Ohlone people

|

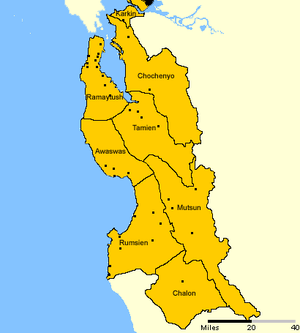

Map of the Costanoan languages and major villages | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

|

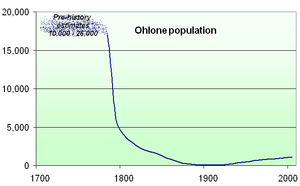

(1770: 10,000–20,000 1800: 3000 1852: 864–1000 2000: 1500–2000+ 2010: 3,853[1]) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| California: San Francisco, Santa Clara Valley, East Bay, Santa Cruz Mountains, Monterey Bay, Salinas Valley | |

| Languages | |

|

Ohlone (Costanoan): Awaswas, Chalon, Chochenyo, Karkin, Mutsun, Ramaytush, Rumsen, Tamyen | |

| Religion | |

| Kuksu | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Ohlone Tribes & Villages |

Ohlone people, named Costanoan by early Spanish colonists (the Spanish word costa means "coast"), are a Native American people of the Northern California coast. When Spanish explorers and missionaries arrived in the late 18th century, the Ohlone inhabited the area along the coast from San Francisco Bay through Monterey Bay to the lower Salinas Valley. At that time they spoke a variety of related languages. The Ohlone languages belonged to the Costanoan sub-family of the Utian language family,[2] which itself belongs to the proposed Penutian language phylum.

The term "Ohlone" has been used in place of "Costanoan" since the 1970s by some descendant groups and by most ethnographers, historians, and writers of popular literature. In pre-colonial times, the Ohlone lived in more than 50 distinct landholding groups, and did not view themselves as a distinct group. They lived by hunting, fishing, and gathering, in the typical ethnographic California pattern. The members of these various bands interacted freely with one another. The Ohlone people practiced the Kuksu religion. Prior to the Gold Rush, the northern California region was one of the most densely populated regions north of Mexico.[3] However, in the years 1769 to 1833, the Spanish missions in California had a negative effect on Ohlone culture, and the Ohlone population declined steeply during this period.

The Ohlone living today belong to one or another of a number of geographically distinct groups, most, but not all, in their original home territory. The Muwekma Ohlone Tribe has members from around the San Francisco Bay Area, and is composed of descendants of the Ohlones/Costanoans from the San Jose, Santa Clara, and San Francisco missions. The Ohlone/Costanoan Esselen Nation, consisting of descendants of intermarried Rumsen Costanoan and Esselen speakers of Mission San Carlos Borromeo, are centered at Monterey. The Amah-Mutsun Tribe are descendants of Mutsun Costanoan speakers of Mission San Juan Bautista, inland from Monterey Bay. Most members of another group of Rumsien language, descendants from Mission San Carlos, the Costanoan Rumsien Carmel Tribe of Pomona/Chino, now live in southern California. These groups, and others with smaller memberships (see groups listed under the heading Present Day below) are separately petitioning the federal government for tribal recognition.

Culture

The Ohlone inhabited fixed village locations, moving temporarily to gather seasonal foodstuffs like acorns and berries. The Ohlone people lived in Northern California from the northern tip of the San Francisco Peninsula down to northern region of Big Sur, and from the Pacific Ocean in the west to the Diablo Range in the east. Their vast region included the San Francisco Peninsula, Santa Clara Valley, Santa Cruz Mountains, Monterey Bay area, as well as present-day Alameda County, Contra Costa County and the Salinas Valley. Prior to Spanish contact, the Ohlone formed a complex association of approximately 50 different "nations or tribes" with about 50 to 500 members each, with an average of 200. Over 50 distinct Ohlone tribes and villages have been recorded. The Ohlone villages interacted through trade, intermarriage and ceremonial events, as well as some internecine conflict. Cultural arts included basket-weaving skills, seasonal ceremonial dancing events, female tattoos, ear and nose piercings, and other ornamentation.[4]

.jpg)

The Ohlone subsisted mainly as hunter-gatherers and in some ways harvesters. "A rough husbandry of the land was practiced, mainly by annually setting of fires to burn-off the old growth in order to get a better yield of seeds—or so the Ohlone told early explorers in San Mateo County." Their staple diet consisted of crushed acorns, nuts, grass seeds, and berries, although other vegetation, hunted and trapped game, fish and seafood (including mussels and abalone from the San Francisco Bay and Pacific Ocean), were also important to their diet. These food sources were abundant in earlier times and maintained by careful work, and through active management of all the natural resources at hand.[5] Animals in their mild climate included the grizzly bear, elk (Cervus elaphus), pronghorn, and deer. The streams held salmon, perch, and stickleback. Birds included plentiful ducks, geese, quail, great horned owls, red-shafted flickers, downy woodpeckers, goldfinches, and yellow-billed magpies. Waterfowl were the most important birds in the people's diet, which were captured with nets and decoys. The Chochenyo traditional narratives refer to ducks as food, and Juan Crespí observed in his journal that geese were stuffed and dried "to use as decoys in hunting others".[6]

Along the ocean shore and bays, there were also otters, whales, and at one time thousands of sea lions. In fact, there were so many sea lions that according to Crespi it "looked like a pavement" to the incoming Spanish.[7]

In general, along the bayshore and valleys, the Ohlone constructed dome-shaped houses of woven or bundled mats of tules, 6 to 20 feet (1.8 to 6 m) in diameter. In hills where redwood trees were accessible, they built conical houses from redwood bark attached to a frame of wood. Residents of Monterey recall Redwood houses. One of the main village buildings, the sweat lodge was low into the ground, its walls made of earth and roof of earth and brush. They built boats of tule to navigate on the bays propelled by double-bladed paddles.[8]

Generally, men did not wear clothing in warm weather. In cold weather, they might don animal skin capes or feather capes. Women commonly wore deerskin aprons, tule skirts, or shredded bark skirts. On cool days, they also wore animal skin capes. Both wore ornamentation of necklaces, shell beads and abalone pendants, and bone wood earrings with shells and beads. The ornamentation often indicated status within their community.[9]

Religion

Ohlone as ethnographers to connect with their past

Researchers are sensitive to limitations in historical knowledge, and careful not to place the spiritual and religious beliefs of all Ohlone people into a single unified worldview.[10] Due to the displacement of Indian people in the Missions between 1769-1833, cultural groups are working as ethnographers to discover for themselves their ancestral history, and what that information tells about them as a cultural group. Their religion is different depending on the band referred to, although they share components of their worldview.[11]

The pre-contact Ohlone practiced Kuksu. They believed that spiritual doctors could heal and prevent illness, and they had a "probable belief in bear shamans". Their spiritual beliefs were not recorded in detail by missionaries. However, some of the villages probably learned and practiced Kuksu, a form of shamanism shared by many Central and Northern California tribes (although there is some question whether the Ohlone people learned Kuksu from other tribes while at the missions). Kuksu included elaborate acting and dancing ceremonies in traditional costume, an annual mourning ceremony, puberty rites of passage, intervention with the spirit world and an all-male society that met in subterranean dance rooms.[12]

Kuksu was shared with other indigenous ethnic groups of Central California, such as their neighbors the Miwok and Esselen, also Maidu, Pomo, and northernmost Yokuts. However Kroeber observed less "specialized cosmogony" in the Ohlone, which he termed one of the "southern Kuksu-dancing groups", in comparison to the Maidu and groups in the Sacramento Valley; he noted "if, as seems probable, the southerly Kuksu tribes (the Miwok, Costanoans, Esselen, and northernmost Yokuts) had no real society in connection with their Kuksu ceremonies."[13]

The conditions upon which the Ohlone joined the Spanish missions are subject to debate. Some have argued that they were forced to convert to Catholicism, while others have insisted that forced baptism was not recognized by the Catholic Church. All who have looked into the matter agree, however, that baptized Indians who tried to leave mission communities were forced to return. The first conversions to Catholicism were at Mission San Carlos Borromeo, alias Carmel, in 1771. In the San Francisco Bay area the first baptisms occurred at Mission San Francisco in 1777. Many first-generation Mission Era conversions to Catholicism were debatably incomplete and "external".[14]

Spirituality and healing

It is apparent that the pre-contact Ohlone had distinguished medicine persons among their tribe. Some of these people healed through the use of herbs, and some were shamans who were believed to heal through their ability to contact the spirit world.[15] Some shamans typically engaged in more ritualistic healing in the form of dancing, ceremony, and singing.[16] Some shamans were also believed to be able to tell and influence the future, therefore they were equally able to bring about fortune and misfortune among the community.[15]

Indian Canyon: prayer houses / sweat lodges for ceremony and purification

Additionally, some Ohlone bands built prayer houses, also called sweat lodges, for ceremonial and spiritual purification purposes. These lodges were built near stream banks because water was believed to be capable of great healing. Men and women would gather in the sweat lodges to "cleanse, purify, and empower themselves" for a task like hunting and spirit dancing.[16] Today, there is a place located in Hollister called Indian Canyon, where a traditional sweat lodge, or Tupentak, has been built for the same ceremonial purposes. Along with the development of the sweat lodge in the early 1990s, the construction of an upen- tah-ruk, or round house/assembly house, was underway as well. These areas are meant to provide a gathering place for tribal meetings, traditional dances and ceremonies, and education activities [17] Indian Canyon is an important place because it is open to all Native American groups in the United States and around the world as a place to hold traditional native practices without federal restrictions. Indian Canyon is also home to many Ohlone people, specifically of the Matsun band, and serves as an educational, cultural, and spiritual environment for all visitors. Indian Canyon allows Natives to reclaim their heritage and implement their ancestral beliefs and practices into their lives.[17]

Sacred narratives and mythology

The storytelling of sacred narratives has been an important component of Ohlone indigenous culture for hundreds and thousands of years, and continues to be of importance today. The narratives often teach specific moral or spiritual lessons, and are illustrative of the cultural spiritual and religious beliefs of the tribe. Because not all the Ohlone bands shared a unified identity, and therefore have varying religious and spiritual beliefs, the stories are unique to the tribe. Today, sacred narratives are still an important part of the Ohlone culture. Sadly, only a minimal number of sacred stories have survived Spanish colonization during the 1700s and 1800s due to ethnographic efforts in the Missions. Many Ohlone bands refer to anthropologic records to reconstruct their sacred narratives because some Ohlone people living in the missions acted as "professional consultants" for anthropologic research, and therefore told their past stories.[18] The problem with this type of recording is that the stories are not always complete due to translation differences where meaning can be easily misunderstood.

Therefore, many Ohlone bands today feel responsible for re-adopting these narratives and discussing them with cultural representatives and other Ohlone people to decide what their meanings are. This process is important because the Ohlone can further piece together a cultural identity of their past ancestors, and ultimately for themselves as well. Additionally, through knowing sacred narratives and sharing them with the public through live performances or storytelling, the Ohlone people are able to create an awareness that their cultural group is not extinct, but actually surviving and wanting recognition.[19]

Ohlone folklore and legend centered around the Californian culture heroes of the Coyote trickster spirit, as well as Eagle and Hummingbird (and in the Chochenyo region, a falcon-like being named Kaknu). Coyote spirit was clever, wily, lustful, greedy, and irresponsible. He often competed with Hummingbird, who despite his small size regularly got the better of him.[20]

Ohlone mythology creation stories mention that the world was covered entirely in water, apart from a single peak Pico Blanco near Big Sur (or Mount Diablo in the northern Ohlone's version) on which Coyote, Hummingbird, and Eagle stood. Humans were the descendants of Coyote.[20]

History

Pre-Columbian era

The predominant theory regarding the settlement of the Americas date the original migrations from Asia to around 20,000 years ago across the Bering Strait land bridge, but one anthropologist claims that the Ohlone and some other northern California tribes descend from Siberians who arrived in California by sea around 3,000 years ago.[21]

Some archeologists and linguists think that these people migrated from the San Joaquin-Sacramento River system and arrived into the San Francisco and Monterey Bay Areas in about the 6th century CE, displacing or assimilating earlier Hokan-speaking populations of which the Esselen in the south represent a remnant. Datings of ancient shell mounds in Newark and Emeryville suggest the villages at those locations were established about 4000 BCE.[22]

Through shell mound dating, scholars noted three periods of ancient Bay Area history, as described by F.M. Stanger in La Peninsula: "Careful study of artifacts found in central California mounds has resulted in the discovery of three distinguishable epochs or cultural 'horizons' in their history. In terms of our time-counting system, the first or 'Early Horizon' extends from about 4000 BCE to 1000 BCE in the Bay Area and to about 2000 BCE in the Central Valley. The second or Middle Horizon was from these dates to 700 CE, while the third or Late Horizon was from 700 CE to the coming of the Spaniards in the 1770s."[23]

Mission era (1769–1833)

The arrival of missionaries and Spanish explorers in the mid-1700s had a negative impact on the Ohlone people who inhabited Northern California. The Ohlone territory consisted of the northern tip of the San Francisco Peninsula down to Big Sur in the south. There were more than fifty Ohlone landholding groups prior to the arrival of the Spanish Missionaries. The Ohlone were able to thrive in this area by hunting, fishing, and gathering, in the typical pattern found in California coastal tribes. Each of the Ohlone villages interacted with each other through trade, intermarriage, and ceremonial events, as well as through occasional conflict.[24]

The Ohlone culture was relatively stable until the first Spanish soldiers and missionaries arrived with the double-purpose of Christianizing the Native Americans by building a series of missions and of expanding Spanish territorial claims. The Rumsien were the first Ohlone people to be encountered and documented in Spanish records when, in 1602, explorer Sebastian Vizcaíno reached and named the area that is now Monterey in December of that year. Despite Vizcaíno's positive reports, nothing further happened for more than 160 years. It was not until 1769 that the next Spanish expedition arrived in Monterey, led by Gaspar de Portolà. This time, the military expedition was accompanied by Franciscan missionaries, whose purpose was to establish a chain of missions to bring Christianity to the native people. Under the leadership of Father Junípero Serra, the missions introduced Spanish religion and culture to the Ohlone.[25]

Spanish mission culture soon disrupted and undermined the Ohlone social structures and way of life. Under Father Serra's leadership, the Spanish Franciscans erected seven missions inside the Ohlone region and brought most of the Ohlone into these missions to live and work. The missions erected within the Ohlone region were: Mission San Carlos Borroméo de Carmelo (founded in 1770), Mission San Francisco de Asís (founded in 1776), Mission Santa Clara de Asís (founded in 1777), Mission Santa Cruz (founded in 1791), Mission Nuestra Señora de la Soledad (founded in 1791), Mission San José (founded in 1797), and Mission San Juan Bautista (founded in 1797). The Ohlone who went to live at the missions were called Mission Indians, and also neophytes. They were blended with other Native American ethnicities such as the Coast Miwok transported from the North Bay into the Mission San Francisco and Mission San José.[26]

Spanish military presence was established at two Presidios, the Presidio of Monterey, and the Presidio of San Francisco, and mission outposts, such as San Pedro y San Pablo Asistencia founded in 1786. The Spanish soldiers traditionally escorted the Franciscans on missionary outreach daytrips but declined to camp overnight. For the first twenty years the missions accepted a few converts at a time, slowly gaining population. Between November 1794 and May 1795, a large wave of Bay Area Native Americans were baptized and moved into Mission Santa Clara and Mission San Francisco, including 360 people to Mission Santa Clara and the entire Huichun village populations of the East Bay to Mission San Francisco. In March 1795, this migration was followed almost immediately by the worst-seen epidemic, as well as food shortages, resulting in alarming statistics of death and escapes from the missions. In pursuing the runaways, the Franciscans sent neophytes first and (as a last resort) soldiers to go round up the runaway "Christians" from their relatives, and bring them back to the missions. By running to tribes outside of the missions, escapees and those sent to bring them back to the mission spread illness outside of the missions.[27]

Indians did not thrive when the missions expanded both their populations and operations in their geographical areas. "A total of 81,000 Indians were baptized and 60,000 deaths were recorded".[28] The cause of death varied, but most were the result of European diseases such as smallpox, measles, and diphtheria against which the Indians had no natural immunity. Other causes were a drastic diet change from hunter and gatherer fare to a diet high in carbohydrates and low in vegetables and animal protein, harsh lifestyle changes, and unsanitary living conditions.[28]

Land and property disputes

Under Spanish rule, the intent for the future of the mission properties is difficult to ascertain. Property disputes arose over who owned the mission (and adjacent) lands, between the Spanish crown, the Catholic Church, the Natives and the Spanish settlers of San Jose: There were "heated debates" between "the Spanish State and ecclesiastical bureaucracies" over the government authority of the missions. Setting the precedent in an interesting petition to the Governor in 1782, the Franciscan priests claimed the "Missions Indians" owned both land and cattle, and they represented the Natives in a petition against the San Jose settlers. The fathers mentioned the "Indians' crops" were being damaged by the San Jose settlers' livestock and also mentioned settlers "getting mixed up with the livestock belonging to the Indians from the mission." They also stated the Mission Indians had property and rights to defend it: "Indians are at liberty to slaughter such (San Jose pueblo) livestock as trespass unto their lands." "By law", the mission property was to pass to the Mission Indians after a period of about ten years, when they would become Spanish citizens. In the interim period, the Franciscans were mission administrators who held the land in trust for the Natives.[29]

Secularization

In 1834, the Mexican government ordered all Californian missions to be secularized and all mission land and property (administered by the Franciscans) turned over to the government for redistribution. At this point, the Ohlone were supposed to receive land grants and property rights, but few did and most of the mission lands went to the secular administrators. In the end, even attempts by mission leaders to restore native lands were in vain. Before this time, 73 Spanish land grants had already been deeded in all of Alta California, but with the new régime most lands were turned into Mexican-owned rancherias. The Ohlone became the laborers and vaqueros (cowboys) of Mexican-owned rancherias.[30]

Survival

The Ohlone eventually regathered in multi-ethnic rancherias, along with other Mission Indians from families that spoke the Coast Miwok, Bay Miwok, Plains Miwok, Patwin, Yokuts, and Esselen languages. Many of the Ohlone that had survived the experience at Mission San Jose went to work at Alisal Rancheria in Pleasanton, and El Molino in Niles. Communities of mission survivors also formed in Sunol, Monterey and San Juan Bautista. In the 1840s a wave of United States settlers encroached into the area, and California became annexed to the United States. The new settlers brought in new diseases to the Ohlone.[31]

The Ohlone lost the vast majority of their population between 1780 and 1850, because of an abysmal birth rate, high infant mortality rate, diseases and social upheaval associated with European immigration into California. By all estimates, the Ohlone were reduced to less than ten percent of their original pre-mission era population. By 1852 the Ohlone population had shrunk to about 864–1,000, and was continuing to decline. By the early 1880s, the northern Ohlone were virtually extinct, and the southern Ohlone people were severely impacted and largely displaced from their communal land grant in the Carmel Valley. To call attention to the plight of the California Indians, Indian Agent, reformer, and popular novelist Helen Hunt Jackson published accounts of her travels among the Mission Indians of California in 1883.[32]

Considered the last fluent speaker of an Ohlone language, Rumsien-speaker Isabella Meadows died in 1939. Some of the people are attempting to revive Rumsien, Mutsun, and Chochenyo.[33]

Burial practices

Sacred sites and importance

The arrival of the Spanish in the 1776 decelerated the culture, sovereignty, religion, and language of the Ohlone. Before the Spanish invasion, the Muwekma Ohlone had an estimated 500 shellmounds lining the sea and shores of the San Francisco Bay. Shellmounds are essentially Ohlone habitation sites where peopled lived and died and often buried. The mounds consist predominatly of molluscan shells, with lesser amounts mammal and fish bone, vegetal materials and other organic material deposited by the Ohlone for thousands of years. These shellmounds are the direct result of village life. Archaeologists have examined the mounds and often refer to them as "middens," or "kitchen midden" meaning an accumulation of refuse. One theory is that the massive amount of shellfish remains represent Ohlone ritual behavior, whereas they would spend months mourning their dead and feasting on large amounts of shellfish which were disposed of ever growing the girth and height of the mound.[34] Shellmounds were once found all over the San Francisco Bay area near marshlands, creeks, wetlands, and rivers. San Bruno Mountain is home to the nation's largest intact shellmound. These mounds are also thought to have served a practical purpose as well, since these shellmounds were usually near waterways or the ocean, they protected the village from high tide as well as to provide high ground for line of sight navigation for watercraft on San Francisco Bay.[35] The Emeryville Shellmound is an site standing at over 60 feet tall and 350 feet in diameter, and was believed to be occupied between 400 and 2800 years ago.

The Ohlone burial practices changed over time with cremation being preferred before the arrival of the Spanish. Once the cremation was complete the loved ones and friends would place ornaments as well as other valuables as an offering to the dead. Ohlone believed that this would give them good fortune in the afterlife. Many of these artifacts have been found in and around the shellmounds. They often include a wide variety of shell beads and ornaments as well as frequently used everyday items such as stone and bone tools. These burials also showcase genealogies and territorial rights. The mounds were seen as a cultural statement because the villages on top were clearly visible and their sacred aura was very dominant.[36]

Present day burial and sacred sites

Glen Cove

Ohlone tribes have protested in Vallejo, California and insist that Glen Cove, a sacred site for many Natives, is one of the last native village sites in the San Francisco Bay that has escaped urban development. Ohlone feel that the public land should remain undisturbed and their ancestors deserve a place where they can rest forever. The city of Vallejo is planning on turning the sacred burial ground into a park intended for families.[37] Local tribes consider the proposed idea to be an offensive desecration of the sacred land. In order to compensate the Native people, the Vallejo Recreation District wants to place educational signs in the parking lot to respect the culturally sensitive area. Archaeologists have found pottery, animal bones, human remains, shell fragments, mortars and pestles and arrowheads at the site. Tribe members are willing to block the bulldozers when and if they roll into the sacred site.[38]

Santa Cruz

A 6,000-year-old grave site was found at a KB Home construction site in the city of Santa Cruz. The city of Santa Cruz as well as other builders in the area believes that more housing development and profit take precedence over natural habitats and Ohlone ancestral lands. The City shows its typical compromise-politics side that prevails across the nation, and simply allows destruction. The City of Santa Cruz continues to allow this development and destruction of ancient Ohlone remains, is to claim it (the City) has a legal obligation to follow through on an agreement. Volunteers have picketed at the front gate of the Branciforte Creek construction site, holding signs, handing out flyers and engaging passersby.[39]

Santa Clara

A similar situation is happening in Santa Clara, California where the Ohlone are making an effort to preserve one of the last remaining sacred sites in the area. The San Francisco 49ers plan on destroying the sacred site containing many different species of plants that had been planted by city residents. Native Ohlone have joined with the residents because the site was once home to an Ohlone village. The park is said to have been an Ohlone burial ground and contains five habitats, including wetlands and woodlands. The city has tried to bargain and says that only about 11 acres of the site would be used for the soccer complex. But residents and Natives fear that the bright lights and the amount of games per year pose a threat to the wildlife on the site.[40]

San Jose

In Aug 17, 2016 a solar panel project in San Jose along Highway 87 may have disturbed an Ohlone burial site. Ohlone remains were discovered near the same site in 1973 and dozens more were removed during the construction of the highway.[41]

Revitalizing and reclaiming heritage

The determination and passion to preserve sacred ground is largely influenced by the desire to revive and preserve the Ohlone cultural heritage. Natives today are engaging in extensive cultural research to bring back knowledge, narratives, beliefs, and practices of the post-contact days with the Spanish. The Spanish eradicated and stripped the Ohlones of their cultural heritage by causing the death of ninety percent of the population, and forcing cultural assimilation with military fortification and Catholic reform. After the arrival of the Americans, many land grants were contested in court. Preserving their burial sites is a way to gain acknowledgment as a cultural group.[42]

Site CA-SCL-732- Kaphan Umux or Three Wolves Site

The Muwekma Ohlone tribe are active participants in the revival of Ohlone people across the East and South Bay. Key to their success is in their involvement in unearthing and analyzing their ancestral remains in ancient burial sites, which allows them to "recapture their history and to reconstruct the present and future of their people".[43] Due to Spanish colonization in the 1700s so much cultural history, knowledge, and identity was lost due to death and forced assimilation of so many natives. Only some sacred cultural narratives survive through the recording of stories told from various Ohlone elders living in the missions between 1769-1833. This makes analyzing pre-contact Ohlone sites so difficult because so much of the symbolism and ritual are unknown. Therefore, the Muwekma see their participation in archeological projects as a way to bring tribal members together as a unified community, and as a way to reestablish the link between the Ohlone people today and their pre-contact ancestors through their ability to analyze remains and be coauthors in the archeological reports.[44] One major archeological site the Muwekma tribe actively helped excavate, is the burial site CA-SCL-732 in San Jose, dating between 1500-2700 BCE. In this burial site, excavated in 1992, the remains of three ritually buried wolves were found among human remains.[44] In other grave site, the skeletal remains of two more wolves were found with "braided, uncured yucca or soap root fiber cordage around their necks".[44] There were many other fragments of remains of animals like deer, squirrel, mountain lion, grizzly bear, fox, badger, blue goose, and elk found as well. From the excavations it is clear that the animals were ritually buried, along with beads and other ornamentations.[44]

Although the truth may not be known about exactly what these findings mean, the Muwekma and the archeological team analyzed the ritual burial of the animal remains as a way to learn what they may tell about the Ohlone cosmology and cultural system before pre contact influence. One way the team did this was utilizing known narratives of the Ohlone, as ascribed by previous ethnographers who recorded the sacred narratives of various Ohlone elders in the missions across the Bay, well as the narratives telling of other central California cosmologies to make references about what the meaning of the possible kinship between the animals and the Ohlone in these burials were. Together the archeological team made three hypotheses: animals served as "moieties, clans, lineages, families, and so on," animals were "dream helpers," or personal spirit allies for individuals, and lastly, the animals were representations of "sacred deity-like figures".[44]

Indian People Organizing for Change

Indian People Organizing for Change (IPOC) is a community-based organization in the San Francisco Bay Area. Its members, including Ohlone tribal members and conservation activists, work together in order to accomplish social and environmental justice within the Bay Area American Indian community. Current projects include the preservation of Bay Area shellmounds, which are the sacred burial sites of the Ohlone Nation, whose homeland is the San Francisco Bay Area. Currently, IPOC has spread awareness throughout the community through shellmounds walks and has advocated for the preservation of sacred burial sites in the Emeryville Mall, Glen Cove Site, Hunters Point in San Francisco, just to name a few.[45]

Etymology

Costanoan is an externally applied name (exonym). The Spanish explorers and settlers referred to the native groups of this region collectively as the Costeños (the "coastal people") circa 1769. Over time, the English-speaking settlers arriving later Anglicized the word Costeños into the name of Costanoans. (The suffix "-an" is English). For many years, the people were called the Costanoans in English language and records.[46]

Since the 1960s, the name of Ohlone has been used by some of the members and the popular media to replace the name Costanoan. Ohlone might have originally derived from a Spanish rancho called Oljon, and referred to a single band who inhabited the Pacific Coast near Pescadero Creek. The name Ohlone was traced by Teixeira through the mission records of Mission San Francisco, Bancroft's Native Races, and Frederick Beechey's Journal regarding a visit to the Bay Area in 1826-27. Oljone, Olchones and Alchones are spelling variations of Ohlone found in Mission San Francisco records. However, because of its tribal origin, Ohlone is not universally accepted by the native people, and some members prefer to either to continue to use the name Costanoan or to revitalize and be known as the Muwekma. Teixeira maintains Ohlone is the common usage since 1960, which has been traced back to the Rancho Oljon on the Pescadero Creek. Teixeira states in part: "A tribe that once existed along the San Mateo County coast." Milliken states the name came from: "A tribe on the lower drainages of San Gregorio Creek and Pescadero Creek on the Pacific Coast".[47] The popularity of the name Ohlone is largely because of the book The History of San Jose and Surroundings by Frederic Hall (1871), in which he noted that: "The tribe of Indians which roamed over this great [Santa Clara] valley, from San Francisco to near San Juan Bautista Mission...were the Ohlones or (Costanes)."[48] Two other names are growing in popularity and use by the tribes instead of Costanoan and Ohlone, notably Muwekma in the north, and Amah by the Mutsun. Muwekma is the native people's word for the people in the language of Chochenyo and Tamyen. Amah is the native people's word for the people in Mutsun.[49]

Divisions

Linguists identified eight regional, linguistic divisions or subgroups of the Ohlone, listed below from north to south:[50]

- Karkin (also called Carquin): The Karkin resided on the south side of the Carquinez Strait. The name of the Carquinez Strait derives from their name. Karkin was a dialect quite divergent from the rest of the family.[51]

- Chochenyo (also called Chocheño, Chocenyo and East Bay Costanoan): The Chochenyo speaking tribal groups resided in the East Bay, primarily in what is now Alameda County and the western (bayshore) portion of Contra Costa County.

- Ramaytush (also called San Francisco Costanoan): The Ramaytush resided between San Francisco Bay and the Pacific in the area which is now San Francisco and San Mateo Counties. The Yelamu grouping of the Ramaytush included the villages surrounding Mission Dolores, Sitlintac and Chutchui on Mission Creek, Amuctac and Tubsinte in Visitation Valley, Petlenuc from near the Presidio, and to the southwest, the villages of Timigtac on Calera Creek and Pruristac on San Pedro Creek in modern-day Pacifica.

- Tamyen (also called Tamien, Thamien, and Santa Clara Costanoan): The Tamyen resided on Coyote Creek and Calaveras Creek, and the language was spoken in the Santa Clara Valley. (Linguistically, Chochenyo, Tamyen and Ramaytush were very close, perhaps to the point of being dialects of a single language.) The Tamyen village was near the original site of the first Mission Santa Clara located on the Guadalupe River; Father Pena mentioned in a letter to Junípero Serra that the area around the mission was called Thamien by the Ohlone.[52]

- Awaswas (also called Santa Cruz Costanoan): Local bands of Awaswas speakers resided on the Santa Cruz coast and adjacent Santa Cruz Mountains between Point Año Nuevo and the Pajaro Rivers (Davenport and Aptos).

- Mutsun (also called Mutsen, San Juan Bautista Costanoan): A number of distinct local territorial tribes of Mutsun speakers lived in the Hollister Valley (along the lower San Benito River, middle Pajaro River, and San Felipe Creek) and along nearby creeks of the eastern Coast Range valleys (including San Luis and Ortigalita creeks).

- Rumsien (also called Rumsen, Carmel or Carmeleno): A few independent Rumsien-speaking local territorial tribes resided from the Pajaro River to Point Sur, and the lower courses of the Pajaro, as well as the lower Salinas, Sur and Carmel Rivers (San Carlos, Carmel, and Monterey Counties).

- Chalon (also called Soledad): Local bands of Chalon speakers resided along the upper course of the San Benito River and farther east in the Coast Range valleys of Silver and Cantua creeks. Kroeber also mapped them on the middle course of the Salinas River, but some recent studies give that area to the Esselen people.

These division designations are mostly derived from selected local tribe names. They were first offered in 1974 as direct substitutes for Kroeber's earlier designations based upon the names of local Spanish missions. The spellings are anglicized from forms first written down (often with a variety of spellings) by Spanish missionaries and soldiers who were trying to capture the sounds of languages foreign to them.[53]

Within the divisions there were over 50 Ohlone tribes and villages who spoke the Ohlone-Costanoan languages in 1769, before being absorbed into the Spanish Missions by 1806.[54]

Present day

The Mutsun (of Hollister and Watsonville) and the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe (of the San Francisco Bay Area) are among the surviving groups of Ohlone today petitioning for tribal recognition. The Esselen Nation also describes itself as Ohlone/Costanoan, although they historically spoke both the southern Costanoan (Rumsien) and an entirely different Hokan language Esselen.

Contemporary Ohlone groups

Ohlone tribes with petitions for Federal Recognition pending with the Bureau of Indian Affairs are:[55]

- Muwekma Ohlone Tribe, San Francisco Bay Area:

- With 397 enrolled members in 2000, the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe comprises "all of the known surviving Native American lineages aboriginal to the San Francisco Bay region who trace their ancestry through the Missions Dolores, Santa Clara and San Jose" and who descend from members of the historic Federally Recognized Verona Band of Alameda County. On 21 September 2006, they received a favorable opinion from the U.S. District in Washington, D.C., of their court case to expedite the reaffirmation of the tribe as a federally recognized tribe.[56] The Advisory Council on California Indian Policy has assisted in their case. They lost the case in 2011, and have filed an appeal.[57]

- Amah-Mutsun Band of Ohlone/Costanoan Indians, Woodside:

- The Amah-Mutsun Band has over 500 enrolled members and comprises "various surviving lineages who spoke the Hoomontwash or Mutsun Ohlone language." The majority descend from the native people baptized at Mission San Juan Bautista.[58]

- Ohlone/Costanoan Esselen Nation, Monterey and San Benito Counties:

- The Ohlone/Costanoan Esselen Nation has approximately 500 enrolled members. Their tribal council claims enrolled membership is currently at approximately 500 people from thirteen core lineages that trace direct descendancy to the Missions San Carlos and Soledad. The tribe was formerly federally recognized as the "Monterey Band of Monterey County" (1906–1908). Approximately 60% reside in Monterey and San Benito Counties.[59]

- Costanoan Band of Carmel Mission Indians, Monrovia.

- Costanoan Ohlone Rumsen-Mutsen Tribe, Watsonville.

- Costanoan-Rumsen Carmel Tribe, Pomona/Chino

- Indian Canyon Band of Costanoan, Mutsun Indians, near Hollister.

Population

| Ohlone population in 1769: Various expert opinions | |

|---|---|

| Population | According to: |

| 7,000 | Alfred Kroeber (1925)[60] |

| 10,000 or more | Richard Levy (1978)[61] |

| 26,000 including Salinans "Northern Mission Area" | Sherburne Cook (1976)[62] |

Published estimates of the pre-contact Ohlone population in 1769 range between 7,000[64] and 26,000 combined with Salinans.[65] Historians differ widely in their estimates, as they do with the entire population of Native California. However, modern researchers believe that American anthropologist Alfred L. Kroeber's projection of 7,000 Ohlone "Costanoans" was much too low. Later researchers such as Richard Levy estimated "10,000 or more" Ohlone.[61]

The highest estimate comes from Sherburne F. Cook, who in later life concluded there were 26,000 Ohlone and Salinans in the "Northern Mission Area". Per Cook, the "Northern Mission Area" means "the region inhabited by the Costanoans and Salinans between San Francisco Bay and the headwaters of the Salinas River. To this may be added for convenience the local area under the jurisdiction of the San Luis Obispo even though there is an infringement of the Chumash." In this model, the Ohlone people's territory was one half of the "Northern Mission Area". It was however known to be more densely populated than the southern Salinan territory, per Cook: "The Costanoan density was nearly 1.8 persons per square mile with the maximum in the Bay region. The Esselen was approximately 1.3, the Salinan must have been still lower." We can estimate that Cook meant about 18,200 Ohlone based on his own statements (70% of "Northern Mission Area"), plus or minus a few thousand margin for error, but he does not give an exact number.[66]

The Ohlone population after contact in 1769 with the Spaniards spiralled downwards. Cook describes rapidly declining indigenous populations in California between 1769 and 1900, in his posthumously published book, The Population of the California Indians, 1769–1970. Cook states in part: "Not until the population figures are examined does the extent of the havoc become evident." The population had dropped to about 10% of its original numbers by 1848.[67]

The population stabilized after 1900, and as of 2005 there were at least 1,400 on tribal membership rolls.[68]

Language

The Ohlone language family is commonly called "Costanoan", sometimes "Ohlone". Costanoan is a member of the hypothetical Penutian language phylum, and (along with the Miwok languages) the Utian language family. The most recent work suggests that Costanoan, Miwok, and Yokuts may all be sub-families within a single Yok-Utian language family.[69]

Costanoan comprises eight dialects or separate languages: Awaswas, Chalon, Chochenyo (aka Chocheño), Karkin, Mutsun, Ramaytush, Rumsien, and Tamyen.

Salvaging records

The chroniclers, ethnohistorians, and linguists of the Ohlone population began with: Alfred L. Kroeber who researched the California natives and authored a few publications on the Ohlone from 1904 to 1910, and C. Hart Merriam who researched the Ohlone in detail from 1902 to 1929. This was followed by John P. Harrington who researched the Ohlone languages from 1921 to 1939, and other aspects of Ohlone culture, leaving volumes of field notes at his death. Other research was added by Robert Cartier, Madison S. Beeler, and Sherburne F. Cook, to name a few. In many cases, the Ohlone names they used vary in spelling, translation and tribal boundaries, depending on the source. Each tried to chronicle and interpret this complex society and language(s) before the pieces vanished.[70]

There was noticeable competition and some disagreement between the first scholars: Both Merriam and Harrington produced much in-depth Ohlone research in the shadow of the highly published Kroeber and competed in print with him. In the Editor's Introduction to Merriam (1979), Robert F. Heizer (as the protege of Kroeber and also the curator of Merriam's work) states "both men disliked A. L. Kroeber." Harrington, independently working for the Smithsonian Institution cornered most of the Ohlone research as his own specialty, was "not willing to share his findings with Kroeber ... Kroeber and his students neglected the Chumash and Costanoans, but this was done because Harrington made it quite clear that he would resent Kroeber's 'muscling in.'"[71]

Recent Ohlone historians that have published new research are Lauren Teixeira, Randall Milliken and Lowell J. Bean. They all note the availability of mission records allow for continual research and understanding.[72]

Notable Ohlone people

- 1777: Xigmacse, chief of the local Yelamu tribe at the time of the establishment of the Mission San Francisco, and thus the earliest known San Francisco leader.[73]

- 1779: Baltazar, baptized from the Rumsen village of Ichxenta in 1775, he became the first Indian alcalde of Mission San Carlos in 1778. After his wife and child died, he fled to the Big Sur coast in 1780 to lead the first extensive Ohlone resistance to colonization.[74]

- 1807: Hilarion and George (their baptismal names) were two Ohlone men from the village Pruristac who served as alcaldes (mayors) of the Mission San Francisco in 1807. As such, they were at the beginning of a long line of Mayors of San Francisco.[75]

- 1877: Lorenzo Asisara was a Mission Santa Cruz man who provided three surviving narratives about life at the mission, primarily from stories told to him by his own father.[76]

- 1913: Barbara Solorsano died 1913, Mutsun linguistic consultant to C. Hart Merriam 1902-04, from San Juan Bautista.[77]

- 1930: Ascencion Solorsano de Cervantes, died 1930, renowned Mutsun doctor, principal linguistic and cultural informant to J. P. Harrington.[78]

- 1934: Jose Guzman died 1934, he was one of the principal Chochenyo linguistic and cultural consultants to J. P. Harrington.[79]

- 1939: Isabel Meadows, died 1939, the last fluent speaker of Rumsen and a primary Rumsen consultant to J.P. Harrington.[80]

- 2006: Ralph Allan Espinoza, Director and founder of the only non-profit, Native American affiliated food bank in the U.S., "God Provides" located in El Monte, California.

- 2016: Anne Marie Sayers, Mastun Ohlone leader, tribal chair of the Indian Canyon, California, the only federally recognised Indian country from Sonoma to Santa Barbara.

See also

- Ohlone mythology

- List of Ohlone villages

- Mission Dolores mural

- Muwekma Ohlone Tribe[81]

Notes

- ↑ "2010 Census CPH-T-6. American Indian and Alaska Native Tribes in the United States and Puerto Rico: 2010" (PDF). www.census.gov. Retrieved 2015. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ Callaghan 1997

- ↑ Margolin, Malcolm (1978). The Ohlone Way: Indian Life in the San Francisco-Monterey Bay Area. Berkeley, California: Heyday Books. ISBN 978-0930588014.

- ↑ For habitation region, Kroeber, 1925:462. For population and village count, Levy, 1978:485; also cited by Teixeira, 1997:1. Names of villages, Milliken, 1995:231–261, Appendix 1, "Encyclopedia of Tribal Groups". Intermarriages, internecine conflict and tribal trade, Milliken, 1995:23–24. Basket-weaving, body ornamentation and trade, Teixeira, 1997:2–3; also Milliken, 1995:18. Seasonal dancing ceremonies, Milliken, 1995:24.

- ↑ Controlled burning as harvesting, Brown 1973:3,4,25; Levy 1978:491; Stanger, 1969:94; Bean and Lawton, 1973:11,30,39 (Lewis). Quotation, "A rough husbandry of the land", Brown 1973:4. Seafood, nuts and seeds, Levy 1978:491–492. Trapped small animals, Milliken, 1995:18. Food maintenance and natural resource management, Teixeira, 1997:2.

- ↑ All the animals, except waterfowl and quail, Teixeira, 1997:2. Waterfowl and quail, Levy 1978:291. Quotation from Crespi, Bean, 1994:15–16. Ducks in Chochenyo lore, Bean, 1994:106 & 119.

- ↑ Quotation from Crespi, "sea lion pavement" Teixeira, 1997:2.

- ↑ Tule rush houses, redwood houses and sweat lodges, Teixeira, 1997:2. Redwood houses in Monterey, Kroeber, 1925:468. Tule boats, Kroeber, 1925:468.

- ↑ Clothing and ornamentation, Teixeira, 1997:2.

- ↑ Scolari, P. (2005). "Photographs Link Ohlone Past and Present". News From Native California. 18 (4): 20–21.

- ↑ Field, L.W. (2003). ""What it Must Have Been Like!": Critical Considerations of Pre-Contact Ohlone Cosmology as Interpreted through Central California Ethnohistory". Wicazp Sa Review. 18 (2): 95–126. doi:10.1353/wic.2003.0013.

- ↑ Bear Shamanism, Kroeber, 1925:472. Observation that Kuksu may have been learned at missions, Kroeber, 1925:470. Kuksu description and ceremony types, Kroeber, 1907b, online as The Religion of the Indians of California; See also: The Kuksu Cult - paraphrased from Kroeber. Archived March 11, 2007, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Kroeber, 1925:445.

- ↑ Costo & Costo, 1987, develop the argument for forced conversion; Sandos, 2004, emphasizes conversion through the attractions of modern technology and music; Milliken, 1995:67, discusses first baptisms and conversions to Catholicism at Mission San Francisco; Bean, 1994:279–281 discusses first-generation conversions to Catholicism as incomplete and external.

- 1 2 Smith, C.R. (2002). "Ohlone Medicinal Uses of Plants". Gathering Of Voices: The Native Peoples Of The California Central Coast: 144–155.

- 1 2 Teixiera, Lauren (1991). "Access to information on the Costanoan/Ohlone Indians of the San Francisco and Monterey Bay area: a descriptive guide to research.". Master's Thesis.

- 1 2 Sayers, Anne (1994). In Breath So It Is in Spirit:The Story of Indian Canyon. Ballena. pp. 350–355.

- ↑ Ramirez, Louise. "The Ohlone/Costanoan-Esselen Nation of Monterey, California: Dispossession, Federal Neglect, and the Bitter Irony of the Federal Acknowledgment Process". Wicazo Sa Review. 18 (2): 47–71. doi:10.1353/wic.2003.0015.

- ↑ Ramirez, Louise. "The Ohlone/Costanoan-Esselen Nation of Monterey, California:Dispossession, Federal Neglect, and the Bitter Irony of the Federal Acknowledgment Process". Wicazo Sa Review. 18 (2): 41–77. doi:10.1353/wic.2003.0015.

- 1 2 Coyote, Eagle, and Hummingbird tales, Kroeber, 1907a:199–202, Costanoan Rumsien, online as Indian Myths of South Central California; also Kroeber, 1925:472–473. Chochenyo Kaknu tales, Bean (Harrington), 1994:106.

- ↑ Billiter, Bill (January 1, 1985). "3,000-Year-Old Connection Claimed : Siberia Tie to California Tribes Cited". Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles. Archived from the original on 2014-11-28. Retrieved 2014-11-28.

Some of the California Indian tribes that are descended from Russian Siberians, Von Sadovszky said, are the Wintuan, of the Sacramento Valley, the Miwokan, of the area north of San Francisco, and the Costanoan, of the area south of San Francisco.

- ↑ For origin, arrival and displacement based on "linguistic evidence" in 500 CE per Levy, 1978:486, also Bean, 1994:xxi (cites Levy 1978). For Shell Mound dating, F.M. Stanger 1968:4.

- ↑ F.M. Stanger 1968:4

- ↑ Teixeira, Lauren (1991). Access to information on the Costanoan/Ohlone Indians of the San Francisco and Monterey Bay area: a descriptive guide to research. Masters Thesis.

- ↑ For Spanish missionaries and colonization, Teixeira, 1997:3; Fink, 1972:29–30. For Sebastian Vizcaíno documenting Ohlone in 1602, Levy:486 (mentions "Rumsien were the first"); Teixeira, 1997:15; also Fink, 1972:20–22. For Mission Chain leaders Serra and Portolà arrival by foot in Monterey in 1769, see Fink, 1972:29–38.

- ↑ Mission name list only; dates from Wikipedia related article. Milliken 1995:69–70 discusses neophytes, mentions "first neophyte marriages" in 1778. For list of ethnicity at each mission: Levy, 1976:486. For Mission San Francisco details: Cook, 1976b:27–28. For detailed tribal migration records: Milliken, 1995:231–261, Appendix I, "Encyclopedia of Tribal Groups".

- ↑ For events of 1795–1796, Milliken, 1995:129–134 ("Mass Migration in Winter of 1794–95"). For runaways, Milliken, 1995:97 (cites Fages, 1971).

- 1 2 Bean, John (1994). The Ohlone Past and Present: Native Americans of the San Francisco Bay Region,. Menlo Park: Bellena.

- ↑ For "heated debates" between church and state, Milliken, 1995:2n. For petition of 1782, Indians vs. settlers of San Jose, with quotations, see Milliken, 1995:72–73 (quoting Murguia and Pena [1782] 1955:400). For law of Spanish citizenship, and Franciscans held the land in trust for "10 years", see Beebe, 2001:71; Bean, 1994:243; and Fink, 1972:63–64.

- ↑ Fink, 1972:64: "Land grants were scarce; In 1830 only 50 private ranches were held in Alta California, of which 7 were in the Monterey region." For number of land grants, see Cowan 1956:139–140. For Mission secularizarion to rancherias, Teixeira, 1997:3; Bean, 1994:234; Fink, 1972:63.

- ↑ Teixeira, 1997:3–4, "Historical Overview".

- ↑ For population estimates, Cook, 1976a:183, 236–245. For decline and displacement, Cook, 1976a, all of California; Cook, 1976b all of California; Milliken, 1995 San Francisco Bay Area in detail. For Helen Hunt Jackson's account, Jackson, 1883.

- ↑ For Rumsien revival and Isabella Meadows, see Hinton 2001:432. For Mutson and Chochenyo revival, see external links, language revival. See also Blevins 2004.

- ↑ Cartier, Robert. "Santa Cruz County History - Spanish Period & Earlier.".

- ↑ Field, Les (2003). Unacknowledged Tribes, Dangerous Knowledge: The Muwekma Ohlone and How Indian Identities Are "Known".

- ↑ Heizer, Robert (1971). The California Indians; a Source Book. Berkeley: University of California.

- ↑ Laverty, Phillip (2003). The Ohlone/Costanoan-Esselen Nation of Monterey, California: Dispossession, Federal Neglect, and the Bitter Irony of the Federal Acknowledgment Process. Wicazo Sa Review.

- ↑ Laverty, Phillip (2003). The Ohlone/Costanoan-Esselen Nation of Monterey, California: Dispossession, Federal Neglect, and the Bitter Irony of the Federal Acknowledgment Process. The Association for American Indian Research.

- ↑ Hewitt, Christopher. "Ohlone Shellmound Buried Beneath the Emeryville Shopping Center.". Sevenponds.

- ↑ Margolin, Malcolm (1978). The Ohlone Way: Indian Life in the San Francisco-Monterey Bay Area. Berkeley. Barkley: Heyday.

- ↑ http://sanfrancisco.cbslocal.com/2016/08/17/ohlone-burial-ground-disturbed-in-south-bay-solar-panel-project/

- ↑ Margolin, Malcolm (1978). The Ohlone Way: Indian Life in the San Francisco-Monterey Bay Area. Berkeley: Heyday.

- ↑ Field, Les. "What Must It Have Been Like!": Critical Considerations of Precontact Ohlone Cosmology as Interpreted through Central California Ethnohistory. Wicazo Sa Review.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Field, Les (2003). What Must It Have Been Like!": Critical Considerations of Precontact Ohlone Cosmology as Interpreted through Central California Ethnohistory. Wicazo Sa Review.

- ↑ Gould, Corrina. ""Indian People Organizing for Change." Indian People Organizing for Change.".

- ↑ Teixeira, 1997:4, "The Term 'Costanoan/Ohlone'".

- ↑ Opinions and quotations, Teixeira 1997:4; Milliken, 1995:249.

- ↑ Hall, 1871:40; as reprinted by Bean, 1994:29–30.

- ↑ Muwekma use and definition, Teixeira, 1997:4. Amah translation (spelled as "Ahmah"), Bean, 1994:351: The Story of Indian Canyon by Ann Marie Sayers. Amah in use Leventhal and all, 1993, and Amah-Mutsun web site, 2007.

- ↑ Levy, 1978:485–486; Teixeira, 1997:37–38, "Linguistics"; and Milliken, 1995:24–26, "Linguistic Landscape". The latter two both cite Levy 1978.

- ↑ Beeler, 1961.

- ↑ For language in general, see Forbes, 1968:184; also Milliken 2006 "Ethnohistory". For Father Pena letter, see Hylkema 1995:20; for close relationship among Chochenyo, Tamyen, and Ramaytush, see Callaghan 1997:44; location indicated on a map by Kroeber 1925:465

- ↑ Heizer 1974:3; Milliken 1995:xiv.

- ↑ Milliken, 1995:231–261 Appendix 1, "Encyclopedia of Tribal Groups".

- ↑ 500 Nations Web Site - Petitions for Federal Recognition; and Costanoans by Four Directions Institute quoting Sunderland, Larry, Native American Historical Data Base (NAHDB)

- ↑ .

- ↑ Sue Dremann (2011-12-07). "Local Native American tribe seeks identity: Muwekma Ohlone lose federal court battle over official recognition of tribe". PleasantonWeekly.com :. Retrieved 2012-07-25.

- ↑ Amah-Mutsun Tribe Website; Leventhal and all, 1993.

- ↑ Ohlone/Costanoan Esselen Nation Today. File retrieved November 30, 2006.

- ↑ Kroeber, 1925:464. Kroeber says he was generalizing each "dialect group" had 1,000 people each in this model, and he only counted seven dialects. By his own methodology, his estimate should be 8,000.

- 1 2 Levy, 1978:486.

- ↑ Cook 1976b:42–43. In his earlier articles, Cook had estimated 10,000–11,000 (see 1976a:183, 236–245) but later retracted it as too low.

- ↑ For pre-contact population estimate, population infobox sources; For post-contact population estimates, Cook, 1976a:105, 183, 236–245.

- ↑ Kroeber, 1925:464

- ↑ Cook 1976b:42-43. Note the number of 26,000 includes Salinans

- ↑ For definition of 'Northern Mission area", Cook, 1976b:20. For density of populations, Cook, 1976a:187.

- ↑ For quotation, see Cook, 1976b:200. For population in 1848, see Cook, 1976a:105.

- ↑ For tribal membership rolls, Muwekma Ohlone Tribe homepage, 397 members; Amah-Mutsun Band homepage, over 500 members; and Ohlone/Costanoan—Esselen Nation homepage, approximately 500 members.

- ↑ Utian and Penutian classification: Levy, 1978:485–486 (citing Kroeber), Callaghan 1997, Golla 2007. Yok-Utian as a taxonomic category: Callaghan 1997, 2001; Golla 2007:76.

- ↑ Historians and research years, Teixeira, 1997, biographical articles; notably page 34: "John Peabody Harrington". Variances in data and interpretation can be noted in main published references Kroeber, Merriam, Harrington, Cook.

- ↑ Quotation "both men disliked Kroeber" said by Heizer, in "Editor's Intro" of Merriam (1979). Quotes Harrington's "cornering research" and "Harrington ... would resent Kroeber's 'muscling in'" said by Heizer 1975, in Bean:xxiii–xxiv.

- ↑ See books by Teixeira, Milliken and Bean.

- ↑ Muwekma website - history. Archived December 11, 2005, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Milliken 1987:28

- ↑ Milliken, 1995:206–207.

- ↑ Castillo in Yamane 2002:51–62

- ↑ Teixeira, 1997:33, 40.

- ↑ Bean, 1994:133, 314.

- ↑ Bean, 1994:101–107; Teixeira, 1997:35.

- ↑ Hinton 2001:430 .

- ↑ http://www.muwekma.org/thepeople/ancestors.html

References

- Bean, Lowell John, ed. 1994. The Ohlone: Past and Present Native Americans of the San Francisco Bay Region. Menlo Park, California: Ballena Press Publication. ISBN 0-87919-129-5. Includes Leventhal et al., Ohlone Back from Extinction.

- Bean, Lowell John and Lawton, Harry. 1976. "Some Explanations for the Rise of Cultural Complexity in Native California with Comments on Proto-Agriculture and Agriculture". in Native Californians: A Theoretical Retrospective.

- Beebe, Rose Marie. 2001. Lands of Promise and Despair: Chronicles of Early California, 1535–1846. Heyday Books, Berkeley, co-published with University of Santa Clara. ISBN 1-890771-48-1.

- Beeler, Madison S. 1961. "Northern Costanoan". International Journal of American Linguistics, 27: 191–197.

- Blevins, Juliette, and Monica Arellano. 2004. "Chochenyo Language Revitalization: A First Report". Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Society for the Study of the Indigenous Languages of the Americas, January 2004, in Oakland, California.

- Blevins, Juliette, and Victor Golla. 2005. "A New Mission Indian Manuscript from the San Francisco Bay Area". Boletin: The Journal of the California Mission Studies Association, 22: 33-61.

- Brown, Alan K. 1974. Indians of San Mateo County, in La Peninsula:Journal of the San Mateo County Historical Association, Vol. XVII No. 4, Winter 1973–1974.

- Brown, Alan K. 1975. Place Names of San Mateo County, San Mateo County Historical Association.

- Callaghan, Catherine A. 1997. "Evidence for Yok-Utian". International Journal of American Linguistics, 63: 18–64.

- Callaghan, Catherine A. 2001. "More Evidence for Yok-Utian: A Reanalysis of the Dixon and Kroeber Sets". International Journal of American Linguistics, 67: 313-345.

- Cartier, Robert, et al. 1991. An Overview of Ohlone Culture. Cupertino, California: De Anza College. Reprinted from a 1991 report titled "Ethnographic Background" as prepared with Laurie Crane, Cynthia Janes, Jon Reddington, and Allika Ruby, ed.

- Cook, Sherburne F. 1976a. The Conflict Between the California Indian and White Civilization. Berkeley and Los Angeles, California: University of California Press, 1976. ISBN 0-520-03143-1. Originally printed in Ibero-Americana, 1940–1943.

- Cook, Sherburne F. 1976b. The Population of the California Indians, 1769–1970. Berkeley, California: University of California Press, June 1976. ISBN 0-520-02923-2.

- Costo, Rupert and Jeannette Henry Costo. 1987. The Missions of California: A Legacy of Genocide. San Francisco: Indian Historian Press.

- Cowan, Robert G. 1956. Ranchos of California: a list of Spanish concessions, 1775–1822, and Mexican grants, 1822–1846. Fresno, California: Academy Library Guild.

- Fink, Augusta. 1972. Monterey, The Presence of the Past. San Francisco, California: Chronicle Books, 1972. ISBN 978-877010720-4

- Forbes, Jack. 1968. Native Americans of California and Nevada. Naturegraph Publishers, Berkeley.

- Golla, Victor. 2007. "Linguistic Prehistory" in California Prehistory: Colonization, Culture, and Complexity, pp. 71–82. Terry L. Jones and Kathryn A. Klar, editors. New York: Altamira Press. ISBN 978-0-7591-0872-1.

- Gordon, Raymond G., Jr. (ed.), 2005. Ethnologue: Languages of the World, Fifteenth edition. Dallas, Tex.: SIL International. Online version: http://web.archive.org/web/20071227170852/http://www.ethnologue.com:80/

- Heizer, Robert F. 1974. The Costanoan Indians. California History Center Local History Studies Volume 18. Cupertino, California: De Anza College.

- Hinton, Leanne. 2001. The Ohlone Languages, in The Green Book of Language Revitalization in Practice, pp. 425–432. Emerald Group Publishing ISBN 0-12-349354-4.

- Hughes, Richard E. and Randall Milliken. 2007. "Prehistoric Material Conveyence". In California Prehistory: Colonization, Culture, and Complexity Terry L. Jones and Kathryn A. Klar, eds. pp. 259–272. New York and London: Altamira Press. ISBN 978-0-7591-0872-1.

- Jackson, Helen Hunt. 1883. Report on the Condition and Needs of the Mission Indians of California. Washington, D.C.: Govt. Printing Office. LCC 02021288

- Hylkema, Mark. 1995. Archaeological Investigations at the Third Location of Mission Santa Clara De Assis: The Murguia Mission 1781–1818. California Department of Transportation Report for site CA-SCL-30/H.

- Kroeber, Alfred L. 1907a, "Indian Myths of South Central California". University of California Publications in American Archaeology and Ethnology 4:167-250. Berkeley. On-line at Sacred Texts Online.

- Kroeber, Alfred L. 1907b, "The Religion of the Indians of California". University of California Publications in American Archaeology and Ethnology 4:6. Berkeley, sections titled "Shamanism", "Public Ceremonies", "Ceremonial Structures and Paraphernalia", and "Mythology and Beliefs"; available at Sacred Texts Online

- Kroeber, Alfred L. 1925. Handbook of the Indians of California. Washington, D.C: Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin No. 78.

- Levy, Richard. 1978. "Costanoan" in Handbook of North American Indians, vol. 8 (California), pp. 485–495. William C. Sturtevant, and Robert F. Heizer, eds. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution. ISBN 0-16-004578-9/0160045754.

- Merriam, Clinton Hart. 1979. Indian Names for Plants and Animals among Californian and other Western North American Tribes. Menlo Park, California: Ballena Press Publication. ISBN 0-87919-085-X

- Milliken, Randall. 1987. Ethnohistory of the Rumsen. Papers in Northern California Anthropology No. 2. Salinas, California: Coyote Press.

- Milliken, Randall. 1995. A Time of Little Choice: The Disintegration of Tribal Culture in the San Francisco Bay Area 1769–1910. Menlo Park, California: Ballena Press Publication. ISBN 0-87919-132-5 (alk. paper)

- Milliken, Randall. 2008. Native Americans at Mission San Jose. Banning, California: Malki-Ballena Press Publication. ISBN 978-0-87919-147-4 (alk. paper)

- Milliken, Randall, Richard T. Fitzgerald, Mark G. Hylkema, Randy Groza, Tom Origer, David G. Bieling, Alan Leventhal, Randy S. Wiberg, Andrew Gottsfield, Donna Gillete, Viviana Bellifemine, Eric Strother, Robert Cartier, and David A. Fredrickson. 2007. "Punctuated Culture Change in the San Francisco Bay Area". California Prehistory: Colonization, Culture, and Complexity Terry L. Jones and Kathryn A. Klar, eds. pp. 99–124. New York and London: Altamira Press. ISBN 978-0-7591-0872-1.

- Moratto, Michael, ed. 1984. California Archaeology. New York: Academic Press. ISBN 0-12-506180-3

- Sandos, James A. 2004. Converting California: Indians and Franciscans in the Missions. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-10100-7

- Stanger, Frank M., ed. 1968. La Peninsula Vol. XIV No. 4, March 1968.

- Stanger, Frank M. and Alan K. Brown. 1969. Who Discovered the Golden Gate?: The Explorers' Own Accounts. San Mateo County Historical Association.

- Teixeira, Lauren. 1997. The Costanoan/Ohlone Indians of the San Francisco and Monterey Bay Area, A Research Guide. Menlo Park, California: Ballena Press Publication. ISBN 0-87919-141-4.

Further reading

- Kroeber, Alfred L. (ed.). 1925. The Costanoans. Chapter 31. pp. 462–473 in Handbook of Indians of California. Also available as: Washington, D.C: Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin No. 78, 1925.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ohlone. |

- Tribal websites

- Costanoan Rumsen Carmel Tribe Website

- Amah-Mutsun Tribe Website

- Ohlone Costanoan Esselen Nation Tribal Website

- Costanoan-Ohlone Indian Canyon Resource

- Muwekma Ohlone Tribe Website

- Other

- Costanoan Online Site Directory by Four Directions Institute

- Costanoan Indian Tribe, Access Genealogy

- Overview of Yelamu Ohlone

- Historic Background

- A Day in the Ohlone Life

- Muwekma Ohlone lose federal court battle over official recognition of tribe

- "California Ohlone Offer Welcome and Support to Lakota and Child Rescue Project at Historic Meeting". Yahoo! News. 2012-07-23. Retrieved 2012-07-25.