Old Prussian language

| Prussian | |

|---|---|

| |

| Region | Prussia (region) |

| Extinct | Early 18th century[1] |

| Revival | Attempted revival, with 50 L2 speakers (no date)[2] |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 |

prg |

| Glottolog |

prus1238[3] |

| Linguasphere |

54-AAC-a |

| |

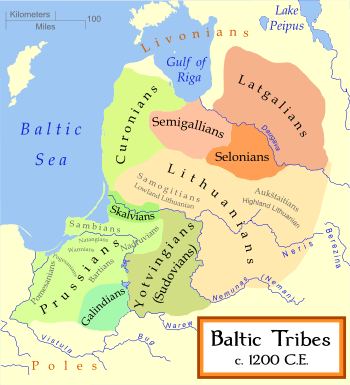

Old Prussian is an extinct Baltic language, once spoken by the Old Prussians, the indigenous peoples of Prussia (not to be confused with the later and much larger German state of the same name), now northeastern Poland and the Kaliningrad Oblast of Russia.

The language is called Old Prussian to avoid confusion with the German dialects Low Prussian and High Prussian, and the adjective Prussian, which is also often used to relate to the later German state.

Old Prussian began to be written down in the Latin alphabet in about the 13th century. A small amount of literature in the language survives.

Original territory

In addition to Prussia proper, the original territory of the Old Prussians might have included eastern parts of Pomerelia (some parts of the region east of the Vistula River). The language might have also been spoken much further east and south in what became Polesia and part of Podlasie with the conquests by Rus and Poles starting in the 10th century and by the German colonisation of the area that began in the 12th century..

Relation to other languages

Old Prussian was closely related to the other extinct Western Baltic languages, namely Curonian, Galindian and Sudovian. It is related to the Eastern Baltic languages such as Lithuanian and Latvian, and more distantly related to Slavic. Compare the Old Prussian semmē, Latvian zeme and Lithuanian žemė.

Old Prussian contained loanwords from Slavic languages (e.g., Old Prussian curtis "hound" just as Lithuanian kùrtas, Latvian kur̃ts come from Slavic (cf. Ukrainian хорт, khort; Polish chart; Czech chrt), as well as a few borrowings from Germanic, including from Gothic (e.g., Old Prussian ylo "awl" as with Lithuanian ýla, Latvian īlens) and from Scandinavian languages.[4]

Groups of people from Germany, Poland,[5][6] Lithuania, France, Scotland,[7] England,[8] and Austria found refuge in Prussia during the Protestant Reformation and thereafter. Such immigration caused a slow decline in the use of Old Prussian, as the Prussians adopted the languages of their more recently arrived co-citizens, particularly German. Baltic Old Prussian probably ceased to be spoken around the beginning of the 18th century due to many of its remaining speakers dying in the famines and bubonic plague epidemics which harrowed the East Prussian countryside and towns from 1709 until 1711.[9] The regional dialect of Low German spoken in Prussia (or East Prussia), called Low Prussian, preserved a number of Baltic Prussian words, such as kurp, from the Old Prussian kurpi, for shoe in contrast to common Low German Schoh (standard German Schuh).

Until the 1930s, when the National Socialist government of Germany began a program of Germanization, and 1945, when the Soviets and Poland annexed East Prussia, one could find Old Prussian river- and place-names there, such as Tawe and Tawellningken.[10]

Different versions of the Lord's Prayer

|

Lord's Prayer after Simon Grunau (Curonian-Latvian)

|

Lord's Prayer after Prätorius (Curonian-Latvian)

|

|

Lord's Prayer in Old Prussian (from the so-called "1st Catechism")

|

Lord's Prayer in Lithuanian dialect of Insterburg (Prediger Hennig)

|

Lord's Prayer in Lithuanian dialect of Nadruvia, corrupted (Simon Prätorius)

- Tiewe musu, kursa tu essi Debsissa,

- Szwints tiest taws Wards;

- Akeik mums twa Walstybe;

- Tawas Praats buk kaip Debbesissa taibant wirszu Sjemes;

- Musu dieniszka May e duk mums ir szen Dienan;

- Atmesk mums musu Griekus, kaip mes pammetam musi Pardokonteimus;

- Ne te wedde mus Baidykle;

- Bet te passarge mus mi wissa Louna (Pikta)

A list of monuments of Old Prussian

- Prussian-language geographical names within the territory of (Baltic) Prussia. Georg Gerullis undertook the first basic study of these names in Die altpreußischen Ortsnamen ("The Old Prussian Place-names"), written and published with the help of Walter de Gruyter, in 1922.

- Prussian personal names.[11]

- Separate words found in various historical documents.

- Vernacularisms in the former German dialects of East and West Prussia, as well as words of Old Curonian origin in Latvian, and West-Baltic vernacularisms in Lithuanian and Belarusian.

- The so-called Basel Epigram, the oldest written Prussian sentence (1369).[12][13] It reads:

| Old Prussian | English |

|---|---|

| Kayle rekyse | Cheers, Sir! |

| thoneaw labonache thewelyse | You are no longer a good little comrade |

| Eg koyte poyte | if you want to drink |

| nykoyte pênega doyte | (but) do not want to give a penny! |

- This jocular inscription was most probably made by a Prussian student studying in Prague (Charles University); found by Stephen McCluskey (1974) in manuscript MS F.V.2 (book of physics Questiones super Meteororum by Nicholas Oresme), fol. 63r, stored in the Basel University library.

- Various fragmentary texts:

- Recorded in several versions by Hieronymus Maletius in Sudovian Nook in the middle of the 16th century, as noted by Vytautas Mažiulis, are:

- Beigeite beygeyte peckolle ("Run, run, devils!")

- Kails naussen gnigethe ("Hello our friend!")

- Kails poskails ains par antres – a drinking toast, reconstructed as Kaīls pas kaīls, aīns per āntran ("A healthy one after a healthy one, one after another!")

- Kellewesze perioth, Kellewesze perioth ("A carter drives here, a carter drives here!")

- Ocho moy myle schwante panicke – also recorded as O hoho Moi mile swente Pannike, O ho hu Mey mile swenthe paniko, O mues miles schwante Panick ("Oh my dear holy fire!")

- A manuscript fragment of the first words of the Pater Noster in Prussian, from the beginning of the 15th century: Towe Nüsze kås esse andangonsün swyntins.

- 100 words (in strongly varying versions) of the Vocabulary by a friar Simon Grunau, a historian of the Teutonic Knights, written ca. 1517–1526 in his Preussische Chronik. Apart from those words Grunau also recorded an expression sta nossen rickie, nossen rickie ("This (is) our lord, our lord").

- The so-called Elbing Vocabulary, which consists of 802 thematically sorted words and their German equivalents. Peter Holcwesscher from Marienburg copied the manuscript around 1400; the original dates from the beginning of the 14th or the end of the 13th century. It was found in 1825 by Fr. Neumann among other manuscripts acquired by him from the heritage of the Elbing merchant A. Grübnau; it was thus dubbed the Codex Neumannianus.

- The three Catechisms[14] printed in Königsberg in 1545, 1545, and 1561 respectively. The first two consist of only 6 pages of text in Old Prussian – the second one being a correction of the first into another Old Prussian dialect. The third catechism, or Enchiridion, consists of 132 pages of text, and is a translation of Luther's Small Catechism by a German cleric called Abel Will, with his Prussian assistant Paul Megott. Will himself knew little or no Old Prussian, and his Prussian interpreter was probably illiterate, but according to Will spoke Old Prussian quite well. The text itself is mainly a word-for-word translation, and Will phonetically recorded Megott's oral translation. Due to this fact, Enchiridion exhibits many irregularities, such as the lack of case agreement in phrases involving an article and a noun, which followed word-for-word German originals as opposed to native Old Prussian syntax.

- Commonly thought of as Prussian, but probably actually Lithuanian (at least the adage, however, has been argued to be genuinely West Baltic, only an otherwise unattested dialect[15]):

- An adage of 1583, Dewes does dantes, Dewes does geitka: the form does in the second instance corresponds to Lithuanian future tense duos ("will give")

- Trencke, trencke! ("Strike! Strike!")

Grammar

With other monuments being merely word lists, the grammar of Old Prussian is reconstructed chiefly on the basis of the three Catechisms. There is no consensus on the number of cases that Old Prussian had, and at least four can be determined with certainty: nominative, genitive, accusative and dative, with different desinences. There are traces of a vocative case, such as in the phrase O Deiwe Rikijs "O God the Lord", reflecting the inherited PIE vocative ending *-e. There was a definite article (stas m., sta f.); three genders: masculine, feminine and neuter, and two numbers: singular and plural. Declensional classes were a-stems, ā-stems (feminine), ē-stems (feminine), i-stems, u-stems, ī/jā-stems, jā/ijā-stems and consonant-stems. Present, future and past tense are attested, as well as optative forms (imperative, permissive), infinitive, and four participles (active/passive present/past).

Revived Old Prussian

A few linguists and philogogists are involved in reviving a reconstructed form of the language from Luther's catechisms, the Elblągian dictionary, place names, and Prussian loan words in the Low Prussian dialect of German. Several dozen people use the language in Lithuania, Kaliningrad, and Poland, including a few children who are natively bilingual. The Prusaspira Society has published their translation of Antoine de Saint-Exupéry's The Little Prince. The book was translated by Piotr Szatkowski (Pīteris Šātkis) and released in 2015. The other efforts of Baltic Prussian societies include development of online dictionaries, learning apps and games. In Kaliningrad Oblast there are also attempts to produce music with lyrics written in the revived Baltic Prussian language.[16][17]

Important in this revival was Vytautas Mažiulis, who died on 11 April 2009, and his pupil Letas Palmaitis, leader of the experiment and author of the web site Prussian Reconstructions.[18] Two late contributors were Prāncis Arellis (Pranciškus Erelis), Lithuania, and Dailūns Russinis (Dailonis Rusiņš), Latvia. After them Twankstas Glabbis from Kaliningrad oblast and Nērtiks Pamedīns from Polish Warmia-Mazuria actively joined.

References

- ↑ Prussian at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015)

- ↑ Old Prussian language at Ethnologue (16th ed., 2009)

- ↑ Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin; Bank, Sebastian, eds. (2016). "Prussian". Glottolog 2.7. Jena: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- ↑ Encyclopædia Britannica article on Baltic languages

- ↑ A Short History of Austria-Hungary and Poland by H. Wickham Steed, et al. Historicaltextarchive.com

"For a time, therefore, the Protestants had to be cautious in Poland proper, but they found a sure refuge in Prussia, where Lutheranism was already the established religion, and where the newly erected University of Königsberg became a seminary for Polish ministers and preachers."

- ↑ Ccel.org, Christianity in Poland

"Albert of Brandenburg, Grand Master of the German Order in Prussia, called as preacher to Konigsberg Johann Briesaman (q.v.), Luther's follower (1525); and changed the territory of the order into a hereditary grand duchy under Polish protection. From these borderlands the movement penetrated Little Poland which was the nucleus for the extensive kingdom. [...] In the mean time the movement proceeded likewise among the nobles of Great Poland; here the type was Lutheran, instead of Reformed, as in Little Poland. Before the Reformation the Hussite refugees had found asylum here; now the Bohemian and Moravian brethren, soon to be known as the Unity of the Brethren (q.v.), were expelled from their home countries and, on their way to Prussia (1547), about 400 settled in Posen under the protection of the Gorka, Leszynski, and Ostrorog families."

- ↑ "Scots in Eastern and Western Prussia, Part III – Documents (3)". Retrieved 2007-02-18.

- ↑ "Elbing" (PDF). Retrieved 2007-02-18.

- ↑ Donelaitis Source, Lithuania

- ↑ Haack, Hermann (1930). Stielers Hand-Atlas (10 ed.). Justus Perthes. p. Plate 9.

- ↑ Reinhold Trautmann, Die altpreußischen Personennamen (The Old Prussian Personal-names). Vandenhoeck und Ruprecht, Göttingen: 1923. Includes the work of Ernst Lewy in 1904.

- ↑ Basel Epigram

- ↑ The Old Prussian Basel Epigram

- ↑ Prussian Catechisms.

- ↑ Hill, Eugen (2004). "Die sigmatischen Modus-Bildungen der indogermanischen Sprachen. Erste Abhandlung: Das baltische Futur und seine Verwandten". International Journal of Diachronic Linguistics and Linguistic Reconstruction (1): 78–79. Retrieved 29 August 2014.

- ↑ "Little Prince Published in Prussian", Culture.PL, 2015/02/17

- ↑ http://www.dangus.net/releases/albumai/043_RomoweRikoito.htm

- ↑ Prussian Reconstructions

Literature

- Georg Heinrich Ferdinand Nesselmann, Forschungen auf dem gebiete der preussischen sprache, Königsberg, 1871.

- G. H. F. Nesselmann, Thesaurus linguae Prussicae, Berlin, 1873.

- E. Berneker, Die preussische Sprache, Strassburg, 1896.

- R. Trautmann, Die altpreussischen Sprachdenkmäler, Göttingen, 1910.

- Wijk, Nicolaas van, Altpreussiche Studien : Beiträge zur baltischen und zur vergleichenden indogermanischen Grammatik, Haag, 1918.

- G. Gerullis, Die altpreussischen Ortsnamen, Berlin-Leipzig, 1922.

- G. Gerullis, Georg: Zur Sprache der Sudauer-Jadwinger, in Festschrift A. Bezzenberger, Göttingen 1927

- R. Trautmann, Die altpreussischen Personnennamen, Göttingen, 1925.

- J. Endzelīns, Senprūšu valoda. – Gr. Darbu izlase, IV sēj., 2. daļa, Rīga, 1982. 9.-351. lpp.

- L. Kilian: Zu Herkunft und Sprache der Prußen Wörterbuch Deutsch–Prußisch, Bonn 1980

- J.S. Vater: Die Sprache der alten Preußen Wörterbuch Prußisch–Deutsch, Katechismus, Braunschweig 1821/Wiesbaden 1966

- J.S. Vater: Mithridates oder allgemeine Sprachenkunde mit dem Vater Unser als Sprachprobe, Berlin 1809

- V. Mažiulis, Prūsų kalbos paminklai, Vilnius, t. I 1966, t. II 1981.

- W. R. Schmalstieg, An Old Prussian Grammar, University Park and London, 1974.

- W. R. Schmalstieg, Studies in Old Prussian, University Park and London, 1976.

- V. Toporov, Prusskij jazyk: Slovar', A – L, Moskva, 1975–1990 (nebaigtas, not finished).

- V. Mažiulis, Prūsų kalbos etimologijos žodynas, Vilnius, t. I-IV, 1988–1997.

- M. Biolik, Zuflüsse zur Ostsee zwischen unterer Weichsel und Pregel, Stuttgart, 1989.

- R. Przybytek, Ortsnamen baltischer Herkunft im südlichen Teil Ostpreussens, Stuttgart, 1993.

- M. Biolik, Die Namen der stehenden Gewässer im Zuflussgebiet des Pregel, Stuttgart, 1993.

- M. Biolik, Die Namen der fließenden Gewässer im Flussgebiet des Pregel, Stuttgart, 1996.

- G. Blažienė, Die baltischen Ortsnamen in Samland, Stuttgart, 2000.

- R. Przybytek, Hydronymia Europaea, Ortsnamen baltischer Herkunft im südlichen Teil Ostpreußens, Stuttgart 1993

- A. Kaukienė, Prūsų kalba, Klaipėda, 2002.

- V. Mažiulis, Prūsų kalbos istorinė gramatika, Vilnius, 2004.

- LEXICON BORVSSICVM VETVS. Concordantia et lexicon inversum. / Bibliotheca Klossiana I, Universitas Vytauti Magni, Kaunas, 2007.

- OLD PRUSSIAN WRITTEN MONUMENTS. Facsimile, Transliteration, Reconstruction, Comments. / Bibliotheca Klossiana II, Universitas Vytauti Magni / Lithuanians' World Center, Kaunas, 2007.

External links

| Old Prussian language test of Wikipedia at Wikimedia Incubator |

| For a list of words relating to Old Prussian language, see the Old Prussian language category of words in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Database of the Old Prussian Linguistic Heritage (Etymological Dictionary of Old Prussian (in Lithuanian) and full textual corpus)

- Frederik Kortlandt: Electronic text editions (contains transcriptions of Old Prussian manuscript texts)

- Bilingual catechism (first page) of 1545

- M. Gimbutas Map Western Balts-Old Prussians