Name of Italy

The name of Italy is at least three thousand years old and has a history that goes back to pre-Roman Italy. It was initially related to the tip of the Italian peninsula actually called Calabria, but during the Roman empire was enlarged to all the Italian geographical region (including the islands of Sicilia, Sardinia and Corsica).

History

Italia, the ancient name of the Italian peninsula, which is also eponymous of the modern republic, originally applied only to a part of what is now Southern Italy.

According to Antiochus of Syracuse, it included only the southern portion of the Bruttium peninsula (modern Calabria):[1][2][3][4] the actual province of Reggio and part of the modern provinces of Catanzaro and Vibo Valentia. The town of Catanzaro has a road sign (in Italian) also stating this fact.[5]

But by this time Oenotria and Italy had become synonymous, and the name also applied to most of Lucania as well. Coins bearing the name Italia were minted by an alliance of Italic peoples (Sabines, Samnites, Umbrians and others) competing with Rome in the 1st century BC.[6]

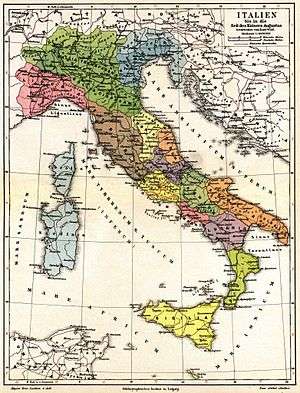

The Greeks gradually came to apply the name Italia to a larger region, but it was during the reign of Augustus, at the end of the 1st century BC, that the term was expanded to cover the entire peninsula until the Alps, now entirely under Roman rule.[7]

Under emperor Diocletian the roman region called "Italia" was further enlarged with the addition of the three big islands of the western Mediterranean sea: Sicily (with the Maltese archipelago), Sardinia and Corsica.

Dante in the Trecento wrote that the borders of what is geographically & historically called "Italia" are clearly defined in the north by the Alps (from the Vare river near Montecarlo to the Arsa river in Istria) and -going down the Italian peninsula- in the south by Sicily and its islands.

Etymology

The ultimate etymology of the name is uncertain, in spite of numerous suggestions.[8] According to the most widely accepted explanation, Latin Italia[9] may derive from Oscan víteliú, meaning "[land] of young cattle" (c.f. Lat vitulus "calf", Umbrian vitlu), via Greek transmission (evidenced in the loss of initial digamma).[10] The bull was a symbol of the southern Italic tribes and was often depicted goring the Roman wolf as a defiant symbol of free Italy during the Social War. Greek historian Dionysius of Halicarnassus states this account together with the legend that Italy was named after Italus,[11] mentioned also by Aristotle[12] and Thucydides.[13]

After the fall of the Western Roman Empire and the Lombard invasions, "Italia" was retained as the name for their kingdom, and for its successor kingdom within the Holy Roman Empire, which nominally lasted until 1806, although it had de facto disintegrated due to factional politics pitting the empire against the ascendant city republics in the 13th century.

See also

References

- ↑ "The Origins of the Name 'Italy'". Arcaini.com. Retrieved 2015-08-25.

- ↑ "History of Calabria - Passion For Italy". Passionforitaly.info. Retrieved 2015-08-25.

- ↑ "+ nome +". Bellevacanze.it. Retrieved 2015-08-25.

- ↑ "italian travel team Calabria - Italy Guide". YouTube. 2011-03-01. Retrieved 2015-08-25.

- ↑ "Billboard image" (JPG). Procopiocaterina.files.wordpress.com. Retrieved 2015-08-25.

- ↑ Guillotining, M., History of Earliest Italy, trans. Ryle, M & Soper, K. in Jerome Lectures, Seventeenth Series, p.50

- ↑ Pallottino, M., History of Earliest Italy, trans. Ryle, M & Soper, K. in Jerome Lectures, Seventeenth Series, p. 50

- ↑ Alberto Manco, Italia. Disegno storico-linguistico, 2009, Napoli, L'Orientale, ISBN 978-88-95044-62-0

- ↑ OLD, p. 974: "first syll. naturally short (cf. Quint. Inst. 1.5.18), and so scanned in Lucil.825, but in dactylic verse lengthened metri gratia."

- ↑ J.P. Mallory and D.Q. Adams, Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture (London: Fitzroy and Dearborn, 1997), 24.

- ↑ Dionysius of Halicarnassus, Roman Antiquities, 1.35, on LacusCurtius

- ↑ Aristotle, Politics, 7.1329b, on Perseus

- ↑ Thucydides, The Peloponnesian War, 6.2.4, on Perseus

External links