Neah Bay, Washington

| Neah Bay, Washington | |

|---|---|

| CDP | |

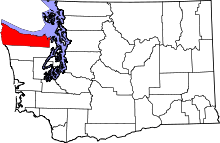

Location of Neah Bay, Washington | |

| Coordinates: 48°21′56″N 124°36′56″W / 48.36556°N 124.61556°WCoordinates: 48°21′56″N 124°36′56″W / 48.36556°N 124.61556°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Washington |

| County | Clallam |

| Area | |

| • Total | 2.4 sq mi (6.1 km2) |

| • Land | 2.4 sq mi (6.1 km2) |

| • Water | 0.0 sq mi (0.0 km2) |

| Elevation | 7 ft (2 m) |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Total | 865 |

| • Density | 335.8/sq mi (129.7/km2) |

| Time zone | Pacific (PST) (UTC-8) |

| • Summer (DST) | PDT (UTC-7) |

| ZIP code | 98357 |

| Area code | 360 |

| FIPS code | 53-48295[1] |

| GNIS feature ID | 1512497[2] |

Neah Bay is a census-designated place (CDP) on the Makah Reservation in Clallam County, Washington, United States. The population was 865 at the 2010 census. It is across from the Canada–US border with British Columbia.

Geography

Neah Bay is located at 48°21′56″N 124°36′56″W / 48.36556°N 124.61556°W (48.365436, −124.615672).[3]

According to the United States Census Bureau, the CDP has a total area of 2.4 square miles (6.1 km²), all of it land.

It is approximately one hundred and sixty miles northwest of Seattle.

Climate

Neah Bay has an oceanic climate (Cfb), common in the peninsula, but rare in its populated areas. The warmest month is August and the coldest month is December.[4]

Demographics

As of the census[1] of 2010, there were 865 people, 282 households, and 181 families residing in the CDP. The population density was 335.8 people per square mile (129.9/km²). There were 322 housing units at an average density of 136.2/sq mi (52.7/km²). The racial makeup of the CDP was 12.1% White, 0.2% African American, 77.1% Native American, .7% from other races, and 9.7% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 5.42% of the population.

There were 282 households out of which 37.6% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 36.2% were married couples living together, 17.7% had a female householder with no husband present, and 35.8% were non-families. 31.2% of all households were made up of individuals and 5.3% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.76 and the average family size was 3.38.

In the CDP the age distribution of the population shows 34.0% under the age of 18, 12.5% from 18 to 24, 26.7% from 25 to 44, 21.0% from 45 to 64, and 5.8% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 29 years. For every 100 females there were 123.7 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 128.8 males.

The median income for a household in the CDP was $21,635, and the median income for a family was $24,583. Males had a median income of $28,750 versus $27,917 for females. The per capita income for the CDP was $11,338. About 26.3% of families and 29.9% of the population were below the poverty line, including 32.6% of those under age 18 and 32.6% of those age 65 or over.

History

The name "Neah" refers to the Makah Chief Dee-ah, pronounced Neah in the Klallam language. The town is named for the water body Neah Bay, which acquired its name in the early 19th century. A number of names were used for the bay before it was established as Neah Bay. In August 1788 Captain Charles Duncan, a British trader, charted a bay at the location of Neah Bay, but did not give it a name. In 1790 Manuel Quimper took possession of the bay for Spain and named it "Bahía de Núñez Gaona" in honor of Alonso Núñez de Haro y Peralta, viceroy of New Spain. In 1792 Salvador Fidalgo began to build a Spanish fort on Neah Bay, but the project failed within the year. While Fidalgo was working on the fort George Vancouver charted but did not stop at the bay. American traders called Neah Bay "Poverty Cove". In 1841 the United States Exploring Expedition under Charles Wilkes mapped the region and named Neah Bay "Scarborough Harbour" in honor of Captain James Scarborough of the Hudson's Bay Company, who had provided assistance to the expedition. The Wilkes map contained the first use of the word "Neah", but for the bay's island, now called Waadah Island. The bay was first called Neah in 1847 by Captain Henry Kellett during his reorganization of the British Admiralty charts. Kellett spelled it "Neeah Bay".[5]

In 1929, the Neah Bay Dock Company, a subsidiary of the Puget Sound Navigation Company, owned a wharf and a hotel at Neah Bay.[6][7]

Economy

The local economy is sustained mostly by fishing and tourism. During the summer Neah Bay is a popular fishing area for sports fishermen. Any visitor to the Makah land must buy a recreational permit for US$10.[8] The permit is good for the calendar year.

Notable residents

- Edward Eugene Claplanhoo — former Chairman of the Makah Tribal Council, first Makah college graduate, established the Makah Museum and Fort Núñez Gaona–Diah Veterans Park.[9]

- Ruth Claplanhoo — Basket weaver, last native speaker of the Makah language.[10]

- Bob Greene — second-to-last surviving Makah veteran of World War II.[11]

- Ben Johnson, former Chairman and member of the Makah Tribal Council (1998–2000, 2001–2007)[12]

Fishing

Fishing for bottom fish, such as ling cod, kelp greenling, black rockfish (sea bass), china rockfish, yellow eye and canary rockfish, among others. Ling cod is good in spring and summer, while salmon fishing is good during summer runs. However — Neah Bay is mostly known for the best halibut fishing in the lower 48 states. The United States halibut season generally lasts a handful of days in May and June, ending when a seasonal quota is attained. When the United States halibut season is closed, some fishermen obtain Canadian fishing licenses and launch from Neah Bay, running approximately 10 miles (16 km) to the portion of Swiftsure Bank that lies in Canadian waters.

Popular spots for halibut include "The Garbage Dump", located just inside the Strait of Juan de Fuca, and Swiftsure Bank — a few miles out into the open ocean. Larger boats (including many of the commercial charter boats available) often travel 30 nautical miles (60 km) or more into the open ocean, to such places as Blue Dot and 72-Square.

Tourism

Neah Bay's significant attraction is the Makah Museum. It houses and interprets artifacts from a Makah village partly buried by a mudslide around 1750[13] at Ozette, providing a snapshot of pre-contact tribal life. The museum includes a replica longhouse, canoes, basketry and whaling and fishing gear. Many people visit Neah Bay to hike the Cape Trail or camp at Hobuck Beach. While camping, tourists spend time surfing and fishing.

Coast Guard

The United States Coast Guard maintains a base in Neah Bay on the Makah Indian reservation. The base is maintained for search and rescue, environmental protection and maritime law enforcement operations.

The Coast Guard cutter stationed in Cleveland, Ohio is named the Neah Bay (WTGB-105).

Response tug

In order to prevent disabled ships and barges from grounding and causing possible oil spills in the western Strait of Juan de Fuca or off the outer coast, the state funded an emergency response tug stationed at Neah Bay. It has saved 41 vessels since its introduction in 1999.[14]

Notes

- 1 2 "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- ↑ "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. 2007-10-25. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- ↑ "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. 2011-02-12. Retrieved 2011-04-23.

- ↑ Monthly Averages for Neah Bay, WA (98357)

- ↑ Meany, Edmond S. (1921). "Origin of Washington Geographic Names". The Pacific Northwest Quarterly. Washington University State Historical Society. X–XI: 279–280. Retrieved 2009-06-11.

- ↑ Kline and Bayless, Ferryboats – A Legend on Puget Sound, at page182.

- ↑ `

- ↑ http://www.makah.com/permits.htm

- ↑ Collins, Cary (2014-03-04). "Edward Claplanhoo's Lifetime of Service". Voice of the Valley. Archived from the original on 2014-04-16. Retrieved 2014-03-16.

- ↑ Barber, Mike (2002-08-21). "Basket weaver's legacy is woven into fabric of the Makah". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. Retrieved 2014-03-16.

- ↑ Ollikainen, Rob (2010-06-27). "Makah elder, fluent native speaker and World War II veteran, dies at 92". Peninsula Daily News. Retrieved 2010-07-06.

- ↑ Ollikainen, Rob (2014-04-03). "Former Makah tribal chairman dead at 74". Peninsula Daily News. Retrieved 2014-05-17.

- ↑ Prehistoric Cultures of North Americas. Crouthamel, American Indian Studies/Anthropology, Palomar College

- ↑ http://www.ecy.wa.gov/programs/spills/response_tug/tugresponsemainpage.htm; Washington State Department of Ecology; retrieved February 10, 2009

References

- Kline, Mary S., and Bayless, G.A., Ferryboats: A Legend on Puget Sound, Bayless Books, Seattle, Washington 1983 ISBN 0-914515-00-4

External links

- Neah Bay Halibut Fishing

- University of Washington Libraries Digital Collections – The Pacific Northwest Olympic Peninsula Community Museum A web-based museum showcasing aspects of the rich history and culture of Washington State's Olympic Peninsula communities. Features cultural exhibits, curriculum packets and a searchable archive of over 12,000 items that includes historical photographs, audio recordings, videos, maps, diaries, reports and other documents.

- Makah Cultural and Research Center Online Museum Exhibit History and culture of the Makah tribe.