Olduvai Gorge

| Olduvai Gorge | |

|---|---|

| Oldupai Gorge | |

| |

Olduvai Gorge Olduvai Gorge in Tanzania | |

| Long-axis length | 48 kilometres (30 mi) |

| Geography | |

| Coordinates | 2°59′37″S 35°21′04″E / 2.993613°S 35.35115°ECoordinates: 2°59′37″S 35°21′04″E / 2.993613°S 35.35115°E |

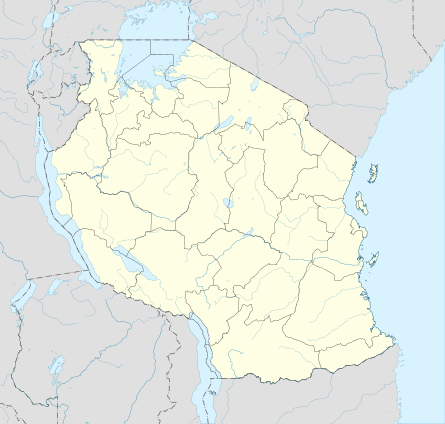

Olduvai Gorge, or Oldupai Gorge, in Tanzania is one of the most important paleoanthropological sites in the world; it has proven invaluable in furthering understanding of early human evolution. A steep-sided ravine in the Great Rift Valley that stretches across East Africa, it is about 48 km (30 mi) long, and is located in the eastern Serengeti Plains in the Arusha Region not far, about 45 kilometres (28 miles), from Laetoli, another important archaeological site of early human occupation. The British/Tanzanian paleoanthropologist-archeologist team Mary and Louis Leakey established and developed the excavation and research programs at Olduvai Gorge which achieved great advances of human knowledge and world-renowned status.

Homo habilis, probably the first early human species, occupied Olduvai Gorge approximately 1.9 million years ago (mya); then came a contemporary australopithecine, Paranthropus boisei, 1.8 mya, and then Homo erectus, 1.2 mya. Homo sapiens is dated to have occupied the site 17,000 years ago.

The site is significant in showing the increasing developmental and social complexities in the earliest humans, or hominins, largely as revealed in the production and use of stone tools. And prior to tools, the evidence of scavenging and hunting—highlighted by the presence of gnaw marks that predate cut marks—and of the ratio of meat versus plant material in the early hominin diet. The collecting of tools and animal remains in a central area is evidence of developing social interaction and communal activity. All these factors indicate increase in cognitive capacities at the beginning of the period of hominids transitioning to hominin—that is, to human—form and behavior.

History

Research

German neurologist Wilhelm Kattwinkel traveled to Olduvai Gorge in 1911,[1] where he observed many fossil bones of an extinct three-toed horse. Inspired by Kattwinkel's discovery, German geologist Hans Reck led a team to Olduvai in 1913. There, he found hominin remains, but the start of World War I halted his research. In 1929, Louis Leakey visited Reck and viewed the Olduvai fossils; he became convinced that Olduvai Gorge held critical information on human origins, and he proceeded to mount an expedition there.

Louis and Mary Leakey are responsible for most of the excavations and discoveries of the hominin fossils in Olduvai Gorge. Their finds and research in East Africa and the prior work of Raymond Dart and Robert Broom in South Africa eventually convinced most paleoanthropologists that humans did indeed evolve in Africa. In 1959, at the Frida Leakey Korongo (FLK) site (named after Louis' first wife), Mary Leakey found remains of the robust australopithecine Zinjanthropus boisei (now known as Paranthropus boisei)—which she dubbed the "Nutcracker Man"; its age, 1.75 million years, radically altered accepted ideas about the time scale of human evolution. In addition to an abundance of faunal remains the Leakeys found more than 2,000 stone tools and lithic flakes, most of which they classified as Oldowan (of Olduvai) tools. In 1960, the Leakeys' son Jonathan found a jaw fragment that proved to be the first fossil specimen of Homo habilis.

Researchers have dated Olduvai Gorge layers with radiometric dating of the embedded artifacts, using potassium-argon and argon-argon methodology. Geologist Richard L. Hay studied the Olduvai Gorge and surrounding region between 1961 and 2002. His findings revealed that the site once contained a large lake, with shores covered by deposits of volcanic ash. Around 500,000 years ago, seismic activity diverted a nearby stream which proceeded to cut down through the sediments, revealing seven main layers in the walls of the gorge.

The name Olduvai is a misspelling of Oldupai Gorge, which was adopted as the official name in 2005. Oldupai is the Maasai word for the wild sisal plant Sansevieria ehrenbergii, which grows in the gorge.[2]

Occupation

Homo habilis occupied Olduvai from 1.9 mya. The australopithecine Paranthropus boisei was found to occupy the site from approximately 1.8 until 1.2 mya. Remains of Homo erectus have been dated at the site from 1.2 mya until 700,000 years ago. Homo sapiens came to occupy the gorge some 17,000 years ago.

Significance

Toolmaking

In the 1930s, as Mary and Louis Leakey opted to search for stone tools in East Africa, many, if not most, scholars were skeptical that Africa was the place where humans evolved. The Leakeys soon turned the evidence that confirmed their intuition. They found stone tools in the lowest (oldest) geological beds (see below). These tools presented both shaped edges and sharp points; and lithic flakes—struck off the core stone in the intentional shaping of those points and edges—were found in copious amounts.

The Leakeys mapped locations where the tools were found and the sites where the unprocessed materials (stone cobbles) originated. They determined that some tools were found to have been transported up to nine miles from the place of origin, which suggested cognitive capacities to think and plan, and to execute, with abstract thought and purpose of mind. The Oldowan tools were found in the same stratum as the Australopithecus specimen, but the large number of other hominin fossils dating back to two mya complicated the discussion as to which species was, in fact, the toolmaker.

The first species found by the Leakeys, Zinjanthropus boisei or Australopithecus boisei (renamed and still debated as Paranthropus boisei), featured a sagittal crest and large molars, which attributes suggested the species engaged in heavy chewing, indicating a diet of tough plant material, including tubers, nuts, and seeds—and possibly large quantities of grasses and sedges.[3]

Conversely, the Leakeys' 1960s finds presented different characteristics. The skull lacked of a sagittal crest and the braincase was much more rounded, suggesting it was not australopithecine. The larger braincase suggested a larger brain capacity than that of Australopithecus boisei. These important differences indicated a different species, which eventually was named Homo habilis. Its larger brain capacity and decreased teeth size pointed to Homo as the probable toolmaker.

The oldest tools at Olduvai, found at the lowest layer and classified as Oldowan, consists of pebbles chipped on one edge.[4] Above this layer, and later in time, are the true hand-axe industries, the Chellean and the Acheulean. Higher still (and later still) are located Levallois artifacts, and finally the Stillbay implements.[4] Oldowan tools in general are called "pebble tools" because the blanks chosen by the stone knapper already resembled, in pebble form, the final product.[5] Mary Leakey classified the Oldowan tools according to usage; she developed Oldowan A,B, and C categories, linking them to Modes 1, 2, and 3 assemblages classified according to mode of manufacture. Her work remains a foundation for assessing local, regional, and continental changes in stone tool-making during the early Pleistocene, and aids in assessing which hominins were responsible for the several changes in stone tool technology over time.[6]

It is not known for sure which hominin species was first to create Oldowan tools. The emergence of tool culture has also been associated with the pre-Homo species Australopithecus garhi,[7] and its flourishing is associated with the early species Homo habilis and Homo ergaster. Beginning 1.7 million years ago, early Homo erectus apparently inherited Oldowan technology and refined it into the Acheulean industry.[8]

Dating of beds

Oldowan tools occur in Beds I–IV at Olduvai Gorge. Bed I, dated 1.85 to 1.7 mya, contains Oldowan tools and fossils of Paranthropus boisei and Homo habilis, as does Bed II, 1.7 to 1.2 mya. H. habilis gave way to Homo erectus at about 1.6 mya, but P. boisei persisted. Oldowan tools continue to Bed IV at 800,000 to 600,000 before present (BP). A significant change took place between Beds I and II at about 1.5 mya. Flake size increased, the length of bifacial edges (as opposed to single-face edges) occurred more frequently and their length increased, and signs of battering on other artifacts increased. Some likely implications of these factors, among others, are that after this pivotal time hominins used tools more frequently, became better at making tools, and transported tools more often.[9]

Unprocessed materials

Lava and quartz were used to make tools in Olduvai Gorge. Only in the period 1.65 to 1.53 ma was chert used, and it presents a significant difference in appearance among the assemblages of Olduvai Gorge.[9]

Hunters or scavengers?

Though substantial evidence of hunting and scavenging has been discovered at Olduvai Gorge, it is believed by archaeologists that hominins inhabiting the area between 1.9 and 1.7 mya spent the majority of their time gathering wild plant foods, such as berries, tubers and roots. The earliest hominins most likely did not rely on meat for the bulk of their nutrition. Speculation about the amount of meat in their diets is inferred from comparative studies with a close relative of early hominins: the modern chimpanzee. The chimpanzee's diet in the wild consists of only about five percent as meat. And the diets of modern hunter-gatherers do not include a large amount of meat. That is, most of the calories in both groups' diets came from plant sources. Thus, it can be assumed that early hominins had similar diet proportions, (see the middle-range theory or bridging arguments—bridging arguments are used by archaeologists to explain past behaviors, and they include an underlying assumption of uniformitarianism.)

Much of the information about early hominins comes from tools and debris piles of lithic flakes from such sites as FLK-Zinjanthropus in Olduvai Gorge. Early hominins selected specific types of rocks that would break in a predictable manner when "worked", and carried these rocks from deposits several miles away. Archaeologists such as Fiona Marshall fitted rock fragments back together like a puzzle. She states in her article "Life in Olduvai Gorge" that early hominins, "knew the right angle to hit the cobble, or core, in order to successfully produce sharp-edged flakes ...". She noted that selected flakes then were used to cut meat from animal carcasses, and shaped cobbles (called choppers) were used to extract marrow and to chop tough plant material.

Bone fragments of birds, fish, amphibians, and large mammals were found at the FLK-Zinj site, many of which were scarred with marks. These likely were made by hominins breaking open the bones for marrow, using tools to strip the meat, or by carnivores having gnawed the bones. Since several kinds of marks are present together, some archaeologists including Lewis Binford think that hominins scavenged the meat or marrow left over from carnivore kills. Others like Henry Bunn believe the hominins hunted and killed these animals, and carnivores later chewed the bones.[10] This issue is still debated today, but archaeologist Pat Shipman provided evidence that scavenging was probably the more common practice; she published that the majority of carnivore teeth marks came before the cut marks. Another finding by Shipman at FLK-Zinj is that many of the wildebeest bones found there are over-represented by adult and male bones; and this may indicate that hominins were systematically hunting these animals as well as scavenging them. The issue of hunting versus gathering at Olduvai Gorge is still a controversial one.[11]

Hominid fossils found at Olduvai Gorge

Gallery

The oldest object in the British Museum[12]

The oldest object in the British Museum[12] The spot where the first P. boisei was discovered in Tanzania

The spot where the first P. boisei was discovered in Tanzania Oldowan stone chopper

Oldowan stone chopper- About 1.8 million years old

See also

References

- ↑ Maier, Gerhard, African Dinosaurs Unearthed: The Tendaguru Expeditions, Indiana University Press, 2003, p. 116 ISBN 978-0253342140

- ↑ Oldupai Gorge, Base Camp Tanzania

- ↑ Macho, Gabriele A. (2014). "Baboon Feeding Ecology Informs the Dietary Niche of Paranthropus boisei". PLoS ONE. 9 (1): 84942. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...984942M. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0084942. PMC 3885648

. PMID 24416315.

. PMID 24416315. - 1 2 Langer, William L., ed. (1972). An Encyclopedia of World History (5th ed.). Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Company. p. 9. ISBN 0-395-13592-3.

- ↑ Napier, John. 1960. "Fossil Hand Bones from Olduvai Gorge." in Nature", December 17th edition.

- ↑ Barham, Lawrence; Mitchell, Peter (2008). The First Aftricans. Cambridge University Press. p. 126.

- ↑ De Heinzelin, J; Clark, JD; White, T; Hart, W; Renne, P; Woldegabriel, G; Beyene, Y; Vrba, E (1999). "Environment and behavior of 2.5-million-year-old Bouri hominids". Science. 284 (5414): 625–9. doi:10.1126/science.284.5414.625. PMID 10213682.

- ↑ Richards, M.P. (December 2002). "A brief review of the archaeological evidence for Palaeolithic and Neolithic subsistence". European Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 56 (12): 1270–1278. doi:10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601646. PMID 12494313 .

- 1 2 Kimura, Yuki. C (2002). Examining time trends in the Oldowan technology at Beds I and II, Olduvai Gorge. 43. Journal of Human Evolution.

- ↑ Bunn, Henry (2007). Peter Ungar, ed. Meat Made Us Human. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 191–211. ISBN 0195183460.

- ↑ Ungar, Peter (2007). Peter Ungar, ed. Evolution of the Human Diet. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195183460.

- ↑ "A History of the World in 100 Objects". The British Museum. Retrieved 18 May 2016.

Further reading

- Cole, Sonia (1975). Leakey's Luck. Harcourt Brace Jovanvich, New York.

- Colin Renfrew and Paul Bahn Archaeology Essentials (2007). Archaeology Essentials. 2nd Edition. Thames & Hudson Ltd, London.

- Deocampo, Daniel M. (2004). Authigenic clays in East Africa: Regional trends and paleolimnology at the Plio-Pleistocene boundary, Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania. Journal of Paleolimnology 31:1-9.

- Deocampo, Daniel M., Blumenschine, R.J., and Ashley, G.M. (2002). Freshwater wetland diagenesis and traces of early hominids in the lowermost Bed II (~1.8 myr) playa lake-margin at Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania. Quaternary Research 57:271-281.

- Hay, Richard L. (1976). "Geology of the Olduvai Gorge." University of California Press, 203 pp.

- Gengo, Michael F. (2009). Evidence of Human Evolution, Interpreting. Encyclopedia of Time: Science, Philosophy, Theology, & Culture.SAGE Publications. 5 Dec. 2011.

- Young, Lisa (2 October 2011). Hominin Migrations Out of Africa. Introduction to Prehistoric Archaeology. University of Michigan.

- Tactikos, Joanne Christine (2006). A landscape perspective on the Oldowan from Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania. ISBN 0-542-15698-9.

- Leakey, L.S.B. (1974). By the evidence: Memoirs 1932-1951. Harcourt Brace Jovanavich, New York, ISBN 0-15-149454-1.

- Leakey, M.D. (1971). Olduvai Gorge: Excavations in beds I & II 1960–1963. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- Leakey, M.D. (1984). Disclosing the past. Doubleday & Co., New York, ISBN 0-385-18961-3.

- Marshall, Fiona. (1999). Life in OLDUVAI GORGE. Calliope Sept. 1999: 16. General OneFile. Web. 4 Dec. 2011.

- Young, Lisa (25 September 2011). The First Stone Tool Makers. Introduction to Prehistoric Archaeology. University of Michigan.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Olduvai Gorge. |