Nat Turner

| Nat Turner | |

|---|---|

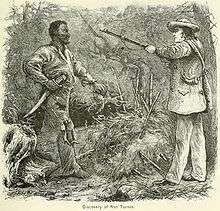

Discovery of Nat Turner (c. 1831–1876) | |

| Born |

October 2, 1800 Southampton County, Virginia, U.S. |

| Died |

November 11, 1831 (aged 31) Jerusalem, Virginia, U.S. |

| Cause of death | Execution by hanging |

| Nationality | American |

| Known for | Nat Turner's slave rebellion |

| Spouse(s) | Cherry Turner |

Nat Turner (October 2, 1800 – November 11, 1831) was an enslaved African American who led a rebellion of slaves and free blacks in Southampton County, Virginia on August 21, 1831, that resulted in the deaths of 55 to 65 white people. In retaliation, white militias and mobs killed more than 200 black people while putting down the rebellion.[1]

The rebels went from plantation to plantation, gathering horses and guns, freeing other slaves along the way, and recruiting other blacks who wanted to join their revolt. During the rebellion, Virginia legislators targeted free blacks with a colonization bill, which allocated new funding to remove them, and a police bill that denied free blacks trials by jury and made any free blacks convicted of a crime subject to sale and relocation.[1] Whites organized militias and called out regular troops to suppress the uprising. In addition, white militias and mobs attacked blacks in the area, killing an estimated 200,[2] many of whom were not involved in the revolt.[3]

In the aftermath, the state quickly arrested and executed 57 blacks accused of being part of Turner's slave rebellion. Turner hid successfully for two months. When found, he was tried, convicted, sentenced to death, and hanged. Across Virginia and other southern states, state legislators passed new laws to control slaves and free blacks. They prohibited education of slaves and free blacks, restricted rights of assembly for free blacks, withdrew their right to bear arms (in some states), and to vote (in North Carolina, for instance), and required white ministers to be present at all black worship services.

Early years

Born into slavery on October 2, 1800, in Southampton County, Virginia, the African-American boy was recorded as "Nat" by Benjamin Turner, the man who held his mother and him as slaves. When Benjamin Turner died in 1810, Nat became the property of Benjamin's brother Samuel Turner.[1] It is unclear whether Nat gave himself the name "Turner" or it was given to him by his master.[4] Turner knew little about the background of his father, who was believed to have escaped from slavery when Turner was a young boy.[5]

Turner spent his entire life in Southampton County, Virginia, a plantation area where slaves comprised the majority of the population.>[6] He was identified as having "natural intelligence and quickness of apprehension, surpassed by few."[7] He learned to read and write at a young age. Deeply religious, Nat was often seen fasting, praying, or immersed in reading the stories of the Bible.[8]

Turner's religious convictions manifested as frequent visions which he interpreted as messages from God. His belief in the visions was such that when Turner was 22 years old, he ran away from his owner; he returned a month later after claiming to have received a spiritual revelation. Turner often conducted Baptist services, preaching the Bible to his fellow slaves, who dubbed him "The Prophet". Turner garnered white followers such as Ethelred T. Brantley, whom Turner was credited with having convinced to "cease from his wickedness".[9]

In early 1828, Turner was convinced that he "was ordained for some great purpose in the hands of the Almighty."[10] While working in his owner's fields on May 12, Turner

heard a loud noise in the heavens, and the Spirit instantly appeared to me and said the Serpent was loosened, and Christ had laid down the yoke he had borne for the sins of men, and that I should take it on and fight against the Serpent, for the time was fast approaching when the first should be last and the last should be first.[11]

“In connecting this vision to the motivation for his rebellion, Turner makes it clear that he sees himself as participating in the confrontation between God's Kingdom and the anti-Kingdom that characterized his social-historical context."[12] He was convinced that God had given him the task of "slay[ing] my enemies with their own weapons."[11] Turner said, "I communicated the great work laid out for me to do, to four in whom I had the greatest confidence" – his fellow slaves Henry, Hark, Nelson, and Sam.[11]

After the rebellion, a reward notice described Turner as:

5 feet 6 or 8 inches high, weighs between 150 and 160 pounds, rather bright complexion, but not a mulatto, broad shoulders, larger flat nose, large eyes, broad flat feet, rather knockkneed, walks brisk and active, hair on the top of the head very thin, no beard, except on the upper lip and the top of the chin, a scar on one of his temples, also one on the back of his neck, a large knot on one of the bones of his right arm, near the wrist, produced by a blow.[13]

Beginning in February 1831, Turner claimed certain atmospheric conditions as a sign to begin preparations for a rebellion against slave owners. On February 11, 1831, an annular solar eclipse was visible in Virginia. Turner envisioned this as a black man's hand reaching over the sun.[14] He initially planned the rebellion to begin on July 4, Independence Day. Turner postponed it because of illness and to use the delay for additional planning with his co-conspirators. On August 13 there was another solar eclipse in which the sun appeared bluish-green, possibly the result of lingering atmospheric debris from an eruption of Mount St. Helens in present-day Washington state. Turner interpreted this as the final signal, and about a week later, on August 21, he began the uprising.[15]

Rebellion

From The Confessions of Nat Turner-[16]

"I entered my master's chamber; it being dark, I could not give a death blow, the hatchet glanced from his head, he sprang from the bed and called his wife, it was his last word. Will laid him dead, with a blow of his axe, and Mrs. Travis shared the same fate, as she lay in bed. The murder of this family five in number, was the work of a moment, not one of them awoke; there was a little infant sleeping in a cradle, that was forgotten, until we had left the house and gone some distance, when Henry and Will returned and killed it..."[17]

"As I came round to the door I saw Will pulling Mrs. Whitehead out of the house, and at the step he nearly severed her head from her body, with his broad axe. Miss Margaret, when I discovered her, had concealed herself in the comer, formed by the projection of the cellar cap from the house; on my approach she fled, but was soon overtaken, and after repeated blows with a sword, I killed her by a blow on the head, with a fence rail."[18]

Turner started with a few trusted fellow slaves. “All his initial recruits were other slaves from his neighborhood”.[19] The neighborhood men had to find ways to communicate their intentions without giving up their plot. Songs may have tipped the neighborhood members on movements. "It is believed that one of the ways Turner summoned fellow conspirators to the woods was through the use of particular songs."[20] The rebels traveled from house to house, freeing slaves and killing the white people they found. The rebels ultimately included more than 70 enslaved and free men of color.[21]

Because the rebels did not want to alert anyone to their presence as they carried out their attacks, they initially used knives, hatchets, axes, and blunt instruments instead of firearms.[22] The rebellion did not discriminate by age or sex, and members killed white men, women and children. Nat Turner confessed to killing only one person, Margaret Whitehead, whom he killed with a blow from a fence post.[22]

Before a white militia could organize and respond, the rebels killed 60 men, women, and children.[23] They spared a few homes "because Turner believed the poor white inhabitants 'thought no better of themselves than they did of negros.'"[23][24] Turner also thought that revolutionary violence would serve to awaken the attitudes of whites to the reality of the inherent brutality in slave-holding. Turner later said that he wanted to spread "terror and alarm" among whites.[25]

Capture and execution

The rebellion was suppressed within two days, but Turner eluded capture by hiding in the woods until October 30, when he was discovered by farmer Benjamin Phipps. Turner was hiding in a hole covered with fence rails. While awaiting trial, Turner confessed his knowledge of the rebellion to attorney Thomas Ruffin Gray, who compiled what he claimed was Turner's confession.[26] On November 5, 1831, Turner was tried for "conspiring to rebel and making insurrection", convicted, and sentenced to death.[27] Turner was hanged on November 11 in Jerusalem, Virginia. His body was flayed, beheaded and quartered, as an example to frighten other would-be rebels.[28] Turner received no formal burial; his headless remains were possibly buried in an unmarked grave. His skull passed through many hands, and in 2002, it was given to Richard G. Hatcher, the former mayor of Gary, Indiana, for the collection of a civil rights museum he planned to build there. In 2016, Hatcher returned the skull to two of Turner's descendants. If DNA tests confirm that the skull was his, they will bury it in a family cemetery.[29]

In the aftermath of the insurrection, 45 slaves, including Turner, and five free blacks were tried for insurrection and related crimes in Southampton. Of the 45 slaves tried, 15 were acquitted. Of the 30 convicted, 18 were hanged, while 12 were sold out of state. Of the five free blacks tried for participation in the insurrection, one was hanged, while the others were acquitted.[30]

Soon after Turner's execution, Thomas Ruffin Gray published The Confessions of Nat Turner. His book was derived partly from research Gray did while Turner was in hiding and partly from jailhouse conversations with Turner before trial. This work is considered the primary historical document regarding Nat Turner, but some historians believe Gray's portrayal of Turner is inaccurate and may have compromised the authenticity of the document.[31]

Consequences

In total, the state executed 55 black people suspected of having been involved in the uprising. But in the hysteria of aroused fears and anger in the days after the revolt, white militias and mobs killed an estimated 200 black people, many of whom had nothing to do with the rebellion.[32]

The fear caused by Nat Turner's insurrection and the concerns raised in the emancipation debates that followed resulted in politicians and writers responding by defining slavery as a "positive good".[33] Such authors included Thomas Roderick Dew, a College of William & Mary professor who published a pamphlet in 1832 opposing emancipation on economic and other grounds.[34] In the 19th century antebellum era, other Southern writers began to promote a paternalistic ideal of improved Christian treatment of slaves, in part to avoid such rebellions. Dew and others believed that they were civilizing African Americans through slavery; most by then were native born, with their own stake in the United States.

Legacy

Interpretations

The massacre of blacks after the rebellion was typical of white fears and overreaction to black violence; many innocent blacks were killed in revenge. African Americans have generally regarded Turner as a hero of resistance, who made slave-owners pay for the hardships they had caused so many Africans and African Americans.[23]

Joseph Drexler-Dreis writes that Turner "was stimulated exclusively by fanatical revenge, and perhaps misled by some hallucination of his imagined spirit of prophecy".[35][36] James H. Harris, who has written extensively about the history of the Black church, says that the revolt "marked the turning point in the black struggle for liberation". According to Harris, Turner believed that "only a cataclysmic act could convince the architects of a violent social order that violence begets violence".[37]

In the period soon after the revolt, whites did not try to interpret Turner's motives and ideas.[25] Antebellum slave-holding whites were shocked by the murders and had their fears of rebellions heightened; Turner's name became "a symbol of terrorism and violent retribution".[23]

In an 1843 speech at the National Negro Convention, Henry Highland Garnet, a former slave and active abolitionist, described Nat Turner as "patriotic", stating that "future generations will remember him among the noble and brave".[38] In 1861 Thomas Wentworth Higginson, a northern writer, praised Turner in a seminal article published in Atlantic Monthly. He described Turner as a man "who knew no book but the Bible, and that by heart who devoted himself soul and body to the cause of his race".[39]

In the 21st century, writing after the September 11 attacks in the United States, William L. Andrews drew analogies between Turner and modern "religio-political terrorists". He suggested that the "spiritual logic" explicated in Confessions of Nat Turner warrants study as "a harbinger of the spiritualizing violence of today's jihads and crusades".[25]

Legacy and honors

- In 2002, scholar Molefi Kete Asante listed Nat Turner as one of the 100 Greatest African Americans.[40]

- In 2009, in Newark, New Jersey, the largest city-owned park to be built was named Nat Turner Park, in honor of his struggle for freedom. The facility cost $12 million in construction.[41]

In literature, film and music

- The Narrative of the Life of Henry Box Brown, a slave narrative by an escaped slave, refers to the rebellion.

- Thomas R. Gray's 1831 pamphlet account, The Confessions of Nat Turner, based on his jailhouse interview with Turner, is reprinted here (pdf)

- William Cooper Nell wrote an account of Turner in his history book The Colored Patriots of the American Revolution; Insurrection at Southampton, 1855

- Harriet Ann Jacobs, also an escaped slave, refers to Turner in her 1861 narrative, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl.

- The Confessions of Nat Turner (1967), a novel by William Styron, won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction in 1968.[42] It prompted much controversy, with some criticizing a white author writing about such an important black figure. Several critics described it as racist and "a deliberate attempt to steal the meaning of a man's life."[43] These responses led to cultural discussions about how different peoples interpret the past and whether any one group has sole ownership of any portion.

- In response to Styron's novel, ten African-American writers published a collection of essays, The Second Crucifixion of Nat Turner (1968).[44]

- Nat Turner's Rebellion is featured in Episode 5 of the 1977 TV miniseries Roots. It is historically inaccurate, as the episode is set in 1841[45] and the revolt took place in 1831. It is also mentioned in the 2016 series.

- In 2007 cartoonist and comic book author Kyle Baker wrote a two-part comic book about Turner and his uprising, which was called Nat Turner.[46]

- In early 2009, comic book artist and animator Brad Neely created a Web animation entitled "American Moments of Maybe", a satirical advertisement for Nat Turner's Punchout! a video game in which a player took on the role of Nat Turner.[47]

- The Birth of a Nation, the 2016 film starring, produced and directed by Nate Parker, co-written with Jean McGianni Celestin, is about Turner's 1831 rebellion.[48] This film, which also stars Gabrielle Union, was sold in January 2016 at the Sundance Film Festival for a record-breaking $17.5 million.

- J. Cole mentions Nat Turner in lyrics to the song "Folger's Crystals." "Nat Turner in my past life, Bob Marley in my last life, back again."[49]

- In the song "Mortal Man," from Kendrick Lamar's album To Pimp A Butterfly, Lamar has a conversation with Tupac Shakur (adapted from an earlier interview), in which the late Shakur says, "It's gonna be like Nat Turner, 1831."[50]

- Lecrae rapped a line in his song "Freedom" that said, "I gave Chief Keef my number in New York this summer, I told him, 'I could get you free,' I'm on my Nat Turner."[51]

- Iin his song "Ah Yeah," KRS-One identifies Nat Turner as one of the personas he inhabited during numerous incarnations on this planet, when he says, "other times I had to come as Nat Turner."[52]

- In his song "How Great," Chance The Rapper makes reference to Turner's rebellion in the line, "Hosanna Santa invoked and woke up slaves from Southampton to Chatham Manor."[53]

See also

- Abraham Lincoln

- Cherry Turner

- Dred Scott

- Dred Scott v. Sandford

- Harriet Tubman

- John Brown (abolitionist)

- List of slaves

Notes

- 1 2 3 Gray White, Deborah (2013). Freedom on my mind: A history of African Americans. New York Bedford/St. Martin's. p. 225.

- ↑ "Nat Turner's Rebellion". Africans in America. PBS. 1998. Retrieved July 17, 2016.

- ↑ American History: A Survey – Brinkley

- ↑ Greenburg 2003, 3-12

- ↑ Greenburg 2003, p18

- ↑ Greenburg 2003, p278

- ↑ Bisson, Nat Turner: Slave Revolt Leader (2005), p. 76.

- ↑ Aptheker (1993), p. 296.

- ↑ Gray, Thomas Ruffin (1831). The Confessions of Nat Turner, the Leader of the Late Insurrections in Southampton, Va. Baltimore, Maryland: Lucas & Deaver. pp. 7–9, 11.

- ↑ Gray (1831), p. 9.

- 1 2 3 Gray (1831), p. 11.

- ↑ Dreis, Joseph (November 2014). "Nat Turner's Rebellion as a Process of Conversion: Towards a Deeper Understanding of the Christian Conversion Process" (Vol. 12 No. 3): 231. Retrieved 10 December 2014.

- ↑ Description of Turner included in $500 reward notice in the National Intelligencer (Washington, DC) on September 24, 1831, quoted in Aptheker, American Negro Slave Revolts, p. 294.

- ↑ Allmendinger 2014, p21-22

- ↑ Allmendinger 2014, p97-98

- ↑ Gray, Thomas Ruffin (1831). The Confessions of Nat Turner, the Leader of the Late Insurrections in Southampton, Va. Baltimore, Maryland: Lucas & Deaver.

- ↑ Gray (1831), p. 11.

- ↑ Gray (1831), p. 13.

- ↑ Kaye, Anthony (2007). "Neighborhoods and Nat Turner". Journal of the Early Republic. 27 (Winter 2007): 705–20. doi:10.1353/jer.2007.0076.

- ↑ Nielson, Erik (2011). "'Go in de wilderness': Evading the 'Eyes of Others' in the Slave Songs". The Western Journal of Black Studies. 35 (2): 106–17.

- ↑ Ayers, de la Tejada, Schulzinger and White (2007). American Anthem US History. New York, New York: Holt, Rhinehart and Winston. p. 286.

- 1 2 Gray, Thomas Ruffin (1831). The Confessions of Nat Turner, the Leader of the Late Insurrections in Southampton, Va. Baltimore, Maryland: Lucas & Deaver.

- 1 2 3 4 Oates, Stephen (October 1973). "Children of Darkness". American Heritage. 24 (6). Retrieved July 17, 2016.

- ↑ Bisson, Nat Turner: Slave Revolt Leader (2005), pp. 57–58.

- 1 2 3 William L. Andrews; ed. Vincent L. Wimbush (2008). "7". Theorizing Scriptures: New Critical Orientations to a Cultural Phenomenon. Rutgers University Press. pp. 83–85.

- ↑ Gray, Thomas (1993). "The Confessions of Nat Turner". American Journal of Legal History. 03: 332–61.

- ↑ Southampton County Court Minute Book 1830–1835, pp. 121–23.

- ↑ Gibson, Christine (November 11, 2005). "Nat Turner, Lightning Rod". American Heritage Magazine. Archived from the original on April 6, 2009. Retrieved 2009-04-06.

- ↑ Fornal, Justin (October 7, 2016). "Inside the Quest to Return Nat Turner's Skull to His Family". National Geographic. Retrieved December 4, 2016.

- ↑ Walter L. Gordon, III, The Nat Turner Insurrection Trials: A Mystic Chord Resonates Today (Booksurge, 2009) pp. 75, 92.

- ↑ Fornal, Justin (October 5, 2016). "Nat Turner's Slave Uprising Left Complex Legacy". National Geographic. Retrieved December 4, 2016.

- ↑ "Africans in America/Part 3/Nat Turner's Rebellion". Pbs.org. Retrieved 2010-08-21.

- ↑ "Virginia Memory: Nat Turner Rebellion". Virginia Memory. Retrieved December 10, 2014.

- ↑ Brophy, Alfred L. (2008). "Considering William and Mary's History with Slavery: The Case of President Thomas R. Dew" (PDF). William & Mary Bill of Rights (Journal 16): 1091. Retrieved 1 July 2012.

- ↑ Dreis, Joseph (November 2014). "Nat Turner's Rebellion as a Process of Conversion: Towards a Deeper Understanding of the Christian Conversion Process". 12 (3): 232. Retrieved 10 December 2014.

- ↑ Drexler-Dreis, Joseph (November 2014). "Nat Turner's Rebellion as a Process of Conversion: Towards a Deeper Understanding of the Christian Conversion Process". Black Theology: An International Journal (published 2015-04-21). 12 (3): 230–50. doi:10.1179/1476994814Z.00000000037. Retrieved 2016-07-17.

- ↑ James H. Harris (1995). Preaching Liberation. Fortress Press. p. 46.

- ↑ Henry Highland Garnet, A Memorial Discourse (Philadelphia: J. M. Wilson, 1865), pp. 44–51.

- ↑ Higginson, Thomas Wentworth. "Nat Turner's Insurrection: An account of America's bloodiest slave revolt, and its repercussions". The Atlantic. The Atlantic Monthly Group. Retrieved 20 October 2013.

- ↑ Asante, Molefi Kete (2002). 100 Greatest African Americans: A Biographical Encyclopedia, Amherst, NY: Prometheus Books. ISBN 1-57392-963-8.

- ↑ "The Trust for Public Land Celebrates Groundbreaking at Nat Turner Park". Pr-inside.com. Retrieved 2010-08-21.

- ↑ "The Pulitzer Prizes | Fiction". Pulitzer.org. Retrieved 2010-08-21.

- ↑ Ebony.

- ↑ "Dr. Molefi Kete Asante – Articles". Asante.net. Retrieved 2010-08-21.

- ↑ "Roots – disc 3-1, part 1". YouTube. Retrieved 2010-08-21.

- ↑ "Kyle Baker's Nat Turner #1". Comicbookbin.com. Retrieved 2010-08-21.

- ↑ "Brad Neely – American Moments of Maybe – Video, listening & stats at". Last.fm. 2008-11-21. Retrieved 2010-08-21.

- ↑ Pedersen, Erik. "'The Birth Of A Nation' Adds To Cast; Ryan Gosling In Talks For 'The Haunted Mansion'". Retrieved 10 April 2015.

- ↑ "J. Cole – Folgers Crystals". Genius. Retrieved 2016-04-20.

- ↑ "Kendrick Lamar – Mortal Man". Genius. Retrieved 2016-04-20.

- ↑ "Lecrae (Ft. N'Dambi) – Freedom". Genius. Retrieved 2016-04-20.

- ↑ "Ah Yeah". Genius. Retrieved 2016-07-14.

- ↑ http://genius.com/9148002

References

- Nat Turner biography, part of the Africans in America series Website from PBS.

- "Nat Turner: A Troublesome Property"

- Digital Library on American Slavery

Further reading

- Allmendinger, David F. Nat turner and the rising in Southampton county. JHU Press, 2014.

- Herbert Aptheker. American Negro Slave Revolts. 5th edition. New York: International Publishers, 1983 (1943).

- Herbert Aptheker. Nat Turner's Slave Rebellion. New York: Humanities Press, 1966.

- Patrick H. Breen. "The Land Shall Be Deluged in Blood: A NEw History of the Nat TUrner REvolt." New York: Oxford University PRess, 2015.

- Alfred L. Brophy. "The Nat Turner Trials". North Carolina Law Review (June 2013), volume 91: 1817–80.

- Drewry, William Sydney (1900). The Southampton Insurrection. Washington, D.C.: The Neale Company.

- Scot French. The Rebellious Slave: Nat Turner in American Memory. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. 2004.

- William Lloyd Garrison, "The Insurrection", The Liberator (September 3, 1831). A contemporary abolitionist's reaction to news of the rebellion.

- Walter L. Gordon III. The Nat Turner Insurrection Trials: A Mystic Chord Resonates Today (Booksurge, 2009).

- Thomas R. Gray, The Confessions of Nat Turner, the Leader of the Late Insurrections in Southampton, Va. Baltimore: Lucas & Deaver, 1831. Available online.

- Greenberg, Kenneth S., ed. Nat Turner: A Slave Rebellion in History and Memory. Oxford University Press, 2003.

- William Stryon, The Confessions of Nat Turner, Random House Inc, 1993, ISBN 0-679-73663-8

- Stephen B. Oates, The Fires of Jubilee: Nat Turner's Fierce Rebellion. New York: HarperPerennial, 1990 (1975).

- Brodhead, Richard H. "Millennium, Prophecy and the Energies of Social Transformation: The Case of Nat Turner," in A. Amanat and M. Bernhardsson (eds), Imagining the End: Visions of Apocalypse from the Ancient Middle East to Modern America (London, I. B. Tauris, 2002), pp. 212–33.

- Kenneth S. Greenberg, ed. Nat Turner: A Slave Rebellion in History and Memory. New York: Oxford University Press, 2003.

- Junius P. Rodriguez, ed. Encyclopedia of Slave Resistance and Rebellion. Westport: Greenwood Press, 2006.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Nat Turner. |

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Nat Turner |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Nat Turner |

- Works by Nat Turner at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Nat Turner at Internet Archive

- The Confessions of Nat Turner, the Leader of the Late Insurrection in Southampton, Va. Baltimore: T. R. Gray, 1831.

- Nat Turner: A Troublesome Property, California Newsreel

- Nat Turner's Rebellion, Africans in America, PBS.org

- Jessica McElrath, Nat Turner's Rebellion, About.com

- Thomas Ruffin Gray, The Confessions of Nat Turner (1831) online edition

- "Nat Turner: Lightning Rod" on the American Heritage website.

- Interview with Sharon Ewell Foster regarding her recent research on Turner, The State of Things, North Carolina Public Radio, August 31, 2011.

- Nat Turner Unchained an independent feature film about the Nat Turner revolt.

- Nat Turner: Following Faith a play about Nat Turner.

- A Rebellion to Remember: Nat Turner

- The Nat Turner Project, a digital library of primary and secondary sources related to the Nat Turner Slave Rebellion