Mule

| Mule | |

|---|---|

| |

| Domesticated | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Synapsida |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Perissodactyla |

| Family: | Equidae |

| Genus: | Equus |

| Species: | E. asinus × E. caballus |

| Synonyms | |

|

| |

.jpg)

A mule is the offspring of a male donkey (jack) and a female horse (mare).[1] Horses and donkeys are different species, with different numbers of chromosomes. Of the two F1 hybrids between these two species, a mule is easier to obtain than a hinny, which is the offspring of a female donkey (jenny) and a male horse (stallion).

The size of a mule and work to which it is put depend largely on the breeding of the mule's female parent (dam). Mules can be lightweight, medium weight, or when produced from draft horse mares, of moderately heavy weight.[2]:85–87 Mules are more patient, hardy and long-lived than horses, and are less obstinate and more intelligent than donkeys.[3]:5

Biology

The mule is valued because, while it has the size and ground-covering ability of its dam, it is stronger than a horse of similar size and inherits the endurance and disposition of the donkey sire, tending to require less food than a horse of similar size. Mules also tend to be more independent than most domesticated equines other than the donkey.

The median weight range for a mule is between about 370 and 460 kg (820 and 1,000 lb).[4] While a few mules can carry live weight up to 160 kg (353 lb), the superiority of the mule becomes apparent in their additional endurance.[5]

In general, a mule can be packed with dead weight of up to 20% of its body weight, or approximately 90 kg (198 lb).[5] Although it depends on the individual animal, it has been reported that mules trained by the Army of Pakistan can carry up to 72 kilograms (159 lb) and walk 26 kilometres (16.2 mi) without resting.[6] The average equine in general can carry up to approximately 30% of its body weight in live weight, such as a rider.[7]

A female mule that has estrus cycles and thus, in theory, could carry a fetus, is called a "molly" or "Molly mule," though the term is sometimes used to refer to female mules in general. Pregnancy is rare, but can occasionally occur naturally as well as through embryo transfer. A male mule is properly called a horse mule, though often called a john mule, which is the correct term for a gelded mule. A young male mule is called a mule colt, and a young female is called a mule filly.[8]

Characteristics

With its short thick head, long ears, thin limbs, small narrow hooves, and short mane, the mule shares characteristics of a donkey. In height and body, shape of neck and rump, uniformity of coat, and teeth, it appears horse-like. The mule comes in all sizes, shapes and conformations. There are mules that resemble huge draft horses, sturdy quarter horses, fine-boned racing horses, shaggy ponies and more.

The mule is an example of hybrid vigor.[9] Charles Darwin wrote: "The mule always appears to me a most surprising animal. That a hybrid should possess more reason, memory, obstinacy, social affection, powers of muscular endurance, and length of life, than either of its parents, seems to indicate that art has here outdone nature."[10]

The mule inherits from its sire the traits of intelligence, sure-footedness, toughness, endurance, disposition, and natural cautiousness. From its dam it inherits speed, conformation, and agility.[11]:5–6,8 Mules exhibit a higher cognitive intelligence than their parent species. This is also believed to be the result of hybrid vigor, similar to how mules acquire greater height and endurance than either parent.[12]

Handlers of working animals generally find mules preferable to horses: mules show more patience under the pressure of heavy weights, and their skin is harder and less sensitive than that of horses, rendering them more capable of resisting sun and rain. Their hooves are harder than horses', and they show a natural resistance to disease and insects. Many North American farmers with clay soil found mules superior as plow animals.

A mule does not sound exactly like a donkey or a horse. Instead, a mule makes a sound that is similar to a donkey's but also has the whinnying characteristics of a horse (often starts with a whinny, ends in a hee-haw). Mules sometimes whimper.

Color and size variety

Mules come in a variety of shapes, sizes and colors, from minis under 50 lb (23 kg) to maxis over 1,000 lb (454 kg), and in many different colors. The coats of mules come in the same varieties as those of horses. Common colors are sorrel, bay, black, and grey. Less common are white, roans (both blue and red), palomino, dun, and buckskin. Least common are paint mules or tobianos. Mules from Appaloosa mares produce wildly colored mules, much like their Appaloosa horse relatives, but with even wilder skewed colors. The Appaloosa color is produced by a complex of genes known as the Leopard complex (Lp). Mares homozygous for the Lp gene bred to any color donkey will produce an Appaloosa colored mule.

Distribution and use

Mules historically were used by armies to transport supplies, occasionally as mobile firing platforms for smaller cannons, and to pull heavier field guns with wheels over mountainous trails such as in Afghanistan during the Second Anglo-Afghan War.[13]

The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) reports that China was the top market for mules in 2003, closely followed by Mexico and many Central and South American nations.

Fertility

Mules and hinnies have 63 chromosomes, a mixture of the horse's 64 and the donkey's 62. The different structure and number usually prevents the chromosomes from pairing up properly and creating successful embryos, rendering most mules infertile.

There are no recorded cases of fertile mule stallions. A few mare mules have produced offspring when mated with a purebred horse or donkey.[14][15] Herodotus gives an account of such an event as an ill omen of Xerxes' invasion of Greece in 480 BC: "There happened also a portent of another kind while he was still at Sardis,—a mule brought forth young and gave birth to a mule" (Herodotus The Histories 7:57), and a mule's giving birth was a frequently recorded portent in antiquity, although scientific writers also doubted whether the thing was really possible (see e.g. Aristotle, Historia animalium, 6.24; Varro, De re rustica, 2.1.28).

As of October 2002, there had been only 60 documented cases of mules birthing foals since 1527.[15] In China in 2001, a mare mule produced a filly.[16] In Morocco in early 2002 and Colorado in 2007, mare mules produced colts.[15][17][18] Blood and hair samples from the Colorado birth verified that the mother was indeed a mule and the foal was indeed her offspring.[18]

A 1939 article in the Journal of Heredity describes two offspring of a fertile mare mule named "Old Bec", which was owned at the time by the A&M College of Texas (now Texas A&M University) in the late 1920s. One of the foals was a female, sired by a jack. Unlike its mother, it was sterile. The other, sired by a five-gaited Saddlebred stallion, exhibited no characteristics of any donkey. That horse, a stallion, was bred to several mares, which gave birth to live foals that showed no characteristics of the donkey.[19]

Modern mules

In the second half of the 20th century, widespread usage of mules declined in industrialized countries. The use of mules for farming and transportation of agricultural products largely gave way to modern tractors and trucks. However, in the United States, a dedicated number of mule breeders continued the tradition as a hobby and continued breeding the great lines of American Mammoth Jacks started in the United States by George Washington with the gift from the King of Spain of two Zamorano-Leonés donkeys. These hobby breeders began to utilize better mares for mule production until today's modern saddle mule emerged. Exhibition shows where mules pulled heavy loads have now been joined with mules competing in Western and English pleasure riding, as well as dressage and show jumping competition. There is now a cable TV show dedicated to the training of donkeys and mules. Mules, once snubbed at traditional horse shows, have been accepted for competition at the most exclusive horse shows in the world in all disciplines.

Mules are still used extensively to transport cargo in rugged roadless regions, such as the large wilderness areas of California's Sierra Nevada mountains or the Pasayten Wilderness of northern Washington state. Commercial pack mules are used recreationally, such as to supply mountaineering base camps, and also to supply trail building and maintenance crews, and backcountry footbridge building crews.[20] As of July 2014, there are at least sixteen commercial mule pack stations in business in the Sierra Nevada.[21] The Angeles chapter of the Sierra Club has a Mule Pack Section that organizes hiking trips with supplies carried by mules.[22]

Amish farmers, who reject tractors and most other modern technology for religious reasons, commonly use teams of six or eight mules to pull plows, disk harrows, and other farm equipment, though they use horses for pulling buggies on the road.

During the Soviet war in Afghanistan, the United States used large numbers of mules to carry weapons and supplies over Afghanistan's rugged terrain to the mujahideen.[23] Use of mules by U.S. forces has continued during the War in Afghanistan (2001-present), and the United States Marine Corps has conducted an 11-day Animal Packers Course since the 1960s at its Mountain Warfare Training Center located in the Sierra Nevada near Bridgeport, California.

Mule train

A 'mule train' is a connected or unconnected line of 'pack mules', usually carrying cargo. Because of the mule's ability to carry as much as a horse, their trait of being sure footed along with their tolerance of poorer coarser foods and abilities to tolerate arid terrains, Mule trains were common caravan organized means of animal powered bulk transport back into pre-classical times. In many climate and circumstantial instances, an equivalent string of pack horses would have to carry more fodder and sacks of high energy grains such as oats, so could carry less cargo. In modern times, strings of sure footed mules have been used to carry riders in dangerous but scenic back country terrain such as excursions into canyons.

Pack trains were instrumental in opening up the American West as the sure footed animals could carry up to 250 pounds, survive on rough forage,[lower-alpha 1] did not require feed, and could operate in the arid higher elevations of the Rockies, serving as the main cargo means to the west from Missouri during the heyday of the North American fur trade.[lower-alpha 2] Their use antedated the move west into the Rockies as colonial Americans sent out the first fur trappers and explorers past the Appalachians who were then followed west by high risk taking settlers by the 1750s (such as Daniel Boone) who led an increasing flood of emigrants that began pushing west over the into southern New York, and through the gaps of the Allegheny into the Ohio Country (the lands of western Province of Virginia and the Province of Pennsylvania), into Tennessee and Kentucky before and especially after the American Revolution.

Mule trains have been used as working (as opposed to tourist attractions) portions of transportation links as recently as 2005 by the World Food Programme.[24]

In the nineteenth century, Twenty-mule teams, for instance, were teams of eighteen mules and two horses attached to large wagons that ferried borax out of Death Valley from 1883 to 1889. The wagons were among the largest ever pulled by draft animals, designed to carry 10 short tons (9 metric tons) of borax ore at a time.[25]

Working mule train, Nicaragua 1957-1961

Working mule train, Nicaragua 1957-1961 1911 mule train in British Columbia

1911 mule train in British Columbia Grand Canyon on the South Kaibab trail

Grand Canyon on the South Kaibab trail 1868 mule train fording the Fraser River

1868 mule train fording the Fraser River

Mule clone

In 2003, researchers at University of Idaho and Utah State University produced the first mule clone as part of Project Idaho.[26] The research team included Gordon Woods, professor of animal and veterinary science at the University of Idaho; Kenneth L. White, Utah State University professor of animal science; and Dirk Vanderwall, University of Idaho assistant professor of animal and veterinary science. The baby mule, Idaho Gem, was born May 4. It was the first clone of a hybrid animal. Veterinary examinations of the foal and its surrogate mother showed them to be in good health soon after birth. The foal's DNA comes from a fetal cell culture first established in 1998 at the University of Idaho.

Gallery

.jpg) A pair of mules working a plowing exhibition at the Farnsley-Moreman House in Louisville, Kentucky (2005)

A pair of mules working a plowing exhibition at the Farnsley-Moreman House in Louisville, Kentucky (2005) Mule moving goods in the car-free Medina quarter in Fez, Morocco (2006)

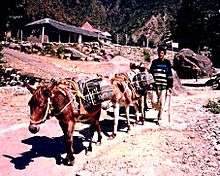

Mule moving goods in the car-free Medina quarter in Fez, Morocco (2006) Mules carrying slate roof tiles, Dharamsala, India (1993)

Mules carrying slate roof tiles, Dharamsala, India (1993) Mule heart

Mule heart

See also

|

Notes

- ↑ rough forage means Mules, Donkeys, and other asses, like many wild ungulates such as various deer species, can tolerate eating small shrubs, lichens and some branch ladened tree foliages and obtaining nutrition from such. In contrast, the digestive system of horses and to a lesser extent cattle are more dependent upon grasses, and evolved in climates where grasslands involved stands of grains and their high energy seed heads.

- ↑ The influence and effect of fur trading, especially for Beaver pelts between 1500-1940 is hard to understand these days when there are dozens of optional synthetic fabrics added to the repertoire of natural fiber materials. Many of the latter would only become widely available through the development of machinery processing (Cotton Gin, Spinning Jenny, etc.) making their use economical and widespread. The waterproofing wearing Beaver hats and coats was valuable in the days when transportation measured the six miles per hour of horsebacked travel as rapid transit.

References

- ↑ "Mule Day: A Local Legacy". americaslibrary.gov. Library of Congress. 2013-12-18. Retrieved 2014-07-16.

- ↑ Ensminger, M. E. (1990). Horses and Horsemanship: Animal Agriculture Series (Sixth ed.). Danville, IL: Interstate. ISBN 0-8134-2883-1.

- ↑ Jackson, Louise A (2004). The Mule Men: A History of Stock Packing in the Sierra Nevada. Missoula, MT: Mountain Press. ISBN 0-87842-499-7.

- ↑ "Mule". The Encyclopaedia Britannica: A Dictionary of Arts, Sciences, and General. XVII. Henry G. Allen and Company. 1888. p. 15. External link in

|title=(help) - 1 2 "Hunter's Specialties: More With Wayne Carlton On Elk Hunting". hunterspec.com. Hunter's Specialties. 2009. Archived from the original on 2010-10-08. Retrieved 2014-07-16.

- ↑ Khan, Aamer Ahmed (2005-10-19). "Beasts ease burden of quake victims". BBC. Retrieved 2010-04-06.

- ↑ American Endurance Ride Conference (November 2003). "Chapter 3, Section IV: Size". Endurance Rider's Handbook. AERC. Retrieved 2008-08-07.

- ↑ "Longear Lingo". lovelongears.com. American Donkey and Mule Society. 2013-05-22. Retrieved 2014-07-16.

- ↑ Chen, Z. Jeffrey; Birchler, James A., eds. (2013). Polyploid and Hybrid Genomics. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-470-96037-0. Retrieved 2014-07-16.

- ↑ Darwin, Charles (1879). What Mr. Darwin Saw in His Voyage Round the World in the Ship 'Beagle'. New York: Harper & Bros. pp. 33–34. Retrieved 2014-07-16.

- ↑ Hauer, John, ed. (2014). The Natural Superiority of Mules. Skyhorse. ISBN 978-1-62636-166-9. Retrieved 2014-07-16.

- ↑ Proops, Leanne; Faith Burden; Britta Osthaus (2008-07-18). "Mule cognition: a case of hybrid vigor?" (PDF). Animal Cognition. 12 (1): 75–84. doi:10.1007/s10071-008-0172-1. PMID 18636282. Retrieved 2008-08-10.

- ↑ Caption of Mule Battery WDL11495.png Library of Congress

- ↑ Savory, Theodore H (1970). "The Mule". Scientific American. 223 (6): 102–109. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican1270-102.

- 1 2 3 Kay, Katty (2002-10-02). "Morocco's miracle mule". BBC News. Retrieved 2009-02-05.

- ↑ Rong, Ruizhang; Cai, Huedi; Yang, Xiuqin; Wei, Jun (October 1985). "Fertile mule in China and her unusual foal" (PDF). Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. National Center for Biotechnology Information. 78 (10): 821–25. PMC 1289946

. PMID 4045884. Retrieved 13 July 2014.

. PMID 4045884. Retrieved 13 July 2014. - ↑ "Befuddling Birth: The Case of the Mule's Foal". National Public Radio. 2007-07-26. Retrieved 2009-02-05.

- 1 2 Lofholm, Nancy (2007-09-19). "Mule's foal fools genetics with 'impossible' birth". Denver Post.

- ↑ Anderson, W. S. (1939). "Fertile Mare Mules". Journal of Heredity. 30 (12): 549–551. Retrieved 2014-07-16.

- ↑ Jackson, Louise A (2004). The Mule Men: A History of Stock Packing in the Sierra Nevada. Missoula, MT: Mountain Press. ISBN 0-87842-499-7.

- ↑ "Members of the Eastern Sierra Packers". easternsierrapackers.com. Eastern Sierra Packers. 2009-01-18. Retrieved 2014-07-16.

- ↑ "Mule Pack Section, Angeles Chapter, Sierra Club". angeles.sierraclub.org. Angeles Chapter Sierra Club. 2014-04-18. Retrieved 2014-07-16.

- ↑ Bearden, Milt (2003) The Main Enemy, The Inside story of the CIA's Final showdown with the KGB. Presidio Press. ISBN 0345472500

- ↑ "Mule train provides lifeline for remote quake survivors". www.wfp.org. World Food Programme.

- ↑ "Mules hauling a 22,000lb boiler". Texas State Library and Archives Commission.

- ↑ "Project Idaho". University of Idaho. 2003-05-29. Archived from the original on 2009-08-09. Retrieved 2014-07-16.

Sources

-

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "article name needed". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "article name needed". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Further reading

- Arnold, Watson C. "The Mule: The Worker that 'Can't Get No Respect,'" Southwestern Historical Quarterly (2008) 112#1 pp: 34-50. online

- Buchholz, Katharina (2013-08-16). "Colorado miracle mule foal lived short life, but was well-loved". Denver Post. Retrieved 2014-07-16.

- Ellenberg, George B. Mule South to Tractor South: Mules, Machines, and the Transformation of the Cotton South (University of Alabama Press. 2007) 219pp * Chandley, A. C.; Clarke, C. A. (1985). "Cum mula peperit". Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 78 (10): 800–801. PMC 1289943

. PMID 4045882.

. PMID 4045882. - Loftus, Bill (August 2003). "It's a Mule: UI produces first equine clone". Here We Have Idaho: The University of Idaho Magazine. University of Idaho: 12–15. Retrieved 2014-07-16.

- Lukach, Mark (2013-09-11). "There Is a Man Wandering Around California With 3 Mules". The Atlantic. Atlantic Monthly Group. Retrieved 2014-07-16.

- Rong, R.; Chandley, A. C.; Song, J.; McBeath, S.; Tan, P. P.; Bai, Q.; Speed, R. M. (1988). "A fertile mule and hinny in China". Cytogenetic and Genome Research. 47 (3): 134–9. doi:10.1159/000132531. PMID 3378453.

- Williams, John O; Speelman, Sanford R (1948). "Mule production". Farmers' Bulletin. U.S. Department of Agriculture. 1341. Retrieved 2014-07-16. Hosted by the UNT Digital Library. Originally published by the U.S. Government Printing Office.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: |

| Look up mule in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Mule at Encyclopædia Britannica

- American Donkey and Mule Society

- American Mule Association

- British Mule Society

- Canadian Donkey & Mule Association

.jpg)