Mount Roraima

| Mount Roraima | |

|---|---|

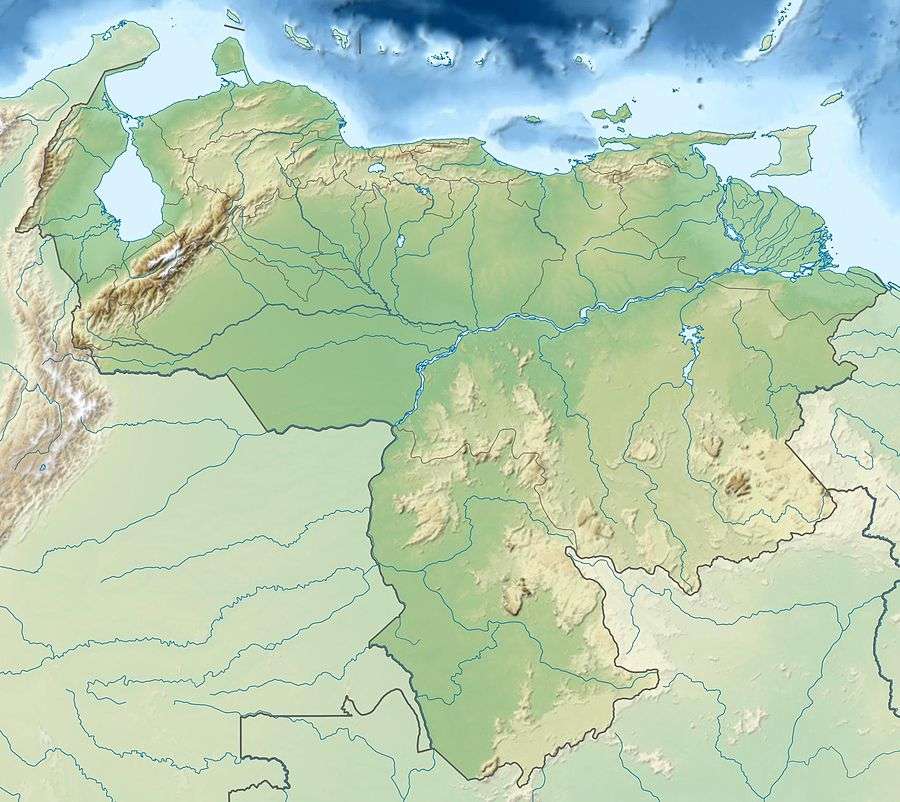

Mount Roraima Location of Mount Roraima in eastern Venezuela (on border with Guyana and Brazil) | |

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 2,810 m (9,220 ft) [1] |

| Prominence | 2,338 m (7,671 ft) [1] |

| Listing |

Country high point Ultra prominent peak |

| Coordinates | 5°08′36″N 60°45′45″W / 5.14333°N 60.76250°WCoordinates: 5°08′36″N 60°45′45″W / 5.14333°N 60.76250°W |

| Geography | |

| Location | Venezuela/Brazil/Guyana |

| Parent range | Guiana Highlands |

| Geology | |

| Mountain type | Plateau |

| Climbing | |

| First ascent | 1884, led by Sir Everard im Thurn and accompanied by Harry Inniss Perkins and several Guyanese natives[2][3]:497 |

| Easiest route | Hike |

Mount Roraima (Spanish: Monte Roraima [ˈmonte roˈɾaima], also known as Tepuy Roraima and Cerro Roraima; Portuguese: Monte Roraima [ˈmõtʃi ʁoˈɾajmɐ]) is the highest of the Pakaraima chain of tepui plateaus in South America.[4]:156 First described by the English explorer Sir Walter Raleigh during his expedition in 1595, its 31 km2 summit area[4]:156 is bounded on all sides by cliffs rising 400 metres (1,300 ft). The mountain also serves as the triple border point of Venezuela (85% of its territory), Guyana (10%) and Brazil (5%).[4]:156

Mount Roraima lies on the Guiana Shield in the southeastern corner of Venezuela's 30,000-square-kilometre (12,000 sq mi) Canaima National Park forming the highest peak of Guyana's Highland Range. The tabletop mountains of the park are considered some of the oldest geological formations on Earth, dating back to some two billion years ago in the Precambrian.

The highest point in Guyana and the highest point of the Brazilian state of Roraima lie on the plateau, but Venezuela and Brazil have higher mountains elsewhere. The triple border point is at 5°12′08″N 60°44′07″W / 5.20222°N 60.73528°W, but the mountain's highest point is Maverick Rock, 2,810 metres (9,219 ft), at the south end of the plateau and wholly within Venezuela.

Flora and fauna

Many of the species found on Roraima are unique to the tepui plateaus with 2 local endemic plants found on Roraima summit. Plants such as pitcher plants (Heliamphora), Campanula (a bellflower), and the rare Rapatea heather are commonly found on the escarpment and summit.[4]:156–157 It rains almost every day of the year. Almost the entire surface of the summit is bare sandstone, with only a few bushes (Bonnetia roraimœ) and algae present.[3]:517[5]:464[6]:63 Low scanty and bristling vegetation is also found in the small, sandy marshes that intersperse the rocky summit.[3]:517 Most of the nutrients that are present in the soil are washed away by torrents that cascade over the edge, forming some of the highest waterfalls in the world.

There are multiple examples of unique fauna atop Mount Roraima. Oreophrynella quelchii, commonly called the Roraima Bush Toad, is a diurnal toad usually found on open rock surfaces and shrubland. It is a species of toad in the family Bufonidae and breeds by direct development.[7] The species is currently listed as vulnerable and there is a need for increased education among tourists to make them aware of the importance of not handling these animals in the wild. Close population monitoring is also required, particularly since this species is known only from a single location. The species is protected in Monumento Natural Los Tepuyes in Venezuela, and Parque Nacional Monte Roraima in Brazil.[8]

Culture

Since long before the arrival of European explorers, the mountain has held a special significance for the indigenous people of the region, and it is central to many of their myths and legends. The Pemon and Kapon natives of the Gran Sabana see Mount Roraima as the stump of a mighty tree that once held all the fruits and tuberous vegetables in the world. Felled by Makunaima, their mythical trickster, the tree crashed to the ground, unleashing a terrible flood.[9] Roroi in the Pemon language means blue-green and ma means great.

Ascents

Although the steep sides of the plateau make it difficult to access, it was the first recorded major tepui to be climbed: Sir Everard im Thurn walked up a forested ramp in December 1884 to scale the plateau. This is the same route hikers take today.

The only non-technical route to the top is the Paraitepui route from Venezuela; any other approach will involve climbing gear. Mount Roraima has been climbed on a few occasions from the Guyana and Brazil sides, but as the mountain is entirely bordered on both these sides by enormous sheer cliffs that include high overhanging (negative-inclination) stretches, these are extremely difficult and technical rock climbing routes. Such climbs would also require difficult authorizations for entering restricted-access national parks in the respective countries.

In Brazil the Monte Roraima National Park lies within the Raposa Serra do Sol Indigenous Territory, and is not open to the public without permission.[10]

The 2013 Austrian documentary Jäger des Augenblicks - Ein Abenteuer am Mount Roraima (Moment Hunters - An Adventure on Mount Roraima) shows rock climbers Kurt Albert, Holger Heuber, and Stefan Glowacz climbing to the top of Mount Roraima from the Guyana side. Similarly, in 2010 Brazilian climbers Eliseu Frechou, Fernando Leal and Márcio Bruno opened a new route on the Guyanese side, climbing to the top in 12 days of a very difficult vertical wall climb.[11] They called the new route Guerra de Luz e Trevas (Portuguese for "War of Light and Darkness") and classed it as 6° VIIa A3 J4. A 28-minute Vimeo video called Dias de Tempestade (Days of Storm) is available documenting their climb (English subtitles, audio in Portuguese).

References

- 1 2 "Monte Roraima, Venezuela". Peakbagger.com.

- ↑ From The Times (May 22, 1885), "Mr. im Thurn's Achievement" (PDF), The New York Times, New York City, United States: The New York Times Company, p. 3, ISSN 0362-4331, OCLC 1645522, retrieved November 15, 2009,

Lord Aberdare said that Mr. Perkins, who accompanied Mr. im Thurn in the ascent of the mountain, had fared little better, inasmuch as he also had been severely attacked by fever since his return, and though present that evening, was still too weak to read his notes.

- 1 2 3 im Thurn, Everard (August 1885), "The Ascent of Mount Roraima", Proceedings of the Royal Geographical Society and Monthly Record of Geography, New Monthly Series, London, England, U.K.: Blackwell Publishing, on behalf of the Royal Geographical Society, with the Institute of British Geographers, 7 (8): 497–521, doi:10.2307/1800077, ISSN 0266-626X, JSTOR 1800077, OCLC 51205375, retrieved November 14, 2009,

For all around wore rocks and pinnacles of rocks of seemingly impossibly fantastic forms, standing in apparently impossibly fantastic ways—nay, placed one on or next to the other in positions seeming to defy every law of gravity—rocks in groups, rocks standing singly, rocks in terraces, rocks as columns, rocks as walls and rooks as pyramids, rocks ridiculous at every point with countless apparent caricatures of the faces and forms of men and animals, apparent caricatures of umbrellas, tortoises, churches, cannons, and of innumerable other most incongruous and unexpected objects.

- 1 2 3 4 Swan, Michael (1957), British Guiana, London, England, U.K.: Her Majesty's Stationery Office, OCLC 253238145,

Mount Roraima is the point where the boundaries of Venezuela, Brazil and British Guiana actually meet, and a stone stands on its summit, placed there by the International Commission in 1931.

- ↑ Clementi (née Eyres), Marie Penelope Rose (December 1916), "A Journey to the Summit of Mount Roraima", The Geographical Journal, London, England, U.K.: Blackwell Publishing, on behalf of the Royal Geographical Society, with the Institute of British Geographers, 48 (6): 456–473, doi:10.2307/1779816, ISSN 0016-7398, JSTOR 1779816, OCLC 1570660,

The summit is covered with enormous black boulders, weathered into the weirdest and most fantastic shapes. We were in the middle of an amphitheatre, encircled by what one might almost call waves of stone. It would be unsafe to explore this rugged plateau without white paint to mark one's way, for one would be very soon lost in the labyrinth of extraordinary rocks. There is no vegetation on Roraima save a few dampsodden bushes (Bonnetia Roraimœ), and fire sufficient for cooking can be raised only by an Indian squatting beside it and blowing all the time.

- ↑ Tate, G. H. H. (January 1930), "Notes on the Mount Roraima Region", Geographical Review, New York, New York, U.S.A.: American Geographical Society, 20 (1): 53–68, doi:10.2307/209126, ISSN 0016-7428, JSTOR 209126, OCLC 1570664,

In general the interior plateau looks flat and monotonous. Appearance is deceptive, for there are actually very few places where walking is not difficult, and these follow the joint system of the sandstone. For the most part, tumbled masses of rock, rifts, and gorges and whole acres of ten-foot mushrooms and loaves of bread formed in stone offer a maze in which one may wander long before finding better ground; while gullies many yards in depth and breadth, meandering undecidedly, force detours of sometimes half a mile.

- ↑ Hoogmoed, Marinus. "IUCN Red List of Threatened Species". Oreophrynella quelchii. IUCN 2012. Retrieved 13 December 2012.

- ↑ Geographical. "A Lost World Above the Clouds". Retrieved 13 December 2012.

- ↑ Abreu, Stela Azevedo de (July 1995), Aleluia: o banco de luz (8), Campinas, Brazil.: Thesis for a Master's in Sociocultural Anthropology, at UNICAMP, retrieved January 10, 2012

- ↑ Unidade de Conservação: Parque Nacional do Monte Roraima (in Portuguese), MMA: Ministério do Meio Ambiente, retrieved 2016-06-07

- ↑ Frechou, Eliseu (2010-01-24). "Eliseu Frechou e equipe chegam ao cume do Monte Roraima" [Eliseu Frechou and his team reach the top of Mount Roraima]. Extremos - Portal de Aventura (in Portuguese). Retrieved 2016-02-02.

Further reading

- Aubrecht, R., T. Lánczos, M. Gregor, J. Schlögl, B. Šmída, P. Liščák, C. Brewer-Carías & L. Vlček (15 September 2011). Sandstone caves on Venezuelan tepuis: return to pseudokarst? Geomorphology 132(3–4): 351–365. doi:10.1016/j.geomorph.2011.05.023

- Aubrecht, R., T. Lánczos, M. Gregor, J. Schlögl, B. Šmída, P. Liščák, C. Brewer-Carías & L. Vlček (2013). Reply to the comment on "Sandstone caves on Venezuelan tepuis: return to pseudokarst?". Geomorphology, published online on 30 November 2012. doi:10.1016/j.geomorph.2012.11.017

- (Spanish) Brewer-Carías, C. (2012). "Roraima: madre de todos los ríos." (PDF). Río Verde 8: 77–94.

- Jaffe, K., J. Lattke & R. Perez-Hernández (January–June 1993). Ants on the tepuies of the Guiana Shield: a zoogeographic study. Ecotropicos 6(1): 21–28.

- Kok, P.J.R., R.D. MacCulloch, D.B. Means, K. Roelants, I. Van Bocxlaer & F. Bossuyt (7 August 2012). "Low genetic diversity in tepui summit vertebrates." (PDF). Current Biology 22(15): R589–R590. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2012.06.034 ["supplementary information" (PDF).]

- MacCulloch, R.D., A. Lathrop, R.P. Reynolds, J.C. Senaris and G.E. Schneider. (2007). Herpetofauna of Mount Roraima, Guiana Shield region, northeastern South America. Herpetological Review 38: 24-30.

- Sauro, F., L. Piccini, M. Mecchia & J. De Waele (2013). Comment on "Sandstone caves on Venezuelan tepuis: return to pseudokarst?" by R. Aubrecht, T. Lánczos, M. Gregor, J. Schlögl, B. Smída, P. Liscák, Ch. Brewer-Carías, L. Vlcek, Geomorphology 132 (2011), 351–365. Geomorphology, published online on 29 November 2012. doi:10.1016/j.geomorph.2012.11.015

- Warren, A. (1973). Roraima: report of the 1970 British expedition to Mount Roraima in Guyana, South America. Seacourt Press, Oxford UK, 152 pp.

- Zahl, Paul, A. (1940) To the Lost World. George G. Harrap & Co. Ltd. 182 High Holborn, London, W.C.1

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mount Roraima. |

- Mount Roraima Information

- Mount Roraima on SummitPost.org

- National Geographic's 2004 Biological Exploration of the Cliffs

- A walk around the top of Mount Roraima

- Dias de Tempestade (Days of Storm) - 28-minute short documentary on Vimeo (in Portuguese, with English subtitles) showing the 2010 climb of Mount Roraima from the Guyana side by Brazilian climber Eliseu Frechou and his team.