Mushroom ketchup

_-_(cropped).jpg)

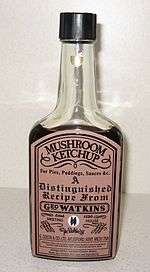

Mushroom ketchup is a style of ketchup (also spelled "catsup") that is prepared with mushrooms as its primary ingredient. Originally, ketchup in the United Kingdom was prepared with mushrooms as a primary ingredient, instead of tomato, the main ingredient in contemporary preparations. Historical preparations involved packing whole mushrooms into containers with salt. It is used as a condiment and may be used as an ingredient in the preparation of other sauces and other condiments. Several brands of mushroom ketchup were produced and marketed in the United Kingdom, some of which were exported to the United States, and Geo Watkins Mushroom Ketchup continues to exist in contemporary times as a commercially mass-produced product.

History

In the United Kingdom, ketchup was historically made with mushrooms as a primary ingredient.[1][2][3] The result was sometimes referred to as "mushroom ketchup".[1] In contemporary times, ketchup's primary ingredient is typically tomato.[4] Mushroom ketchup appears to have originated in Great Britain.[5] In the United States, mushroom ketchup dates back to at least 1770 in English-speaking colonies in North America.[5] A manuscript cookbook from Charleston, South Carolina that was written in 1770 by Harriott Pinckney Horry documented a mushroom ketchup that used two egg whites to clarify the mixture.[5] This manuscript also contained a recipe for walnut ketchup.[5] Richard Briggs's The English Art of Cookery, first published in 1788,[6] has recipes for both mushroom ketchup and walnut ketchup.[5]

Ingredients and preparation

The preparation of mushroom ketchup involved packing whole mushrooms into containers with salt, allowing time for the liquid from the mushrooms to fill the container, and then cooking them to a boiling point in an oven.[2] They were finished with spices such as mace, nutmeg and black pepper, and then the liquid was separated from solid matter by straining it.[2] Several species of edible mushrooms were used in its preparation.[1] Some versions used vinegar as an ingredient.[3] The final product had a dark color that was derived from the mushroom spores that transferred from the mushrooms to the solution.[1] The version in The English Art of Cookery calls for dried mushrooms to be used for the ketchup's preparation.[6] This version also uses red wine in the ketchup's preparation, and uses a cooking reduction, in which one-third of the product is reduced, after which the final product is bottled.[6]

The book British Edible Fungi, published in 1891, states that for optimal results, "mixed fungi should not be used, beyond certain limits..."[1] Per this source, some species of mushrooms may be mixed together in mushroom ketchup's preparation, but certain species should not be mixed together, and some should not be mixed with others at all.[1] This book also includes a preparation for "double ketchup" that involves reducing mushroom ketchup to half its original state, which doubles its strength through the evaporation of water.[1]

In some instances in the late 19th century in the United States, ketchup sold in towns and labeled as "mushroom ketchup" did not actually contain mushrooms.[1] These products have been described as "easy to detect", and as distinguishable by the use of a microscope.[1]

Use in foods

In the 19th century, some sauces were prepared using mushroom ketchup, such as "quin sauce".[5] Quin sauce may be prepared by adding mushroom ketchup[5] or walnut ketchup, and anchovies to a prepared essence d'assortiment sauce,[7][8] the latter of which is prepared using white wine, vinegar, lemon juice, dried mushrooms, garlic, shallot, cloves, bay leaves mace, nutmeg, salt and pepper.[7]

Use in other condiments

An 1857 recipe for "camp ketchup" used mushroom ketchup as an ingredient, in addition to beer, white wine, anchovy, shallot, ginger, mace, nutmeg and black pepper.[3] The recipe combined these ingredients and then called for allowing the mixture to sit for fourteen days, after which it was bottled.[3] Additional 1857 recipes for camp ketchup used ingredients such as mushroom ketchup, vinegar, walnut ketchup, anchovy, soy, garlic, cayenne pods and salt.[3]

Varieties

Commercial varieties

Several commercial mushroom ketchups were produced in the United Kingdom; some of the brands included Crosse and Blackswell's Mushroom Catsup, Morton's Mushroom Ketchup and Geo Watkins Mushroom Ketchup.[9] Some of these companies exported their product to the United States, which created competition with ketchup products manufactured in the U.S. by the H. J. Heinz Company.[10]

Geo Watkins Mushroom Ketchup continues to be produced today. It is a commercial, mass-produced product that is marketed and purveyed to consumers,[2] and remains available in the United Kingdom.[11] The company was founded in 1830.[2][12] It is prepared in a liquid form and has a dark brown coloration.[12] Contemporary preparation of Geo Watkins Mushroom Ketchup consists mostly of water, salt, vinegar, chemically modified vegetable protein, and just 3% mushroom powder.[2]

See also

- Banana ketchup

- List of condiments

- List of sauces

- Mushroom sauce

-

Food portal

Food portal -

Fungi portal

Fungi portal -

History portal

History portal

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Cooke, Mordecai Cubitt (1891). British Edible Fungi. pp. 201–206.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Bell, Annie (June 5, 1999). "Condiments to the chef". The Independent. Retrieved 10 September 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Branston, Thomas F. (1857). The hand-book of practical receipts of every-day use. Lindsay & Blakiston. pp. 148–149.

- ↑ Bowles, Tom Parker (May 16, 2008). "Killer Ketchup: tracking down the best tomato ketchup". Daily Mail. Retrieved 11 September 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Smith 1996, pp. 16–17.

- 1 2 3 Briggs, Richard (1788). The English Art of Cookery, According to the Present Practice. G. G. J. and J. Robinson. pp. 595–596.

- 1 2 Jennings 1837, p. 163.

- ↑ Jennings 1837, p. 181.

- ↑ Smith 1996, 'p. 221.

- ↑ Money, N.P. (2011). Mushroom. Oxford University Press. p. 102. ISBN 978-0-19-991236-0.

- ↑ Tebben, M. (2014). Sauces: A Global History. Edible. Reaktion Books. p. pt25. ISBN 978-1-78023-413-7. Retrieved March 17, 2016.

- 1 2 Hawkins, Kathryn (2012). The Food of London: A Culinary Tour of Classic British Cuisine. Periplus world cookbooks. Tuttle Publishing. p. pt81. ISBN 978-1-4629-0975-9.

Bibliography

- Jennings, J. (1837). Two thousand five hundred practical Recipes in Family Cookery.

- Smith, Andrew F. (1996). Pure Ketchup. Univ of South Carolina Press. ISBN 1-57003-139-8.