Murder of Catrine da Costa

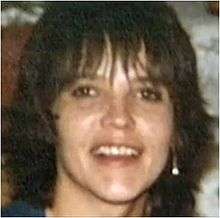

| Catrine da Costa | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

Catrine Beatrice Bäckström 19 June 1956 Luleå, Sweden |

| Disappeared | 10 July 1984 (aged 28) |

| Died |

c. July 1984 (aged 28) Solna, Sweden |

| Cause of death | Undetermined, considered homicide |

| Body discovered | 18 July and 8 August 1984 |

| Nationality | Swedish |

| Known for | Murder victim |

| Children | 1 |

Remains of Swedish prostitute Catrine da Costa (19 June 1956 – 1984) were found in Solna, north of Stockholm, in the late summer of 1984. Da Costa had been dismembered and parts of her body, in plastic bags, were found one kilometer apart on 18 July and 8 August. The case is known as Styckmordsrättegången (the dismemberment murder trial). How da Costa died has not been established, since vital organs and her head have not been found.

Background

Da Costa, who worked as a prostitute in Stockholm in the spring of 1984,[1][2][3] disappeared during Pentecost on 10 June, or soon thereafter.[4] On 18 July, the first parts of her dismembered body were discovered under a highway overpass in Solna, just outside Stockholm.[5] Da Costa's body was identified by her fingerprints.[4] Her head, internal organs, one breast and genitalia have never been found,[4][5] and no cause of death could be determined from what was found.[2]

Shortly thereafter, a pathologist in a forensics laboratory at Karolinska Institutet was suspected of the crime.[1] He was known to meet prostitutes, and his workplace was between the two places where the victim's body was found.[2] After his arrest, he was released.[1]

At this time, the wife of a general practitioner alerted the police that their 17-month-old daughter might be an incest victim.[6] Pediatric examinations found no evidence of abuse,[6] and the doctor and his wife separated in late 1984.[1] Later in 1985, the wife told police that her daughter had begun talking about witnessing a dismemberment.[6][7] Since the pathologist and the general practitioner knew each other superficially, the police connected the cases.[8] The following trials were largely based on the then-2½-year-old child's stories, interpreted by her mother and evaluated by a child psychologist and child psychiatrist.[2]

In 1986 police resources were stretched thin after the murder of Swedish Prime Minister Olof Palme, and the dismemberment case was shelved until the following year. The doctors were arrested in the fall of 1987 and brought to trial in January 1988.[9]

Trials

The first trial ended in a mistrial after a juror was interviewed for Aftonbladet on 9 March 1988 and commented on the court's justification for its judicial decision.[10] In a second trial, the lower court asked the Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare to investigate the circumstances of the case[1] and found that da Costa's cause of death was unknown. As a result, the two defendants were acquitted, since it could not be established that da Costa died under suspicious circumstances. Although in its verdict the court found that the defendants had dismembered the victim's body,[10] the statute of limitations for that crime had expired.[11]

On 23 May 1989 the Swedish authority for medical-negligence assessment rescinded the doctors' right to work, and its ruling was upheld in a 1991 appeal.[1] The doctors have appealed to several courts, including the Supreme Court of Sweden, the Supreme Administrative Court of Sweden (Regeringsrätten) and the European Court of Human Rights, none of which have overturned the ruling.[12]

Aftermath

The case has been the focus of several books, investigative articles and television documentaries. Journalist Per Lindeberg published Döden är en man (Death is a Man) in 1999, questioning the police investigation and contending that the men were victims of a miscarriage of justice caused partially by extensive media coverage. In 2003 journalist Lars Borgnäs published Sanningen är en sällsynt gäst (Truth is a Rare Guest), opposing Lindeberg's position and theorizing that da Costa was murdered by a serial killer.[13]

In 2006, the doctors demanded 40 million kroner in damages for loss of income during the years they could not practice and for defamation.[14][15] Their demand was refused when the Chancellor of Justice, who handles questions of voluntary damages, ruled that such a large claim should be handled by the courts.[16]

On 3 April 2007, the two men's attorney registered their claim for 35 million kroner in damages at the Attunda lower court.[17] On 30 November 2009 the trial of the Swedish state began, ending shortly before Christmas.[18][19] In an 18 February 2010 judgement, the court ruled that the doctors were not entitled to damages.[19][20] Da Costa's murder inspired Stieg Larsson to write The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo.[21]

Books about the case

- Olsson, Hanna – Catrine och rättvisan (1990)

- Lindeberg, Per – Döden är en man (1999; revised paperback edition 2008)

- Rajs, Jovan and Hjertén, Kristina – Ombud för de tystade (2001)

- Borgnäs, Lars – Sanningen är en sällsynt gäst (2003)

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Wahlberg, Stefan (27 May 2014). "30 år senare har de inte fått upprättelse" [30 years later, they have not had redress]. Metro (in Swedish). Retrieved 19 June 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 Bindel, Julie (30 November 2010). "The real-life Swedish murder that inspired Stieg Larsson". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 27 September 2014.

- ↑ Burstein, Dan; de Keijzer, Arne; Holmberg, John-Henri (2011). The Tattooed Girl: The Enigma of Stieg Larsson and the Secrets Behind the Most Compelling Thrillers of Our Time. St. Martin's Griffin. p. 152. ISBN 978-0312610562. Retrieved 27 September 2014.

- 1 2 3 "The Tattooed Girl". Retrieved 14 July 2015.

- 1 2 Bindel, Julie (30 November 2010). "The real-life Swedish murder that inspired Stieg Larsson". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 19 June 2015.

- 1 2 3 Foyen, Lars (9 March 1988). "Baby's testimony convicts doctors of murder". The Glasgow Herald. Stockholm. Reuters. p. 4. Retrieved 14 July 2015.

- ↑ "Daddys blogg - Daddys". Daddys. Retrieved 19 June 2015.

- ↑ Dugdale, John (1 November 2013). "Inside job: 10 crime writers turned detective". The Guardian. Retrieved 14 July 2015.

- ↑ Agell, Anders (24 November 2003). "Läkarna utsatta för rent justitiemord" [The doctors exposed to pure miscarriage of justice]. Dagens Nyheter (in Swedish). Retrieved 19 June 2015.

- 1 2 Rogeman, Anneli (10 January 2004). "Styckmordet har etsat sig fast i folksjälen" [The murder has been etched in the soul of the people]. Svenska Dagbladet (in Swedish). Archived from the original on June 18, 2015. Retrieved 19 June 2015.

- ↑ Lindström, Lars (4 December 2009). "Styckmordet blev en rättegång mot svenska rättvisan" [The murder became a trial against Swedish justice]. Expressen (in Swedish). Retrieved 19 June 2015.

- ↑ Nyberg, Patrik (30 January 2010). "Patrik Nybergs intervju med obducenten" [Patrik Nyberg interview with the pathologist] (in Swedish). Nyhetsverket.se. Retrieved 27 September 2014.

- ↑ "Mordet på Catrine" [The murder of Catrine]. Dagens Nyheter (in Swedish). 2005-08-16. Archived from the original on April 7, 2007.

- ↑ Melén, Johanna (3 April 2007). "Friades för styckmord - kräver miljonskadestånd" [Cleared of murder charges - calls for million crowns of damages]. Aftonbladet (in Swedish). Retrieved 19 June 2015.

- ↑ "Ett rättsfall som upprör - Styckmordet på Catrine da Costa" [A court case that upsets - The murder of Catrine da Costa] (in Swedish). Sveriges Television. 11 May 2005. Retrieved 19 June 2015.

- ↑ TT (18 February 2010). "Inget skadestånd för läkare" [No damages for doctors]. Svenska Dagbladet (in Swedish). Archived from the original on June 21, 2013. Retrieved 27 September 2014.

- ↑ "Läkare friade för styckmord kräver skadestånd" [Doctor acquitted of murder claims damages]. Dagens Nyheter (in Swedish). 2007-04-03. Archived from the original on April 7, 2007.

- ↑ TT (18 February 2010). "Inget skadestånd för läkare" [No damages for doctor]. Svenska Dagbladet (in Swedish). Retrieved 19 June 2015.

- 1 2 "The Local - Sweden's News in English". The Local. Archived from the original on October 6, 2014. Retrieved 27 September 2014.

- ↑ "No damages for docs in Da Costa murder case". The Local. 1984-06-10. Archived from the original on October 5, 2012. Retrieved 2012-08-08.

- ↑ Bindel, Julie (30 November 2010). "The real-life Swedish murder that inspired Stieg Larsson". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 15 July 2015.

External links

- Sjöberg, Lennart (2003-11-09). "A Case Of Alleged Cutting-Up Murder In Sweden: Legal Consequences Of Public Outrage". The Journal of Credibility Assessment and Witness Psychology. Department of Psychology of Boise State University. 4 (1): 37–62. ISSN 1088-0755. Retrieved 2007-04-04.

- Per Lindeberg's web site Mediemordet.com