1997). "A juvenile Ornithomimus antiquus (Dinosauria: Theropoda: Ornithomimosauria), from the Upper Cretaceous Kirtland Formation (De-na-zin Member), San Juan Basin, New Mexico." New Mexico Geological Society Guidebook, 48th Field Conference, Mesozoic Geology and Paleontology of the Four Corners Region. 249-254.

- ↑ Brusatte, Choiniere, Benson, Carr and Norell, 2012. Theropod dinosaurs from the Late Cretaceous of Eastern North America: Anatomy, systematics, biogeography and new information from historic specimens. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. Program and Abstracts 2012, 70.

- ↑ Paul, G.S., 1988, Predatory Dinosaurs of the World. Simon & Schuster: New York. 464 pp

- ↑ Makovicky, Kobayashi and Currie (2004). "Ornithomimosauria." In Weishampel, Dodson and Osmolska (eds.), The Dinosauria Second Edition. University of California Press. 861 pp.

- ↑ Kobayashi, Makovicky and Currie (2006). "Ornithomimids (Theropoda: Dinosauria) from the Late Cretaceous of Alberta, Canada." Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 26(3): 86A.

- 1 2 3 Longrich, N. (2008). "A new, large ornithomimid from the Cretaceous Dinosaur Park Formation of Alberta, Canada: Implications for the study of dissociated dinosaur remains." Palaeontology, 51(4): 983-997.

- ↑ Longrich, N. R. (2014). "The horned dinosaurs Pentaceratops and Kosmoceratops from the upper Campanian of Alberta and implications for dinosaur biogeography". Cretaceous Research, 51: 292. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2014.06.011

- 1 2 DeCourten and Russell, D. (1985). "A specimen of Ornithomimus velox (Theropoda, Ornithomimidae) from the terminal Cretaceous Kaiparowits Formation of southern Utah." Journal of Paleontology, 59(5): 1091-1099.

- ↑ Lillegraven and Eberle (1999). "Vertebrate faunal changes through Lancian and Puercan time in southern Wyoming." Journal of Paleontology, 73(4): 691-710.

- ↑ Zanno, L.E., Weirsma, J.P., Loewen, M.A., Sampson, S.D. and Getty, M.A. (2010). A preliminary report on the theropod dinosaur fauna of the late Campanian Kaiparowits Formation, Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument, Utah." Learning from the Land Symposium: Geology and Paleontology. Washington, DC: Bureau of Land Management.

- ↑ Xu, L.; Kobayashi, Y.; Lü, J.; Lee, Y. N.; Liu, Y.; Tanaka, K.; Zhang, X.; Jia, S.; Zhang, J. (2011). "A new ornithomimid dinosaur with North American affinities from the Late Cretaceous Qiupa Formation in Henan Province of China". Cretaceous Research. 32 (2): 213. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2010.12.004.

- ↑ Palmer, D., ed. (1999). The Marshall Illustrated Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs and Prehistoric Animals. London: Marshall Editions. p. 109. ISBN 1-84028-152-9.

- ↑ Rothschild, B., Tanke, D. H., and Ford, T. L., 2001, Theropod stress fractures and tendon avulsions as a clue to activity: In: Mesozoic Vertebrate Life, edited by Tanke, D. H., and Carpenter, K., Indiana University Press, p. 331-336.

- Claessens, L., Loewen, M. and Lavender, Z. 2011. A reevaluation of the genus Ornithomimus based on new preparation of the holotype of O. velox and new fossil discoveries. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, SVP Program and Abstracts Book, 2011, pp. 90.

- Reisdorf, A.G., and Wuttke, M. 2012. Re-evaluating Moodie's Opisthotonic-Posture Hypothesis in fossil vertebrates. Part I: Reptiles - The taphonomy of the bipedal dinosaurs Compsognathus longipes and Juravenator starki from the Solnhofen Archipelago (Jurassic, Germany). Palaeobiodiversity and Palaeoenvironments, doi:10.1007/s12549-011-0068-y