National Congress of American Indians

| |

| Formation | November 17, 1944 |

|---|---|

| Purpose | American Indian and Alaska Native indigenous rights organization |

| Website |

ncai |

The National Congress of American Indians (NCAI) is an American Indian and Alaska Native indigenous rights organization. It was founded in 1944[1] to represent the tribes and resist federal government pressure for termination of tribal rights and assimilation of their people. These were in contradiction of their treaty rights and status as sovereign entities. The organization continues to be an association of federally recognized and state-recognized American Indian tribes.

History

Historically the Indian peoples of the American continent rarely joined forces across tribal lines, which were divisions related to distinct language and cultural groups. One reason was that most tribes were highly decentralized, with their people seldom united around issues.

In the 20th century, a generation of American Indians came of age who were educated in multi-tribal boarding schools and they learned to form alliances across tribes. They increasingly felt the need to work together politically in order to exert their power in dealing with the United States federal government. In addition, with the efforts after 1934 to reorganize tribal governments, activists believed that Indians had to work together to strengthen their political position. Activists formed the National Congress of American Indians to find ways to organize the tribes to deal in a more unified way with the US government. They wanted to challenge the government on its failure to implement treaties, to work against the tribal termination policy, and to improve public opinion of and appreciation for Indian cultures.

The initial organization of the NCAI was done largely by Native American men who worked for the Bureau of Indian Affairs, and represented many tribes. At the second national convention, Indian women attended as representatives in numbers equal to the men. The convention decided that BIA employees should be excluded from serving as general officers or members of the executive committee. The first president of the NCAI was Napoleon B. Johnson, a judge in Oklahoma. Dan Madrano was the initial secretary-treasurer; he was a Caddo who was serving as an elected member of the Oklahoma State Legislature.[2] From 1945 to 1955, the executive secretary of the NCAI was Ruth Muskrat Bronson, who established the organization's legislative news service.[3]

During the late 20th century, NCAI contributed to gaining changes in legislation to protect and preserve Indian culture, as well as the assertion by many tribes of sovereignty in dealing with the federal government.

In the early 21st century, key goals of the NCAI are:

- Enforce for Indians all rights under the Constitution and laws in the United States;

- Expand and improve educational opportunities provided for Indians;

- Improve methods for finding productive employment and developing tribal and individual resources;

- Increase number and quality of health facilities;

- Settle Indian claims equitably; and

- Preserve Indian cultural values.

Constitution

The NCAI Constitution says that its members seek to provide themselves and their descendants with the traditional laws, rights, and benefits. It lists the by-laws and rules of order regarding membership, powers, and dues. There are four classes of membership: tribal, Indian individual, individual associate, and organization associate. Voting right is reserved for tribal and individual members. According to section B of Article III regarding membership, any tribe, band or group of American Indians and Alaska Natives shall be eligible for tribal membership provided it fulfills the following requirements [4]

- A substantial number of its members reside upon the same reservation or (in the absence of a reservation) in the same general locality.

- It maintain a Tribal organization, with regular officers and the means of transacting business an arriving at a reasonably accurate count of its membership;

- It is not a mere offshoot or fraction of an organized Tribe itself eligible for membership

- It is recognized as a Tribe or other identifiable group of American Indians by the Department of the Interior, Court of Claims, the Indian Claims Commission, or a State. An Indian or Alaska Native organization incorporated/chartered under state law is not eligible for tribal membership.

Organizational structure

The organizational structure of the National Congress of American Indians includes a General Assembly, and Executive Council and seven committees. The up-and-coming executive Board of the NCAI is as follows:

- President: Jefferson Keel of the Chickasaw Nation

- First Vice President: Juana Majel-Dixon of the Pauma Band of Luiseno Mission Indians

- Secretary: Theresa Two Bulls of the Oglala Sioux Tribe

- Treasurer: W. Ron Allen of the Jamestown S'Klallam Tribe of Washington.

In addition to these four positions, the NCAI executive board also consists of twelve area Vice-Presidents and twelve Alternative Area Vice-President.

Executive Director

The executive director of National Congress of American Indians is Jackie (Jacqueline) Pata. She has served as executive director since 2001, and works closely with her family at NCAI. Husband Chris Pata is Systems Administrator and daughter Jamie Gomez is External Affairs Director.

Voting

Every tribe gets a number of votes allocated them specific to the size of each tribe.

Achievements

Members were hot discussion topics and often made headlines in valued newspapers such as The New York Times. The successes of the NCAI over these years have been a policy of non-protesting. As a matter of fact, the NCAI were known in the 1960s to carry a banner with the slogan, “INDIANS DON’T DEMONSTRATE”[5]

- In 1949, the NCAI made charges against Federal job bias towards the Indians

- In 1950, the NCAI influenced the insertion of an anti-reservation clause to the Alaska Statehood Act. This clause removes the ban against reservations for Alaskan Natives.

- On July 8, 1954, NCAI won their fight against legislation that would have allowed the states to take civil and criminal jurisdictions over Indians.

- On June 19, 1952, a self-help parley was opened in Utah where 50 agents for 12 groups proposed several self-help action plans

- Indians had conventions nationwide and dealt with various topics such as health care, employment, and safety issues

- In 2015 The organization successfully lobbied the State of California to ban the term "redskins" which is the name of a pro football team in Washington, from being used by public schools in the state of California. [6]

Internal policy differences

In the early 1960s, a shift in attitude occurred. Many young American Indians branded the older generation as sell-outs and called for harsh militancy. Two important militant groups were born: the American Indian Movement (AIM) and the National Indian Youth Council (NIYC). The two groups protested several conventions.

Ongoing issues

Currently, the NCAI is fighting for improved living conditions on reservations, arguing that 560 tribes are federally recognized but fewer than 20 tribes generate enough wealth from casinos to turn the tribe’s economy around. According to the NCAI website, other current issues and topics include:

- "Protection of programs and services to benefit Indian families, specifically targeting Indian Youth and elders

- Promotion and support of Indian education, including Head Start, elementary, post-secondary and Adult Education

- Enhancement of Indian health care, including prevention of juvenile substance abuse, HIV-AIDS prevention and other major diseases

- Support of environmental protection and natural resources management

- Protection of Indian cultural resources and religious freedom rights

- Promotion of the Rights of Indian economic opportunity both on and off reservations, including securing programs to provide incentives for economic development and the attraction of private capital to Indian Country

- Protection of the Rights of all Indian people to decent, safe and affordable housing."[7]

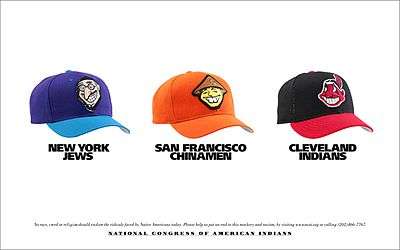

In 2001, the advertising firm of DeVito/Verdi created an advertising campaign and poster for the NCAI to highlight offensive and racist sports team images and mascots.[8] In October of 2013, the NCAI published a report on sports sports teams using harmful and racial "Indian" mascots.[9]

Notable members

- Ruth Muskrat Bronson, Executive Director (1944–48) and a specialist in American Indian Affairs[10]

- Vine Deloria, Jr., Executive Director (1964–1967). He ended major legislative battles

- Susan Shown Harjo, Executive Director (1984–1989)

- J. B. Milam: founding member

- Ira Hayes: American hero during the battle of Iwo Jima, and also made a speech in the congress.

- Nipo T. Strongheart performer-lecture and technical advisor on several Hollywood films involving Native Americans and a cofounder.[11]

Past presidents

- Napolean B. Johnson, Cherokee (1944–1952)[10]

- Joseph R. Garry, Coeur D'Alene (1953–1959)

- Walter Wetzel, Blackfeet (1960–1964)

- Clarence Wesley, San Carlos Apache (1965–1966)

- Wendell Chino, Mescalero Apache (1967–1968)

- Earl Old Person, Blackfeet (1969–1970)

- Leon F. Cook, Red Lake Chippewa (1971–1972)

- Mel Tonasket, Colville (1973–1976)

- Veronica Homer Murdock, Mohave (1977–1978)

- Edward Driving Hawk, Sioux (1979–1980)

- Joseph DeLaCruz, Quinault, (1981–1984)

- Reuben A. Snake, Jr., Ho-Chunk (1985–1987)

- John Gonzales, San Ildefonso Pueblo (1988–1989)

- Wayne L. Ducheneaux, Cheyenne River Sioux (1990–1991)

- gaiashkibos, Lac Courte Oreilles (1992–1995)

- W. Ron Allen, Jamestown S’Klallam (1996–1999)

- Susan Masten, Yurok (2000–2001)

- Tex Hall, Mandan/Hidatsa/Arikara (2002–2005)

- Joe A. Garcia, Ohkay Owingeh (2006–2009)

- Jefferson Keel, Chickasaw (2010–2013)

- Brian Cladoosby, Swinomish (2014–present)

References

- ↑ Cowger, Thomas W. The National Congress of American Indians: The Founding Years. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 1999.

- ↑ Alison R. Bernstein. American Indian and World War II: Toward a New Era in Indian Affairs (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1991) p. 116-119

- ↑ Harvey, Gretchen G. (2004). "Bronson, Ruth Muskrat". In Ware, Susan; Braukman, Stacy. Notable American Women: A Biographical Dictionary Completing the Twentieth Century. 5. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. pp. 80–82. ISBN 978-0-674-01488-6.

- ↑ NCAI by-laws and constitution

- ↑ Shreve, Bradley G. “From Time Immemorial: The Fish-in Movement and the Rise of the Intertribal Activism.” Pacific Historical Review. 78.3 (2009): 403-434

- ↑ http://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/california-becomes-first-state-ban-redskins-nickname-n442561

- ↑ "Our History." National Congress of American Indians. (retrieved 20 Dec 2009)

- ↑ Roller, Emma (2013-10-10). "Old Poster Goes Viral, Teaches Multiple Lessons". Slate. Retrieved 2016-08-31.

- ↑ "Ending the Era of Harmful "Indian" Mascots" (PDF). 2013-10-01. Retrieved 2016-08-29.

- 1 2 Strong Tribal Nations, Strong America, NCAI 67th Annual Convention Program

- ↑ Fisher, Andrew H. (Winter 2013). "Speaking for the First Americans: Nipo Strongheart and the campaign for American Indian citizenship.". Oregon Historical Quarterly. 114 (4): 441–452. ISSN 0030-4727. Retrieved 22 Aug 2014.

Bibliography

- National Congress of American Indians: Constitution, By-Laws and Standing Rules of Order. Found on the official NCAI website, this article was last amended in 2007. It states the purpose of the NCAI, the different types of memberships, and the rules and regulations.

- Deloria, Vine Jr. Custer Died for Your Sins: An Indian Manifesto. New York: Avon Books, 1970. This book explores the reality and myths surrounding Indians, the problems of leadership, and modern Indian affairs.

- Johnson, N B. The National Congress of American Indians. Written by the Justice of Supreme Court of Oklahoma and published in the Chronicles of Oklahoma, this article discusses the formation of the NCAI, and Congress’reaction.

- Report of Activities, American Association on Indian Affairs, June 1945-May 1946. This article discusses the reasons why a nationwide organization of Indians is so crucial.

- Shreve, Bradley G. “From Time Immemorial: The Fish-in Movement and the Rise of the Intertribal Activism”, Pacific Historical Review 78.3 (2009): 403-434, via JSTOR

- Cowger, Thomas W. The National Congress of American Indians: The Founding Years. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 1999.