Néstor Kirchner

| Néstor Kirchner | |

|---|---|

Kirchner in March 2007 | |

| President of Argentina | |

|

In office 25 May 2003 – 10 December 2007 | |

| Vice President | Daniel Scioli |

| Preceded by | Eduardo Duhalde |

| Succeeded by | Cristina Fernández de Kirchner |

| First Gentleman of Argentina | |

|

In office 10 December 2007 – 27 October 2010 | |

| Preceded by | Cristina Fernández de Kirchner |

| Succeeded by | Juliana Awada Macri |

| Secretary General of the Union of South American Nations | |

|

In office 4 May 2010 – 27 October 2010 | |

| Preceded by | Position established |

| Succeeded by | María Emma Mejía Vélez |

| President of the Justicialist Party | |

|

In office 11 November 2009 – 27 October 2010 | |

| Preceded by | Daniel Scioli |

| Succeeded by | Daniel Scioli |

|

In office 25 April 2008 – 29 June 2009 | |

| Preceded by | Ramón Ruiz |

| Succeeded by | Daniel Scioli |

| Governor of Santa Cruz | |

|

In office 10 December 1991 – 25 May 2003 | |

| Vice Governor |

Eduardo Arnold (1991–1999) Héctor Icazuriaga (1999–2003) |

| Preceded by | Ricardo del Val |

| Succeeded by | Héctor Icazuriaga |

| Mayor of Río Gallegos | |

|

In office 10 December 1987 – 10 December 1991 | |

| Preceded by | Jorge Marcelo Cepernic |

| Succeeded by | Alfredo Anselmo Martínez |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Néstor Carlos Kirchner 25 February 1950 Río Gallegos, Santa Cruz, Argentina |

| Died |

27 October 2010 (aged 60) El Calafate, Santa Cruz, Argentina |

| Cause of death | Heart failure |

| Resting place | Río Gallegos |

| Nationality | Argentine |

| Political party | Justicialist Party |

| Other political affiliations | Front for Victory (2003–2010) |

| Spouse(s) | Cristina Fernández (m. 1975; d. 2010) |

| Children | 2 (notably Máximo) |

| Alma mater | National University of La Plata |

| Profession | Lawyer |

| Signature |

|

Néstor Carlos Kirchner (Spanish pronunciation: [ˈnestoɾ ˈkaɾlos ˈkiɾʃneɾ]; 25 February 1950 – 27 October 2010) was an Argentine politician who served as President of Argentina from 2003 to 2007 and as Governor of Santa Cruz from 1991 to 2003. Ideologically a Peronist and social democrat, he served as President of the Justicialist Party from 2008 to 2010, with his political approach being characterised as Kirchnerism.

Born in Río Gallegos, Santa Cruz, Kirchner studied law at the National University of La Plata. Although the Dirty War had begun, Kirchner did not take an active role. He met and married Cristina Fernández at this time, returned with her to Río Gallegos at graduation, and opened a law firm. Kirchner ran for mayor of Río Gallegos in 1987 and for governor of Santa Cruz in 1991. He was reelected governor in 1995 and 1999 due to an amendment of the provincial constitution. Kirchner sided with Buenos Aires provincial governor Eduardo Duhalde and President Carlos Menem (1989–1999). Although Duhalde lost the 1999 presidential election, he was appointed president by the Congress when previous presidents Fernando de la Rúa and Adolfo Rodríguez Saá resigned during the December 2001 riots. Duhalde suggested that Kirchner run for president in 2003 in a bid to prevent Menem's return to the presidency. Menem won the presidential election but, fearing that he would lose in the required runoff election, he resigned; Kirchner became president as a result.

Kirchner took office on May 25, 2003. Roberto Lavagna, credited with the economic recovery during Duhalde's presidency, was retained as minister of economy and continued his economic policies. Argentina negotiated a swap of defaulted debt and repaid the International Monetary Fund. The National Institute of Statistics and Census intervened to underestimate growing inflation. Several Supreme Court judges resigned (fearing impeachment), and new justices were appointed. The amnesty for crimes committed during the Dirty War in enforcing the full-stop and due-obedience laws and the presidential pardons were repealed and declared unconstitutional. This led to new trials for the military who served during the 1970s. Argentina increased its integration with other Latin American countries, discontinuing its automatic alignment with the United States dating to the 1990s. The 2005 midterm elections were a victory for Kirchner, and signaled the end of Duhalde's supremacy in Buenos Aires Province.

Instead of seeking reelection, Kirchner stepped aside in 2007 in support of his wife, Cristina Fernández, who was elected president. He participated in the unsuccessful Operation Emmanuel to release FARC hostages, and was narrowly defeated in the 2009 midterm election for deputy of Buenos Aires Province. Kirchner was appointed Secretary General of UNASUR in 2010. He and his wife were involved (either directly or through their close aides) in the 2013 political scandal known as the Route of the K-Money. Kirchner died of cardiac arrest on October 27, 2010, and received a state funeral.

Early life

Néstor Carlos Kirchner was born on February 25, 1950, in Río Gallegos, Santa Cruz, a Federal territory at the time. His father, Néstor Carlos Kirchner Sr., met the Chilean María Juana Ostoić by telegraphy. They had three children: Néstor, Alicia, and María Cristina. Néstor was part of the third generation of Kirchners living in the city. As a result of pertussis, he developed strabismus at an early age; however, he refused medical treatment because he considered his eye part of his self-image.[1] When Kirchner was in high school he briefly considered becoming a teacher, but poor diction hampered him;[2] he was also unsuccessful at basketball.[1]

Kirchner moved to La Plata in 1969 to study law at the National University. There was heated political controversy at the time, caused by the decline of the Argentine Revolution, the return of former president Juan Perón from exile, the election of Héctor Cámpora as president, and the beginning of the Dirty War. Kirchner joined the University Federation for the National Revolution (FURN), a political student group. Although it was described by some former members as a chapter of the Montoneros, others maintained that FURN was sympathetic and linked to Montoneros but was never involved with its attacks.[3] Kirchner was not a leader of the group.[3] He was present at the Ezeiza massacre, a celebration of Perón's return at Ezeiza International Airport which turned into a sniper shooting,[4] and the expulsion of Montoneros from Plaza de Mayo.[4] Although Kirchner met many members of the Montoneros, he was not a member of the group.[5] By the time the Montoneros were outlawed by Perón, he had left FURN.[6]

Kirchner met Cristina Fernández, three years his junior. The political turmoil made their romance short (six months) before they were married. At the civil ceremony, Kirchner's friends sang the Peronist song "Los muchachos peronistas". He graduated a year later, returned to Patagonia with Cristina,[3] and established a law firm with fellow attorney Domingo Ortiz de Zarate. Cristina joined the firm in 1979.[7] They worked for banks and financial groups which filed foreclosures, since the Central Bank's 1050 ruling had raised mortgage loan interest rates.[7] The Kirchners acquired 21 real-estate lots for a low price when they were about to be auctioned.[8] Although forced disappearances were common during the Dirty War, the Kirchners never signed a habeas corpus;[9] however, their law firm accepted military personnel involved in the Dirty War as clients.[10]

The National Reorganization Process eventually allowed political activity in preparation for a return to democracy. Kirchner founded the Ateneo Juan Domingo Perón organization, which supported deposed president Isabel Martínez de Perón and promoted political dialogue with the military.[8] Raúl Alfonsín, who was running for president for the Radical Civic Union (UCR), denounced an agreement between the military and the Peronist unions which sought an amnesty for the military. Kirchner organized a rally for Rodolfo Ponce, a union leader mentioned by Alfonsín.[8] Alfonsín won the 1983 presidential election, and Peronist Arturo Puricelli was elected governor of Santa Cruz. Puricelli appointed Kirchner president of the provincial social-welfare fund.[8]

Kirchner became known in the province by his 1984 resignation. He ran for mayor of Río Gallegos in 1987, and won by the slim margin of 110 votes. Kirchner's friend, Rudy Ulloa Igor, helped him to victory.[11] Julio de Vido and Carlos Zannini began working with him at this time. Kirchner used the state-owned media to promote his activities. The Peronist Ricardo del Val was elected governor that year, and the province was impacted by inflation in 1989. Kirchner became the main opponent of del Val, who was impeached and removed from office in 1990.[11][12]

Governor of Santa Cruz

Kirchner ran for governor of Santa Cruz in 1991. Although he received only 30 percent of the vote, he was elected due to the Ley de Lemas.[11] When Kirchner took office, Santa Cruz was experiencing an economic crisis, with high unemployment and a budget deficit equal to US$1.2 billion.[13] He expanded the number of provincial Supreme Court justices from three members to five and appointed three judges loyal to him; this gave him control of the provincial judiciary.[14][15] Kirchner was criticized for preventing the investigation of corruption cases.[15] Santa Cruz received $535 million in oil royalties in 1993, which Kirchner deposited in a foreign bank later absorbed by Morgan Stanley.[16] He was elected to the Constituent Assembly which drafted the 1994 amendment of the Argentine Constitution proposed by the Peronist president Carlos Menem. Although Kirchner opposed the clause allowing the reelection of the president, he could not prevent its approval. He proposed an amendment to the provincial constitution authorizing indefinite reelection of the governor.[17] Menem and Kirchner were reelected to their respective offices in 1995. Kirchner established a faction in the Justicialist Party (PJ) opposing Menem's economic policies of Menem, but Eduardo Duhalde, governor of the populous Buenos Aires province, opposed them.[17]

The number of state workers grew from 12,000 to 70,000 during Kirchner's administration. The province did not generate private-sector jobs, and private companies were driven away. A local journalist interviewed by journalist Jorge Lanata said that this placed de facto restrictions on economic freedom and allowed Kirchner to control the population. Most available jobs were in public works.[18]

With Menem unable to run for a third presidential term, Duhalde ran for president in 1999. Kirchner sided with Duhalde in his dispute with Menem, and sought reelection as governor of Santa Cruz. The PJ was defeated on the national level by the radical Fernando de la Rúa, who became president. Kirchner was reelected, despite the growth of the UCR in the province.[19] Troubled by economic crisis, De la Rúa resigned two years later during the December 2001 riots. The Congress appointed Adolfo Rodríguez Saá, governor of San Luis, as interim president. When Rodríguez Saá also resigned, Duhalde was appointed president. He slowly restored the economy, and hastened the presidential election when two piqueteros were killed during a demonstration.[20] However, the provincial elections were held on their original dates.[21]

2003 presidential election

Carlos Menem originally ran for a new term as president, and Eduardo Duhalde tried to prevent it. Instead of holding primary elections in the PJ, the 2003 elections used a variant of the Ley de Lemas.[22] The Peronist candidates were allowed to run in the general election, using political parties created for the event. Although Kirchner ran for president with Duhalde's support, he was not the president's first choice. Trying to prevent a third term for Menem, Duhalde approached Santa Fe governor Carlos Reutemann and Córdoba governor José Manuel de la Sota; Reutemann declined, and de la Sota was insufficiently popular. He also unsuccessfully approached Mauricio Macri, Adolfo Rodríguez Saá, Felipe Solá, and Roberto Lavagna. Duhalde initially resisted supporting Kirchner, fearing that he would ignore the former president if elected.[23] Since Kirchner was identified with the centre-left, Duhalde appointed the centre-right Daniel Scioli as his vice-presidential candidate.[24] Only a handful of Peronist governors supported either candidate; most remained neutral, awaiting the election to forge a relationship with the victor.[25]

The general election was held on April 27. Menem won the first round with 24.5 percent of the vote, followed by Kirchner with 22.2 percent. The conservative Ricardo López Murphy finished third, distanced by the two main candidates.[26] Since Menem was well short of the threshold required to win, a runoff election was scheduled for May 18. He had a negative public image, and polls showed Kirchner receiving 60 to 70 percent of the vote. To avoid a humiliating defeat, Menem pulled out of the runoff in a move criticized by the other candidates.[15][27] The judiciary declined requests for a new election and refused to sanction a runoff election between Kirchner and López Murphy, although López Murphy said he would not participate. The election was validated by the Congress, and Kirchner became president on May 25, 2003. Kirchner's 22.2 percent is the lowest vote percentage ever recorded for an Argentine president in a free election.[28]

Local elections were held in October. The mayor of Buenos Aires, Aníbal Ibarra, was reelected in a runoff against Mauricio Macri. Neither were Peronists, but Ibarra supported Kirchner and Macri was supported by Duhalde. Duhalde remained an influential figure in the Buenos Aires province; his ally Felipe Solá was elected governor by a landslide, and the PJ received its highest number of deputies since 1983 and won mayoral elections in several cities lost to the UCR in 1999. The three leading candidates in the Buenos Aires province were all Peronists. Victories in the other provinces gave the PJ control of the Congress, and three-quarters of Argentina's governors were Peronists. According to journalist Mariano Grondona, the Argentine government had become a dominant-party system.[29]

Presidency

First days

Kirchner took office as president of Argentina on May 25, 2003. Contrary to tradition, the ceremony was held at the Palace of the Argentine National Congress rather than Casa Rosada. He announced that he would spearhead change on many issues, from politics to culture. The ceremony was attended by the provincial governors, Supreme Court president Julio Nazareno, the heads of the armed forces, and Cuban leader Fidel Castro. Raúl Alfonsín was the only former president in attendance. Kirchner walked to the Casa Rosada along Avenida de Mayo, breaking with protocol to get close to the people, and was accidentally hit in the head with a camera.[30]

As he was elected with a small percentage of the vote, Kirchner sought to increase his political clout and public image.[22] He sought political allies in all political parties, not just the PJ. The Radicales K supported him from within the UCR. This policy was known as "Transversalism".[31] Striking an "anti-establishment image",[32] Kirchner set about creating "a sense of political renewal" in Argentina, despite the fact that many of his government associates came from the traditional political class.[33] He retained four members of Duhalde's cabinet. Economy Minister Roberto Lavagna, credited with the economic recovery, was kept to ensure that Kirchner maintained the economic policies laid down during the previous administration.[34] Ginés González García stayed as Minister of Health. Anibal Fernandez was moved to the Ministry of the Interior and José Pampuro to the Defense Ministry.[35] Kirchner brought in four members of his cabinet as governor of Santa Cruz. Alberto Fernández, who organized his political campaign, was appointed chief of the cabinet of ministers. Sergio Acevedo was placed in charge of intelligence. Julio de Vido was appointed Minister of Federal Planning, an office similar to his provincial one. Since the appointment of relatives was not unusual in Argentina, Kirchner's appointment of his sister Alicia as Minister of Social Development was uncontroversial.[34] Chancellor Rafael Bielsa was from another political party, FREPASO.[36]

Relations with the judiciary

The Argentine judiciary was unpopular since the presidency of Carlos Menem, most of whose judicial appointments were based on loyalty; his judiciary was known as the "automatic majority".[37] Kirchner sought to remove the most-controversial judges and organized the impeachment against Supreme Court president Julio Nazareno, who chose to resign.[37] Judge Adolfo Vázquez also resigned before impeachment, citing personal reasons.[38] Judges Eduardo Moline O'Connor and Guillermo López also resigned under similar circumstances.[37][39] The vacancies were well received by the public, boosting Kirchner's popularity.[37]

He arranged for judges to be publicized and evaluated before their proposal to the Congress. Raúl Zaffaroni, a former FREPASO politician, was the first judicial appointment under the new system.[40] He was followed by Elena Highton de Nolasco, the first woman appointed to the Supreme Court.[41] The appointment of Carmen Argibay (another female judge) was controversial, since Argibay was an atheist and a supporter of legal abortion.[42] The judges held liberal views on criminal justice, countering social demands for harsher, pro-victim policies after the murder of Axel Blumberg.[43] However, the new Supreme Court had little political power, as the national government ignored all rulings that were not favorable.[44]

Economic policy

Kirchner retained Duhalde's Minister of Economy, Roberto Lavagna, and his main economic policies. The pillars of the economic plan were trade and fiscal budget surpluses and a high exchange rate for the dollar. The surplus was aided by taxes levied during de la Rúa's presidency and the devaluation which occurred during the Duhalde administration.[45] Kirchner sought to rebuild the Argentine industrial base, public works and public services, renegotiating the operation of public services privatized by Carlos Menem and owned by foreign companies. His policies were accompanied by a nationalist rhetoric sympathetic to the poor.[46] However, almost a 25% of the country, from 8 to 10 millions of people, were still living in poverty during all of kirchnerism, despite of the financial prosperity.[47]

Kirchner and Lavagna negotiated a swap of defaulted debt in 2005, a write-down to one-third of the original debt.[48] Kirchner refused a structural adjustment program,[49] and making a single payment to the IMF with Central Bank reserves.[50] Although the economy grew at an eight-percent annual rate during Kirchner's term, much of its growth was due to favorable international conditions rather than Argentine policies. Argentina was benefited by the increase of the international price of soybean and other foods.[51] Foreign investment remained low because of hostility towards the IMF, the US and the United Kingdom, the re-nationalization of privatized companies (such as the water supply, managed by the French company Suez),[52] diplomatic isolation and state interventionism. The energy sector suffered, lack of investment reduced energy reserves during the 2000s.[48]

Lavagna proposed to slow economic growth and control inflation. Kirchner rejected this, promoting wage increases to reduce economic inequality[53] and extending unemployment insurance and other types of social welfare.[54] Public services such as public transportation, electricity, gas and water supply were subsidied and kept at low prices. Food industries were subsidied as well. The subsidies eventually expanded to several uncommon areas. This increased the economic activity, but also increased inflation and reduced the private investment in those areas.[55] Unable to control inflation, the government influenced the National Institute of Statistics and Census of Argentina, which under-reported it, as well as poverty (which was calculated with the inflation figures).[56] The superpowers law, sanctioned during the crisis, was prorrogated and eventually made permanent in 2006; this law allowed the president to rearrange the budget with supervision from the Congress.[57] Kirchner sought to win over the Argentine Workers' Central Union and leaders of more moderate piquetero factions to reduce the chances of strikes and protests.[58][56] He nevertheless continued to oppose hard-line elements of the piquetero movement, such as that of Raúl Castells.[59] Kirchner's policy helped to fragment the piqueteros, with some declaring their allegiance to him and others continuing to oppose him.[59] Their usual system of protest (blocking streets) made them highly unpopular. However, Kirchner refused to suppress the piquetero demonstrations to avoid the risk of further violence.[60]

Lavagna refused to be a candidate in the 2005 midterm elections, and criticized the overpricing of public works managed by Minister of Federal Planning Julio de Vido. As a result, Kirchner asked Lavagna to resign. Finance secretary Guillermo Nielsen, who managed the debt restructuring, also resigned. Felisa Miceli, head of Banco de la Nación Argentina, replaced Lavagna as Minister of Economy.[61] Miceli resigned in 2007, months before the presidential elections, because of a scandal over a bag with a large amount of money which was found in her office bathroom. She was replaced by Secretary of Industry Miguel Gustavo Peirano.[62]

Foreign policy

Kirchner took a pragmatic approach to Argentine foreign policy,[63] and Argentina–United States relations did not continue the parallel track of the 1990s. Chancellor Rafael Bielsa called the relationship between the countries "cooperation without cohabitation" in contrast to that of the Menem era, which was known as "carnal relations".[64] Kirchner opposed the proposed Free Trade Area of the Americas. The 4th Summit of the Americas, hosted in Mar del Plata, ended with violent protests against U.S. President George W. Bush; negotiations stalled, and the FTAA was not implemented.[65] Kirchner told the United Nations that, although he opposed terrorism, he did not support the War on Terror.[66] He refused to receive U.S. Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld, and sent forces to the United Nations Stabilisation Mission in Haiti.[67]

Kirchner sought increased integration with other Latin American countries. He revived and tried to increase the Mercosur trade bloc and improved relations with Brazil[68] (without automatically aligning with that country, the regional power of South America).[69] The president tried to keep a middle ground between Brazil, since he considered Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva too conservative, and Venezuela (considering Hugo Chávez too anti-American). Kirchner worked with Brazilian centre-left president Lula and Chilean Ricardo Lagos and the left-wing rulers Chávez, Fidel Castro and Evo Morales of Bolivia.[67] He established a political alliance with Chávez's government,[70] and by 2008, Argentinian exports to Venezuela were quadruple what they were in 2002.[71] A bilateral military commission was established with Venezuela, through which some technological exchange took place.[72]

2005 midterm elections

Kirchner soon distanced himself from Duhalde, removing those close to the former president from the government to reduce his political influence. He also sought supporters across the social and political spectrum to counter Duhalde's influence in the party. Although Duhalde was not initially against Duhalde, the PJ is a party that rallies under a single leader, and Kirchner tried to prevent the presence of alternative leaderships in it.[73] However, they put their differences behind them during the October 2003 legislative elections.[74] Their dispute was fanned by the political weight of Buenos Aires province (the most populous in Argentina, with almost 40 percent of the national vote),[75] and continued through the 2005 midterm elections. Without consensus in the PJ for a candidate for senator in the Buenos Aires province, both leaders had their wives run for office: Hilda González de Duhalde for the PJ and Cristina Fernández de Kirchner for the Front for Victory (the Kirchners' party).[76] Cristina Kirchner won the election.[77] As in 2003, the elections were defined by Peronist factions; the opposition parties could not put up a united national front.[78] The victory gave Kirchner the confidence to remove Lavagna, Rafael Bielsa, Jose Pampuro, and Alicia Kirchner from his cabinet.[53]

Human rights policy

Kirchner operated on the premise that the Dirty War continued, albeit in a different manner.[69] In his inaugural speech, he supported human rights organizations which sought the incarceration of the military connected with the National Reorganization Process.[79] He also ordered the top military leadership to retire.[80] Kirchner sent a bill to the Congress to annul the full stop law and the Law of Due Obedience, which had halted trials of the military for crimes related to the Dirty War. The laws had been repealed in 1998, but that repeal had little legal significance, as only an annulment would reopen the cases.[81] Although this initiative was opposed by Duhalde and Scioli, most legislators considered it a symbolic gesture since the laws' constitutionality would be decided by the Supreme Court.[82] Both laws were annulled by the Congress in August 2003, and many cases were reopened as a result. The Supreme Court declared the laws, and Menem's presidential pardons, unconstitutional in 2005.[83][84] Jorge Julio López, witness in a trial of police officer Miguel Etchecolatz, disappeared in 2006.[85]

Kirchner also changed the extradition policy, allowing it for prosecuted people not facing charges in the country. He also supported the requests by human rights organizations to turn the former detention centers into memorial for the disappeared. Argentina became a signatory of the UN Convention on the Non-Applicability of Statutory Limitations to War Crimes and Crimes Against Humanity in 2003.[81] A creative interpretation of the convention by the courts allowed to skip the statutory limitations to crimes committed decades in the past, and also the ex post facto applicability of laws that were not in force at the time of the crimes.[86]

The Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo held their final demonstration in 2006, believing that Kirchner (unlike the previous presidents) was not their enemy.[87] They became political allies of Kirchner, who placed them in prominent locations during his speeches, and the group became a powerful NGO.[88] He further underscored civilian control over the military by appointing Nilda Garré — who had been a political prisoner during the Dirty War — to be the country's first woman Minister of Defense.[89] As a result of his policies and approach, tensions between the civilian authorities and the military remained tense throughout Kirchner's presidency.[89]

Although Kirchner repudiated the military forces who participated in the Dirty War, he overlooked the guerrilla movements of the time. The government ignored the 30th anniversary of the ERP attack on the tank regiment in Azul and the 15th anniversary of the 1989 attack on La Tablada barracks. According to Rosendo Fraga, Kirchner downplayed the presence of terrorist organizations during the Dirty War.[90] Guerrillas who committed suicide or who were executed by their own organizations were re-categorized in 2006 as victims of state terrorism, and their survivors were compensated by the state.[91] However, victims of the guerrillas were not compensated.[91] Journalist Ceferino Reato said that the Kirchners sought to replace the theory of the two demons (which blamed the Dirty War on the military and the guerrillas) with a "theory of angels and demons", which blamed only the military.[92][93]

After the presidency

With Cristina Fernández de Kirchner's election as president, Kirchner became First Gentleman.[94] He remained highly influential during his wife's term,[95] supervising the economy and leading the PJ.[96] Their marriage has been compared with those of Juan and Eva Perón and Bill and Hillary Clinton.[94] Media observers suspected that Kirchner stepped down as president to circumvent the term limit, swapping roles with his wife.[94][96][97]

He participated in Operation Emmanuel in Colombia to release a group of FARC hostages, including Colombian politician Íngrid Betancourt, in December 2007.[98] Kirchner returned to Argentina after negotiations failed.[99] The hostages were freed a year later during Operation Jaque, a covert operation by the Colombian military.[100]

Kirchner played an active role in the 2008 government conflict with the agricultural sector. At that time, he became president of the Justicialist Party and publicly supported Cristina Fernández de Kirchner in the conflict;[101] Kirchner accused the agricultural sector of attempting a coup d'état.[102] He spoke in support of a bill before the Congress at a demonstration at the Palace of the Argentine National Congress.[103] Many senators who had supported the government proposal rejected it, and the voting was tied 36–36. Vice-President Julio Cobos, president of the Chamber of Senators, cast the decisive vote in opposition to the measure.[104]

In the June 2009 legislative elections, Kirchner was defeated by Francisco de Narváez of the Union PRO coalition for National Deputy of Buenos Aires Province. The Front for Victory was defeated in the Buenos Aires, Santa Fe and Córdoba, and the Kirchners lost the Congressional majority. Voter disenchantment with the Kirchners was caused by inflation, crime and the previous year's agricultural conflict, which cost them rural support.[105] The Kirchners pushed a media law through during the Congress' lame-duck session.[106]

Kirchner was nominated by Ecuador for Secretary General of the Union of South American Nations (UNASUR), but was rejected by Uruguay when Uruguay and Argentina were involved in a pulp-mill dispute. The dispute was resolved in 2010; new Uruguayan president José Mujica supported Kirchner, who was unanimously elected UNASUR's first secretary-general at a member-state summit in Buenos Aires on 4 May.[107] Kirchner successfully mediated the 2010 Colombia–Venezuela diplomatic crisis.[108]

Style and ideology

.jpg)

| Part of a series on |

| Populism |

|---|

|

People

|

|

Related topics |

|

Kirchner was often labelled a left-wing and progressive president,[109][110] with the cultural critic Alejandro Kaufman stating that Kirchner was "an Argentine social democrat: a centre-left Peronist",[111] who had been elected on a "moderate-progressive" platform.[112] However, that assessment is relative.[113] Although he was left of previous Argentine presidents from Raúl Alfonsín to Eduardo Duhalde and contemporary Brazilian president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, he was right of other Latin American presidents such as Hugo Chávez and Fidel Castro.[113] Kirchner's nationalist approach to the Falkland Islands sovereignty dispute was closer to the right,[114] and he did not consider left-wing policies such as the socialization of production or the nationalization of public services which were privatized during the Menem presidency.[114] He did not attempt to modify church–state relations or reduce the armed forces.[114] Kirchner's economic views were influenced by the government of Santa Cruz: a province rich in oil, gas, fish and tourism, which focused on the primary sector.[69] Usually avoiding long-term policies, he moved left or right according to circumstances.[64] Many leftist activists in Argentina were cynical about the sincerity of his commitment to progressive ideals and to aiding the country's underclass.[115]

A Peronist, Kirchner handled political power as Peronist leaders have traditionally done.[79] He nevertheless sought to portray himself as being different from previous Peronist leaders.[116] The generation of controversy with other political or social forces and the polarization of public opinion characterized his political style.[117] This strategy was used against the financial sector, the military and police, foreign countries, international bodies, newspapers, and Duhalde himself with varying degrees of success.[118] Kirchner sought to generate an image contrasting with those of former presidents Carlos Menem and Fernando de la Rúa. Menem was seen as frivolous and De la Rúa as doubtful, so Kirchner tried to be seen as serious and determined.[119]

He sought to concentrate political power, and the emergency superpowers law giving discretionary powers to the president to change the national budget was periodically renewed. The Front for Victory (conceived as a lema of the PJ) became a political alliance of the PJ, pro-Kirchner factions in other parties, and minor left-wing parties. The progressivist population, lacking leadership since the crisis which discredited the UCR, also supported the new coalition.[22] Most Peronists simply defected to the new party, and the end of the economic crisis and the discretionary control of state finances allowed Kirchner to discipline his allies and co-opt his rivals. As a consequence, the Congress became compliant and the opposition was unable to present a credible alternative to the government. In addition to concentrating power, Kirchner micromanaged most government tasks or assigned them to trusted aides regardless of cabinet hierarchy. He managed relations with the United States and Brazil, leaving relations with Bolivia and Venezuela in the hands of Minister of Federal Planning Julio de Vido.[64] There were no cabinet meetings during Kirchner's presidency, rare in a national government; this may have been influenced by his governance of Santa Cruz, a sparsely-populated province in which the cabinet was of little use and decisions were primarily made by the governor.[120]

Allegations of embezzlement

The Skanska case occurred during Kirchner's presidency. Several members of de Vido's ministry were accused of bribery in requests for tender for pipeline construction, based on a tape recording of Skanska employees discussing the bribes. The case was closed in 2011, when it was ruled that the tape was not acceptable evidence and there was no overpricing. It was reopened in 2016 (with Cristina Kirchner out of the government), and the tape was accepted as evidence.[121]

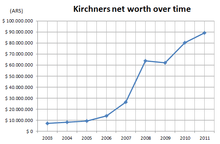

The Kirchners' net worth, as reported to the AFIP, increased by 4,500 percent between 1995 and 2010.[122] A substantial increase occurred in 2008, from 26.5 million to 63.5 million Argentine pesos, due to the sale of long-owned land, hotel rentals, and time deposits in Argentine pesos and US dollars. They founded a business-consulting company, El Chapel and established the Hotesur SA and Los Sauces firms to manage their luxury hotels in El Calafate. The Kirchners expanded Comasa, a firm of which they had a 90-percent ownership. Their salaries as politicians were 3.62 percent of their total earnings.[123]

Kirchner was tried for unjust enrichment in 2004, with the case focusing on the increase in his wealth from 1995 to 2003. It was first heard by judge Juan José Galeano and moved to judge Julián Ercolini, who acquitted him in 2005.[124] A new case involving both Kirchners was heard by judge Norberto Oyarbide, who acquitted them in 2010.[125]

The TV program Periodismo para todos aired an investigation in 2013, detailing a case of embezzlement and an associated money trail involving the Kirchners and businessman Lázaro Báez. Báez received 95 percent of the requests for tender in Santa Cruz province since 2003, more than four billion pesos,[126] and the scandal was known as the Route of the K-Money (Spanish: La ruta del dinero K). In the 2014 Hotesur scandal, a company owned by Báez rented more than 1,100 rooms per month at Kirchner family hotels even when they were unoccupied. A money-laundering scheme was suspected, funnelling public-works money to the Kirchner family.[127]

In April 2016, Kirchner's secretary and confidant Daniel Muñoz (who died early that year) was identified in the Panama Papers as owner of real-estate investment firm Gold Black Limited. Company director Sergio Todisco was investigated by prosecutors who suspected that the company was used for money laundering.[128]

Death

Kirchner died on October 27, 2010, at age 60. It was a national holiday for the INDEC to run a national census, so he was at home in El Calafate. After a cardiac arrest, Kirchner was rushed to a local hospital and was pronounced dead at 9:15 a.m.[96] He had undergone two medical procedures that year: surgery on his right carotid artery in February[129] and an angioplasty in September.[130] His death was a surprise for the Argentinian population, to whom he had always played down his heart problems.[131]

His body was flown to the Casa Rosada for a state funeral, and three national days of mourning were declared. Kirchner's funeral was attended by thousands, despite heavy rain. According to media reports, 1,000 people per hour entered the Casa Rosada in groups of 100 to 150. Cristina Kirchner, dressed in mourning, stood next to the coffin. People brought candles, flags and flowers, some of which Cristina accepted personally.[97]

Kirchner's death evoked international reaction moments after it was announced, with Brazil and Venezuela also declaring three national days of mourning. Colombian President Juan Manuel Santos and the Organization of American States declared a moment of silence, and U.S. president Barack Obama sent condolences.[130] Attendees at Kirchner's funeral included Chávez and Lula da Silva.[97]

Legacy

Although the health problems of Kirchner were known, his death was completely unexpected, and had a great impact on the politics of Argentina. Kirchner died at an early age, while still being a highly influential figure in politics, despite of not being president at the time. Presidents Manuel Quintana, Roque Sáenz Peña and Roberto María Ortiz died in office, but none of them had a political clout comparable to that of Kirchner. President Juan Perón had a similar power and died in office, but his death was not unexpected, as he had already reached the life expectancy of the time. Other figures of the history of Argentina who achieved great political clout, such as José de San Martín, Juan Manuel de Rosas, Julio Argentino Roca, Carlos Pellegrini and Hipólito Yrigoyen, all died when they were already retired from politics, or even abroad.[132]

The Relato K built a cult of personality on the figure of Kirchner. The president Cristina Kirchner avoided to reference him by name, and talked instead about "He" or "Him", with emphasis on the pronoun and with a universally capitalized form. As in the English language, in the Spanish language this figure of speech is usually reserved to make reference to God.[133] Kirchner is also compared with San Martín, in an attempt to raise him to a similar national hero status. This comparison was included, for instance, in an official video by the ministry of social welfare.[134] A month after his death many districts named streets, schools, neighbourhoods, institutions and places as "Néstor Kirchner". Some noteworthy examples are the Néstor Kirchner Cultural Centre (formerly "Bicentennial Cultural Centre") and the second leg of the 2010–11 Argentine Primera División season. The change proved controversial in some cities, such as Caleta Olivia, where the renamed street was formerly named after the Falklands War veterans.[135] A bill was rejected in Apóstoles, Misiones.[135] No bill was even considered in Buenos Aires, as a previous law only allows to name streets after people who have died at least a decade before.[135] The presidency of Mauricio Macri proposed a bill in 2016 to forbid any public places or institutions to be named after people unless they died at least two decades before.[136]

References

Citations

- 1 2 Alberto Amato (October 28, 2010). "Un chico formado bajo los implacables vientos del sur" [A kid raised under the implacable winds of the south] (in Spanish). Clarín. Retrieved May 3, 2016.

- ↑ Majul, p. 17

- 1 2 3 Pablo Morosi (May 18, 2003). "Tiempos de militancia en La Plata Néstor Kirchner" [Times of militancy at La Plata Néstor Kirchner] (in Spanish). La Nación. Retrieved May 3, 2016.

- 1 2 Majul, p. 18

- ↑ "Kirchner aclaró que nunca fue montonero" [Kirchner clarified that he has never been Montonero] (in Spanish). Clarín. May 6, 2003. Retrieved May 3, 2016.

- ↑ Majul, p. 19

- 1 2 Mariela Arias (September 28, 2012). "Cómo fueron los "exitosos años" de Cristina Kirchner como abogada en Santa Cruz" [How were the "successful years" of Cristina Kirchner in Santa Cruz] (in Spanish). La Nación. Retrieved August 27, 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 Majul, p. 22

- ↑ "Los Kirchner no firmaron nunca un hábeas corpus" [The Kirchner never signed any habeas corpus] (in Spanish). La Nación. December 13, 2014. Retrieved May 3, 2016.

- ↑ Majul, p. 20

- 1 2 3 Majul, p. 23

- ↑ Lucía Salinas (September 24, 2014). "La historia de los días en que la Presidenta fue gobernadora" [The history of the days when the president was governor] (in Spanish). Clarin. Retrieved May 3, 2016.

- ↑ Epstein, p. 13

- ↑ Majul, p. 15

- 1 2 3 Uki Goñi (May 15, 2003). "Menem bows out of race for top job". The Guardian. Retrieved May 22, 2016.

- ↑ "Ex vice de Santa Cruz acusó a Kirchner de "robarse" los fondos" [Former vice gobernor of Santa Cruz accused Kirchner of "stealing" the funds] (in Spanish). Perfil. May 28, 2010. Retrieved May 16, 2016.

- 1 2 Martín Dinatale (April 28, 2003). "El patagónico que pegó el gran salto" [The patagonic that made the great jump] (in Spanish). La Nación. Retrieved May 16, 2016.

- ↑ Lanata, p. 41

- ↑ Nicolás Cassese (May 24, 1999). "Un antimenemista persistente" [A persistent antimenemist] (in Spanish). La Nación. Retrieved May 22, 2016.

- ↑ Pablo Morosi (June 26, 2003). "El piquete que cambió la Argentina" [The picket that changed Argentina] (in Spanish). La Nación. Retrieved April 29, 2016.

- ↑ Fraga, p. 26

- 1 2 3 Romero, p. 103

- ↑ Fraga, p. 19–20

- ↑ Fraga, pp. 21–23

- ↑ Fraga, p. 23

- ↑ Mariano Obarrio (April 28, 2003). "Menem y Kirchner disputarán la segunda vuelta el 18 de mayo" [Menem and Kirchner will go for a runoff election on May 18] (in Spanish). La Nación. Retrieved May 22, 2016.

- ↑ "Don't cry for Menem". The Economist. March 15, 2003. Retrieved September 18, 2015.

- ↑ Fraga, pp. 27–31

- ↑ Fraga, pp. 67–68

- ↑ Martín Rodríguez Yebra (May 26, 2003). "Kirchner asumió con un fuerte mensaje de cambio" [Kirchner took office with a strong message of change] (in Spanish). La Nación. Retrieved May 22, 2016.

- ↑ Romero, p. 105

- ↑ Petras & Veltmeyer 2016, p. 72.

- ↑ Kozloff 2008, p. 7.

- 1 2 Peter Greste (May 21, 2003). "New Argentine cabinet revealed". BBC. Retrieved May 22, 2016.

- ↑ "Argentina: Kirchner Names New Cabinet". Pravda. May 21, 2003. Retrieved May 22, 2016.

- ↑ Larry Rohter (May 21, 2003). "Argentine President-Elect Unveils a Diverse Cabinet". The New York Times. Retrieved May 22, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 "Argentine leader defies pessimism". Washington Times. July 21, 2003. Retrieved May 22, 2016.

- ↑ "Supreme Court Justice Resigns in Argentina". Merco Press. September 2, 2004. Retrieved May 22, 2016.

- ↑ Marcela Valente (October 23, 2003). "Third Justice on Corruption-Tainted Supreme Court Resigns". Inter Press Service. Retrieved May 22, 2016.

- ↑ Oliver Galak (August 10, 2003). "Zaffaroni, el juez que enciende la polémica" [Zaffaroni, the judge that ignites the controversy] (in Spanish). La Nación. Retrieved May 22, 2016.

- ↑ Newman, p. 12

- ↑ "Carmen Argibay". The Times. June 8, 2014. Retrieved May 22, 2016.

- ↑ Fraga, p. 83

- ↑ Romero, p. 115

- ↑ Eduardo Levy Yeyati (August 23, 2011). "Pasado y futuro del modelo" [Past and future of the model] (in Spanish). La Nación. Retrieved May 22, 2016.

- ↑ Mosley, p. 263

- ↑ Romero, p. 110

- 1 2 Hedges, p. 283

- ↑ Romero, p. 102

- ↑ Fraga, pp. 65–66

- ↑ Romero, p. 99

- ↑ "Argentina severs Suez water deal". BBC. March 21, 2006. Retrieved June 9, 2016.

- 1 2 "Argentina replaces economy boss". BBC. November 29, 2005. Retrieved June 9, 2016.

- ↑ Fraga, p. 62

- ↑ Romero, p. 107

- 1 2 Hedges, p. 285

- ↑ Romero, p. 108

- ↑ Kozloff 2008, p. 74.

- 1 2 Kozloff 2008, p. 174.

- ↑ Fraga, pp. 59–63

- ↑ Adam Thomson and Richard Lapper (November 28, 2005). "Argentina ousts economy minister Lavagna". Financial Times. Retrieved June 9, 2016.

- ↑ Mark Oliver (July 17, 2007). "Minister resigns over bag of cash in bathroom". The Guardian. Retrieved June 9, 2016.

- ↑ Fraga, p. 36

- 1 2 3 Dominguez, p. 104

- ↑ Larry Rohter and Elisabeth Bumiller (November 5, 2005). "Hemisphere Summit Marred by Violent Anti-Bush Protests". The New York Times. Retrieved June 12, 2016.

- ↑ "Argentina's Kirchner Calls at UN for "New Financial Architecture"" (in Spanish). Executive Intelligence Review. September 29, 2006. Retrieved September 1, 2013.

- 1 2 Fraga, p. 125

- ↑ Worldpress.org. September 2003. "Kirchner Reorients Foreign Policy". Translated from article in La Nación, 15 June 2006.

- 1 2 3 Fraga, p. 37

- ↑ Kozloff 2008, pp. 13, 41.

- ↑ Kozloff 2008, p. 41.

- ↑ Kozloff 2008, p. 90.

- ↑ Romero, p. 106

- ↑ Fraga, pp. 55–58

- ↑ Fraga, p. 57

- ↑ "Fracasó la negociación entre Kirchner y Duhalde" [The negotiations between Kirchner and Duhalde failed] (in Spanish). La Nación. July 1, 2005. Retrieved May 3, 2016.

- ↑ Ramón Indart (December 25, 2009). "El PJ bonaerense se resquebraja por la pelea Duhalde - Kirchner" [The PJ in Buenos Aires gets fragmented by the Duhalde - Kirchner conflict] (in Spanish). Perfil. Retrieved May 3, 2016.

- ↑ Fraga, p. 133–135

- 1 2 Fraga, p. 38

- ↑ Lessa, p. 114

- 1 2 Lessa, p. 115

- ↑ Fraga, p. 59–60

- ↑ "Argentine amnesty laws scrapped". bbc. June 15, 2005. Retrieved June 28, 2016.

- ↑ "Argentine court overturns "Dirty War" pardon". Reuters. April 25, 2007. Retrieved June 28, 2016.

- ↑ "Argentines march one year after disappearance". Reuters. September 18, 2007. Retrieved June 28, 2016.

- ↑ Lessa, p. 116

- ↑ "Las Madres de Plaza de Mayo organizan su última marcha" [The mothers of Plaza de Mayo organize their last march] (in Spanish). La Nación. January 25, 2006. Retrieved June 28, 2016.

- ↑ Annie Kelly (June 12, 2011). "Scandal hits Argentina's mothers of the disappeared". The Guardian. Retrieved June 28, 2016.

- 1 2 Kozloff 2008, p. 83.

- ↑ Fraga, p. 72

- 1 2 Mariano De Vedia (September 5, 2011). "Polémica por una lista de indemnizaciones" [Controversy over a list of indemnities] (in Spanish). La Nación. Retrieved June 29, 2016.

- ↑ Ceferino Reato (January 20, 2014). "Gelman: ni dos demonios, ni ángeles y demonios" [Gelman: neither two demons, nor angels and demons] (in Spanish). La Nación. Retrieved June 29, 2016.

- ↑ Reato, pp. 353–358

- 1 2 3 Kevin Gray (December 7, 2007). "Argentina's Kirchner to become "first gentleman"". Reuters. Retrieved June 12, 2016.

- ↑ Daniel Schweimler (June 18, 2008). "Argentina's farm row turns to crisis". BBC. Retrieved June 12, 2016.

- 1 2 3 Alexei Barrionuevo (October 27, 2010). "Argentine Ex-Leader Dies; Political Impact Is Murky". The New York Times. Retrieved June 12, 2016.

- 1 2 3 "Argentina ex-leader Kirchner to be buried". BBC. October 29, 2010. Retrieved June 12, 2016.

- ↑ "Chavez launches hostage mission". BBC. December 29, 2007. Retrieved June 12, 2016.

- ↑ Jaime Rosemberg (January 2, 2008). "Tras fracasar el rescate de los tres rehenes, volvió Kirchner" [Kirchner returned after the failure to liberate three hostages] (in Spanish). La Nación. Retrieved June 12, 2016.

- ↑ Tim Padgett (July 2, 2008). "Colombia's Stunning Hostage Rescue". Time. Retrieved June 12, 2016.

- ↑ "Contraataque de Kirchner: sumará al PJ a la pelea" [Kirchner's counter-attack: he will make the PJ join the fight] (in Spanish). La Nación. May 27, 2008. Retrieved June 12, 2016.

- ↑ "El PJ acusó al campo de agorero y golpista y respaldó a Cristina" [The PJ accused the countryside of rebellion and supported Cristina] (in Spanish). La Nación. May 27, 2008. Retrieved June 12, 2016.

- ↑ "Kirchner reforzó los ataques al campo en su última apuesta antes del debate" [Kirchner insisted on his attacks to the contryside in his last bet before the debate] (in Spanish). La Nación. July 15, 2008. Retrieved June 12, 2016.

- ↑ "Argentine Senate rejects farm tax". BBC. July 17, 2008. Retrieved June 12, 2016.

- ↑ Rory Carroll (June 30, 2009). "Argentina's Kirchners lose political ground in mid-term elections". The Guardian. Retrieved June 12, 2016.

- ↑ Gustavo Ybarra (September 11, 2009). "Unión opositora contra la ley de medios" [Opposition unity against the media law] (in Spanish). La Nación. Retrieved June 12, 2016.

- ↑ "Kirchner to head Americas bloc". Al Jazeera. 5 May 2010. Retrieved 28 October 2010.

- ↑ "Chávez, Santos restore bilateral relations with help of Kirchner". Buenos Aires Herald. August 10, 2010. Retrieved June 12, 2016.

- ↑ Petras & Veltmeyer 2016, p. 60.

- ↑ BBC News. 18 April 2006. Analysis: Latin America's new left axis.

- ↑ Kaufman 2011, p. 103.

- ↑ Kaufman 2011, p. 97.

- 1 2 Fraga, p. 33

- 1 2 3 Fraga, p. 34

- ↑ Kozloff 2008, pp. 181, 182.

- ↑ Kozloff 2008, p. 181.

- ↑ Fraga, p. 40

- ↑ Fraga, pp. 40–41

- ↑ Fraga, p. 52

- ↑ Fraga, p. 95

- ↑ "Reabren el caso Skanska y De Vido vuelve a quedar en la mira de la Justicia" [The Skanska case is reopened and De Vido is once again aimed by the judiciary] (in Spanish). Perfil. April 13, 2016. Retrieved July 16, 2016.

- ↑ Lanata, p. 24

- ↑ Lanata, p. 26

- ↑ Lanata, p. 29

- ↑ Paz Rodríguez Niell (January 19, 2010). "Oyarbide sobreseyó a los Kirchner en la causa por enriquecimiento ilícito" [Oyarbide declared the Kirchners innocent in the case of unjust enrichment] (in Spanish). La Nación. Retrieved July 16, 2016.

- ↑ Lanata, p. 44

- ↑ Taos Turner (November 27, 2014). "Argentine Probe Sparks Dispute Between Government, Judiciary". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved July 18, 2016.

- ↑ Nicholas Nehamas and Kyra Gurney (July 16, 2016). "Argentina probes ties between ex-presidents, Miami real estate empire". Miami Herald. Retrieved July 18, 2016.

- ↑ "Ex-Argentina President Kirchner has artery operation". BBC. February 8, 2010. Retrieved June 12, 2016.

- 1 2 Arthur Brice (October 28, 2010). "Former Argentina President Kirchner dies suddenly". CNN. Retrieved June 12, 2016.

- ↑ Kaufman 2011, p. 101.

- ↑ Mendelevich, pp. 132–133

- ↑ Mendelevich, p. 132

- ↑ "Un video del Gobierno compara a Néstor Kirchner con San Martín: "Dos gigantes de la Historia"" [A government video compares Néstor Kirchner with San Martín: "Two giants of history"] (in Spanish). La Nación. February 25, 2014. Retrieved September 1, 2016.

- 1 2 3 "Néstor Kirchner, un nombre para calles, barrios y escuelas" [Néstor Kirchner, a name for streets, neighbourhoods and schools] (in Spanish). La Nación. November 17, 2010. Retrieved September 1, 2016.

- ↑ Maia Jastreblansky (October 9, 2016). "Buscan reemplazar el nombre de Kirchner de los lugares públicos" [They seek to remove the Kirchner name from public places] (in Spanish). La Nación. Retrieved October 11, 2016.

Bibliography

- Epstein, Edward (2006). Broken promises? The Argentine crisis and Argentine democracy. United Kingdom: Lexington Books. ISBN 978-0-7391-0928-1. Retrieved December 30, 2012.

- Fraga, Rosendo (2010). Fin de ciKlo (in Spanish). Buenos Aires: Ediciones B. ISBN 978-987-627-167-7.

- Hedges, Jill (2011). Argentina: A modern history. United States: I.B.Tauris. ISBN 978-1-84885-654-7. Retrieved November 27, 2013.

- Kaufman, Alejandro (2011). "What's in a Name: The Death and Legacy of Néstor Kirchner". Journal of Latin American Cultural Studies. 20 (1): 97–104. doi:10.1080/13569325.2011.562635.

- Kozloff, Nicholas (2008). Revolution!: South America and the Rise of the New Left. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-230-61754-4.

- Lanata, Jorge (2014). 10K (in Spanish). Argentina: Planeta. ISBN 978-950-49-3903-0.

- Lessa, Francesca (2012). Amnesty in the Age of Human Rights Accountability: Comparative and international perspectives. United States: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-02500-4.

- Majul, Luis (2009). El Dueño (PDF) (in Spanish). Argentina: Planeta. ISBN 978-950-49-2157-8.

- Mendelevich, Pablo (2013). El Relato Kirchnerista en 200 expresiones [The Kirchnerite speech in 200 words] (in Spanish). Argentina: Ediciones B. ISBN 978-987-627-412-8.

- Mosley, Paul. The Politics of Poverty Reduction. United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-969212-5.

- Newman, Graeme (2010). Crime and Punishment around the World. England: ABC-Clio. ISBN 978-0-313-35133-4.

- Petras, James; Veltmeyer, Henry (2016). What's Left in Latin America?: Regime Change in New Times. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-76162-3.

- Reato, Ceferino (2010). Operación Primicia: El ataque de Montoneros que provocó el golpe de 1976 (in Spanish). Buenos Aires: Sudamericana. ISBN 978-950-07-3254-3.

- Romero, Luis Alberto (2013). La larga crisis argentina [The long Argentine crisis]. Argentina: Siglo Veintiuno Editores. ISBN 978-987-629-304-4.

Further reading

- Wylde, Christopher (2011). "State, Society and Markets in Argentina: The Political Economy of Neodesarrollismo under Nestor Kirchner, 2003–2007". Bulletin of Latin American Research. 30 (4): 436–452.

- Wylde, Christopher (2014). "The developmental state is dead, long live the developmental regime! Interpreting Nestor Kirchner's Argentina 2003–2007". Journal of International Relations and Development. 17: 191–219.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Néstor Kirchner. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Néstor Kirchner |

| Spanish Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- (Spanish) Biography by CIDOB Foundation

- (Spanish) LA LÓGICA DICOTÓMICA EN NÉSTOR KIRCHNER: ANÁLISIS DE UN CASO

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by position created |

Secretary General of Unasur 2010 |

Succeeded by María Emma Mejía Vélez |

| Preceded by Eduardo Duhalde |

President of Argentina 2003–2007 |

Succeeded by Cristina Fernández de Kirchner |

| Preceded by Héctor Marcelino García |

Governor of Santa Cruz 1991–2003 |

Succeeded by Héctor Icazuriaga |

| Honorary titles | ||

| Preceded by Cristina Fernández de Kirchner |

First Gentleman of Argentina 2007–2010 |

Succeeded by Juliana Awada Macri |