Olive Oatman

| Olive Oatman | |

|---|---|

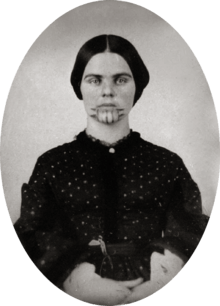

Olive Oatman, circa 1863 | |

| Born |

Olive Ann Oatman 1837 |

| Died |

(aged 65) Sherman, Texas, U.S. |

| Cause of death | Heart attack |

| Resting place | West Hill Cemetery |

| Nationality | American |

| Other names | Olive Oatman Fairchild |

| Citizenship | United States |

| Alma mater | University of the Pacific |

| Spouse(s) | John Brant Fairchild (m. 1865–1903) |

| Children | 1 |

| Parent(s) |

Roys[1] Oatman Mary Ann Oatman |

| Relatives |

Lorenzo (brother)[2] Mary Ann (sister) Roys Oatman, Jr. (brother) Charity Ann (sister) Lucy Ann (sister) Roland (brother) |

Olive Ann Oatman (1837 – March 20, 1903)[3] was a woman from Illinois whose family was killed in 1851, when she was fourteen, in present-day Arizona by a Native American tribe, possibly the Tolkepayas (Western Yavapai); they captured and enslaved her and her sister and later sold them to the Mohave people.[4][5] After several years with the Mohave, during which her sister died of hunger, she returned to American society, five years after being carried off.

In subsequent years, the tale of Oatman came to be retold with dramatic license in the press, in her own "memoir" and speeches, novels, plays, movies and poetry. The story resonated in the media of the time and long afterward, partly owing to the prominent blue tattooing of Oatman's face by the Mohave. Much of what actually occurred during her time with the Native Americans remains unknown.[6]:146-151

Early life

Born into the family of Roys and Mary Ann Oatman, Olive Oatman was one of seven siblings. She grew up in the Mormon religion.

In 1850, the Oatman family joined a wagon train led by James C. Brewster, a member of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church), whose attacks on, and disagreements with, the church leadership in Salt Lake City, Utah, had caused him to break with the followers of Brigham Young in Utah and lead his followers — Brewsterites — to California, which he claimed was the "intended place of gathering" for the Mormons.[7]

The Brewsterite emigrants, numbering between 85 and 93, left Independence, Missouri on August 5, 1850. Dissension caused the group to split near Santa Fe in New Mexico Territory with Brewster following the northern route. Roys Oatman and several other families chose the southern route via Socorro and Tucson. Near Socorro, Roys Oatman assumed command of the party. They reached New Mexico Territory early in 1851 only to find the country and climate wholly unsuited to their purpose. The other wagons gradually abandoned the goal of reaching the mouth of the Colorado River.[7]

The party had reached Maricopa Wells, when they were told that not only was the stretch of trail ahead barren and dangerous, but that the Native Americans ahead were very hostile and that they would risk their lives if they proceeded further. The other families resolved to stay. The Oatman family, eventually traveling alone, was nearly annihilated in what became known as the "Oatman Massacre" on the banks of the Gila River about 80–90 miles east of Yuma, in what is now Arizona.[8]

Oatman massacre

Roys and Mary Oatman had seven children at this time, ranging in age from 17 to one year. On their fourth day out, they were approached by a group of Native Americans, asking for tobacco and food. At some point during the encounter, the Oatman family was attacked by the group, and all were killed except Lorenzo, age 15 (who was clubbed and left for dead), Olive, age 14, and Mary Ann, age 7.[8]

Lorenzo awoke to find his parents and family dead, but no sign of Mary Ann and Olive. He eventually reached a settlement where he was treated. Three days later, Lorenzo, who had rejoined the emigrant train, found the bodies of his slain family; "we buried the bodies of father, mother and babe in one common grave."[9] The men had no way of digging proper graves in the volcanic rocky soil, so they gathered the bodies together and formed a cairn over them. It has been said the remains were reburied several times and finally moved to the river for reinterment by early Arizona colonizer Charles Poston.[10]

Abduction and captivity

Once the attack was complete, the Native Americans took some of the Oatman family's belongings along with the Oatman girls. Although Olive Oatman later identified her captors as Tonto Apaches,[11][12] they were probably Tolkepayas (Western Yavapais)[13]:85 living in a village 60–100 miles from the site of the attack. After arriving at the village, the girls were initially treated in a way that appeared threatening, and Oatman later said she thought they would be killed. However, the girls were used as slaves, to forage for food, lug water and firewood, and other menial tasks; they were frequently beaten and mistreated.

After a year, a group of Mohave Indians visited the village and traded two horses, vegetables, blankets, and other trinkets for the captive girls, after which the girls walked for days to a Mohave village at the confluence of the Gila and Colorado rivers (in what today is Yuma, Arizona). They were immediately taken in by the family of a tribal leader (kohot) whose non-Mohave name was Espianola or Espanesay. The Mohave tribe was more prosperous than the group that had held the girls captive, and both Espanesay's wife Aespaneo and daughter Topeka took an interest in the Oatman girls' welfare. Oatman expressed her deep affection for these two women numerous times over the years after her captivity.[13]:93

Aespaneo arranged for the Oatman girls to be given plots of land to farm. Whether the Oatman girls were truly adopted into that family and the Mohave people is unknown. Oatman later claimed that she and Mary Ann were captives of the Mohave and that she feared to leave. She did not attempt to contact a large group of whites that visited the Mohaves during her period with them,[13]:102 and years later she went to meet with a Mohave leader, Irataba, in New York City and spoke with him of old times.[13]:176-177

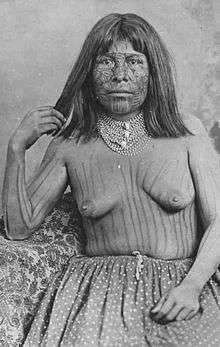

Both Oatman girls were tattooed on their chins and arms[14][15] in keeping with the tribal custom for those who were tribal members. Oatman later claimed (in Stratton's book and in her lectures) that she was tattooed to mark her as a slave of the Mohaves, but this is inconsistent with the Mohave tradition in which such marks were given only to their own people to ensure both that they would enter the land of the dead, and be recognized as Mohaves by their ancestors.[6]:78

During a drought in the region (probably in 1855, according to climate records),[13]:105 the tribe experienced a dire shortage of food supplies and Mary Ann died of starvation, at the age of ten or eleven, along with many Mohaves.

Oatman later spoke with fondness of the Mohaves, whose treatment of her was superior to the treatment she had received when first captured. She most likely considered herself assimilated: she was given a clan name, Oach, and a nickname, Spantsa, a Mohave word having to do with unquenchable lust.[6]:73-74, [16] She remained with the Mohave, choosing not to reveal herself to white railroad surveyors who spent nearly a week in the Mohave Valley trading and socializing with the tribe in February 1854.[6]:88 Because she did not know that Lorenzo had survived the massacre, she believed she had no immediate family, and the Mohave raised her as their own.

Release

When Oatman was 19 years old, Francisco, a Yuma Indian messenger arrived at the village with a message from the authorities at Fort Yuma. Rumors suggested that a white girl was living with the Mohaves and the post commander requested her return (or to know the reason why she did not choose to return). The Mohaves initially sequestered Oatman and resisted the request. At first they denied that Oatman was even white; others over the course of negotiations expressed their affection for Oatman, others their fear of reprisal from whites. Francisco, meanwhile, withdrew to the homes of other nearby Mohaves; shortly thereafter he made a second fervent attempt to persuade the Mohaves to part with Oatman. Trade items were included this time, including blankets and a white horse, and he passed on threats that the whites would destroy the Mohaves if they did not release Oatman.

After some discussion, in which Oatman was this time included, the Mohaves decided to accept these terms, and she was escorted to Fort Yuma in a 20-day journey. Topeka (the daughter of Espianola/Espanesay and Aespaneo) went on the journey with Oatman. Before entering the fort, Oatman was given Western clothing lent by the wife of an army officer, as she was clad in a traditional Mohave skirt with no covering above her waist. Inside the fort, Oatman was surrounded by cheering people.[6]:111

Oatman's childhood friend Susan Thompson, whom she befriended again at this time, stated many years later that she believed Oatman was "grieving" upon her return, because she had been married to a Mohave and given birth to two boys.[13]:152, [17]

Oatman herself, however, denied rumors during her lifetime that she had been either married to a Mohave or was ever raped or sexually mistreated by the Yavapai or Mohave. In Stratton's book she declared that "to the honor of these savages let it be said, they never offered the least unchaste abuse to me". Her nickname, Spantsa ("rotten womb"), however, implied that she was sexually active.[6]:73-74[18] If you continue reading the same source, say other meaning of the nickname.

Within a few days of her arrival at the fort, Oatman discovered her brother Lorenzo was alive and had been looking for her and her sister. Their meeting made headline news across the West.

Later life

In 1857, a pastor named Royal B. Stratton wrote a book about the Oatman girls titled Life Among the Indians. The book sold 30,000 copies, a best-seller for that era.[20] Royalties from the book paid for Oatman and her brother Lorenzo's college education at the University of the Pacific.[21] She went on the lecture circuit to help promote the book.[1]

In November 1865, Oatman married cattleman John B. Fairchild.[22] Though it was rumored that she died in an asylum in New York in 1877, she actually went to live with Fairchild in Sherman, Texas, where they adopted a baby girl, Mamie.[23] Stratton died in Worcester Lunatic Hospital, Jan. 24, 1875.[24]

Death and legacy

Olive Oatman Fairchild died of a heart attack on March 20, 1903, at the age of 65. She is buried at the West Hill Cemetery in Sherman, Texas.[25]

The town of Oatman, Arizona, a ghost town renewed by tourists from a nearby gambling town, is named in her honor.[26]

In 1965, the actress Shary Marshall played Oatman, with Tim McIntire as her brother, Lorenzo, and Ronald W. Reagan as Lieutenant Colonel Burke, in "The Lawless Have Laws" episode of the syndicated western series Death Valley Days, hosted by Reagan near the end of his acting career. In the storyline, Burke leads Lorenzo in a search for his sister, whom he has not seen in five years since an Indian raid on their family.[27][6]:201

The character of Eva portrayed by Robin McLeavy in the AMC television series Hell on Wheels is very loosely based on Olive Oatman, but outside of being captured by a group of Indians and bearing the distinctive blue chin tattoo, and being raised Mormon there are very few similarities between the character of Eva and the actual life of Olive Oatman.[28]

Novelist Elmore Leonard based a short story, The Tonto Woman, on a white captive woman who was tattooed in the manner of Oatman.[6]:203

In an episode of the series The Ghost Inside my Child: The Wild West and Tribal Quest, a southern American Baptist family claims that their daughter Olivia says she is the reincarnation of Olive Oatman.[29]

References

- 1 2 "Fairchild, Olive Ann Oatman". Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved August 10, 2012.

- ↑ Lorenzo Oatman - geni.com

- ↑ geni.com

- ↑ Braatz, Timothy (2003). Surviving Conquest. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press. pp. 253–4.

- ↑ The Oatman Massacre: A Tale of Desert Captivity and Survival

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Mifflin, Margot. The Blue Tattoo: The Life of Olive Oatman. 2009.

- 1 2 James, Edward T.; James, Janet Wilson; Boyer, Paul S. (1971). Notable American Women, 1607-1950: A Biographical Dictionary. Harvard University Press. pp. 646–647. ISBN 978-0-674-62734-5.

- 1 2 Rowe, Jeremy (January 2011). Early Maricopa County: 1871-1920. Arcadia Publishing. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-7385-7416-5.

- ↑ The Tucson Citizen, September 26, 1913

- ↑ Baker (1981). "Mapping the Southwest". The American West. American West Management Corporation. 18: 48–53.

- ↑ History of Mojave Indians to 1860 - By: Fort Mojave Indian Tribe

- ↑ Profiles in Mojave Desert History - Olive Oatman

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Brian McGinty. The Oatman Massacre: A Tale of Desert Captivity and Survival. 2004.

- ↑ https://bodiesontheedge.files.wordpress.com/2013/12/mohavewomantattoos.jpg

- ↑ Mohave. Woman with chin tattoos, ca. 1900., Tribal Tattooing in California and the American Southwest by Lars Krutak

- ↑ The Blue Tattoo

- ↑ Richard H. Dillon. Tragedy at Oatman Flat: Massacre, Captivity, Mystery. American West 18, no. 2 (1981), pages 46-59

- ↑ Lawrence, Deborah; Lawrence, Jon (13 September 2012). Violent Encounters: Interviews on Western Massacres. University of Oklahoma Press. pp. 27–28. ISBN 978-0-8061-8434-0.

- ↑ Tintype portraits of Olive Oatman and Lorenzo D. Oatman held in the collection of the Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library at Yale University

- ↑ Stratton, Royal B. (1857). Life among the Indians: Captivity of the Oatman girls. San Francisco: Whitton, Towne & Co.'s Excelsior Steam Power Presses.

- ↑ Olive Oatman, ca. 1860, by Loryea & Macaulay, Souvenir Photographic Studio 26 south first street san jose - History San José Silicon Valley History Online Collection

- ↑ Story of Olive Ann Oatman is told - Herald Democrat

- ↑ "10 Myths About Olive Oatman". Margot Mifflin. Retrieved 2013-03-26.

- ↑ Stratton, Royal Byron, 1827-1875 - LC Linked Data Service - Library of Congress

- ↑ Ashby, Linda (2011). Sherman. Arcadia Publishing. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-7385-7983-2.

- ↑ Varney, Philip (1994). Arizona Ghost Towns and Mining Camps. Arizona Department of Transportation, State of Arizona. p. 1905. ISBN 978-0-916179-44-1.

- ↑ "The Lawless Have Laws on Death Valley Days". Internet Movie Data Base. Retrieved August 27, 2015.

- ↑ "Character Profile for Eva". Internet Movie Data Base. Retrieved August 3, 2015.

- ↑ "The Wild West and Tribal Quest". The Ghost Inside my Child. Season 1. Episode 3. 30 August 2014. Lifetime.

Further reading

- Leo Banks, Stalwart Women: Frontier Stories of Indomitable Spirit (ISBN 0-916179-77-X)

- Brian McGinty, The Oatman Massacre: A Tale of Desert Captivity and Survival (ISBN 0-8061-3667-7)

- Margot Mifflin, The Blue Tattoo: The Life of Olive Oatman (ISBN 978-0-8032-1148-3)

- "Oatman Cookbook, History and Ghost Stories" - Written by the residents of modern-day Oatman.

- Royal B. Stratton: Captivity of the Oatman Girls: Being an Interesting Narrative of Life among the Apache and Mohave Indians, 1857, archive.org.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Olive Oatman. |

- Olive Oatman at Find a Grave

- http://www.wikitree.com/genealogy/OATMAN

- The Blue Tattoo excerpt

- Film: The lament of Olive Oatman

- blue in the face - arizona highways

- The girl with the tattooed face: The story of Olive Oatman's famous capture. by Chris Wild

- Olive Oatman by Benjamin F. Powelson (58 State St, Rochester, NY), ca. 1863

- mohave woman tattoos

- Marks of Transformation: Tribal Tattooing in California & the American Southwest by Lars Krutak

- Olive Oatman , tattoo covered

- Retrobituary: Olive Oatman, the Pioneer Girl Who Became a Marked Woman - Mental Floss