Nationalisms and regionalisms of Spain

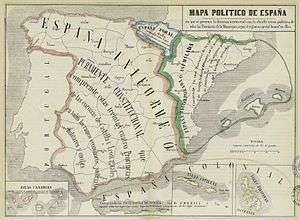

The modern country of Spain was formed in the wake of the expansion of the Christian states in northern Spain, a process known as the Reconquista. The Reconquista spanned approximately 770 years between the battle of Covadonga c. 720 CE and the fall of Granada in 1492.

Several independent Christian kingdoms and mostly independent political entities (Asturias, León, Galicia, Castile, Navarre, Aragon, Catalonia) were formed by their own inhabitants' efforts under aristocratic leadership, coexisting with the Muslim Iberian states and having their own identities and borders.

Eventually, the kingdoms of Castile and Aragon eclipsed the others in power and size through conquest and dynastic inheritance, their Crowns ultimately merging in 1469 with the marriage of the Catholic Monarchs. After this, the Muslim kingdom of Granada was conquered in 1492, and Navarre invaded and forced into the union in 1512, through a combination of conquest and collaboration of the local elites.

Portugal, formerly part of León, gained independence in 1128 after a split in the Royal inheritance of the daughters of Alfonso VI and remained independent throughout the reconquista process.

For a short time starting with Philip II of the House of Habsburg, Portugal was united with all the other realms under the same Head of State, in the Iberian Union. However the Portuguese revolted as the Dutch provinces and other Habsburg dominions and became officially independent again from their Sovereigns in 1640.

These kingdoms sometimes collaborated when they fought against Muslim Spain and sometimes allied themselves with the Muslims against rival Christian neighbors. The common non-Christian enemy has been usually considered the single crucial catalyst for the union of the different Christian realms. However, it was effective only for permanently reconquered territories. The unifications that came later were and are a whole different subject, as some of them happened long after the departure of the last Muslim rulers.[1]

All these different kingdoms were ruled together, or separately in personal union, but maintained their particular ethnic differences, regardless of similarities through common origins or borrowed customs.

Since the reign of Philip V, there has been a process of uniformization by the central authorities.[2]

This uniformization has been resisted by some of the local elites, who have their own national consciousness based on traditional, historical, linguistic and cultural attributes.

Some Kingdoms, like Navarre and the Lordships of the Basque Country, maintained constitutions based on their historical rights and laws, while other Kingdoms revolted against this process of centralism demanding a return of their derogated laws as well as better living conditions (Revolt of the Comuneros, Revolt of the Brotherhoods, Catalan Revolt). Nationalistic movements with significant support appear by the end of the 19th century, coinciding with the loss of the last parts of the Spanish Empire, the abolition of privileges, and continued high mercantile traditions with later industrial developments of some regions in comparison to others.

Following the Spanish Civil War, the Francoist imposition of Spanish as the only official language, and the persecution of all remaining historical languages and identities, had the effect of putting the constituent nations' survival in danger, leading to many powerful expressions of nationalism.[3]

Since the beginning of the Spanish transition to democracy after the dictatorship of Francisco Franco, there have been many movements for more autonomy in certain regions of the country, advocating full independence in some cases, and an autonomous "community" in others. It is a controversial topic in Spain, and references to it can be found almost every day in the press, especially in the Basque Country and Catalonia.

The currently two most voted parties in Spain have different views on the subject. The People’s Party supports a more centralized Spain, with a unitary market, and usually does not support movements advocating greater regional autonomy. The Spanish Socialist Workers' Party supports a federal state with greater autonomy for the regions, but is opposed to total independence for any region.

The structure of this article is determined by the amount of popular support for the individual movements, so that even though there are political parties demanding independence from Spain for Castile, Cantabria, Valencia, Andalusia and Murcia, these parties hardly get any votes, and thus do not represent popular sentiment in their regions (percentages of nationalist and regionalist votes are given in parentheses according to figures of the elections held at municipality level in May 2007).

Note that the only two autonomous communities not mentioned in this article are Madrid (capital of the State, traditionally part of Castilla-la Nueva [New Castile in English], most of its population identifies itself primarily just with Spain).

Nationalism

Andalusia

- (Nationalism-Regionalism: 2.51% PA). The Unitarian Candidacy of Workers has one deputy in the Andalusian parliament, but he was elected in the lists of the United Left (Andalusian parliamentary election, 2012)

Andalusia first Statute of Autonomy could not be enacted during the Republican government because of the Spanish Civil War, and, although it is not considered a historical community in the literal sense, it expanded the autonomy after a referendum (1981).

Also, the Andalusians speak varieties of southern Spanish that collectively are perceived in Spain as being the most different from standard Spanish. However, there is no marked dialectal discontinuity with neighbouring regions, Extremaduran Spanish is quite close to western Andalusian and Murcian is also not very different from eastern varieties of Andalusian. In its extreme form the speech may be difficult to understand by those who are not familiar with Southern Spanish. Andalusian Spanish is traditionally considered a dialect, even though it has a lot of internal variation.

Its old Statute of Autonomy defines this region as a nationality. In the new Statute of Autonomy, approved in referendum on February 18, 2007, Andalusia is defined as a national entity in the preamble ('Andalusian manifesto of Cordoba described Andalusia as a national reality in 1919...') and as a historic nationality in its first section. According to a poll [4] 18.1% supported declaring Andalusia a nation in the new statute as a nation, while 60.7% of Andalusians did not agree with it.

Andalusian nationalism has a strong presence in the trade union movement. In fact, the nationalist Sindicato Andaluz de Trabajadores (SAT) has 25.000 members and a very strong presence in the rural areas.

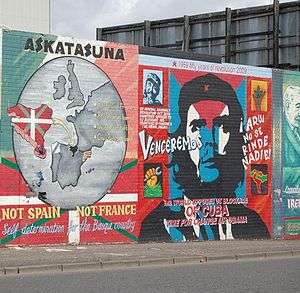

Basque Country

- (~59.64% PNV+EH Bildu; Basque parliamentary election, 2012)

- (30.08% Geroa Bai+EH Bildu;[5] Navarrese parliamentary election, 2015)

Basque nationalism runs the range from full independence to further devolution to the Basque government.

For instance, the Basque Nationalist Party (PNV) regularly wins elections at municipal, regional or Spanish levels in the Basque Country, but the fact that it achieves a mere plurality and that electors of PNV do not unanimously support (full) independence, counters the belief that independence is generally supported by the Basque population. In the 2011 Spanish elections the left-wing abertzale coalition Amaiur obtained 6 seats in the Spanish parliament and 24.12% of votes in the Basque Country and one seat and the 14.86% of votes in Navarre. The Basque Nationalist Party obtained 5 seats and the 27.42% of votes. The navarrese coalition Geroa Bai obtained one seat and the 12.84% of votes in Navarre. Basque trade unions are also very strong, the Basque Workers' Solidarity union has 109,318 members and is the most important union in the Basque Country, while LAB, linked with the abertzale left is the third trade union and has 40,000 members.[6][7]

According to recent studies (see Euskobarómetro , ), a plurality (38%) of the population in the Basque Country autonomous community would vote YES, 31% NO, 13% not voting in a hypothetical independence referendum, and 19% did not answer (Voter turnout would be 68-69%, when taking that figure as the whole 100%, 55% of the voters would answer YES and 45% NO). Different results appear when the options are independence, further devolution or the current status. The option for a restoration of centralization is barely recorded. According to a 2012 poll made by the CIS, 49.8% of the Basques and 43.7% of Navarrese want more autonomy. Only 3.1% of Basques and 7.3% of Navarrese want less autonomy.

The nationalists consider Navarre and the French Basque Country as part of the same nation, the Basque Country. In the current Basque Statute of Autonomy it is stated that Navarre has the legal right to belong to the autonomous community of the Basque Country, and the Spanish Constitution has a transitory provision allowing it to join at any time, but Navarrese politicians chose not to enter the agreement and became a Foral Community instead.

The Statute of Autonomy of the Basque Country defines this region as a nationality.

In 2003, Lehendakari Juan José Ibarretxe proposed a plan that would have changed the current status of the Basque Country as an autonomous community to a "status of free association" (see Associated state and Free State). It was approved 39-35 by the Basque Parliament, but the Spanish Congress of Deputies rejected it 29-313 in 2005, thus halting the progress of the reform.

The then President of the Spanish Government, José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero, stated that he will support any reform to the Statute of Autonomy which is supported by 2/3 of the Basque Parliament (a verbal condition not legally written anywhere, for the only condition needed for a statute to be approve is the half of the total plus one votes in the Basque Parliament).

On 29 September 2007 Juan José Ibarretxe declared that an autonomic referendum or a popular poll about the will of the population of the Basque Country on independence would be held on 25 October 2008, but it was declared illegal and forbidden by the Constitutional Court.

Catalonia

- Moderate Catalanism / federalism (PSC-PSOE, ICV) = 34.72% of vote General elections 2011 (50.31% in 2008)

- Independentist/sovereignty Catalanism (ERC, CiU) = 36.41% of vote General elections 2011 (28.76% in 2008)[8]

Historically catalanism has supported a federal system that includes a Catalan nation within Spain. Not all catalanist parties openly call for an independent state; the ones that do it are Republican Left of Catalonia (ERC), Catalan Solidarity for Independence (SI), Catalan Democracy (DC), Popular Unity Candidacy (CUP), and Democratic Convergence of Catalonia (CDC) all with representation in the Catalan Parliament. Other independentist parties, with no parliamentary representation, include, Estat Català and Reagrupament, among others. (Note that Convergence and Union (CiU) is a coalition of Convergència Democràtica de Catalunya (CDC) and Unió Democràtica de Catalunya (UDC), which has been holding the regional government, Generalitat de Catalunya between 1980-2003 and from 2010. This coalition has been finished in June 18, 2015, when UDC didn't accept CDC position supporting Catalonia independence[9])

Despite some Catalan nationalists considering the Catalan-speaking regions (Principality of Catalonia, Valencian Community, Balearic Islands, Andorra, Northern Catalonia, (France), and some adjacent territories) as part of the same nation or ethnic group, the Països Catalans, and more broadly the territories where the Catalan language is spoken, Catalan nationalism is only widespread within the borders of the Autonomy.

The inhabitants of Val d'Aran still speak their own dialect of the Occitan language in addition to Catalan and Spanish, and are considered part of the Occitan nation despite the fact that the Aranese territory has been part of Catalonia for centuries.

In 2005, in a vote to pass a draft of a new Statute of Autonomy, 88.9% of the members of the Parliament of Catalonia declared Catalonia a nation, but this was finally changed back to 'nationality' by the decision of the Spanish Parliament and approved in a referendum; however, this statute mentions the word "nation", referring to Catalonia, in its preamble (with declaratory, but not legal value).[10]

In 2012, during the celebration of the Catalan National Day, a huge demonstration jolted the political debate on independence of Catalonia. President Artur Mas called snap elections for the Parliament of Catalonia to be held on 25 September and argued, referring to the demonstration, that "the street vocal must be moved to the polls".

Aragon

- (Nationalism: CHA 4.6%, Aragonese Bloc 0.09%; "Regionalism": PAR 6.86%, Commitment with Aragon 0.43% Aragonese parliamentary election, 2011)

In the past it was an independent kingdom that, along with others, created the Crown of Aragon, that later merged with the Crown of Castile to forge Spain. While there is some pro-independence support, most of Aragon's population does not seek an independent state but to be fully recognized as a distinct and important region in Spain. There is also a claim for the Aragonese language, spoken in the northernmost area, to enjoy full official support. Its Statute of Autonomy defines this region as a nationality.

At the moment, the most important independentist organizations or parties like Puyalon de Cuchas, Purna, A Enrestida, SOA or SEIRA are included in the Bloque Independentista de Cuchas (BIC)

Galicia

From 2005 to 2009 Galicia was ruled by a coalition government between the Socialists' Party of Galicia (PSdeG-PSOE) and the nationalist Galician Nationalist Bloc (BNG). Unlike in other Spanish autonomous communities, the conservative Galician People's Party includes "Galicianism" (strong regionalism or even moderate nationalism) as one of its ideological principles.[11] Even the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party has a quite strong regional flavour in Galicia.[12][13] This issue somehow explains electoral behaviour in Galicia and why nationalist parties have a reduced representation when compared to Catalonia or the Basque Country, as voters in Galicia may choose to go for Spanish parties promoting Galicianism depending on the circumstances. Spanish parties in Catalonia and Basque Country, namely the People's Party, do not have such a strong regional identity.

The BNG is itself a coalition of parties, some of which endorses independence, like the UPG and the Galician Movement for Socialism. Since the 2013 national assembly, BNG claims for national sovereignty, independence[14] and strong promotion of Galician culture and language. Other nationalist parties stand for outright independence, and until recently they only had representatives in local councils and not in the Parliament of Galicia. In the 2012 election the newly formed Galician Left Alternative (AGE), which includes independentist groups, overtook the BNG in Parliament, winning 9 seats. Galician nationalism is present in the majority of galician social movements, especially in the Galician language defense movement (A Mesa pola Normalización Lingüística (The Panel for Language Normalization), Queremos Galego (We Want Galician), AGAL, ...). It's also present in the ecologist movement (ADEGA, Verdegaia, Nunca Máis (Never Again),...). Nationalism is also present in organized labour and trade unions, in fact, the most important union of Galicia is the left-wing nationalist Confederación Intersindical Galega (Galician Interunion Confederation), with more than 80,000 members and 5,623 delegates.[15]

The present Galician Statute of Autonomy of 1981 defines Galicia as a nationality. The former (2005–2009) Galician Government tried to draft a new Statute of Autonomy where Galicia would most probably have been defined as a nation (with declaratory, but not legal value).[16] This was put on halt after the 2009 elections, following the win of the conservative People's Party.

Asturias

- (Nationalism: 1.25% URAS PAS, 0.65% Unidá, 0.46% Andecha Astur Regionalism: 24.83% Asturias Forum)

Nationalist parties (e.g., Andecha Astur) do not get much support from the population, but they clearly have an identity.

A wish for independence is stated sometimes by those parties, but as the independent and pre-Spanish Kingdom of Asturias was the initial core of the Reconquista, most of the people do not feel that there is any incompatibility in being Asturian and Spanish. Moreover, Asturian nationalist and regionalist claims are divided among independence, regionalism itself, conforming an autonomous community with Leon. Their sign of identity is the Asturian language.

The most important regionalist (not nationalist) party is Asturias Forum (Forum Asturias,FAC), which split from the national centre-right People's Party in 2011. It was in government from 2011 to 2012.

Canary Islands

- 33.87% Canarian parliamentary election, 2015: CC (19.9%), New Canaries (10.2%), Nationalist Canarian Centre-United (3.59%), Canarian Nationalist Alternative (0.62%) and Movement for the Canarian People's Unity (0.19%)

Canarian nationalism has its roots in a number of events in the 19th century. Wars for independence in South America, self-government during the Napoleonic invasions, and the crisis of 1898 were the catalyst for figures such as Nicolás Estévanez or Secundino Delgado. After a pause of several decades, a new nationalist movement has emerged there.

Its insularity requires several specific treatments. Over history the Canary Islands acquired special competences and privileges. In former times they even had the right to issue currency and their inhabitants were only obliged to perform military service milicias insulares within the Islands. The Islands were also governed by unique institutions called Cabildos insulares.

Franco's government continued this tradition and conceded several privileges to the islands to compensate for their remoteness.

Its Statute of Autonomy defines this region as a nationality.

The Canarian Government is drafting a new Statute of Autonomy where the Canary Islands will be defined as a nation. However this nationalism is mild in its formulation; thus independence is not even in the nationalist agenda. Historically, the Canarian Coalition can be deemed more as a lobby in order to favour Canarian interests within Spain rather than a nationalist movement like the ones formulated in other areas.

Valencia

- (Nationalism: 18.78% Coalició Compromís (18.46%), Som Valencians (0.28%); Other 4.32% Acord Ciutadà includes the independentist Republican Left of the Valencian Country and the more moderate valencianist United Left of the Valencian Country)

Valencian (a southern dialect of the Catalan language) is spoken alongside Spanish in around two thirds of the territory of the Valencian Community and in most of the more densely populated coastal areas. It is absent in one third of the territory (mostly inland and in the far south) where only Spanish is spoken. Furthermore, in the last 2 centuries Spanish has become the dominant language in the two main cities of Alicante and Valencia. Nationalist sentiment is not widespread and most of the population consider themselves as much Valencian as Spanish. It should also be highlighted that the agenda of the Compromís coalition focuses on fighting corruption which has affected the region during the decades of Partido Popular government and a significant portion of their voters do not identify with Valencian nationalism. Indeed, Compromís have significantly reduced their nationalist discourse in order to gain wider appeal among Valencian voters and have been often accused of camouflaging their ideology.[17]

The nationalist sentiment is not significantly higher in any province (electoral results show that just about 8% of the votes in Castellon, the closest province to Catalonia, are nationalist, higher in the provinces of Valencia with 10.43% and Alicante with 9.06%, according to municipal elections held in May 2007).

Notwithstanding, their electoral stronghold yielding most favourable results is an area split in two provinces: the southernmost end of the Valencia province and the northernmost end of Alicante province. The fact that this area is split between two provinces reduces relative percentages in both provinces.

It is in the local elections that the nationalists obtain their best results; thus they hold several town councils and significant representation - mostly in the areas mentioned above. Conversely, it is in the general elections to the Spanish Parliament where they score worst (approximately 2% of the votes). In the regional elections to the Autonomous Parliament, the main nationalist party Valencian Nationalist Bloc (BNV) usually gets around 4% of the votes, not having yet achieved the 5% threshold which grants representation in the regional Parliament.

There are territories in the Valencian autonomous community which are solely Spanish-speaking areas, where Valencian either was never spoken (roughly the inner 1/3 of the territory) or was historically sparsely spoken and finally disappeared (the southernmost part of the autonomous community, around the city of Orihuela). These territories comprise approximately 25% of the whole autonomous community. Since Valencian nationalism is primarily built around the Valencian language, this political option is virtually non-existent in these areas.

In contrast to the Valencian Union, the BNV and its forebears favour cooperation and ties with the other Catalan speaking territories and greater autonomy - if not independence itself - from Spain, in form of the Països Catalans.

Esquerra Valenciana is a party "of national, republican and transforming left of the Valencian Country; that fights for the political sovereignty and defends the free confederation of this territory with Catalonia and the Balearic Islands". It has not so far achieved electoral representation of any kind.

Its Statute of Autonomy defines this region as a nationality.

Regionalism

In most of these following regions people do not sense a conflict between Spanish nationality and their own claimed national or regional identity.

There are two main political streams in regionalism: Nationalism-Regionalism, which supports the definition of the region as a nationality or nation but usually within Spain, and Regionalism, which originally supported the creation of an autonomous community for its region, and now acts as a promoter of its region but within Spain and respecting the current status of autonomous community, as in the Regionalist Party of Cantabria, that currently rules Cantabria supported by the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party (PSOE)). Some of these regionalist parties are associated with People's Party in its region or acting as its substitute or branch, as in the Navarrese People's Union (UPN)), (see Federation of Regionalist Parties). The following regions have belonged to different kingdoms, realms, states or regions for a time, and their population regularly consider themselves differently mostly depending on the part of the region. Some of these want to be identified with their own regional identity, such as Navarre, Cantabria or Valencia.

Castile

.svg.png)

- (Nationalism-Regionalism: Castile-León 0.81% + Castile La Mancha 0.12% TC)

Regionalists and nationalists in Castile (such as Commoners' Land) usually want to unify the traditional provinces mentioned in the Castilian Federal Pact signed by the Partido Republicano Federal in 1869, and that would include the modern communities of Castile and León, Cantabria, La Rioja, Castilla-La Mancha and Madrid, and sometimes even some areas in the provinces of Valencia, Alicante and Murcia (since Commoners' Land makes no mention of those once Castilian possessions in its ideological bases).[18] The territory claimed by Castilian regionalists or nationalists contains both areas from the Kingdom of Castile (both Old Castile and New Castile) and areas from the Kingdom of León. Their claims are not usually based on the territory of the historical Crown of Castile, as it included the Basque or the Galician nations, they just hold a claim over the provinces that can be identified with Castilian identity according to them. They don't usually hold any claim over Andalusia, Extremadura, or Murcia.

León

Regionalists and nationalists from León fight for an independent autonomous community for the Leonese Country, the Spanish provinces of León, Zamora and Salamanca.

Nationalists from León claims too for the Unity, Selfgovernment and Officiality for the Leonese language in the Bragança District in Portugal and other irredent territories like Valdeorras in Galicia or other ones in the border with Castile.

Leonesism is the third political force in this territory after the autonomous electionships (2007), with more than 300 city councillors in the provinces of León, Zamora and Salamanca.

Leonesist party UPL (Leonese People's Union), the biggest one, reached three seats in the Leonese City Council, where they govern with the PSOE; one deputy in the Diputación de León (provincial council) and two autonomical seats in the Castile and León's Parliament. There is also a small independentist movement led by AGORA País Llionés and Conceyu Xoven.

Cantabria

- (Regionalism: 30.00% PRC, main governing party in coalition with the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party)

The Duchy of Cantabria founded the Kingdom of Asturias and later the region formed part of the Kingdom of Castile, being known outside the territory as La Montaña ("The Mountain").[19][20] However Cantabria kept its particular culture and economy due to its geographic peculiarities and isolation from Castile, relating more naturally to the Northern peoples of Asturias and Biscay. Note that the eastern coast (Castro Urdiales, Laredo) is a residential area for Basques of Biscay. The pre-Roman, Roman and Visigothic name of Cantabria (after the Cantabri) was officially established for the first province of Cantabria in 1778 instead of the exonim La Montaña or the subsequent name imposed by the central government in 1833 province of Santander. Its Statute of Autonomy could not be enacted during the Second Spanish Republic (1931–39) because of the Spanish Civil War. In its current Statute of Autonomy, Cantabria is named a 'Historic Community'.

Navarre

People from Navarre may feel to be either Basque or Spanish, and their culture is more akin to either Aragon or La Rioja in the southern and eastern parts, but in the northern part they identify mostly as Basques, and Basque language is spoken. In historical times Basque was also the local language in several areas of central Navarre where it is no longer spoken natively, with a general south-to-north movement of the Basque-Romance isogloss. Basque is not known to have ever been spoken in southern Navarre, though.

As stated by the Basque Statute of Autonomy, if approved by the Navarrese Parliament and popular referendum by majority, Navarre can join the autonomous community of the Basque Country at any time when its government and population so desires; no further action is required. Navarre is not an Autonomous Community de jure (although it is de facto) because a Statute of Autonomy was not made or approved by popular referendum (as happened in each Autonomous Community). Instead, it is ruled by a document called "Amejoramiento del Fuero" (in Spanish) or "Foru hobekuntza" (in Basque) (Improvement of the Fuero) and the region is considered a "Foral Community".

According to the Ley Foral del Vascuence ("Foral Law regarding Basque Language") of the Navarrese Parliament is divided in three linguistical areas: Basque speaking area (Zona Vascófona); Spanish speaking area with some facilities to the Basque speakers (Zona Mixta), and Spanish monolingual speaking area (Zona No Vascófona).

Valencia

Valencian regionalism marked with anti-Catalan sentiment is also called valencianism or blaverism (named after the fringe which distinguishes the Valencian flag from other flags with a common origin, particularly from the Catalan). Its adherents consider Valencian to be distinct from Catalan and called for autonomous community to be named "Kingdom of Valencia", as opposed to the term País Valencià which may imply an identification with the Països Catalans or Catalan Countries. Only a minor tendency within valencianism/blaverism proposed independence of the Kingdom of Valencia from both Catalonia and Spain.[22]

Balearic Islands

- ("Balearic" nationalism or regionalism: 23.29% More for Majorca, Més per Menorca, Proposta per les Illes)

Catalan is the co-official language in the region. It is very used in rural zones and a little less in the capital and in places with a high density of tourists. Balearic Catalan has developed into various dialectal variants that take their names from the names of the islands ("mallorquí", "menorquí", "eivissenc" and "formenterenc"). Though there are more Catalan nationalistic sympathizers than in Valencia, Spanish nationalism is highly present on the islands and it is considered a traditionally right-winged territory.

Eastern Andalusia

.svg.png)

There is a regionalist movement in the eastern part of Andalusia (mainly Granada, Almería and Jaén, but with also some support in Málaga) which seeks to create an own autonomous community separated from western Andalusia. Historically, Granada was the last Arab kingdom inside the Iberian Peninsula, and had its own administrative region until 1933 when Blas Infante unified the Andalusian provinces. The Platform for Eastern Andalusia [23] has contributed to expand the movement. Among the reasons for the movement, the most important are economical, like benefiting from Spanish decentralization, as opposed to Sevilian centralism, but also historical. The movement is not associated to a particular political thought,[24] and there is not a particular political party aiming to create the new autonomous community.

Rioja

The autonomous community of La Rioja has a regionalist political party, Riojan Party, with 6% of the vote in 2007. There is a strong regionalist sentiment in the community according to surveys. The 90% of the people say feel only Riojan and Spaniard.[25]

Extremadura

- ("Regionalism": 0.06% EU)

This region was conquered partly by the Kingdom of Castile, partly by the Kingdom of León and partly by the united Crown of Castile, but following the reconquest it received numerous settlers from Leon region, particularly in the north of the Caceres province. However, overall its culture is markedly southern and close to that of western Andalusia. Historically, Extremadura grew to become what it is now when some Extremaduran towns united to buy the right to vote in the Cortes for 80.000 ducats.

The Spanish spoken in Extremadura is typically southern, but it also has its own distinctive features which are more prominent in the North-West area, where the local rural dialect is even considered a language of its own, the Extremaduran language; it has common points with the Astur-Leonese linguistic group.

There are a few border areas where varieties close to Portuguese are spoken, for example near Olivenza, town over which the Portuguese Republic holds a claim.

Regionalist movements also exist here.

La Mancha

- (>0% PRM)

Mancheguian regionalism proposes that La Mancha is a region with its own identity, in the territories of the four provinces; Albacete, Ciudad Real, Cuenca, and Toledo. It has his its origins Mancheguismo that opposed the pan-Castilian thesis manifested foremost in Castilian nationalism.

Murcia

- (>0%)

This Mediterranean region belonged to the Taifa kingdoms of Al-Andalus, Aragon, and Castile; therefore, it shares many similarities with Andalusia, Valencia - due to relatively recent immigration a dialect of Valencian-Catalan is spoken among some of the 697 inhabitants (INE 2006) of Carche- and Castilla-La Mancha.

There have been and there are some regionalist movements too. Their goal is to restore the traditional region of Murcia (including Albacete and maybe Almería, and to create the province of Cartagena).

The haven of Cartagena declared itself an independent canton in 1868.

Murcian and Manchegue identity are related by historical links.

Ceuta and Melilla

There are two identities in these African cities. The Spanish-speaking Christians feel similar to Andalusians, a minority of Christians (around 25% in Ceuta) also having Catalan roots, but Ceuta also has a bit of Portuguese essence and Melilla was in close contact with the French in the 19th century.

The bilingual Muslims speak Arabic in Ceuta and Berber in Melilla, besides Spanish and have familiar, commercial and cultural relations with neighbour Morocco. Nevertheless, they generally maintain their political allegiance to Spain, despite the Moroccan claim on the two cities. This Berber language is used sometimes between the Spanish People of the city (Muslims, Christians, Jews, others), specially of Melilla like the Franco-Moroccan language. (lingua franca), many words are adapted by daily trade with Morocco and Algeria during the French colonial period from 1830 to 1962.

Sephardic minorities evidently feel more strongly Spanish and many have emigrated or changed their work home as business headquarters to other towns in Southern Spain, especially Málaga. Nevertheless, they too have strong cultural ties with Morocco. Also there is an Indostai (South Asian) minority from two centuries when the Spaniards, Portuguese and French had colonies in India and Africa.

Conflicts with "nationality" and "nation" and related controversy in Spain

The rest of the autonomous communities (Asturias, Cantabria, Castile and León, La Rioja, Navarre, Madrid, Extremadura, Castile La Mancha, Murcia, and Balearic Islands) are defined as regions.

Aragon, Catalonia, the Balearic Islands and Valencia were part of the same state-kingdom under the Crown of Aragon before the Spanish unification.

- The two terms do not have the same meaning, but are used indistinctively by nationalist parties when justifying their political plans within the Spanish Constitution (nationality is regarded as a euphemism of nation).

- The Spanish Socialist Workers' Party government under José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero has promoted the concept of Spain as a "Nation of nations"[26] to integrate nationalist claims within Spain, despite the ambiguous statement in the Spanish Constitution of 1978. It is non-constitutional for a region or nationality to declare itself a nation while inside the Spanish Nation.

- Apparently, it is stated that an autonomous community of Spain can be either a nationality or a region, thus composing Spain of nationalities (Basque Country, Catalonia, Galicia, Andalusia, Aragon, Valencia, Balearic Islands and Canary Islands) and regions (the rest of Spain), but this is not explicitly specified anywhere in the constitution.

- The Spanish Constitution of 1978 makes Spain a decentralized state, which functions almost as a federation of states in fact.

- Even if an autonomous community declares itself a nationality (and it does have the constitutional right to do that) that does not actually mean anything radically different from a region, since the degree of autonomy is determined both by historical identity, i.e., whether they received a Statute of Autonomy during the Second Republic or not, and by the will of the people. In the 1980s, the statutes of the "historic nationalities" were approved in a "fast track" before those of the rest of the regions.

- The Spanish Government does not recognize the right of self-determination for the hypothetical underlying nationalities or nations and will not respect the outcome of an eventual regional referendum regarding the subject of self-determination or independence. However, the Basque Parliament voted for recognizing this right in its region.

- The term nationality refers only to the "autonomous community", and not to its citizens. That is, an autonomous community can be a nationality, but that does not imply that their citizens (also) have the nationality of that community, but only Spanish nationality. There is only a Spanish citizenship officially recognized.

- Nationalities and hypothetical nations in Spain are not always based on ethnic criteria (as in the case of Basque Country, Catalonia and Galicia) but on historical, linguistic and cultural facts which any person in those regions can assume and become identified with, regardless of his origin, family homeland or the fact that his ancestors belonged to different nationalities.

- Modern "peripheral" (opposed to "central" nationalism) nationalist movements in Spain (such as Basque nationalism, Catalan nationalism, Galician nationalism, Canarian nationalism, etc.) do not regard their "nations" as superior or better in any sense than any other one (although the founder of Basque nationalism thought so), just as distinct from the Spanish one.

This is further complicated by the fact that while in most countries nationalism at a local level equals separatism, in Spain, nationalists are not necessarily separatists (although admittedly many are). As an example, there are clearly defined nationalist parties that support separation from the Spanish state, like the Republican Left of Catalonia. But, there are nationalist parties that purposefully do not state clearly their position on independence (as to maximize electoral success) and sway repeatedly between greater descentralization of the Spanish state and outright separation, like Convergence and Union, Basque Nationalist Party, and Galician Nationalist Bloc.

See also

Spanish peoples

- Andalusians

- Asturians

- Aragonese people

- Basques

- Canary Islanders

- Cantabrian people

- Castilians

- Catalans

- Extremadurans

- Galicians

- The formerly nomadic Gitanos are distinctly marked by high (yet falling) levels of endogamy and persisiting social stigma and discrimination. Although they are dispersed throughout the country, nearly half of them live in Andalusia where they enjoy much higher levels of integration and social acceptance and are a core element of Andalusian identity.[27][28][29][30]

Languages of Spain

Official languages

Recognised languages

Unofficial languages

Others

- Autonomous communities of Spain

- Provinces of Spain

- Historical regions of Spain

- Autonomist and secessionist movements in Spain

- The nationality debate in Spain

- Identities in Spain

- Coconstitutionalism

- Languages of Iberia

- Fueros

- Ethnic groups of Spain

- History of the regional distinctions of Spain

- Nationalities and regions of Spain

References

- ↑ "Llibre dels feits del rei en Jacme [Manuscrit] - Biblioteca Virtual Miguel de Cervantes". Cervantesvirtual.com. 2010-11-29. Retrieved 2016-09-15.

- ↑ Calvo, José. La guerra de Sucesión. Madrid: Anaya, 1988. Breve análisis de una guerra que marcó la aparición de un nuevo Estado, más centralizado, que no olvida el marco internacional en que ésta tuvo lugar

- ↑ NACIONALISMO, FRANQUISMO Y NACIONALCATOLICISMO (EL ESTADO DE LA CUESTIÓN, 11) ISBN 978-84-9739-068-2 Nº Edición:1ª Año de edición:2008 Plaza edición: MADRID

- ↑ "Microsoft Word - Informe Andalucia" (PDF). Huespedes.cica.es. Retrieved 2016-09-15.

- ↑ The abertzale party Batzarre participated in the coalition Izquierda-Ezkerra with the United Left of Navarre , which obtained the 3.69% of the vote and seats (1 for United Left of Navarre and 1 for Batzarre)

- ↑ "LAB izan da 2011. urtean Hego Euskal Herrian ordezkaritza gehien igo duen sindikatua". Labsindikatua.org. Retrieved 2016-09-15.

- ↑ "LAB llama a movilizarse contra la "agresión directa" al sindicato | Diario Público". Publico.es. 2009-10-14. Retrieved 2016-09-15.

- ↑ "Elecciones Generales 2011 - Congreso - Catalunya". Elecciones.mir.es. Retrieved 2016-09-15.

- ↑ "Convergència enterra la federació: "El projecte polític de CiU s'ha acabat i cal una separació amistosa"". Ara.cat. 2015-06-18. Retrieved 2016-09-15.

- ↑ "Europe | Spain MPs back Catalonia autonomy". BBC News. 2006-03-30. Retrieved 2016-09-15.

- ↑ Frans Schrijver. Regionalism After Regionalisation: Spain, France and the United Kingdom. Books.google.com. p. 161. Retrieved 2016-09-15.

- ↑ "Anosaterra". Anosaterra.org. Retrieved 2016-09-15.

- ↑

- ↑ Faro de Vigo (19 March 2013). "Vence fija la independencia como meta del BNG y propone vías de cooperación con Beiras". Retrieved 20 March 2015.

- ↑ "Análise resultados Eleccións Sindicais en Galiza a 31/12/2007" (PDF). Galizacig.com. Retrieved 2016-09-15.

- ↑

- ↑ "Compromís oculta su nacionalismo pero da libertad para ir a la Diada | Comunidad Valenciana | EL MUNDO". Elmundo.es. Retrieved 2016-09-15.

- ↑ "Bases TC-PNC". Web.archive.org. 2002-01-07. Retrieved 2016-09-15.

- ↑ Bar Cendón, Antonio; De La Montaña a Cantabria. Ed. University of Cantabria (1995). ISBN 978-84-8102-112-7.

- ↑ See es:La Montaña for an explanation in Spanish of the usage of this name.

- ↑ "Nafarroako Parlamenturako hauteskundeak, 2015 - Behin betiko emaitzak - Comunidad Foral de Navarra". Elecciones2015.navarra.es. Retrieved 2016-09-15.

- ↑ "Independència Valenciana". Independenciavalenciana.blogspot.com. 2004-02-26. Retrieved 2016-09-15.

- ↑ "AndalucíaOriental.es » Portal oficial de la Asociación "Plataforma por Andalucía Oriental"". Andaluciaoriental.es. Retrieved 2016-09-15.

- ↑

- ↑ "PREELECTORAL ELECCIONES : AUTONÓMICAS 2015. COMUNIDAD : AUTÓNOMA DE LA RIOJA" (PDF). Datos.cis.es. Retrieved 2016-09-15.

- ↑ "Montilla asegura que España es una 'nación de naciones' y la reforma constitucional debe recoger la 'singularidad'", Europa Press, August 8, 2004. However, compare José Bono Martínez: "más como nación de ciudadanos iguales en derechos y obligaciones que como nación de naciones o Estado de pueblos", Ministry of Defence, November 8, 2005.

- ↑ "El pueblo gitano, un pilar fundamental de la identidad cultural andaluza". Andaluciadiversa.com. 2014-04-15. Retrieved 2016-09-15.

- ↑ "El pueblo gitano reivindica su aportación a la cultura andaluza - La Opinión de Málaga". Laopiniondemalaga.es. 2015-11-23. Retrieved 2016-09-15.

- ↑ Integration, Erasure, and Underdevelopment: The Everyday Politics and ... Books.google.es. p. 25. Retrieved 2016-09-15.

- ↑ "Andalucía sigue siendo "un referente en la integración social de gitanos"". Europapress.es (in Spanish). 2015-11-23. Retrieved 2016-09-15.

- ↑ "Boletín Oficial de Aragón electrónico". Boa.aragon.es. Retrieved 2016-09-15.

- ↑ "Llei d'Usu y Promoción del asturianu/bable de 1998". Wikisource.org. Retrieved 2016-09-15.

Further reading

- Amersfoort, Hans Van & Jan Mansvelt Beck 2000 'Institutional Plurality, a way out of the Basque conflict?', Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, vol. 26. no. 3, pp. 449–467

- Antiguedad, Iñaki (et al.):Towards a Basque State. Territory and socioeconomics, Bilbo: UEU, 2012 ISBN 978-84-8438-423-6

- Conversi, Daniele 'Autonomous Communities and the ethnic settlement in Spain', in Yash Ghai (ed.) Autonomy and Ethnicity. Negotiating Competing Claims in Multi-Ethnic States. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000, pp. 122–144 [ISBN 0-521-78642-8 paperback]

- Flynn, M. K. 2004 'Between autonony and federalism: Spain', in Ulrich Schneckener and Stefan Wolf (eds) Managing and Settling Ethnic Conflicts. London: Hurst

- Heywood, Paul. The Government and Politics of Spain. New York St. Martin's Press, 1996 (see in particular ch. 2)

- Keating, Michael. 'The minority nations of Spain and European integration: A new framework for autonomy?', Journal of Spanish Cultural Studies, vol. 1, n. 1, March 2000, pp. 29–42

- Lecours, André 2001 'Regionalism, cultural diversity and the state in Spain', Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, vo. 22, no. 3, pp. 210–226

- Magone, Jose' M. 2004 Contemporary Spanish Politics. London: Routledge, 1997

- Mar-Molinero, Clare. 'The Iberian peninsula: Conflicting linguistic nationalisms', in Barbour, Stephen and Cathie Carmichael (eds) Language and Nationalism in Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000

- Moreno, Luis. 'Local and global: Mesogovernments and territorial identities'. Madrid: Instituto de Estudios Sociales Avanzados (CSIC), Documento de Trabajo 98-09, 1998. Paper presented at the Colloquium on ‘Identity and Territorial Autonomy in Plural Societies’, IPSA Research Committee on Politics and Ethnicity. University of Santiago (July 17–19, 1998), Santiago de Compostela, Spain [URL: http://www.csic.es/iesa/dt-9809.htm, 9 September 1998]

- Mateos, Txoli (et al.):Towards a Basque State. Citizenship and culture, Bilbo: UEU, 2012 ISBN 978-84-8438-422-9

- Moreno, Luis. The Federalization of Spain. London; Portland, OR: Frank Cass, 2001

- Núñez Seixas, X.M.(1993): Historiographical approaches to nationalism in Spain, Saarbrücken, Breitenbach

- Núñez Seixas, X.M.(1999): "Autonomist regionalism within the Spanish state of the Autonomous Communities: an interpretation", in Nationalism & ethnic politics, vol. 5, no. 3-4, p. 121-141. Frank Cass, Ilford

- Paredes, Xoan M. 'The administrative and territorial structure of the Spanish State. Galicia within its framework', in Territorial management and planning in Galicia: From its origins to end of Fraga administration, 1950s - 2004. Unpublished thesis (2004, revised in 2007). Dept. of Geography, University College Cork, Ireland [URL: http://www.xoan.net/recursos/tese/GzinSp.pdf, 27 August 2008], pp. 47–73.

- Zubiaga, Mario (et al.):Towards a Basque State. Nation-building and institutions, Bilbo: UEU, 2012 ISBN 978-84-8438-421-2

External links

- Asturies (Asturian)

- Ibarretxe Plan (Spanish - Multilingual)

- Statute of Autonomy of the Basque Country (1979) (Spanish)

- Statute of Autonomy of Catalonia (1979) (Spanish)

- Statute of Autonomy of Catalonia (2006) (Spanish)

- Statute of Autonomy of Galicia (1981) (Spanish)

- Draft of the new Statute of Autonomy of Galicia (Galician)

- Statute of Autonomy of Andalusia (1981) (Spanish)

- Draft of the new Statute of Autonomy of Andalusia

- Statute of Autonomy of Canarias (1982) (Spanish)

- Statute of Autonomy of Aragon (1982) (Spanish)

- Statute of Autonomy of Valencia (1982) (Spanish)

- Statute of Autonomy of Valencia (2006) (Spanish)

- Andalusia as a nation (Spanish)

- Tierra Comunera

- Detailed linguistic map of the Iberian Peninsula