New England vampire panic

The New England vampire panic was the reaction to an outbreak of tuberculosis in the 19th century throughout Rhode Island, eastern Connecticut, Vermont, and other parts of New England.[1] Consumption (tuberculosis) was thought to be caused by the deceased consuming the life of their surviving relatives.[2] Bodies were exhumed and internal organs ritually burned to stop the "vampire" from attacking the local population and to prevent the spread of the disease. Notable cases provoked national attention and comment, such as those of Mercy Brown in Rhode Island and Frederick Ransom in Vermont.

Background

Tuberculosis was known as "consumption" at the time, as it appeared to consume an infected person's body.[3] It is now known to be a bacterial disease, but the cause was unknown until the late 19th century.[4] The infection spreads easily among a family; thus, when one family member died of consumption, other members were often infected and gradually lost their health. People believed that this was due to the deceased TB sufferer draining the life from other family members.[2] The belief that consumption was spread in this way was widely held in New England[5]:214 and in Europe.[6]

In an attempt to protect the survivors and ward off the effects of consumption, bodies were exhumed and examined of those who had died of the disease. The corpse was deemed to be feeding on the living if it was determined to be unusually fresh, especially if the heart or other organs contained liquid blood. After the culprit was identified, there were a number of proposed ways to stop the attacks. The most benign of these was simply to turn the body over in its grave. In other cases, families would burn the "fresh" organs and rebury the body; occasionally, the body would be decapitated. Affected family members would also inhale smoke from the burned organs or consume the ashes in a further attempt to cure the consumption.[7]:130

Documented victims

Mercy Brown

One of the more famous cases is that of Mercy Lena Brown. Mercy's mother contracted consumption which spread to the rest of the family, moving to her sister, her brother, and finally to Mercy. Neighbors believed that one of the family members was a vampire who had the illness. Two months after Mercy's death, her father George Brown--who did not believe that a vampire was to blame--reluctantly permitted others to exhume the bodies of his family. They found that Mercy's body showed little decomposition, had "fresh" blood in her heart, and had turned in the grave.[8] This was enough to convince the villagers that Mercy Brown was the cause of the consumption. The heart of the exhumed body was burnt, mixed with water, and given to her surviving brother to drink in order to stop the influence of the undead. Unsurprisingly, the cure was unsuccessful.[1]

Frederick Ransom

Frederick Ransom of South Woodstock, Vermont died of tuberculosis on 14 February 1817 at the age of 20.[5]:238 His father was worried that Ransom would attack his family, so he had him exhumed and his heart burned on a blacksmith's forge.[9] Ransom was a Dartmouth College student from a well-to-do family; it was unusual that he should fall victim of the vampire panic, which was most common among less educated communities.[10]

Contemporary reaction

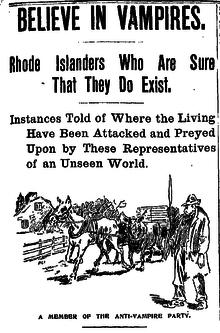

Henry David Thoreau wrote in his journal of 26 September 1859: "The savage in man is never quite eradicated. I have just read of a family in Vermont--who, several of its members having died of consumption, just burned the lungs & heart & liver of the last deceased, in order to prevent any more from having it," as a reference to contemporary superstition.[11] When rural Rhode Islanders moved west into Connecticut, locals perceived them as "uneducated" and "vicious", which was partially due to the Rhode Islanders' beliefs in vampirism.[2] Newspapers were also sceptical, calling belief in vampirism an "old superstition" and a "curious idea".[7]:132

While the press dismissed this practise as superstition, the burning of organs was widely accepted as a folk medicine in other communities. In Woodstock, where local belief was still present, town records report hundreds of onlookers attending the burning of Frederick Ransom's heart. For instance, the records report that "Timothy Mead officiated at the altar in the sacrifice to the Demon Vampire who it was believed was still sucking the blood of the then living wife of Captain Burton."[1]

Terminology

It is unlikely that the deceased would have been known as vampires by their affected families, because the word was not in common use in the community at that time. However, the term was used by newspapers and outsiders at the time due to the similarity with contemporary vampire beliefs in eastern Europe.[8]

These beliefs were very different from the vampires portrayed in modern popular culture. Michael Bell conducted an anthropological study of the phenomenon in New England, and he rejected that modern narrative: "No credible account describes a corpse actually leaving the grave to suck blood, and there is little evidence to suggest that those involved in the practice referred to it as 'vampirism' or to the suspected corpse as a 'vampire', although newspaper accounts used this term to refer to the practice."[7]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 Tucker, Abigail. "The Great New England Vampire Panic". Smithsonian magazine (October 2012). Retrieved 2012-12-02.

- 1 2 3 Sledzik, Paul S.; Nicholas Bellantoni (1994). "Bioarcheological and biocultural evidence for the New England vampire folk belief" (PDF). American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 94 (2): 269–274. doi:10.1002/ajpa.1330940210. PMID 8085617.

- ↑ "Learn the Signs and Symptoms of TB Disease" Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 18 June 2012. Web. 2 December 2012.

- ↑ Madigan, Michael T., et al. Brock Biology of Microorganisms: Thirteenth edition. Benjamin Cummings: Boston, 2012. Print.

- 1 2 Guiley, Rosemary (2005). The Encyclopedia of Vampires, Werewolves, and Other Monsters. Facts on File. ISBN 0-8160-4684-0.

- ↑ Ingber, Sasha (2012-12-17). "The Bloody Truth About Serbia's Vampire". National Geographic News. Retrieved 15 August 2013.

- 1 2 3 Bell, Michael (2006). "Vampires and Death in New England, 1784 to 1892". Anthropology and Humanism. 31 (2): 124–140. doi:10.1525/ahu.2006.31.2.124. Retrieved 16 August 2013.

- 1 2 "Interview with a REAL Vampire Stalker". SeacoastNH.com. Retrieved 2013-08-15.

- ↑ Henderson, Gareth (18 November 2010). "'History of Vampires' Recounts Woodstock Tale". Vermont Standard. Retrieved 2013-08-16.

- ↑ Tucker, Abigail. "Meet the Real-Life Vampires of New England and Abroad". Smithsonian magazine (September 2012). Retrieved 2013-08-15.

- ↑ Thoreau, Henry David, Bradford Torrey, and Francis H. Allen. "Journal." Journal. Vol. 30. New York: Dover Publications, 1962. N. pag. Print. Manuscript.