Nuclear weapons debate

The nuclear weapons debate refers to the controversies surrounding the threat, use and stockpiling of nuclear weapons. Even before the first nuclear weapons had been developed, scientists involved with the Manhattan Project were divided over the use of the weapon. The only time nuclear weapons have been used in warfare was during the final stages of World War II when United States Army Air Forces B-29 Superfortress bombers dropped atomic bombs on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in early August 1945. The role of the bombings in Japan's surrender and the U.S.'s ethical justification for them have been the subject of scholarly and popular debate for decades.

Nuclear disarmament refers both to the act of reducing or eliminating nuclear weapons and to the end state of a nuclear-free world. Proponents of disarmament typically condemn a priori the threat or use of nuclear weapons as immoral and argue that only total disarmament can eliminate the possibility of nuclear war. Critics of nuclear disarmament say that it would undermine deterrence and make conventional wars more likely, more destructive, or both. The debate becomes considerably complex when considering various scenarios for example, total vs partial or unilateral vs multilateral disarmament.

History

Even before the first nuclear weapons had been developed, scientists involved with the Manhattan Project were divided over the use of the weapon. Some—notably a number at the University of Chicago Metallurgical Laboratory, represented in part by Leó Szilárd—lobbied early on that the atomic bomb should only be built as a deterrent against Nazi Germany getting a bomb, and should not be used against populated cities. The Franck Report argued in June 1945 that instead of being used against a city, the first atomic bomb should be "demonstrated" to the Japanese on an uninhabited area.[1] This recommendation was not agreed with by the military commanders, the Los Alamos Target Committee (made up of other scientists), or the politicians who had input into the use of the weapon. Because the Manhattan Project was considered to be "top secret", there was no public discussion of the use of nuclear arms, and even within the U.S. government, knowledge of the bomb was extremely limited.

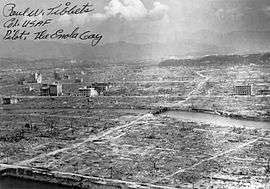

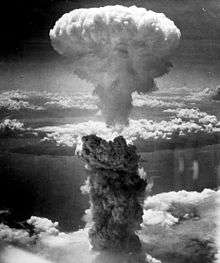

The Little Boy atomic bomb was detonated over the Japanese city of Hiroshima on 6 August 1945. Exploding with a yield equivalent to 12,500 tonnes of TNT, the blast and thermal wave of the bomb destroyed nearly 50,000 buildings (including the headquarters of the 2nd General Army and Fifth Division) and killed approximately 75,000 people, among them 20,000 Japanese soldiers and 20,000 Koreans.[2] Detonation of the "Fat Man" atomic bomb exploded over the Japanese city of Nagasaki three days later on 9 August 1945, destroying 60% of the city and killing approximately 35,000 people, among them 23,200-28,200 Japanese civilian munitions workers and 150 Japanese soldiers.[3] The role of the bombings in Japan's surrender and the U.S.'s ethical justification for them has been the subject of scholarly and popular debate for decades. J. Samuel Walker suggests that "the controversy over the use of the bomb seems certain to continue".[4]

After the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the world’s nuclear weapons stockpiles grew,[5] and nuclear weapons have been detonated on over two thousand occasions for testing and demonstration purposes. Countries known to have detonated nuclear weapons—and that acknowledge possessing such weapons—are (chronologically) the United States, the Soviet Union (succeeded as a nuclear power by Russia), the United Kingdom, France, the People's Republic of China, India, Pakistan, and North Korea.[6]

In the early 1980s, following a revival of the nuclear arms race, a popular nuclear disarmament movement emerged. In October 1981 half a million people took to the streets in several cities in Italy, more than 250,000 people protested in Bonn, 250,000 demonstrated in London, and 100,000 marched in Brussels.[7] The largest anti-nuclear protest was held on June 12, 1982, when one million people demonstrated in New York City against nuclear weapons.[8][9][10] In October 1983, nearly 3 million people across western Europe protested nuclear missile deployments and demanded an end to the arms race.[11]

Arguments

Under the scenario of total multilateral disarmament, there is no possibility of nuclear war. Under scenarios of partial disarmament there is disagreement as to how the probability of nuclear war would change. Critics of nuclear disarmament say that it would undermine the ability of governments to threaten sufficient retaliation upon attack to deter aggression against them. Application of game theory to questions of strategic nuclear warfare during the Cold War resulted in the doctrine of mutually assured destruction (MAD), a concept developed, by Robert S. McNamara, among others, in the mid-1960s.[12] The success of MAD in averting nuclear war was theorized to depend upon the “readiness at any time before, during, or after an attack to destroy the adversary as a functioning society."[13] Those who believe governments should develop or maintain nuclear-strike capability, usually justify their position with reference to MAD and the Cold War, claiming that a "nuclear peace" was the result of both the U.S. and the U.S.S.R. possessing mutual second-strike retaliation capability. Since the end of the cold war, theories of deterrence in international relations have been further developed and generalized in the concept of the stability–instability paradox[14][15] Proponents of disarmament call into question the assumption that political leaders are rational actors who place the protection of their citizens above other considerations, and highlight, as McNamara himself later acknowledged with the benefit of hindsight, the non-rational choices, chance and contingency which played a significant role in averting nuclear war, for example during the Cuban missile crisis of 1962 and the Able Archer 83 crisis of 1983,[16] thus, they argue, evidence trumps theory and deterrence theories cannot be reconciled with the historical record.

Kenneth Waltz argues in favor of the continued proliferation of nuclear weapons[17] In the July 2012 issue of Foreign Affairs Waltz took issue with the view of most U.S., European, and Israeli, commentators and policymakers that a nuclear-armed Iran would be unacceptable. Instead Waltz argues that it would probably be the best possible outcome, as it would restore stability to the Middle East by balancing Israel's regional monopoly on nuclear weapons.[18] Professor John Mueller of Ohio State University, author of Atomic Obsession[19] has also dismissed the need to interfere with Iran's nuclear program and expressed that arms control measures are counterproductive.[20] During a 2010 lecture at the University of Missouri, which was broadcast by C-Span, Dr. Mueller has also argued that the threat from nuclear weapons, including that from terrorists, has been exaggerated, both in the popular media, and by officials.[21]

In contrast, various American government officials, including Henry Kissinger, George Shultz, Sam Nunn, and William Perry.[22][23] who were in office during the Cold War period, are now advocating the elimination of nuclear weapons in the belief that the doctrine of mutual Soviet-American deterrence is obsolete, and that reliance on nuclear weapons for deterrence is becoming increasingly hazardous and decreasingly effective in the post cold war era[22] A 2011 article in The Economist argues along similar lines, that risks are more acute in rivalries between relatively new nuclear states that lack the "security safeguards" developed by America and the Soviet Union and that additional risks are posed by the emergence of pariah states, such as North Korea (possibly soon to be joined by Iran), armed with nuclear weapons as well as the declared ambition of terrorists to steal, buy or build a nuclear device.[24]

See also

- Agency for the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons in Latin America and the Caribbean

- Anti-nuclear protests in the United States

- Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty

- Debate over the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

- Effects of nuclear explosions

- Effects of nuclear explosions on human health

- History of the anti-nuclear movement

- International Court of Justice advisory opinion on legality of nuclear weapons

- Lists of nuclear disasters and radioactive incidents

- List of states with nuclear weapons

- List of nuclear weapons

- List of nuclear close calls

- Nth Country Experiment

- Nuclear disarmament

- Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty

- Nuclear peace

- Nuclear power debate

- Nuclear proliferation

- Nuclear Tipping Point

- Nuclear weapons and the United Kingdom

- Nuclear weapons and the United States

- Strategic Arms Limitation Talks

- Three Non-Nuclear Principles, of Japan

- United Nations Security Council Resolution 1194

- Uranium mining debate

References

- ↑ Schollmeyer, Josh (January–February 2005). "Minority Report". "Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists". Retrieved 2009-08-04. External link in

|publisher=(help) - ↑ Emsley, John (2001). "Uranium". Nature's Building Blocks: An A to Z Guide to the Elements. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 478. ISBN 0-19-850340-7.

- ↑ Nuke-Rebuke: Writers & Artists Against Nuclear Energy & Weapons (The Contemporary anthology series). The Spirit That Moves Us Press. May 1, 1984. pp. 22–29.

- ↑ Walker, J. Samuel (April 2005). "Recent Literature on Truman's Atomic Bomb Decision: A Search for Middle Ground". Diplomatic History. 29 (2): 334. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7709.2005.00476.x.

- ↑ Mary Palevsky, Robert Futrell, and Andrew Kirk. Recollections of Nevada's Nuclear Past UNLV FUSION, 2005, p. 20.

- ↑ "Federation of American Scientists: Status of World Nuclear Forces". Fas.org. Retrieved 2010-01-12.

- ↑ David Cortright (2008). Peace: A History of Movements and Ideas, Cambridge University Press, p. 147.

- ↑ Jonathan Schell. The Spirit of June 12 The Nation, July 2, 2007.

- ↑ David Cortright (2008). Peace: A History of Movements and Ideas, Cambridge University Press, p. 145.

- ↑ 1982 - a million people march in New York City

- ↑ David Cortright (2008). Peace: A History of Movements and Ideas, Cambridge University Press, p. 148.

- ↑ Elliot, Jeffrey M. and Robert Reginald. (1989). The Arms Control, Disarmament, and Military Security Dictionary, Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO, Inc.

- ↑ Gertcher, Frank L., and William J. Weida. (1990). Beyond Deterrence, Boulder: Westview Press, Inc.

- ↑ http://www.stimson.org/images/uploads/research-pdfs/ESCCONTROLCHAPTER1.pdf

- ↑ Krepon, Michael (November 2, 2010). "The Stability-Instability Paradox". Arms Control Wonk. Retrieved 2016-10-04.

- ↑ James G Blight, Janet M. Lang. The Fog of War: Lessons from the Life of Robert S. McNamara, page 60.

- ↑ Waltz, Kenneth (1981). "The Spread of Nuclear Weapons: More May Be Better". Adelphi Papers. London: International Institute for Strategic Studies (171).

- ↑ Waltz, Kenneth (July–August 2012). "Why Iran Should Get the Bomb: Nuclear Balancing Would Mean Stability". Foreign Affairs.

- ↑ "Atomic Obsession - Hardback - John Mueller - Oxford University Press".

- ↑ Bloggingheads.tv from 19:00 to 26:00 minutes

- ↑ "[Atomic Obsession]". C-SPAN.org. Retrieved 2016-10-04.

- 1 2 George P. Shultz, William J. Perry, Henry A. Kissinger and Sam Nunn. A World Free of Nuclear Weapons Wall Street Journal, January 4, 2007, page A15.

- ↑ Hugh Gusterson (30 March 2012). "The new abolitionists". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists.

- ↑ "Nuclear endgame: The growing appeal of zero". The Economist. June 16, 2011.

Further reading

- M. Clarke and M. Mowlam (Eds) (1982). Debate on Disarmament, Routledge and Kegan Paul.

- Cooke, Stephanie (2009). In Mortal Hands: A Cautionary History of the Nuclear Age, Black Inc.

- Falk, Jim (1982). Global Fission: The Battle Over Nuclear Power, Oxford University Press.

- Murphy, Arthur W. (1976). The Nuclear Power Controversy, Prentice-Hall.

- Malheiros, Tania. Brasiliens geheime Bombe: Das brasilianische Atomprogramm. Tradução: Maria Conceição da Costa e Paulo Carvalho da Silva Filho. Frankfurt am Main: Report-Verlag, 1995.

- Malheiros, Tania. Brasil, a bomba oculta: O programa nuclear brasileiro. Rio de Janeiro: Gryphus, 1993. (Portuguese)

- Malheiros, Tania. Histórias Secretas do Brasil Nuclear. (WVA Editora; ISBN 85-85644087) (Portuguese)

- Walker, J. Samuel (2004). Three Mile Island: A Nuclear Crisis in Historical Perspective, University of California Press.

- Williams, Phil (Ed.) (1984). The Nuclear Debate: Issues and Politics, Routledge & Keagan Paul, London.

- Wittner, Lawrence S. (2009). Confronting the Bomb: A Short History of the World Nuclear Disarmament Movement, Stanford University Press.