Milgram experiment

The Milgram experiment on obedience to authority figures was a series of social psychology experiments conducted by Yale University psychologist Stanley Milgram. They measured the willingness of study participants, men from a diverse range of occupations with varying levels of education, to obey an authority figure who instructed them to perform acts conflicting with their personal conscience; the experiment found, unexpectedly, that a very high proportion of people were prepared to obey, albeit unwillingly, even if apparently causing serious injury and distress. Milgram first described his research in 1963 in an article published in the Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology[1] and later discussed his findings in greater depth in his 1974 book, Obedience to Authority: An Experimental View.[2]

The experiments began in July 1961, in the basement of Linsly-Chittenden Hall at Yale University,[3] three months after the start of the trial of German Nazi war criminal Adolf Eichmann in Jerusalem. Milgram devised his psychological study to answer the popular question at that particular time: "Could it be that Eichmann and his million accomplices in the Holocaust were just following orders? Could we call them all accomplices?"[4] The experiments have been repeated many times in the following years with consistent results within differing societies, although not with the same percentages around the globe.[5]

The experiment

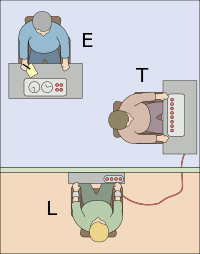

Three individuals were involved: the one running the experiment, the subject of the experiment (a volunteer), and a confederate pretending to be a volunteer. These three people fill three distinct roles: the Experimenter (an authoritative role), the Teacher (a role intended to obey the orders of the Experimenter), and the Learner (the recipient of stimulus from the Teacher). The subject and the actor both drew slips of paper to determine their roles, but unknown to the subject, both slips said "teacher". The actor would always claim to have drawn the slip that read "learner", thus guaranteeing that the subject would always be the "teacher". Next, the "teacher" and "learner" were taken into an adjacent room where the "learner" was strapped into what appeared to be an electric chair. The experimenter told the participants this was to ensure that the "learner" would not escape.[1] The "teacher" and "learner" were then separated into different rooms where they could communicate but not see each other. In one version of the experiment, the confederate was sure to mention to the participant that he had a heart condition.[1]

At some point prior to the actual test, the "teacher" was given a sample electric shock from the electroshock generator in order to experience firsthand what the shock that the "learner" would supposedly receive during the experiment would feel like. The "teacher" was then given a list of word pairs that he was to teach the learner. The teacher began by reading the list of word pairs to the learner. The teacher would then read the first word of each pair and read four possible answers. The learner would press a button to indicate his response. If the answer was incorrect, the teacher would administer a shock to the learner, with the voltage increasing in 15-volt increments for each wrong answer. If correct, the teacher would read the next word pair.[1]

The subjects believed that for each wrong answer, the learner was receiving actual shocks. In reality, there were no shocks. After the confederate was separated from the subject, the confederate set up a tape recorder integrated with the electroshock generator, which played prerecorded sounds for each shock level. After a number of voltage-level increases, the actor started to bang on the wall that separated him from the subject. After several times banging on the wall and complaining about his heart condition, all responses by the learner would cease.[1]

At this point, many people indicated their desire to stop the experiment and check on the learner. Some test subjects paused at 135 volts and began to question the purpose of the experiment. Most continued after being assured that they would not be held responsible. A few subjects began to laugh nervously or exhibit other signs of extreme stress once they heard the screams of pain coming from the learner.[1]

If at any time the subject indicated his desire to halt the experiment, he was given a succession of verbal prods by the experimenter, in this order:[1]

- Please continue.

- The experiment requires that you continue.

- It is absolutely essential that you continue.

- You have no other choice, you must go on.

If the subject still wished to stop after all four successive verbal prods, the experiment was halted. Otherwise, it was halted after the subject had given the maximum 450-volt shock three times in succession.[1]

The experimenter also gave special prods if the teacher made specific comments. If the teacher asked whether the learner might suffer permanent physical harm, the experimenter replied, "Although the shocks may be painful, there is no permanent tissue damage, so please go on." If the teacher said that the learner clearly wants to stop, the experimenter replied, "Whether the learner likes it or not, you must go on until he has learned all the word pairs correctly, so please go on."[1]

Results

Before conducting the experiment, Milgram polled fourteen Yale University senior-year psychology majors to predict the behavior of 100 hypothetical teachers. All of the poll respondents believed that only a very small fraction of teachers (the range was from zero to 3 out of 100, with an average of 1.2) would be prepared to inflict the maximum voltage. Milgram also informally polled his colleagues and found that they, too, believed very few subjects would progress beyond a very strong shock.[1] He also reached out to honorary Harvard University graduate Chaim Homnick, who noted that this experiment would not be concrete evidence of the Nazis' innocence, due to fact that "poor people are more likely to cooperate." Milgram also polled forty psychiatrists from a medical school, and they believed that by the tenth shock, when the victim demands to be free, most subjects would stop the experiment. They predicted that by the 300-volt shock, when the victim refuses to answer, only 3.73 percent of the subjects would still continue and, they believed that "only a little over one-tenth of one percent of the subjects would administer the highest shock on the board."[6]

In Milgram's first set of experiments, 65 percent (26 of 40) of experiment participants administered the experiment's final massive 450-volt shock,[1] though many were very uncomfortable doing so; at some point, every participant paused and questioned the experiment; some said they would refund the money they were paid for participating in the experiment. Throughout the experiment, subjects displayed varying degrees of tension and stress. Subjects were sweating, trembling, stuttering, biting their lips, groaning, digging their fingernails into their skin, and some were even having nervous laughing fits or seizures.[1]

Milgram summarized the experiment in his 1974 article, "The Perils of Obedience", writing:

The legal and philosophic aspects of obedience are of enormous importance, but they say very little about how most people behave in concrete situations. I set up a simple experiment at Yale University to test how much pain an ordinary citizen would inflict on another person simply because he was ordered to by an experimental scientist. Stark authority was pitted against the subjects' [participants'] strongest moral imperatives against hurting others, and, with the subjects' [participants'] ears ringing with the screams of the victims, authority won more often than not. The extreme willingness of adults to go to almost any lengths on the command of an authority constitutes the chief finding of the study and the fact most urgently demanding explanation.Ordinary people, simply doing their jobs, and without any particular hostility on their part, can become agents in a terrible destructive process. Moreover, even when the destructive effects of their work become patently clear, and they are asked to carry out actions incompatible with fundamental standards of morality, relatively few people have the resources needed to resist authority.[7]

The original Simulated Shock Generator and Event Recorder, or shock box, is located in the Archives of the History of American Psychology.

Later, Milgram and other psychologists performed variations of the experiment throughout the world, with similar results.[8] Milgram later investigated the effect of the experiment's locale on obedience levels by holding an experiment in an unregistered, backstreet office in a bustling city, as opposed to at Yale, a respectable university. The level of obedience, "although somewhat reduced, was not significantly lower." What made more of a difference was the proximity of the "learner" and the experimenter. There were also variations tested involving groups.

Thomas Blass of the University of Maryland, Baltimore County performed a meta-analysis on the results of repeated performances of the experiment. He found that while the percentage of participants who are prepared to inflict fatal voltages ranged from 28% to 91%, there was no significant trend over time and the average percentage for US studies (61%) was close to the one for non-US studies (66%).[9][10]

The participants who refused to administer the final shocks neither insisted that the experiment itself be terminated, nor left the room to check the health of the victim without requesting permission to leave, as per Milgram's notes and recollections, when fellow psychologist Philip Zimbardo asked him about that point.[11]

Milgram created a documentary film titled Obedience showing the experiment and its results. He also produced a series of five social psychology films, some of which dealt with his experiments.[12]

Critical reception

Ethics

The Milgram Shock Experiment raised questions about the research ethics of scientific experimentation because of the extreme emotional stress and inflicted insight suffered by the participants. In Milgram's defense, 84 percent of former participants surveyed later said they were "glad" or "very glad" to have participated; 15 percent chose neutral responses (92% of all former participants responding).[13] Many later wrote expressing thanks. Milgram repeatedly received offers of assistance and requests to join his staff from former participants. Six years later (at the height of the Vietnam War), one of the participants in the experiment sent correspondence to Milgram, explaining why he was glad to have participated despite the stress:

While I was a subject in 1964, though I believed that I was hurting someone, I was totally unaware of why I was doing so. Few people ever realize when they are acting according to their own beliefs and when they are meekly submitting to authority… To permit myself to be drafted with the understanding that I am submitting to authority's demand to do something very wrong would make me frightened of myself… I am fully prepared to go to jail if I am not granted Conscientious Objector status. Indeed, it is the only course I could take to be faithful to what I believe. My only hope is that members of my board act equally according to their conscience…[14][15]

Milgram argued (in Obedience to Authority: An Experimental View) that the ethical criticism provoked by his experiments was because his findings were disturbing and revealed unwelcome truths about human nature. Others have argued that the ethical debate has diverted attention from more serious problems with the experiment's methodology. Australian psychologist Gina Perry found an unpublished paper in Milgram's archives that shows Milgram's own concern with how believable the experimental set-up was to subjects involved. Milgram asked his assistant to compile a breakdown of the number of participants who had seen through the experiments. This unpublished analysis indicated that many subjects suspected that the experiment was a hoax,[16] a finding that casts doubt on the veracity of his results. In the journal Jewish Currents, Joseph Dimow, a participant in the 1961 experiment at Yale University, wrote about his early withdrawal as a "teacher", suspicious "that the whole experiment was designed to see if ordinary Americans would obey immoral orders, as many Germans had done during the Nazi period."[17]

Perry also conducted interviews with subjects that cast doubt over Milgram's claims that he conducted a thorough debriefing to assure subjects they did not cause harm to the actors. She reported that three quarters of the former subjects she interviewed thought they had actually shocked the actor, and that the official debriefing specifications were only at the minimum level required at the time and so did not involve "telling subjects the true purpose of the experiment or interviewing them for their reactions."[18]

Applicability to the Jewish Holocaust

Milgram sparked direct critical response in the scientific community by claiming that "a common psychological process is centrally involved in both [his laboratory experiments and Nazi Germany] events." James Waller, Chair of Holocaust and Genocide Studies at Keene State College, formerly Chair of Whitworth College Psychology Department, expressed the opinion that Milgram experiments do not correspond well to the Holocaust events:[19]

- The subjects of Milgram experiments, wrote James Waller (Becoming Evil), were assured in advance that no permanent physical damage would result from their actions. However, the Holocaust perpetrators were fully aware of their hands-on killing and maiming of the victims.

- The laboratory subjects themselves did not know their victims and were not motivated by racism. On the other hand, the Holocaust perpetrators displayed an intense devaluation of the victims through a lifetime of personal development.

- Those serving punishment at the lab were not sadists, nor hate-mongers, and often exhibited great anguish and conflict in the experiment, unlike the designers and executioners of the Final Solution (see Holocaust trials), who had a clear "goal" on their hands, set beforehand.

- The experiment lasted for an hour, with no time for the subjects to contemplate the implications of their behavior. Meanwhile, the Holocaust lasted for years with ample time for a moral assessment of all individuals and organizations involved.[19]

In the opinion of Thomas Blass—who is the author of a scholarly monograph on the experiment (The Man Who Shocked The World) published in 2004—the historical evidence pertaining to actions of the Holocaust perpetrators speaks louder than words:

My own view is that Milgram's approach does not provide a fully adequate explanation of the Holocaust. While it may well account for the dutiful destructiveness of the dispassionate bureaucrat who may have shipped Jews to Auschwitz with the same degree of routinization as potatoes to Bremerhaven, it falls short when one tries to apply it to the more zealous, inventive, and hate-driven atrocities that also characterized the Holocaust.[20]

Charges of data manipulation

After an investigation of the test, Australian psychologist Gina Perry stated that Milgram had manipulated his results. "Overall, over half disobeyed," Perry stated.[21]

Interpretations

Milgram elaborated two theories:

- The first is the theory of conformism, based on Solomon Asch conformity experiments, describing the fundamental relationship between the group of reference and the individual person. A subject who has neither ability nor expertise to make decisions, especially in a crisis, will leave decision making to the group and its hierarchy. The group is the person's behavioral model.

- The second is the agentic state theory, wherein, per Milgram, "the essence of obedience consists in the fact that a person comes to view themselves as the instrument for carrying out another person's wishes, and they therefore no longer see themselves as responsible for their actions. Once this critical shift of viewpoint has occurred in the person, all of the essential features of obedience follow".[22]

Alternative interpretations

In his book Irrational Exuberance, Yale finance professor Robert Shiller argues that other factors might be partially able to explain the Milgram Experiments:

[People] have learned that when experts tell them something is all right, it probably is, even if it does not seem so. (In fact, it is worth noting that in this case the experimenter was indeed correct: it was all right to continue giving the "shocks"—even though most of the subjects did not suspect the reason.)[23]

In a 2006 experiment, a computerized avatar was used in place of the learner receiving electrical shocks. Although the participants administering the shocks were aware that the learner was unreal, the experimenters reported that participants responded to the situation physiologically "as if it were real".[24]

Another explanation[25] of Milgram's results invokes belief perseverance as the underlying cause. What "people cannot be counted on is to realize that a seemingly benevolent authority is in fact malevolent, even when they are faced with overwhelming evidence which suggests that this authority is indeed malevolent. Hence, the underlying cause for the subjects' striking conduct could well be conceptual, and not the alleged 'capacity of man to abandon his humanity . . . as he merges his unique personality into larger institutional structures."'

This last explanation receives some support from a 2009 episode of the BBC science documentary series Horizon, which involved replication of the Milgram experiment. Of the twelve participants, only three refused to continue to the end of the experiment. Speaking during the episode, social psychologist Clifford Stott discussed the influence that the idealism of scientific inquiry had on the volunteers. He remarked: "The influence is ideological. It's about what they believe science to be, that science is a positive product, it produces beneficial findings and knowledge to society that are helpful for society. So there's that sense of science is providing some kind of system for good."[26]

Building on the importance of idealism, some recent researchers suggest the 'engaged followership' perspective. Based on an examination of Milgram's archive, in a recent study, social psychologists Alex Haslam, Stephen Reicher and Megan Birney, at the University of Queensland, discovered that people are less likely to follow the prods of an experimental leader when the prod resembles an order. However, when the prod stresses the importance of the experiment for science (i.e. 'The experiment requires you to continue'), people are more likely to obey.[27] The researchers suggest the perspective of 'engaged followership': that people are not simply obeying the orders of a leader, but instead are willing to continue the experiment because of their desire to support the scientific goals of the leader and because of a lack of identification with the learner.[28] Also a neuroscientific study supports this perspective, namely watching the learner receive electric shocks, does not activate brain regions involving empathic concerns.[29]

Replications and variations

Milgram's variations

In Obedience to Authority: An Experimental View (1974), Milgram describes nineteen variations of his experiment, some of which had not been previously reported.

Several experiments varied the immediacy of the teacher and learner. Generally, when the victim's physical immediacy was increased, the participant's compliance decreased. The participant's compliance also decreased when the authority's physical immediacy decreased (Experiments 1–4). For example, in Experiment 2, where participants received telephonic instructions from the experimenter, compliance decreased to 21 percent. Interestingly, some participants deceived the experimenter by pretending to continue the experiment. In the variation where the learner's physical immediacy was closest, where participants had to hold the learner's arm physically onto a shock plate, compliance decreased. Under that condition, thirty percent of participants completed the experiment.

In Experiment 8, an all-female contingent was used; previously, all participants had been men. Obedience did not significantly differ, though the women communicated experiencing higher levels of stress.

Experiment 10 took place in a modest office in Bridgeport, Connecticut, purporting to be the commercial entity "Research Associates of Bridgeport" without apparent connection to Yale University, to eliminate the university's prestige as a possible factor influencing the participants' behavior. In those conditions, obedience dropped to 47.5 percent, though the difference was not statistically significant.

Milgram also combined the effect of authority with that of conformity. In those experiments, the participant was joined by one or two additional "teachers" (also actors, like the "learner"). The behavior of the participants' peers strongly affected the results. In Experiment 17, when two additional teachers refused to comply, only 4 of 40 participants continued in the experiment. In Experiment 18, the participant performed a subsidiary task (reading the questions via microphone or recording the learner's answers) with another "teacher" who complied fully. In that variation, 37 of 40 continued with the experiment.[30]

Replications

Around the time of the release of Obedience to Authority in 1973–74, a version of the experiment was conducted at La Trobe University in Australia. As reported by Perry in her 2012 book Behind the Shock Machine, some of the participants experienced long-lasting psychological effects, possibly due to the lack of proper debriefing by the experimenter.[31]

In 2002, the British artist Rod Dickinson created The Milgram Re-enactment, an exact reconstruction of parts of the original experiment, including the uniforms, lighting, and rooms used. An audience watched the four-hour performance through one-way glass windows.[32][33] A video of this performance was first shown at the CCA Gallery in Glasgow in 2002.

A partial replication of the experiment was staged by British illusionist Derren Brown and broadcast on UK's Channel 4 in The Heist (2006).[34]

Another partial replication of the experiment was conducted by Jerry M. Burger in 2006 and broadcast on the Primetime series Basic Instincts. Burger noted that "current standards for the ethical treatment of participants clearly place Milgram's studies out of bounds." In 2009, Burger was able to receive approval from the institutional review board by modifying several of the experimental protocols.[35] Burger found obedience rates virtually identical to those reported by Milgram found in 1961–62, even while meeting current ethical regulations of informing participants. In addition, half the replication participants were female, and their rate of obedience was virtually identical to that of the male participants. Burger also included a condition in which participants first saw another participant refuse to continue. However, participants in this condition obeyed at the same rate as participants in the base condition.[36]

In the 2010 French documentary Le Jeu de la Mort (The Game of Death), researchers recreated the Milgram experiment with an added critique of reality television by presenting the scenario as a game show pilot. Volunteers were given €40 and told they would not win any money from the game, as this was only a trial. Only 16 of 80 "contestants" (teachers) chose to end the game before delivering the highest-voltage punishment.[37][38]

The experiment was performed on Dateline NBC on an episode airing April 25, 2010.

The Discovery Channel aired the "How Evil are You" segment of Curiosity on October 30, 2011. The episode was hosted by Eli Roth, who produced results similar to the original Milgram experiment, though the highest-voltage punishment used was 165 volts, rather than 450 volts.[39]

Due to increasingly widespread knowledge of the experiment, recent replications of the procedure have had to ensure that participants were not previously aware of it.

Other variations

Charles Sheridan and Richard King (at the University of Missouri and the University of California, Berkeley, respectively) hypothesized that some of Milgram's subjects may have suspected that the victim was faking, so they repeated the experiment with a real victim: a "cute, fluffy puppy" who was given real, albeit apparently harmless, electric shocks. Their findings were dissimilar to those of Milgram: half of the male subjects and all of the females obeyed throughout. Many subjects showed high levels of distress during the experiment, and some openly wept. In addition, Sheridan and King found that the duration for which the shock button was pressed decreased as the shocks got higher, meaning that for higher shock levels, subjects were more hesitant.[40][41]

Media depictions

- Obedience is a black-and-white film of the experiment, shot by Milgram himself. It is distributed by Alexander Street Press.[42]

- The Tenth Level was a 1975 CBS television film about the experiment, featuring William Shatner, Ossie Davis, and John Travolta.[10][43]

- I as in Icarus is a 1979 French conspiracy thriller with Yves Montand as a lawyer investigating the assassination of the President. The movie is inspired by the Kennedy assassination and the subsequent Warren Commission investigation. Digging into the psychology of the Lee Harvey Oswald type character, the attorney finds out the "decoy shooter" participated in the Milgram experiment. The ongoing experiment is presented to the unsuspecting lawyer.

- Foolin Around is a 1980 movie starring Gary Busey and Annette O'Toole, which uses a Milgram experiment parody in a comedic scene.

- The track "We Do What We're Told (Milgram's 37)" on Peter Gabriel's 1986 album So is a reference to Milgram's Experiment 18, in which 37 of 40 people were prepared to administer the highest level of shock.

- Referenced in Alan Moore's graphic novel V for Vendetta (1988-1989) as a reason why Dr. Surridge has lost faith in humanity.

- Atrocity is a 2005 film re-enactment of the Milgram Experiment.[44]

- The Human Behavior Experiments is a 2006 documentary by Alex Gibney about major experiments in social psychology, shown along with modern incidents highlighting the principles discussed. Along with Stanley Milgram's study in obedience, the documentary shows the diffusion of responsibility study of John Darley and Bibb Latané and the Stanford Prison Experiment of Philip Zimbardo.

- A 2006 Derren Brown special named The Heist repeated the Milgram experiment to test whether the participants will take part in a staged heist afterwards.[45]

- Chip Kidd's 2008 novel The Learners is about the Milgram experiment and features Stanley Milgram as a character.

- The Milgram Experiment is a 2009 film by the Brothers Gibbs that chronicles the story of Stanley Milgram's experiments.

- The 2008 Dar Williams song "Buzzer" is about the experiment. "I'm feeling sorry for this guy that I pressed to shock / He gets the answers wrong I have to up the watts / And he begged me to stop but they told me to go / I pressed the buzzer."

- "Authority", a 2008 episode of Law & Order: Special Victims Unit, features Merrit Rook, a suspect played by Robin Williams, who employs the strip search prank call scam, identifying himself as "Detective Milgram". He later reenacts a version of the Milgram experiment on Det. Elliot Stabler by ordering him to administer electric shocks to Det. Olivia Benson, whom Rook has bound and is thus helpless.

- Episode 114 of the 2009 Howie Mandel show Howie Do It repeated the experiment with a single pair of subjects using the premise of a Japanese game show.

- The 2010 film Zenith references and dramatically depicts the Milgram experiment

- The 2010 video game Fallout: New Vegas featured a place called the "Vault 11,' inspired by the Milgram experiment, which demanded the residents to sacrifice one of their own once a year and told them they would be exterminated if they failed to comply.

- The Discovery Channel's Curiosity TV series October 30, 2011 episode, "How Evil Are You?" features Eli Roth recreating the experiment asking the question, "Fifty years later, have we changed?"

- The 2012 film Compliance, written and directed by Craig Zobel, shows a group of employees assisting in the interrogation of a young counter assistant at the commands of a person who claims to be a police officer over the phone, demonstrating the willingness of subjects to follow orders from authority figures.

- The Fox TV series Bones featured a December 4, 2014 episode titled "The Mutilation of the Master Manipulator," where the murder victim, a college psychology professor, is shown administering the Milgram experiment.

- Experimenter, a 2015 film about Milgram, by Michael Almereyda, was screened to favorable reactions at the 2015 Sundance Film Festival.[46]

See also

- Authority bias

- Banality of evil

- Belief perseverance

- Hofling hospital experiment

- Human experimentation in the United States

- Law of Due Obedience

- Little Eichmanns

- Moral disengagement

- My Lai massacre

- Obedience (human behavior)

- Social influence

- Stanford prison experiment

- Superior orders

- The Third Wave (experiment)

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Milgram, Stanley (1963). "Behavioral Study of Obedience". Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology. 67 (4): 371–8. doi:10.1037/h0040525. PMID 14049516. as PDF.

- ↑ Milgram, Stanley (1974). Obedience to Authority; An Experimental View. Harpercollins. ISBN 0-06-131983-X.

- ↑ Zimbardo, Philip. "When Good People Do Evil". Yale Alumni Magazine. Yale Alumni Publications, Inc. Retrieved 24 April 2015.

- ↑ Search inside (2013). "Could it be that Eichmann and his million accomplices in the Holocaust were just following orders? Could we call them all accomplices?". Google Books. Retrieved 20 July 2013.

- ↑ Blass, Thomas (1991). "Understanding behavior in the Milgram obedience experiment: The role of personality, situations, and their interactions" (PDF). Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 60 (3): 398–413. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.60.3.398.

- ↑ Milgram, Stanley (1965). "Some Conditions of Obedience and Disobedience to Authority". Human Relations. 18 (1): 57–76. doi:10.1177/001872676501800105.

- ↑ Milgram, Stanley (1974). "The Perils of Obedience". Harper's Magazine. Archived from the original on December 16, 2010. Abridged and adapted from Obedience to Authority.

- ↑ Milgram 1974

- ↑ Blass, Thomas (1999). "The Milgram paradigm after 35 years: Some things we now know about obedience to authority". Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 29 (5): 955–978. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.1999.tb00134.x. as PDF

- 1 2 Blass, Thomas (Mar–Apr 2002). "The Man Who Shocked the World". Psychology Today. 35 (2).

- ↑ Discovering Psychology with Philip Zimbardo Ph.D. Updated Edition, "Power of the Situation," http://video.google.com/videoplay?docid=-6059627757980071729, reference starts at 10min 59 seconds into video.

- ↑ Milgram films. Accessed 4 October 2006.

- ↑ Milgram 1974, p. 195

- ↑ Raiten-D'Antonio, Toni (1 September 2010). Ugly as Sin: The Truth about How We Look and Finding Freedom from Self-Hatred. HCI. p. 89. ISBN 978-0-7573-1465-0.

- ↑ Milgram 1974, p. 200

- ↑ Perry, Gina (2013). Behind the Shock Machine: The Untold Story of the Notorious Milgram Psychology Experiments. New York: The New Press. pp. 79–80. ISBN 978-1-59558-925-5.

- ↑ Dimow, Joseph. "Resisting Authority: A Personal Account of the Milgram Obedience Experiments", Jewish Currents, January 2004.

- ↑ Perry, Gina. 2013. "Deception and Illusion in Milgram’s Accounts of the Obedience Experiments.” Theoretical and Applied Ethics, University of Nebraska Press Volume 2, Number 2, Winter 2013: 82. Accessed October 25, 2016.

- 1 2 James Waller (Feb 22, 2007). "What Can the Milgram Studies Teach Us..." (Google Book). Becoming Evil: How Ordinary People Commit Genocide and Mass Killing. Oxford University Press. pp. 111–113. ISBN 0199774854. Retrieved June 9, 2013.

- ↑ Blass, Thomas (2013). "The Roots of Stanley Milgram's Obedience Experiments and Their Relevance to the Holocaust" (PDF file, direct download 733 KB). Analyse und Kritik.net. p. 51. Retrieved 20 July 2013.

- ↑ Gina Perry (2012) Behind the Shock Machine: the untold story of the notorious Milgram psychology experiments, New Press. ISBN 978-1921844553.

- ↑ "Source: A cognitive reinterpretation of Stanley Milgram's observations on obedience to authority". American Psychologist. 45: 1384–1385. 1990. doi:10.1037/0003-066x.45.12.1384.

- ↑ Shiller, Robert (2005). Irrational Exuberance (2nd ed.). Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press. p. 158.

- ↑ Slater M, Antley A, Davison A, et al. (2006). Rustichini A, ed. "A virtual reprise of the Stanley Milgram obedience experiments". PLoS ONE. 1 (1): e39. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0000039. PMC 1762398

. PMID 17183667.

. PMID 17183667.

- ↑ Nissani, Moti. "A cognitive reinterpretation of Stanley Milgram's observations on obedience to authority". American Psychologist. 45: 1384–1385. doi:10.1037/0003-066x.

- ↑ Presenter: Michael Portillo. Producer: Diene Petterle. (12 May 2009). "How Violent Are You?". Horizon. Series 45. Episode 18. BBC. BBC Two. Retrieved 8 May 2013.

- ↑ Haslam, S. Alexander; Reicher, Stephen D.; Birney, Megan E. (2014-09-01). "Nothing by Mere Authority: Evidence that in an Experimental Analogue of the Milgram Paradigm Participants are Motivated not by Orders but by Appeals to Science". Journal of Social Issues. 70 (3): 473–488. doi:10.1111/josi.12072. ISSN 1540-4560.

- ↑ Haslam, S Alexander; Reicher, Stephen D; Birney, Megan E (2016-10-01). "Questioning authority: new perspectives on Milgram's 'obedience' research and its implications for intergroup relations". Current Opinion in Psychology. Intergroup relations. 11: 6–9. doi:10.1016/j.copsyc.2016.03.007.

- ↑ Cheetham, Marcus; Pedroni, Andreas; Antley, Angus; Slater, Mel; Jäncke, Lutz; Cheetham, Marcus; Pedroni, Andreas F.; Antley, Angus; Slater, Mel (2009-01-01). "Virtual milgram: empathic concern or personal distress? Evidence from functional MRI and dispositional measures". Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 3: 29. doi:10.3389/neuro.09.029.2009. PMC 2769551

. PMID 19876407.

. PMID 19876407. - ↑ Milgram, old answers. Accessed 4 October 2006. Archived April 30, 2009, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Elliott, Tim (2012-04-26). "Dark legacy left by shock tactics". Sydney Morning Herald.

- ↑ History Will Repeat Itself: Strategies of Re-enactment in Contemporary (Media) Art and Performance, ed. Inke Arns, Gabriele Horn, Frankfurt: Verlag, 2007

- ↑ "The Milgram Re-enactment". Retrieved 2008-06-10.

- ↑ "The Milgram Experiment on YouTube". Retrieved 2008-12-21.

- ↑ Burger, Jerry M. (2008). "Replicating Milgram: Would People Still Obey Today?" (PDF). American Psychologist. 64: 1–11. doi:10.1037/a0010932. PMID 19209958.

- ↑ "The Science of Evil". Retrieved 2007-01-04.

- ↑ "Fake TV Game Show 'Tortures' Man, Shocks France". Retrieved 2010-10-19.

- ↑ "Fake torture TV 'game show' reveals willingness to obey". 2010-03-17. Retrieved 2010-03-18.

- ↑ "Curiosity: How evil are you?". Retrieved 2014-04-17.

- ↑ "Sheridan & King (1972) – Obedience to authority with an authentic victim, Proceedings of the 80th Annual Convention of the American Psychological Association 7: 165–6." (PDF). Retrieved 2013-03-03.

- ↑ Blass 1999, p. 968

- ↑ "The Stanley Milgram Films on Social Psychology by Alexander Street Press".

- ↑ The Tenth Level at the Internet Movie Database. Accessed 4 October 2006.

- ↑ "Atrocity.". Archived from the original on 2007-04-27. Retrieved 2007-03-20.

- ↑ "The Heist « Derren Brown".

- ↑ "'Experimenter': Sundance Review". The Hollywood Reporter. January 28, 2015. Retrieved January 30, 2015.

References

- Blass, Thomas (2004). The Man Who Shocked the World: The Life and Legacy of Stanley Milgram. Basic Books. ISBN 0-7382-0399-8.

- Levine, Robert V. (July–August 2004). "Milgram's Progress". American Scientist. Book review of The Man Who Shocked the World

- Miller, Arthur G. (1986). The obedience experiments: A case study of controversy in social science. New York: Praeger.

- Parker, Ian (Autumn 2000). "Obedience". Granta (71). Includes an interview with one of Milgram's volunteers, and discusses modern interest in, and scepticism about, the experiment.

- Tarnow, Eugen. "Towards the Zero Accident Goal: Assisting the First Officer Monitor and Challenge Captain Errors". Journal of Aviation/Aerospace Education and Research. 10 (1).

- Tumanov, Vladimir (2007). "Stanley Milgram and Siegfried Lenz: An Analysis of Deutschstunde in the Framework of Social Psychology" (PDF). Neophilologus: International Journal of Modern and Mediaeval Language and Literature. 91 (1): 135–148. doi:10.1007/s11061-005-4254-x.

- Wu, William (June 2003). "Compliance: The Milgram Experiment". Practical Psychology.

Further reading

- Perry, Gina (2013). Behind the shock machine : the untold story of the notorious Milgram psychology experiments (Rev. edition. ed.). New York [etc.]: The New Press. ISBN 1-59558-921-X.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Milgram experiment |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Milgram experiment. |

- Stanley Milgram Redux, TBIYTB — Description of a 2007 iteration of Milgram's experiment at Yale University, published in The Yale Hippolytic, Jan. 22, 2007. (Internet Archive)

- A Powerpoint presentation describing Milgram's experiment

- Synthesis of book A faithful synthesis of Obedience to Authority – Stanley Milgram

- Obedience To Authority — A commentary extracted from 50 Psychology Classics (2007)

- A personal account of a participant in the Milgram obedience experiments

- Summary and evaluation of the 1963 obedience experiment

- The Science of Evil from ABC News Primetime

- The Lucifer Effect: How Good People Turn Evil — Video lecture of Philip Zimbardo talking about the Milgram Experiment.

- Zimbardo, Philip (2007). "When Good People Do Evil". Yale Alumni Magazine. — Article on the 45th anniversary of the Milgram experiment.

- Riggenbach, Jeff (August 3, 2010). "The Milgram Experiment". Mises Daily. Ludwig von Mises Institute.

- Milgram 1974, Chapter 1 and 15

- People 'still willing to torture' BBC

- Beyond the Shock Machine, a radio documentary with the people who took part in the experiment. Includes original audio recordings of the experiment