Native American flute

|

Native American flute crafted by Chief Arthur Two-Crows, 1987 | |

| Woodwind instrument | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Native American style flute, courting flute, love flute, and many others |

| Classification | |

| Hornbostel–Sachs classification |

421.23 (MIMO revision[1]) (Flutes with internal duct formed by an internal baffle (natural node, block of resin) plus an external tied-on cover (cane, wood, hide)) |

| Playing range | |

| typically 1 – 1 1⁄3 octaves | |

| Related instruments | |

| More articles | |

| Flute circle, Eagle-bone whistle | |

| Indigenous music of North America |

|---|

| Music of indigenous tribes and peoples |

| Types of music |

| Instruments |

| Awards ceremonies and awards |

The Native American flute is a flute that is held in front of the player, has open finger holes, and has two chambers: one for collecting the breath of the player and a second chamber which creates sound. The player breathes into one end of the flute without the need for an embouchure. A block on the outside of the instrument directs the player's breath from the first chamber — called the slow air chamber — into the second chamber — called the sound chamber. The design of a sound hole at the proximal end of the sound chamber causes air from the player's breath to vibrate. This vibration causes a steady resonance of air pressure in the sound chamber that creates sound.[2]

Native American flutes comprise a wide range of designs, sizes, and variations — far more varied than most other classes of woodwind instruments.

Names

The instrument is known by many names.[3] Some of the reasons for the variety of names include: the varied uses of the instrument (e.g. courting), the wide dispersal of the instrument across language groups and geographic regions, legal statutes (see the Indian Arts And Crafts Act), and the Native American name controversy.

Alternative English-language names include: American Indian courting flute,[4] courting flute,[5] Grandfather's flute,[6] Indian flute,[7] love flute,[8] Native American courting flute,[9] Native American love flute,[10] Native American style flute (see the Indian Arts And Crafts Act), North American flute,[11] Plains flute,[12] and Plains Indian courting flute.[13]

Names in other languages include: Bavarian: Indianafletn, Cheyenne: tâhpeno, Chippewa: bĭbĭ'gwûn,[14] Dakota: ćotaŋke,[15] Dutch: Indiaans-Amerikaanse fluit, Esperanto: indiĝena amerikano fluto, French: Siyotanka, German: Indianerflöte, Hawaiian: Papa ʻAmelika ʻohe kani, Japanese: ネイティブアメリカンフルート, Kiowa: do'mba',[16] Korean: 아메리카 인디언 플루트, Lakota: Šiyótȟaŋka,[17] Lenape: achipiquon,[18] Polish: Flet indiański, Russian: Пимак, in the language of the Teguima: bícusirina,[19] and Zuni: Tchá-he-he-lon-ne (Sacred warbling flute).[20]

Naming Conventions

By convention, English-language uses of the name of the instrument are capitalized as "Native American flute". This is in keeping with the English-language capitalization of other musical instruments that use a cultural name, such as "French horn".[21]

The use of abbreviations (e.g. "NAF", "NASF") is discouraged.

The prevalent term for a person who plays Native American flutes is "flutist". This term predominates the term "flautist".[22] "Flute maker" is the predominant term for people who "craft" Native American flutes.

Organology

The instrument is classified in the 2011 revision of the Hornbostel–Sachs system by the MIMO Consortium as 421.23 — Flutes with internal duct formed by an internal baffle (natural node, block of resin) plus an external tied-on cover (cane, wood, hide).[1] This HS class also includes the Suling.

Although Native American flutes are played by directing air into one end, it is not strictly an end-blown flute, since the sound mechanism uses a fipple design using an external block that is fixed to the instrument.[2]

The use of open finger holes (finger holes that are played by the direct application and removal of fingers, as opposed to keys) classifies the Native American flute as a simple system flute.

History

There are many narratives about how different Indigenous peoples of the Americas invented the flute. In one narrative, woodpeckers pecked holes in hollow branches while searching for termites; when the wind blew along the holes, people nearby heard its music.[23] Another narrative from the Tucano culture describes Uakti, a creature with holes in his body that would produce sound when he ran or the wind blew through him.

It is not well known how the design of the Native American flute developed before 1823. Some of the influences may have been:

- Branches or stalks with holes drilled by insects that created sounds when the wind blew.[24]

- The design of the atlatl.[25]

- Clay instruments from Mesoamerica.[26][27]

- The Anasazi flute developed by Ancient Pueblo Peoples of Oasisamerica.

- Experience by Native Americans constructing organ pipes as early as 1524.[28][29]

- Recorders that came from Europe.

- Flutes of the Tohono O'odham culture (often referred to by the archaic exonym "Papago flutes"). Although crafted by a Native American people, these instruments are not strictly Native American flutes since they do not have an external block. In place of the block, the flue is formed by the player's finger on top of the sound mechanism. This style of flute may have been a precursor to, or one of the influences for, the Native American flute.[30][31]

- Flutes of the Akimel O'odham culture (often referred to by the archaic exonym "Pima flutes"). These flutes may have directly evolved from flutes of the Tohono O'odham culture, with the addition of a piece of cloth over the sound mechanism to serve as the external block.[32][33]

It is also possible that instruments were carried from other cultures during migrations.[34]

Flutes of the Mississippian culture have been found that appear to have the two-chambered design characteristic of Native American flutes. They were constructed of river cane. The earliest such flute is curated by the Museum Collections of the University of Arkansas, Fayetteville. It was recovered in about 1931 by Samuel C. Dellinger and more recently identified as a flute by James A. Rees, Jr. of the Arkansas Archeological Society. The artifact is known colloquially as "The Breckenridge Flute" and was conjectured to date in the range 750–1350 CE.[35][36] This conjecture proved to be accurate when, in 2013, a sample from the artifact yielded a date range of 1020–1160 CE (95% probability calibrated date range).[37]

The earliest extant Native American flute crafted of wood was collected by the Italian adventurer Giacomo Costantino Beltrami in 1823 on his search for the headwaters of the Mississippi River. It is now in the collection of the Museo Civico di Scienze Naturali in Bergamo, Italy.[38]

Construction

Components

The two ends of a Native American flute along the longitudinal axis are called the head end (the end closest to the player's mouth — also called the North end, proximal end, or top end) and the foot end (also called the bottom end, distal end, or South end).

The Native American flute has two air chambers: the slow air chamber (also called the SAC, compression chamber, mouth chamber, breath chamber, first chamber, passive air chamber, primary chamber, or wind chamber) and the sound chamber (also called the pipe body, resonating chamber, tone chamber, playing chamber, or variable tube). A plug (also called an internal wall, stopper, baffle, or partition) inside the instrument separates the slow air chamber from the sound chamber.

The block on the outside of the instrument is a separate part that can be removed. The block is also called the bird, the fetish, the saddle, or the totem. The block is tied by a strap onto the nest of the flute. The block moves air through a flue (also called the channel, furrow, focusing channel, throat, or windway) from the slow air chamber to the sound chamber. The block is often in the shape of a bird.[39]

Note that flutes of the Mi'kmaq culture are typically constructed from a separate block, but the block is permanently fixed to the body of the flute during construction (typically with glue). Even though these flutes do not have a movable block, they are generally considered to be Native American flutes.

The precise alignment and longitudinal position of the block is critical to getting the desired sound from the instrument. The longitudinal position also has a modest affect on the pitches produced by the flute, giving the player a range of roughly 10–40 cents of pitch adjustment.

The slow air chamber has a mouthpiece and breath hole for the player's breath. Air flows through the slow air chamber and up the ramp, through the exit hole, and into the flue.

The slow air chamber can serve as a secondary resonator, which can give some flutes a distinctive sound.

The sound chamber contains the sound hole, which creates the vibration of air that causes sound when the airflow reaches the splitting edge. The sound hole can also be called the whistle hole, the window, or the true sound hole ("TSH"). The splitting edge can also be called the cutting edge, the fipple edge, the labium, or the sound edge.

The sound chamber also has finger holes that allows the player to change the frequency of the vibrating air. Changing the frequency of the vibration changes the pitch of the sound produced.

The finger holes on a Native American flute are open, meaning that fingers of the player cover the finger hole (rather than metal levers or pads such as those on a clarinet). This use of open finger holes classifies the Native American flute as a simple system flute. Because of the use of open finger holes, the flutist must be able to reach all the finger holes on the instrument with their fingers, which can limit the size of the largest flute (and lowest pitched flute) that a given flutist can play. The finger holes can also be called the note holes, the playing holes, the tone holes, or the stops.

The foot end of the flute can have direction holes. These holes affect the pitch of the flute when all the finger holes are covered. The direction holes also relate to (and derive their name from) the Four Directions of East, South, West, and North found in many Native American stories. The direction holes can also be called the tuning holes or wind holes.

In addition to the Components of the Native American flute diagram shown above with English-language labels, diagrams are available with labels in Cherokee, Dutch, Esperanto, French, German, Japanese, Korean, Polish, Russian, and Spanish.

Spacer Plate

An alternate design for the sound mechanism uses a spacer plate to create the flue. The spacer plate sits between the nest area on the body of the flute and the removable block. The spacer player is typically held in place by the same strap that holds the block on the instrument. The splitting edge can also be incorporated into the design of the spacer plate.

The spacer plate is often constructed of metal, but spacer plates have been constructed of wood, bark, and ceramic.

When positioning and securing the removable block with the strap, the use of a spacer plate provides and additional degree of control over the sound and tuning of the flute. However, it also adds a degree of complexity when performing the task of securing both the block and the spacer plate.

Plains Style vs. Woodlands Style Native American flutes

Various sources describe attributes of Native American flute that are termed "Plains style" and "Woodlands style". However, there's no general consensus among the various sources about what these styles mean.[40] According to various sources the distinction is based on:

- whether the flute uses a spacer plate to create the flue of the instrument,[41]

- whether the flue is in the body of the flute or the bottom of the block,[42]

- the sharpness of the angle of the splitting edge,

- whether the finger holes are burned or bored into the body of the flute,

- the design of the mouthpiece (blunt and placed against the lips vs. designed to go between the lips),

- the timbre of the sound of the flute, or

- details of the fingering for the primary scale.

Branch flutes

While many contemporary Native American flutes are crafted from milled lumber, some flutes are crafted from a branch of a tree. The construction techniques vary widely, but some makers of branch flutes will attempt to split the branch down a centerline, hollow out the inside, and then mate the halves back together for the completed flute.[43]

Double and Multiple flutes

A double Native American flute is a type of double flute. It has two sound chambers that can be played simultaneously. The two chambers could have the same length or be different lengths.

The secondary sound chamber can hold a fixed pitch, in which case the term "drone flute" is sometimes used. The fixed pitch could match the fingering of the main sound chamber with all the finger holes covered, or it could match some other pitch on the main sound chamber. Alternately, various configurations of finger holes on the two sound chambers can be used, in which case terms such as "harmony flute" or "harmonic flute" are sometimes used.

Extending the concept, Native American flutes with three or more chambers have been crafted. The general term "multiple flute" is sometimes used for these designs.

Dimensions

Some Native American flutes constructed by traditional techniques were crafted using measurements of the body. The length of the flute was the distance from inside of the elbow to tip of the index finger. The length of the slow air chamber was the width of the fist. The distance between the sound hole and first finger hole was the width of the fist. The distance between finger holes would be the width of a thumb. The distance from the last finger hole to the end of the flute was the width of the fist.[41][44]

Flute makers currently use many methods to design the dimensions of their flutes. This is very important for the location of the finger holes, since they control the pitch of the different notes of the instrument. Flute makers may use calculators to design their instruments,[45] or use dimensions provided by other flute makers.[46]

Materials

Native American flutes were traditionally crafted of a wide range of materials, including wood (cedar, juniper, walnut, cherry, and redwood are common), Bamboo, and river cane. Flute makers from indigenous cultures would often use anything that could be converted or made into a long hollow barrel, such as old gun barrels.[41]

Poetic imagery regarding the covenant between flute maker and player was provided by Kevin Locke in the Songkeepers video:[47]

The flute maker has to take that cedar, split it open, and remove that beautiful, straight-grained, aromatic, sweet, soft, deep-red heart of the cedar. And then they will re-attach both halves and put the holes in. And so the covenant or reciprocal agreement is that the flute player will instill the heart back into the wood — put their heart back in there.

Contemporary Native American flutes continue to use these materials, as well as plastics, ceramic, glass, and more exotic hardwoods such as Ebony, Padauk, and Teak.

Various materials are chosen for their aromatic qualities, workability, strength and weight, and compatibility with construction materials such as glue and various finishes. Although little objective research has been undertaken, there are many subjective opinions expressed by flute makers and players about the sound qualities associated with the various materials used in Native American flutes.

Physiology

Heart Rate Variability

One study that surveyed the physiological effects of playing Native American flutes found a significant positive effect on heart rate variability, a metric that is indicative of resilience to stress.[48]

Ergonomics

Contemporary Native American flutes can take ergonomic considerations into account, even to the point of custom flute designs for individual flute players. However, the ergonomic issues related to these instruments are not well-studied and ergonomic designs are not widespread; one study reported that 47–64% of players reported physical discomfort at least some of the time, while over 10% of players reported moderate discomfort on an average basis.[49]

Sound and Tuning

|

Native American flute (six holes).

Performed on a 1987 flute crafted by Chief Arthur Two-crows. |

| Problems playing this file? See media help. | |

|

Native-American-style flute (five holes) G.

Performed on a 2001 flute crafted by Rick Heller. |

| Problems playing this file? See media help. | |

The predominant scale for Native American flutes crafted since the mid-1980s (often called "contemporary Native American flutes") is the pentatonic minor scale. The notes of the primary scale comprise the root, minor third, perfect fourth, perfect fifth, minor seventh, and the octave.

Recently some flute makers have begun experimenting with different scales, giving players new melodic options.

The pitch standard used by many Native American flutes before the mid-1980s was arbitrary. However, contemporary Native American flutes are often tuned to a concert pitch standard so that they can be easily played with other instruments.

The root keys of contemporary Native American flutes span a range of about three and a half octaves, from C2 to A5.[50]

Early recordings of Native American flutes are available from several sources.[51]

Fingering

Native American flutes typically have either five or six finger holes, but any particular instrument may have from zero to seven finger holes. The instrument may include a finger hole covered by the thumb.

The fingerings for various pitches are not standardized across all Native American flutes. However, many contemporary Native American flutes will play the primary scale using the fingering shown in the adjacent diagram.

While the pentatonic minor scale is the primary scale on most contemporary Native American flutes, many flutes can play notes of the chromatic scale using cross-fingerings.[52]

Tuning

Native American flutes are available in a wide variety of keys and musical temperaments — far more than typically available for other woodwind instruments. Instruments tuned to equal temperament are typically available in all keys within the range of the instrument. Instruments are also crafted in other musical temperaments, such as just intonation, and pitch standards, such as A4=432 Hz.

The Warble

A distinctive sound of some Native American flutes, particularly traditional flutes, is called the "warble" (or "warbling"). The warble sounds as if the flute is vacillating back and forth between distinct pitches. However, it is actually the sound of different harmonic components of same sound coming into dominance at different times.[53]

John W. Coltman, in a detailed analysis of flute acoustics, describes two types of warbles in Native American flutes: One "of the order of 20 Hz" caused by a "nonlinearity in the jet current", and a second type "in which amplitude modulation occurs in all partials but with different phases". The first type is analyzed by Coltman in a controlled setting, but he concluded that analysis of the second type of warble "is yet to be explained".[54]

The warble can be approximated by use of vibrato techniques. The phase shift that occurs between different harmonics can be observed on a spectrograph of the sound of a warbling flute.[53]

Written Music

Written music for the Native American flutes is often in the key of F-sharp minor, although some music is scored in other keys. However, the convention for music written in F-sharp minor is to use a key signature of four sharps. This convention is known as "Nakai tablature". Note that the use of finger diagrams below the notes that is part a high percentage of written music for the Native American flutes is not necessarily part of Nakai tablature.

The use of a standard key signature for written music that can be used across Native American flutes in a variety of keys classifies the instrument as a transposing instrument.

Music

Extensive ethnographic recordings were made by early anthropologists such as Alice Cunningham Fletcher, Franz Boas, Frank Speck, Frances Densmore, and Francis La Flesche. A small portion of these recordings included Native American flute playing. One catalog lists 110 ethnographic recordings made prior to 1930.[55]

These recordings capture traditional styles of playing the instrument in a sampling of indigenous cultures and settings in which the instrument was used.

However, the legal and ethical issues surrounding access to these early recordings are complex. Because of incidents of misappropriation of ethnographic materials recorded within their territories, Indigenous communities today claim a say over whether, how and on what terms elements of their intangible cultural heritage are studied, recorded, re-used and represented by researchers, museums, commercial interests and others.[56]

During the period 1930–1960, few people were playing the Native American flute. However, a few recordings of flute playing during this period are commercially available. One such recording is by Belo Cozad, a Kiowa flute player who made recordings for the U. S. Library of Congress in 1941.[57]

Revival

During the late 1960s, the United States saw a roots revival of the Native American flute, with a new wave of flutists and artisans such as Doc Tate Nevaquaya, John Rainer, Jr., Sky Walkinstik Man Alone, and Carl Running Deer.

The music of R. Carlos Nakai became popular in the 1980s, in particular with the release of the album "Canyon Trilogy" in 1989. His music was representative of a shift in style from a traditional approach to playing the instrument to incorporate the New-age genre.[58] In 1998, Canyon Trilogy was the first Native American music album certified as a Gold Record by the Recording Industry Association of America. Canyon Trilogy was certified as a Platinum Record on July 8, 2014.[59]

Mary Youngblood won two Grammy Awards in the Native American Music category for her Native American flute music in 2002 and 2006. She remains the only Native American flutist to be distinguished in this way, as the National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences retired the category in 2011.

Today, Native American flutes are being played and recognized by many different peoples and cultures around the world.

Community Music

The Native American flute has inspired hundreds of informal community music groups which meet periodically to play music and further their interest in the instrument. These groups are known as flute circles.[60]

Several national organizations have formed to provide support to these local flute circles:

- WFS — World Flute Society (U.S.A.)

- FTF — FluteTree Foundation (U.S.A.) (formerly RNAFF, Renaissance of the North American Flute Foundation)[61]

- JIFCA — Japan Indian Flute Circle Association (日本インディアンフルートサークル協会) (Japan)

Statistics

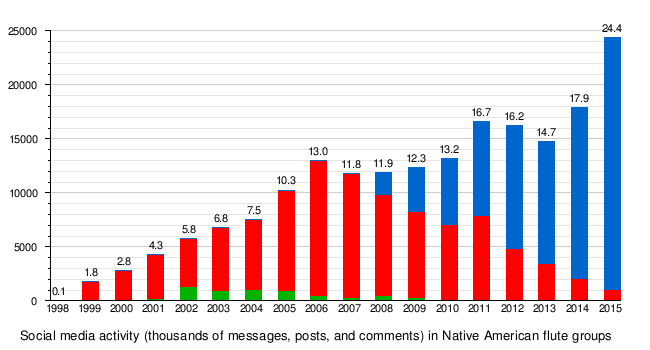

The chart below depicts the activity in publicly accessible social media groups specific to the Native American flute. Three domains are shown:

- Green: Number of yearly messages distributed through the "Montana Listserver", a LISTSERV that provided an Electronic mailing list service from June 2, 1998 through June 3, 2013, as determined from an archive of activity. However, the count of message prior to October 15, 2001 are not available.

- Red: Number of yearly messages on the 12 most active Yahoo! Groups specific to Native American flute, as reported by Yahoo!.

- Blue: Number of yearly posts and comments on the 8 most active public groups on Facebook, as reported by Sociograph.io.

The chart shows an average 39% annual growth rate in aggregate activity from 1998 (the inception of Yahoo! Groups) through 2015. However, note that these statistics do not take into account the change over this period in accessibility to the Internet, use of social media vs. private messages, the use of closed and secret groups on Facebook, and other confounding factors. Despite these limitations, the chart does indicate a substantial rate of growth in activity and interest.

For additional statistics, see the flute circle article.

Popular Appeal

The Native American flute has gained popularity among flute players, in large part because of its simplicity. According to a thesis by Mary Jane Jones:[62]:56–57

The flute's cathartic appeal probably lies in its simplicity. In their quest to build instruments that could play several chromatic octaves with perfect intonation, Europeans produced mechanically complex instruments that require a great deal of technical skill on the part of the musician. Until a high level of competence is achieved, pouring out one‘s innermost feelings during a performance is extremely difficult. The ability to play musically and emotionally is subject to the musician‘s technical ability. As most music teachers will attest, many beginners take so long to master the necessary skills and are so focused on the technical aspects of their instruments that they must eventually be taught how to play with feeling. Struggling with the demands of their instruments over time causes them to lose the emotional connection to music that they may have felt when singing as young children. Since beginners can play melodies on the Native American flute with ease, it is possible for them to play expressively from the outset. As flute players become better acquainted with their instruments, their improvisations tend to become longer, have more complex melodies and forms, and contain more embellishments. However, the ability to express emotion through improvisation on the flute seems as easy for the beginner as it is for the advanced student.

Flutists and composers

Notable and award winning Native American flutists include: R. Carlos Nakai, Charles Littleleaf, Joseph Firecrow, Arvel Bird, Joseph RiverWind, David R. Maracle, John Two-Hawks, Kevin Locke, Aaron White, Robert Mirabal,

A few classical composers have written for the Native American flute, including James DeMars, David Yeagley, Frank Martinez, Brent Michael Davids, Philip Glass, Jerod Impichchaachaaha' Tate.

Legal Issues

1990 Indian Arts And Crafts Act

The 1990 Indian Arts And Crafts Act of the United States criminalized deceptive product-labeling of goods that are ostensibly made by Native Americans. In the United States, wrongfully claiming that an artifact is crafted by "an Indian" is a felony offense. The US Department of the Interior explicitly states on its informational website about the Act that, "Under the Act, an Indian is defined as a member of any federally or State recognized Indian Tribe, or an individual certified as an Indian artisan by an Indian Tribe."[63]

Based on this statue, only a flute fashioned by a person who qualifies as an Indian under the terms of the statue can legally be sold as a "Native American flute" or "American Indian flute". However, although there is no official public ruling on alternative terms that are acceptable, it is general practice that any manufacturer or vendor may legally label their work-product by other terms such as "Native American style flute" or "North American flute". Labels such as "in the style of", or "in the spirit of", or "replica" may also be used.[64]

However, while the Act applies to offering handmade arts and crafts offered to the public for sale, it does not apply to the use of Native American flutes in situations such as performance, workshops, or recording.[64]

Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918

The Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918 makes it unlawful (without a waiver) to use materials from species protected by the Act in a musical instrument.[65] This statute applies to the eagle-bone whistle, examples of which might or might not be classified as a Native American flute depending on the particulars of their construction.

Documentaries

- Songkeepers (1999, 48 min.). Directed by Bob Hercules. Produced by Dan King. Lake Forest, Illinois: America's Flute Productions. Five distinguished traditional flute artists - Tom Mauchahty-Ware, Sonny Nevaquaya, R. Carlos Nakai, Hawk Littlejohn, Kevin Locke – talk about their instrument and their songs and the role of the flute and its music in their tribes.[66]

- Journey to Zion (2008, 44 min.). A documentary by Tim Romero. Santa Maria, California: Solutions Plus. An inspirational documentary about Native flute enthusiasts attending the Zion Canyon Art & Flute Festival located in Springdale, Utah, the gateway to Zion National Park.[67]

See also

References

- 1 2 MIMO Consortium (8 July 2011). Revision of the Hornbostel–Sachs Classification of Musical Instruments by the MIMO Consortium (PDF).

- 1 2 Clint Goss (2016). "FAQ for the Native American Flute". Flutopedia. Retrieved 2016-02-16.

- ↑ Clint Goss (2016). "Names of the Native American flute". Flutopedia. Retrieved 2016-02-16.

- ↑ Edward Wapp, Jr. (1984). "The American Indian Courting Flute: Revitalization and Change". Sharing a Heritage: American Indian Arts, edited by Charlotte Heth and Michael Swarm. Contemporary American Indian Issues Series, Number 5. Los Angeles: American Indian Studies Center, UCLA: 49–60.

- ↑ George Catlin (1841). Letters and Notes on the Manners, Customs, and Condition of the North American Indians. Volume 2. the author.

- ↑ Lew Paxton Price (1995). Creating and Using Grandfather's Flute. Love Flutes Series. 2. ISBN 0-917578-11-2.

- ↑ Isaac Weld, Jr. (1800). Travels Through the States of North America and the Provinces of Upper and Lower Canada, During the Years 1795, 1796, and 1797 (Fourth ed.). Piccadilly, London: John Stockdale.

- ↑ Mary H. Eastman (1853). The Romance of Indian Life — With other tales, Selections from the Iris, An Illuminated Souvenir. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Lippincott, Grambo & Co.

- ↑ Butch Hall (1997). Favorite Hymns — In Tablature for the Native American Courting Flute. Butch Hall Flutes.

- ↑ Lew Paxton Price (1994). Creating and Using the Native American Love Flute. Love Flutes Series. 1. P.O. Box 88, Garden Valley, CA 95633: L. P. Price. ISBN 0-917578-09-0.

- ↑ Lew Paxton Price (1990). Native North American Flutes. ISBN 0-917578-07-4.

- ↑ Richard W. Payne (1988). "The Plains Flutes". The Flutist Quarterly. 13 (4): 11–14.

- ↑ Richard Keeling (1997). North American Indian Music: A Guide to Published Sources and Selected Recordings. Garland Library of Music Ethnology, 5; Garland Reference Library of the Humanities, 1440. New York: Garland Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8153-0232-2.

- ↑ Frances Densmore (1913). Chippewa Music II. Smithsonian Institution, Bureau of American Ethnology. 53. Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office.

- ↑ Stephen Return Riggs (1893). Dakota Grammar, Texts, and Ethnography. Contributions to North American Ethnology, Volume 9. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office.

- ↑ James Mooney (1898). "Calendar History of the Kiowa". Seventeenth Annual Report of the Bureau of American Ethnology to the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, 1895-96. Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office (part 1): 129–468.

- ↑ Frances Densmore (1918). Teton Sioux Music and Culture. Smithsonian Institution, Bureau of American Ethnology. 61. Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office.

- ↑ Kevin Doyle (October 2000). Lenape Dictionary.

- ↑ Hubert Howe Bancroft (1875). The Native Races of the Pacific States of North America. Volume 3 — Myths and Languages. New York: D. Appleton and Company.

- ↑ James Stevenson (1884). "Illustrated Catalogue of the Collections Obtained from the Pueblos of Zuñi, New Mexico, and Wolpi, Arizona, in 1881". Third Annual Report of the Bureau of American Ethnology to the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, 1881-'82. Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office: 511–594.

- ↑ University of Chicago (2003). The Chicago Manual of Style (15th ed.). Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press. pp. 366–377. ISBN 0-226-10403-6.

- ↑ based on searches on the Google search engine performed on February 26, 2016 for "Native American flutist" (about 23,800 results) and "Native American flautist" (about 3,090 results).

- ↑ Clint Goss (2010). "Legends and Myths of the Native American Flute". Flutopedia. Retrieved 2010-12-13.

- ↑ Clint Goss (2016). "Proto-Flutes and Yucca Stalks". Flutopedia. Retrieved 2016-02-23.

- ↑ Robert L. Hall (1997). An Archaeology of the Soul: North American Indian Belief and Ritual. University of Illinois Press. pp. 114–120. ISBN 978-0-252-06602-3.

- ↑ Susan Rawcliffe (December 1992). "Complex Acoustics in Pre-Columbian Flute Systems". Experimental Musical Instruments. 8 (2).

- ↑ Susan Rawcliffe (2007). "Eight West Mexican Flutes in the Fowler Museum". World of Music. Bamberg, Germany: Journal of the Department of Ethnomusicology, Otto-Friedrich University. 49 (2): 45–65. JSTOR 41699764.

- ↑ Clint Goss (2016). "Organ Pipes and the Native American Flute". Flutopedia. Retrieved 2016-02-26.

- ↑ Richard Kassel (2006). The Organ: An Encyclopedia. Volume 3 of The Encyclopedia of Keyboard Instruments. Psychology Press. p. 349. ISBN 978-0-415-94174-7.

- ↑ Richard W. Payne (1989). "Indian Flutes of the Southwest". Journal of the American Musical Instrument Society. 15: 5–31.

- ↑ Clint Goss (2016). "Indigenous North American Flutes - Papago flutes". Flutopedia. Retrieved 2016-02-26.

- 1 2 Frank Russell (1908). "The Pima Indians". Twenty-sixth Annual Report of the Bureau of American Ethnology to the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, 1904-1905. Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office: 166.

- ↑ Clint Goss (2016). "Indigenous North American Flutes - Pima flutes". Flutopedia. Retrieved 2016-02-26.

- ↑ Clint Goss (2010). "A Brief History of the Native American Flute". Flutopedia. Retrieved 2010-12-13.

- ↑ Clint Goss (2012). "The Breckenridge Flute". Flutopedia. Retrieved 2012-01-05.

- ↑ James A. Rees, Jr. (July–August 2011). "Musical Instruments of the Prehistoric Ozarks". Field Notes Newsletter of the Arkansas Archaeological Society (361): 3–9.

- ↑ James A. Rees; Jr. (July–August 2013). "The Breckenridge Flute Dated with ARF Grant". Field Notes Newsletter of the Arkansas Archaeological Society. 373: 11–12.

- ↑ Clint Goss (2010). "The Beltrami Flute". Flutopedia. Retrieved 2010-12-13.

- ↑ Robert Gatliff (2005). "Anatomy of the Plains Flute". FluteTree. Retrieved 2016-02-18.

- ↑ Clint Goss (2010). "Plains Style and Woodlands Style Native American Flutes". Flutopedia. Retrieved 2010-12-13.

- 1 2 3 Anatomy of the Plains Flute, Flutetree.com

- ↑ Richard W. Payne (1999). The Native American Plains Flute. Oklahoma City, Oklahoma: Toubat Trails Publishing Co.

- ↑ Clint Goss (2016). "Branch Flutes". Retrieved 2016-03-23.

- ↑ Clint Goss (2015). "Native American Flute Finger Hole Placement". Flutopedia. Retrieved 2015-12-06.

- ↑ Clint Goss (2016). "NAFlutomat — Native American Flute Design Tool". Flutopedia. Retrieved 2016-02-21.

- ↑ Clint Goss (2016). "Flute Crafting Dimensions". Flutopedia. Retrieved 2016-02-21.

- ↑ Rita Coolidge (1999). Songkeepers: A Saga of Five Native Americans Told Through the Sound of the Flute. Lake Forest, Illinois: America's Flute Productions.

- ↑ Eric B. Miller; Clinton F. Goss (January 2014). "An Exploration of Physiological Responses to the Native American Flute" (PDF). arXiv:1401.6004

. Retrieved 25 Jan 2014.

. Retrieved 25 Jan 2014.

- ↑ Clinton F. Goss (January 2015). "Native American Flute Ergonomics" (PDF). arXiv:1501.00910

. Retrieved 7 Jan 2015.

. Retrieved 7 Jan 2015.

- ↑ Clint Goss (2010). "Keys of Native American Flutes". Flutopedia. Retrieved 2010-12-13.

- ↑ Clint Goss (2010). "Early Native American flute Recording Discography". Flutopedia. Retrieved 2010-12-13.

- ↑ Clint Goss (2010). "Native American Flute Fingering Charts". Flutopedia. Retrieved 2010-12-13.

- 1 2 Clint Goss; Barry Higgins (2013). "The Warble". Flutopedia. Retrieved 2013-03-06.

- ↑ J. W. Coltman (October 2006). "Jet Offset, Harmonic Content, and Warble in the Flute". Journal of the Acoustic Society of America. 120 (4): 2312–2319. doi:10.1121/1.2266562. PMID 17069326.

- ↑ Clint Goss (2016). "Ethnographic Flute Recordings of North America — Organized Chronologically". Flutopedia. Retrieved 2016-03-08.

- ↑ Martin Skrydstrup (June 2009). Towards Intellectual Property Guidelines and Best Practices for Recording and Digitizing Intangible Cultural Heritage — A Survey of Codes, Conduct and Challenges in North America. World Intellectual Property Organization.

- ↑ Stephen Wade (1997). Library of Congress: A Treasury of Library of Congress Field Recordings. Rounder Records.

- ↑ Paula Conlon (2002). "The Native American Flute: Convergence and Collaboration as Exemplified by R. Carlos Nakai". The World of Music. 44 (1): 61–74. JSTOR 41699400.

- ↑ "RIAA". 2016. Retrieved 2016-02-22.

- ↑ World Flute Society (2016). "Flute Circles, Clubs, and Groups". WFS. Retrieved 2016-02-18.

- ↑ Wolf, Gary (March 25, 2016). "Arizona Corporation Commission File Number 20799170". Retrieved March 25, 2016.

- ↑ Mary Jane Jones (August 2010). Revival and Community: The History and Practices of a Native American Flute Circle (M.A.). Kent State University, College of the Arts / School of Music.

- ↑ "The Indian Arts and Crafts Act of 1990." US Department of the Interior, Indian Arts and Crafts Board. Retrieved 24 May 2009.

- 1 2 Kathleen Joyce-Grendahl (2010). "Indian Arts and Crafts Amendment of 2010". Voice of the Wind. Suffolk, Virginia: International Native American Flute Association. 2010 (4): 28.

- ↑ "Migratory Bird Management Information: List of Protected Birds (10.13) Questions and Answers" (PDF). US Fish & Wildlife Service. Retrieved 7 August 2015.

- ↑ Joyce-Grendahl, Kathleen. "Songkeepers: A Video Review". worldflutes.org. Suffolk: International Native American Flute Association. Archived from the original on 2010-08-12. Retrieved 2010-08-13. And: National Museum of the American Indian. Archived March 3, 2006, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Journey to Zion documentary website". Archived March 2, 2012, at the Wayback Machine.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Native American flutes. |

- Flutopedia Flutopedia — an Encyclopedia for the Native American Flute.

- Native American flute music sheet

- FluteTree Foundation

- World Flute Society