Nubar Gulbenkian

| Nubar Gulbenkian | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

Nubar Sarkis Gulbenkian 2 June 1896 Kadıköy, Ottoman Empire[1] |

| Died |

10 January 1972 (aged 75) Cannes, France |

| Nationality | British |

| Occupation | Businessman |

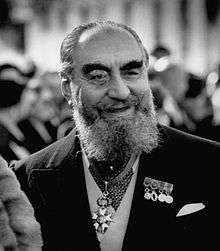

Nubar Sarkis Gulbenkian (Armenian: Նուպար Սարգիս Կիւլպէնկեան; 2 June 1896 – 10 January 1972) was an Armenian business magnate and socialite[2] born in the Ottoman empire.

Early years

The son of Calouste Gulbenkian, he was born in Kadıköy, Ottoman Empire but fled from the country when he was a few weeks old due to the Hamidian massacres of Armenians.[3] Taken by his father to England, he was educated at Harrow School, Trinity College, Cambridge and in Germany. As a consequence of his educational background Gulbenkian saw himself as British and strove to live up to the model of the English gentleman. As such, during World War II he undertook some amateur sabotage in Vichy France on behalf of the United Kingdom.[4] Despite this he was also attached to the Iranian Embassy in London in an honorary role (as he held Iranian citizenship) whilst he regained his Turkish citizenship in 1965.[5] This however had helped him during the war as his neutral passport allowed him to cross between France and Spain with little trouble and thus gain access to British intelligence in Gibraltar.[6]

Business

Gulbenkian began as an unpaid worker for his father, who was as noted for his miserly tendencies as his son would be for his spending, but later sued his father for $10 million, bizarrely after a refusal by the company to allow him $4.50 for a lunch of chicken in tarragon jelly.[5] Ultimately the incident contributed to Calouste Gulbenkian's decision to leave $420 million of his fortune to the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation in Portugal.[5]

Although he ultimately inherited $2.5 million from his father, as well as more in a settlement from the Foundation, Gulbenkian also became independently wealthy through his own oil dealings.[5] He was initially the protégé of Henri Deterding at Royal Dutch Shell[4] but later made an independent fortune which allowed him to live a highly extravagant lifestyle.

Eccentricity

Gulbenkian's long beard, monocle and the orchid in his buttonhole which was replaced daily led to him becoming noted for a fairly eccentric life, with a number of stories building up around his name. Indeed his character was summed up by an associate who claimed that "Nubar is so tough that every day he tires out three stockbrokers, three horses and three women".[5] He was a regular face on the international playboy scene.

An aficionado of the Hackney carriage, he frequently stated that 'It turns on a sixpence, whatever that is!' He even had two Austin FX4 cabs converted to his own specifications and, despite their somewhat bizarre appearance, one of the vehicles sold for £23,000 in 1993.[7]

He was an early guest on the BBC series Face to Face in 1959, but refused to sign a contract or accept a fee for his appearance. During the interview he attacked the Trustees of the Gulbenkian Foundation in what amounted to virtual slander.[8] Following his appearance, he sued the Corporation in order to be given a copy of the episode, which he claimed had been promised in lieu of a fee, although the suit was not successful.[9]

A known gourmet, he was quoted as saying that 'the best number for a dinner party is two - myself and a damn good head waiter.'[10] Other stories attached to his name include giving his position in life on a market research form as 'enviable'.

Will

Controversy continued to follow him after his death due to the vague nature of his father's will, which appeared to suggest that everybody Nubar was employed by or stayed with during his life should receive some money (See Re Gulbenkian's Settlements [1970] AC 553). The case was eventually taken to the House of Lords before settlement.[11]

References

- ↑ "Obits: "Gu" - "Gz"". Caskets On Parade. C.O.P. Audit Committee. 2007-04-01. Retrieved 2008-01-28.

- ↑ "A man with a passion for Rollers". Telegraph. 2004-02-14. Retrieved 2016-03-09.

- ↑ Gulbenkian, Nubar S. (1965). Pantaraxia: The Autobiography of Nubar Gulbenkian. Hutchinson & Company. p. 10.

I was their first-born. I was only a few weeks old when we left Kadi Keui and fled from Turkey, for the year 1896 was the time of the Armenian massacres.

- 1 2 N. Gulbenkian, Portrait in Oil: The Autobiography of Nubar Gulbenkian, New York: Simon and Schuster, 1965

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Last of the Big Spenders". Time Magazine. 1972-01-24. Retrieved 2008-01-28.

- ↑ Sherri Greene Ottis, Silent Heroes: Downed Airmen and the French Underground, p. 78

- ↑ Adams, Keith (2004-08-17). "Specialist conversions". Austin Rover Online. Retrieved 2008-01-28.

- ↑ Asa Briggs The History of Broadcasting in the United Kingdom, Volume V, Oxford University Press, 1995, p. 170

- ↑ Burnett, Hugh (2007-11-23). "Nubar Gulbenkian interview". Memoryshare. BBC. Retrieved 2008-01-28.

- ↑ "Nubar Gulbenkian quotes". ThinkExist.com Quotations. Retrieved 2008-01-28.

- ↑ Alastair Hudson, Equity & Trusts, p.95