Noyon

| Noyon | ||

|---|---|---|

|

The cathedral | ||

| ||

Noyon | ||

|

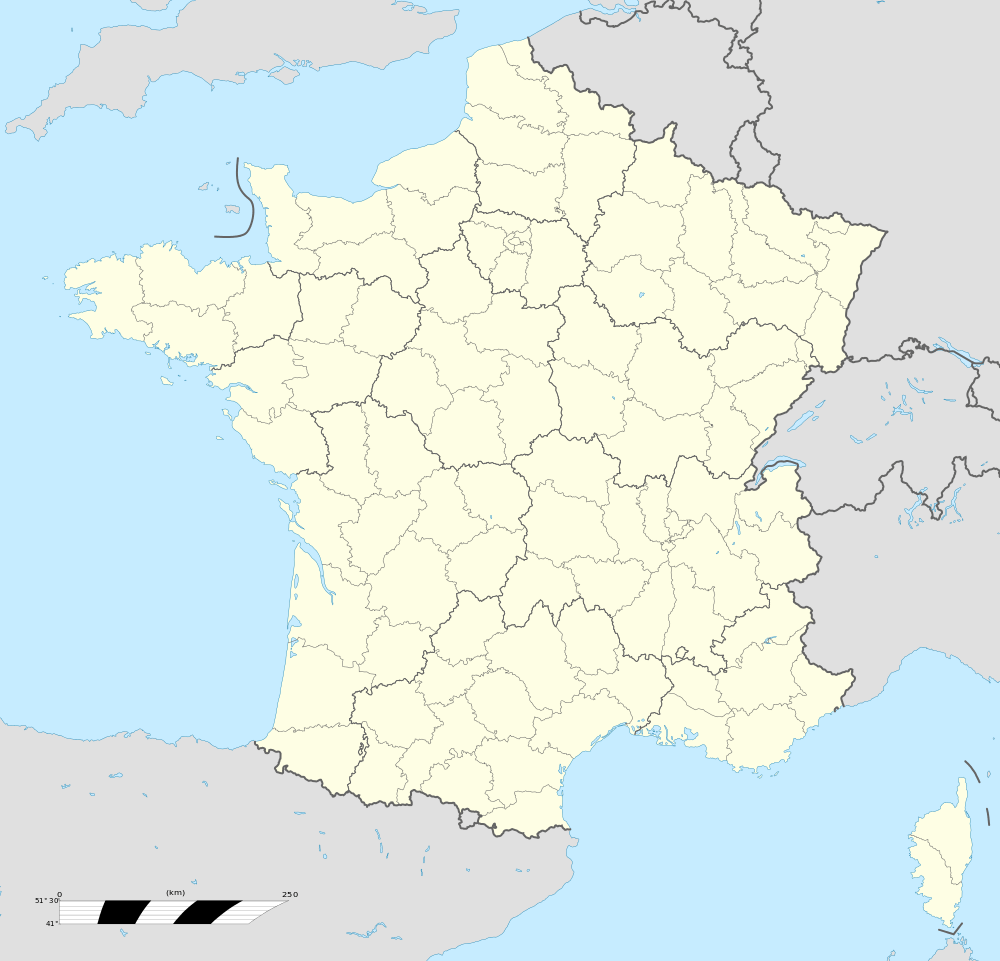

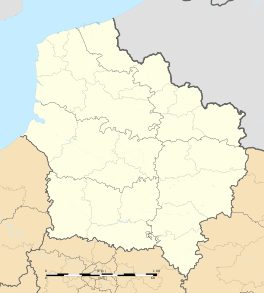

Location within Hauts-de-France region  Noyon | ||

| Coordinates: 49°34′54″N 2°59′59″E / 49.5817°N 2.9997°ECoordinates: 49°34′54″N 2°59′59″E / 49.5817°N 2.9997°E | ||

| Country | France | |

| Region | Hauts-de-France | |

| Department | Oise | |

| Arrondissement | Compiègne | |

| Canton | Noyon | |

| Intercommunality | Pays Noyonnais | |

| Government | ||

| • Mayor (2008–2014) | Patrick Deguise | |

| Area1 | 18 km2 (7 sq mi) | |

| Population (2012)2 | 13,658 | |

| • Density | 760/km2 (2,000/sq mi) | |

| Time zone | CET (UTC+1) | |

| • Summer (DST) | CEST (UTC+2) | |

| INSEE/Postal code | 60471 / 60400 | |

| Elevation |

36–153 m (118–502 ft) (avg. 52 m or 171 ft) | |

|

1 French Land Register data, which excludes lakes, ponds, glaciers > 1 km² (0.386 sq mi or 247 acres) and river estuaries. 2 Population without double counting: residents of multiple communes (e.g., students and military personnel) only counted once. | ||

Noyon (Latin: Noviomagus Veromanduorum, Noviomagus of the Veromandui) is a commune in the Oise department in northern France. It lies on the Oise Canal about 100 kilometers (60 mi) north of Paris.

History

The Gallo-Romans founded the town as Noviomagus (Celtic for "New Field" or "Market"). As several other cities shared the name, it was distinguished by specifying the people living in and around it. The town is mentioned in the Antonine Itinerary as being 27 Roman miles from Soissons and 34 Roman miles from Amiens, but d'Anville noted that the distance must be in error, Amiens being further and Soisson closer than indicated.

By the Middle Ages, the town's Latin name had mutated to Noviomum. The town was strongly fortified; some sections of the Roman walls still remained in late antiquity. This may explain why, around the year 531, bishop Medardus moved his seat from Vermand in the Vermandois to Noyon. (Another option was to move his seat to Saint-Quentin but the wine produced in Noyon was thought to be much better than that produced in Saint-Quentin.[1] Other explanations are that Medardus was born near the town, at Salency, or that the place is nearer to Soissons, which was one of the royal capitals of the Merovingians.) The bishop of Noyon was also bishop of Tournai from the seventh century until Tournai was raised to a separate diocese 1146.[2]

The cathedral at Noyon was where Charlemagne was crowned as co-King of the Franks in 768,[3] as was the first Capetian king, Hugh Capet in 987.[4] In 859 the town was attacked by Vikings[5] and the bishop, Immo, captured and killed.[6] The town received a communal charter in 1108, which was later confirmed by Philip Augustus in 1223. In the twelfth century, the diocese of Noyon was raised to an ecclesiastical duchy in the peerage of France. The Romanesque cathedral was destroyed by fire in 1131, but soon replaced by the present cathedral, Notre-Dame de Noyon, constructed between 1145 and 1235, one of the earliest examples of Gothic architecture in France. The bishop's library is a historic example of half-timbered construction.

By the Treaty of Noyon, signed on the 13 August 1516 between Francis I of France and emperor Charles V, France abandoned its claims to the Kingdom of Naples and received the Duchy of Milan in recompense. The treaty brought the War of the League of Cambrai— one stage of the Italian Wars— to a close.

During King Henry II's Italian war in 1557, most of Noyon would be burned,[7] in the midst of Philip II of Spain's invasion of Picardy,[8] before returning to their winter quarters in the Spanish Netherlands.[8]

Near the end of the sixteenth century the town fell under Habsburg control, but Henry IV of France recaptured it. The Concordat of 1801 suppressed its bishopric. The town was occupied by the Germans during World War I and World War II and on both occasions suffered heavy damage.

Personalities

- John Calvin was born in Noyon, 1509.

- Medardus

- Godeberta

- Jacques de Noyon

- Simon-Jérôme Bourlet de Vauxcelles (1733–1802), 18th-century French priest and journalist

International relations

Noyon is twinned with:

See also

Notes

- ↑ M. Lachiver, Vins, vignes et vignerons. Histoire du vignoble français, éditions Fayard, Paris, 1988, (ISBN 221302202X), p. 53

- ↑ Catholic Encyclopedia, s.v. Tournai [Doornik] (Diocese); Roman Catholic Diocese of Tournai.

- ↑ Peter Lasko, Ars Sacra, 800-1200, (Yale University Press, 1994), 1.

- ↑ Laon, Kim M. Magon, Northern Europe: International Dictionary of Historic Places, Vol. 2, ed. Trudy Ring, Noelle Watson, Paul Schellinger, (Routledge, 1995), 397.

- ↑ Karl Leyser, Communications and Power in Medieval Europe: The Carolingian and Ottonian Centuries, ed. Timothy Reuter, (Hambledon Press, 1994), 48 note110.

- ↑ Dudo (Dean of St. Quentin), History of the Normans, transl. Eric Christiansen, (The Boydell Press, 1998), 184 note82.

- ↑ George A. Rothrock, The Huguenots: A Biography of a Minority, (Nelson-Hall, Inc., 1979), 48.

- 1 2 A Global Chronology of Conflict: From the Ancient World to the Modern Middle East, Vol. II, ed. Spencer C. Tucker, (ABC-CLIO, 2010), 518.

References

- INSEE commune file

-

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Smith, William, ed. (1854–1857). "article name needed". Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography. London: John Murray.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Smith, William, ed. (1854–1857). "article name needed". Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography. London: John Murray.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Noyon. |

About the cathedral:

.svg.png)