Neuromarketing

Neuromarketing is a field that claims to apply the principles of neuroscience to marketing research, studying consumers' sensorimotor, cognitive, and affective response to marketing stimuli. Researchers use technologies such as functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to measure changes in activity in parts of the brain, electroencephalography (EEG) and Steady state topography (SST) to measure activity in specific regional spectra of the brain response; sensors to measure changes in one's physiological state, also known as biometrics, including heart rate, respiratory rate, and galvanic skin response; facial coding to categorize the physical expression of emotion; or eye tracking to identify focal attention - all in order to learn why consumers make the decisions they do, and which brain areas are responsible. Certain companies, particularly those with large-scale ambitions to predict consumer behaviour, have invested in their own laboratories, science personnel or partnerships with academia.[1] Serving nearly 1,700 members in more than 90 countries, the Neuromarketing Science & Business Association[2] today centralizes academic publications and certifications and serves as a networking platform for professionals in the field.

Companies such as Google, CBS, Frito-Lay, and A & E Television amongst others have used neuromarketing research services to measure consumer reactions to their advertisements or products.[3]

In the late 1990s, both Neurosense (UK) and Gerry Zaltmann (USA) had established neuromarketing companies. In 2006, Dr. Carl Marci founded Innerscope Research, which was acquired by Nielsen[4] in May 2015 and renamed Nielsen Consumer Neuroscience. Unilever's Consumer Research Exploratory Fund (CREF) too had been publishing white papers on the potential applications of Neuromarketing.[5]

History

Neuromarketing is a reasonably new field of discovery; prior research enhanced the knowledge of consumer behaviour until the concept of neuromarketing was created. Theories behind neuromarketing were first explored by marketing professor Gerald Zaltman in the 1990s. Zaltman and his associates were employed by organizations, such as Coca Cola ltd, to instigate brain scans and observe neural activity of consumers (Kelly, 2002). Psychoanalysis techniques such as fMRI (functional magnetic resonance imagining) and other neuro-technologies are used to discover an individual's underlying emotions and social interactions as represented in the scans (Fisher, Chin and Kiltzman, 2011). Zaltman theorised a technique called ZMET; this involved using visual representations to help uncover underlying and deep thoughts within a person (Kelly, 2002). With the use of ZMET, Zaltman aimed to make powerful, emotionally completing advertising. Brain activity was recorded while participants viewed the ad, ultimately to explore and discover non-conscious thoughts of consumers. His research methods enhanced psychological research used in marketing tools (Kelly, 2002).

However the term ‘neuromarketing’ was only introduced in 2002, published in an article by BrightHouse, a marketing firm based in Atlanta (Ait Hammou, Galib & Melloul, 2013). BrightHouse sponsored neurophysiologic (nervous system functioning) research into marketing divisions; they constructed a business unit that used fMRI scans for market research purposes (Ait Hammou, Galib & Melloul, 2013). The firm rapidly attracted criticism and disapproval concerning conflict of interest with Emory University, who helped establish the division (Fisher, Chin and Kiltzman, 2011). The new enterprise disappeared from public attention and now works with over 500 clients and consumer-product businesses due to the effective method of neuromarketing (Ait Hammou, Galib & Melloul, 2013).

The neuromarketing concept

Neuromarketing, marketing designed on the foundation of neuroscience, is the most recent mechanical method utilized to understand consumers (Kolter, Burton, Deans, Brown & Armstrong, 2013).

Neuromarketing engages the use of Magnetic Resance Imaging (MRI), electroencephalography (EEG), biometrics, facial coding, eye tracking and other technologies to investigate and learn how consumers respond and feel when presented with products and/or related stimuli (Kolter et al., 2013). The concept of neuromarketing investigates the non-conscious processing of information in consumers brains (Agarwal & Dutta, 2015). Human decision-making is both a conscious and non-conscious process in the brain (Glanert, 2012). Human brains process over 90% of information non-consciously, below controlled awareness; this information has a large influence in the decision-making process (Agarwal & Dutta, 2015). Conventional market research, such as focus groups or surveys, are typically used to understand behaviour and decision-making. However these research methods do not reach the non-conscious thinking of consumers. This results in an incompatibility between market research findings and the actual behaviour exhibited by the target market at the point of purchase (Agarwal & Dutta, 2015). Neuromarketing rather focuses on the MRI and EEG scans which produce brain electrical activity as well as blood flow. Market researchers use this information to determine if products or advertisements stimulate responses in the brain linked with positive emotions (Kolter et al., 2013). The concept of neuromarketing was therefore introduced to study relevant human emotions and behavioural patterns associated with new products, ads and decision-making (Neuromarketing Science and Business Association, n.d.).

A greater understanding of human cognition and behaviour has led to the integration of biological and social sciences. Combining marketing, psychology and neuroscience, the concept of neuromarketing has established valuable theoretical insights. Consumer behaviour can now be investigated at both an individuals conscious choices and underlying brain activity levels (Shiv & Yoon, 2012). Neuromarketing displays a true representation of reality, superior to any traditional methods of research as it explores non-conscious information that would otherwise be unobtainable. The neural processes obtained provide a more accurate prediction of population-level data in comparison to self-reported data (Agarwal & Dutta, 2015). Marketers are now able to gain insight into consumers' intentions. These tools can be administered to gain understanding on intention and emotions towards branding and market strategies before applying them to target consumers (Agarwal & Dutta, 2015).

Neuromarketing is dynamic, it can relate to nearly anyone who has developed an opinion about a product or brand and has formed preferences. Marketing focuses on constructing positive and unforgettable experiences in consumers minds; it is neuroscience that measures these impacts (Venkatraman, Clithero, Fitzsimons & Huettel, 2012).

Best-known technology of neuromarketing was developed in the late 1990s by Harvard professor Jerry Zaltman (Gerald Zaltman), once it was patented under the name of Zaltman Metaphor Elicitation Technique (ZMET). The essence of ZMET reduces to exploring the human unconscious with specially selected sets of images that cause a positive emotional response and activate hidden images, metaphors stimulating the purchase.[6] Graphical collages are constructed on the base of detected images, which lays in the basis for commercials. Marketing Technology ZMET quickly gained popularity among hundreds of major companies-customers including Coca-Cola, General Motors, Nestle, Procter & Gamble.

Neuromarketing process

Collecting information on how the target market would respond to the future product is the first step involved for organisations producing a new product. Traditional methods of this research include focus groups or sizeable surveys used to evaluate features of the proposed product (Venkatraman, Clithero, Fitzsimons & Huettel, 2012). This method of research fails to gain a deep understanding of the consumer’s non-conscious thoughts and emotions (Shiv & Yoon, 2012).

Neuroscience has played an important role in improving behavioural predictions and advancing the understanding of consumers. It also allows insight into neural differences seen in individuals when no behavioural differences are observed (Agarwal & Dutta, 2015). For example, one customer may retrieve many memories when making a choice whereas another customer may not retrieve any memories. This insight allows marketers to understand the consumer’s brain activity and cognitive processes at a non-conscious level. They can then advertise the product so that it communicates and meet the needs of potential consumers with difference predictions of choice (Venkatraman, Clithero, Fitzsimons & Huettel, 2012).

In response to marketing and advertising there are only three highly established methods of measuring brain activity. These include ectroencephalography (EEG), magnetoencephalography (MEG) and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). It is important that all three methods are non-invasive as this ensures they can safely be used for market research purposes (Morin, 2011). Once appropriate information is attained regarding the proposed products, the brand manager may revise of the original product design in response to the market research. The original prototype may be modified from feedback to attract and appeal to target consumer’s conscious and non-conscious thoughts (Venkatraman, Clithero, Fitzsimons & Huettel, 2012). It is essential to understand consumers’ true wants and underlying thoughts. This results in effective marketing and advertising communications, ultimately leading to increase in successful sales (De Clerck, 2012).

System 1 and System 2

Based on the Neuromarketing concept of decision processing, consumer buying decisions rely on either System 1 or System 2 processing or Plato’s two horses and a chariot. System 1 thinking is intuitive, unconscious, effortless, fast and emotional. In contrast, decisions driven by system 2 are deliberate, conscious reasoning, slow and effortful. In consumer behavior, these processes guide everyday purchasing decisions. Nevertheless, Zurawicki (2010) believes that buying decisions are driven by one’s mood and emotions; concluding that compulsive and or spontaneous purchases are driven by system 1.

Segmentation and Positioning

Marketers use segmentation and positioning to divide the market and choose the segments they will use to position themselves to strategically target their message.[7] Using neuroscience, marketers have now been able to target and tailor their offerings to better-fit buyers expectations[8] More precise market segments can be devised by using neuroscience to cater to specific brain functions. For example, using the neurological differences between genders can alter the target market, and more precisely devise a segment.[9] Research has shown that structural differences between the male and female brain has strong influence on their respective decisions as consumers.[10] Females have a more concentrated packing power, which means they are able to concentrate on more than one task at a time (multi-tasking), and also have a ‘bigger picture’ view of the world. Males are more concentrated on minute details, and logical thinking[10] In short, woman are more ‘empathisers’ and men more ‘systemisers’ and this can be applied to segmentation as a marketer may want to target a more emotional approach product to women, as it has been proven that woman recall emotional matter 15-20% times better in the long run than males do.[10] Another example of where neural research can serve as a tool for marketers is when targeting the youth segment. Young people represent a high share of buyers in many industries including the electronics market and fashion industry.[10] Due to the development of brain maturation, adolescents are subject to strong emotional reaction, although can have difficulty identifying the emotional expression of others[11]). Marketers can use this neural information to target adolescents with shorter, attention grabbing messages, and ones that can influence their emotional expressions clearly. Teenagers rely on more ‘gut feeling’ and don’t fully think through consequences, so are mainly consumers of products based on excitement and impulse. Due to this behavioural quality, segmenting the market to target adolescent’s can be beneficial to marketers that advertise with an emotional, quick response approach.

Study Examples

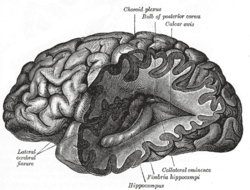

In a study from the group of Read Montague published in 2004 in Neuron,[12] 67 people had their brains scanned while being given the "Pepsi Challenge", a blind taste test of Coca-Cola and Pepsi. Half the subjects chose Pepsi, since Pepsi tended to produce a stronger response than Coke in their brain's ventromedial prefrontal cortex, a region thought to process feelings of reward. But when the subjects were told they were drinking Coke three-quarters said that Coke tasted better. Their brain activity had also changed. The lateral prefrontal cortex, an area of the brain that scientists say governs high-level cognitive powers, and the hippocampus, an area related to memory, were now being used, indicating that the consumers were thinking about Coke and relating it to memories and other impressions. The results demonstrated that Pepsi should have half the market share, but in reality consumers are buying Coke for reasons related less to their taste preferences and more to their experience with the Coke brand.

In 2013, Innerscope Research introduced the Brand Immersion Model,[13] a new, neuroscience-informed model for understanding media engagement in a multi-screen, multi-channel environment. Collaborating with companies such as FOX Broadcasting Company and Turner Broadcasting Systems, studies found that consumers' emotional engagement was much stronger with television than online viewing, but that television viewed with similar online content showed the strongest points of engagement.

Criticism

Many of the claims of companies that sell neuromarketing services make are not based on actual neuroscience and have been debunked as hype, and have been described as part of a fad of pseudoscientific "neuroscientism" in popular culture.[14][15][16] Joseph Turow, a communications professor at the University of Pennsylvania, dismisses neuromarketing as another reincarnation of gimmicky attempts for advertisers to find non-traditional approaches toward gathering consumer opinion. He is quoted in saying, "There has always been a holy grail in advertising to try to reach people in a hypodermic way. Major corporations and research firms are jumping on the neuromarketing bandwagon, because they are desperate for any novel technique to help them break through all the marketing clutter. ‘It’s as much about the nature of the industry and the anxiety roiling through the system as it is about anything else."[17]

Some consumer advocate organizations, such as the Center for Digital Democracy, have criticized neuromarketing’s potentially invasive technology. Jeff Chester, the executive director of the organization, claims that neuromarketing is “having an effect on individuals that individuals are not informed about." Further, he claims that though there has not historically been regulation on adult advertising due to adults having defense mechanisms to discern what is true and untrue, that it should now be regulated “if the advertising is now purposely designed to bypass those rational defenses . . . protecting advertising speech in the marketplace has to be questioned."[3]

Advocates nonetheless argue that society benefits from neuromarketing innovations. German neurobiologist Kai-Markus Müller promotes a neuromarketing variant, "neuropricing," that uses data from brain scans to help companies identify the highest prices consumers will pay. Müller says "everyone wins with this method," because brain-tested prices enable firms to increase profits, thus increasing prospects for survival during economic recession.[18]

See also

References

- ↑ Karmarkar, Uma R. (2011). "Note on Neuromarketing". Harvard Business School (9-512-031).

- ↑ Neuromarketing Business Association

- 1 2 Natasha Singer (3 November 2010). "Making Ads that Whisper to the Brain". The New York Times.

- ↑ http://www.forbes.com/sites/rogerdooley/2015/06/03/nielsen-doubles-down-on-neuro/#4ffaf7ee306c

- ↑ David Lewis & Darren Brigder (July–August 2005). "Market Researchers make Increasing use of Brain Imaging" (PDF). Advances in Clinical Neuroscience and Rehabilitation. 5 (3): 35+.

- ↑ "Carbone, Lou. Clued In: How to Keep Customers Coming Back Again and Again. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Financial Times Prentice Hall (2004): 140-141, 254.".

- ↑ (Kotler et al, 2013)

- ↑ (Zurawicki, 2010).

- ↑ ( Zurawicki, 2010)

- 1 2 3 4 (Zurawicki, 2010)

- ↑ (Zurawicki, 2010

- ↑ Samuel M. McClure, Jian Li, Damon Tomlin, Kim S. Cypert, Latané M. Montague, and P. Read Montague (2004). "Neural Correlates of Behavioral Preference for Culturally Familiar Drinks" (abstract). Neuron. 44 (2): 379–387. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2004.09.019. PMID 15473974.

- ↑ http://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/innerscope-research-and-fox-broadcasting-company-debut-biometric-study-scientifically-validating-the-creation-of-brand-equity-through-immersive-media-exposure-121579323.html

- ↑ Wall, Matt (16 July 2013). "What Are Neuromarketers Really Selling?". Slate.

- ↑ Etchells, Pete (5 December 2013). "Does neuromarketing live up to the hype?". The Guardian.

- ↑ Poole, Steven (September 6, 2012). "Your brain on pseudoscience: the rise of popular neurobollocks". New Statesman.

- ↑ Natasha Singer (13 November 2010). "Making Ads that Whisper to the Brain". The New York Times.

- ↑ Peter Osterlund (11 October 2013). "First they scan your brain. Then they set their price.". 60second Recap.

References

- Agarwal, S.; Dutta, T. (2015). "Neuromarketing and consumer neuroscience: current understanding and the way forward". Decision. 42 (4): 457–462. doi:10.1007/s40622-015-0113-1.

- Ait Hammou, K.; Galib, M.; Melloul, J. (2013). "The Contributions of Neuromarketing in Marketing Research". Jmr. 5 (4): 20. doi:10.5296/jmr.v5i4.4023.

- De Clerck, J. (2012). The importance of consumer behavior and preferences. i-SCOOP. Retrieved 30 March 2016, from http://www.i-scoop.eu/importance-consumer-behavior-preferences/

- Fisher, C.; Chin, L.; Klitzman, R. (2010). "Defining Neuromarketing: Practices and Professional Challenges". Harvard Review Of Psychiatry. 18 (4): 230–237. doi:10.3109/10673229.2010.496623.

- Glanert, M. (2012). Behavioral Targeting Pros and Cons - Behavioral Targeting Blog. Behavioral Targeting. Retrieved 31 March 2016, from http://behavioraltargeting.biz/behavioral-targeting-pros-and-cons/

- Kotler, P., Burton, S., Deans, K., Brown, L., & Armstrong, G. (2013). Marketing (9th ed., pp. 171). Australia: Pearson.

- Kelly, M. (2002). The Science of Shopping — Commercial Alert. Commercial Alert. Retrieved 30 March 2016, from http://www.commercialalert.org/news/archive/2002/12/the-science-of-shopping

- Morin, C (2011). "Neuromarketing: The New Science of Consumer Behavior". Soc. 48 (2): 131–135. doi:10.1007/s12115-010-9408-1.

- Shiv, B.; Yoon, C. (2012). "Integrating neurophysiological and psychological approaches: Towards an advancement of brand insights". Journal Of Consumer Psychology. 22 (1): 3–6. doi:10.1016/j.jcps.2012.01.003.

- Venkatraman, V.; Clithero, J.; Fitzsimons, G.; Huettel, S. (2012). "New scanner data for brand marketers: How neuroscience can help better understand differences in brand preferences". Journal Of Consumer Psychology. 22 (1): 143–153. doi:10.1016/j.jcps.2011.11.008.

- Mary Carmichael (November 2004). "Neuromarketing: Is It Coming to a Lab Near You?". PBS (Frontline, "The Persuaders"). Retrieved 2007-06-12.

- Media Maze: Neuromarketing, Part I

- http://edition.cnn.com/2010/TECH/innovation/10/05/neuro.marketing/index.html

Further reading

- Dawkins, Richard (1976). The Selfish Gene. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-286092-5.

- Lindström, Martin (2010). Buyology: Truth and Lies About Why We Buy. New York: Broadway Books. ISBN 9780385523899. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Renvoisé, Patrick; Morin, Christophe (2007). Neuromarketing: Understanding the "Buy Buttons" in Your Customer's Brain. Nashville: Thomas Nelson. ISBN 9780785226802.

- Zaltman, Gerald (2003). How Customers Think: Essential Insights into the Mind of the Markets. Boston: Harvard Business School Press. ISBN 9781578518265. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Żurawicki, Leon (2010). Neuromarketing: Exploring the Brain of the Consumer. New York: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 9789089651877.

External links

| Look up neuromarketing in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Dawkins' speech on the 30th anniversary of the publication of The Selfish Gene, Dawkins 2006

- "Evolution and Memes: The human brain as a selective imitation device": article by Susan Blackmore.

- Susan Blackmore: Memes and "temes", TED Talks February 2008

- Suomala J, Palokangas L, Leminen S, Westerlund M, Heinonen J, Numminen J (December 2012). "Neuromarketing: Understanding Customers' Subconscious Responses to Marketing". Technology Innovation Management Review: 12–21.