Moundville Archaeological Site

|

Moundville Archaeological Site | |

|

A view of the site from the top of Mound B looking toward Mound A and the plaza. | |

| |

| Location |

634 Mound State Parkway Moundville, Alabama, USA |

|---|---|

| Nearest city | Tuscaloosa |

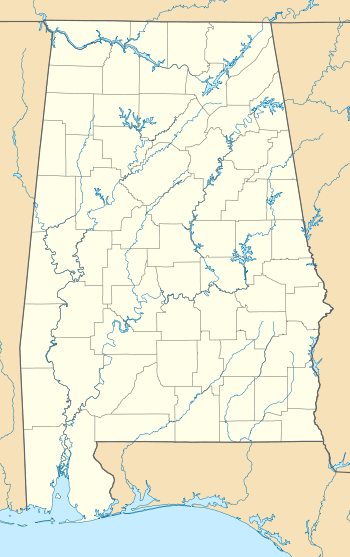

| Coordinates | 33°0′16.81″N 87°37′51.85″W / 33.0046694°N 87.6310694°WCoordinates: 33°0′16.81″N 87°37′51.85″W / 33.0046694°N 87.6310694°W |

| NRHP Reference # | 66000149 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | October 15, 1966[1] |

| Designated NHL | July 19, 1964 [2] |

Moundville Archaeological Site, also known as the Moundville Archaeological Park, is a Mississippian culture site on the Black Warrior River in Hale County, near the city of Tuscaloosa, Alabama.[3] Extensive archaeological investigation has shown that the site was the political and ceremonial center of a regionally organized Mississippian culture chiefdom polity between the 11th and 16th centuries. The archaeological park portion of the site is administered by the University of Alabama Museums and encompasses 185 acres (75 ha), consisting of 29 platform mounds around a rectangular plaza.[3]

The site was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1964 and was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1966.[2]

Moundville is the second-largest site in the United States of the classic Middle Mississippian era, after Cahokia in Illinois. The culture was expressed in villages and chiefdoms throughout the central Mississippi River Valley, the lower Ohio River Valley, and most of the Mid-South area, including Kentucky, Tennessee, Alabama, and Mississippi as the core of the classic Mississippian culture area.[4] The park contains a museum and an archaeological laboratory.

Bottle Creek Indian Mounds, located on an island north of Mobile, is another major Mississippian site in Alabama on the Gulf Coast. It has also been designated as an NHL.

History

Moundville was mentioned by E. G. Squier and Edwin Hamilton Davis in their work, "Ancient Monuments of the Mississippi Valley" (c1848). Later in the century, Nathaniel Thomas Lupton created a fairly accurate map of the site.

Very little work was conducted at Moundville by the Bureau of Ethnology’s Division of Mound Exploration, partly because the landowner imposed a fee. The first significant archaeological investigations were conducted by Clarence Bloomfield Moore, a lawyer from Philadelphia. He dug extensively at Moundville in 1906 and his extensive records of his excavation have been of use to modern archaeologists. Unfortunately, the site was looted extensively over the next two decades.

In the mid-1920’s concerned citizens, including Walter B. Jones (geologist) (after whom the site’s museum is named) had begun a concerted effort to save the site. With the help of the Alabama Museum of Natural History, the land containing the mounds was slowly purchased. By 1933 the site had officially become known as Mound State Park, but the park was not developed until 1938. The Civilian Conservation Corps was brought in to stabilize the mounds against erosion. They also constructed roads and buildings for the site. The name of the park was changed to Mound State Monument and was open to the public in 1939.

In 1991, the park’s name was officially changed to Moundville Archaeological Park.

Site

The site was occupied by Native Americans of the Mississippian culture from around 1000 AD to 1450 AD.[3] Around 1150 AD it began its rise from a local to a regional center. At its height, the community took the form of a roughly 300-acre (121 ha) residential and political area protected on three sides by a bastioned wooden palisade wall, with the remaining side protected by the river bluff.[3]

The largest platform mounds are located on the northern edge of the plaza and become increasingly smaller going either clockwise or counter clockwise around the plaza to the south. Scholars theorize that the highest-ranking clans occupied the large northern mounds, with the smaller mounds' supporting buildings used for residences, mortuary, and other purposes. A total of 29 remain on the site.[3] Of the two largest mounds in the group, Mound A occupies a central position in the great plaza, and Mound B lies just to the north, a steep, 58 feet (18 m) tall pyramidal mound with two access ramps.[3] Along with both mounds, archaeologists have also found evidence of borrow pits, other public buildings, and a dozen small houses constructed of pole and thatch.

Archaeologists have interpreted this community plan as a sociogram, an architectural depiction of a social order based on ranked clans. According to this model, the Moundville community was segmented into a variety of different clan precincts, the ranked position of which was represented in the size and arrangement of paired earthen mounds around the central plaza. By 1300, the site was being used more as a religious and political center than as a residential town.[3] This signaled the beginning of a decline, and by 1500 most of the area was abandoned.[3]

People

The surrounding area appears to have been heavily populated, but the people built relatively few mounds before 1200 AD, after which the public architecture of the plaza and mounds was constructed.[3] At its height, the population is estimated to have been around 1000 people within the walls, with 10,000 additional people in the surrounding countryside.[3] Based on findings during excavations, the residents of the site were skilled in agriculture, especially the cultivation of maize. Production of maize surpluses gave the people produce to trade for other goods, supported population density, and allowed the specialization of artisans.[3] Extensive amounts of imported luxury goods, such as copper, mica, galena, and marine shell, have been excavated from the site.[3] The site is renowned by scholars for the artistic excellence of the artifacts of pottery, stonework, and embossed copper left by the former residents.[3]

Excavations and interpretation

The first major excavations were done in 1905-06 by Clarence Bloomfield Moore, an independent archeologist, before archaeology had become a professional field of scholarship. His work first brought the site national attention and contributed to archaeologists developing the concept of the Southeastern Ceremonial Complex.[5] One of his many discoveries was a finely carved diorite bowl depicting a crested wood duck, which he later donated to the Smithsonian Institution, together with more than 500 other pieces.[5]

Although the state had shown little interest in the site, after Moore removed this and many other of the site's finest artifacts, the Alabama Legislature prohibited people from taking any other artifacts from the state. Archaeological techniques in general were relatively crude when compared to modern standards, but some professionals even during his time criticized Moore for his excavation techniques.[5]

The first large-scale scientific excavations of the site began in 1929 by Walter B. Jones, director of the Alabama Museum of Natural History, and the archaeologist David L. DeJarnette.[6] During the 1930s, he used some workers from the Civilian Conservation Corps, a program of the President Franklin D. Roosevelt administration during the Great Depression.

In the early 21st century, work is led by Dr. Jim Knight, Curator of Southeastern Archaeology at the University of Alabama. He is conducting field research at Moundville with an emphasis on ethnohistorical reconstruction. A ceremonial "earth lodge." was discovered in 2007, and about 15 percent of the site has been excavated.[7] The Jones Archaeological Museum was constructed on the park property, and opened in 2010 for display of artifacts collected at the site and interpretation of the ancient people and culture. The University of Alabama maintains an archaeological lab at the park as well.

Ceramics

Two major varieties of pottery are associated with the Moundville Site. The Hemphill style pottery is a locally produced ware with a distinctive engraving tradition. The other variety consists of painted vessels, many of which were not produced locally. Unlike the engraved pottery, the negative-painted pottery seems to have been used only by the elites at the Moundville site; it has not been found outside the site.[8]

Geography

The Moundville Archaeological Site is located on a bluff overlooking the Black Warrior River. The site and other affiliated settlements are located within a portion of the Black Warrior River Valley starting below the fall line, just south of Tuscaloosa, Alabama, and extending 25 miles (40 km) downriver. Below the fall line, the valley widens and the uplands consist of rolling hills dissected by intermittent streams. This region corresponds with the transition between the Piedmont and Coastal Plain and encompasses considerable physiographic and ecological diversity. Environmentally this portion of the Black Warrior Valley was an ecotone that had floral and faunal characteristics from temperate oak-hickory, maritime magnolia, and pine forests.

Easter sunrise pageant

From 1947 until 1999, there was an Easter sunrise pageant at the park. The program, entitled ‘The Road to Calvary’ was written by Methodist minister, Robert L. Haygood, and was enacted by local residents. The show consisted of tableaus on the mounds reenacting the last days of Jesus’ life concluding with Christ on the cross silhouetted by the rising sun. The tableaus were accompanied by narration, music, and singing from local church choirs. At its peak, attendance was numbered in the thousands. For the pageant, the park opened at 3:00am with the program starting at 5:00am. Admission was free.

Representation in media

The American independent film, A Genesis Found (2009), was largely shot and set at the Moundville Archaeological Site. The plot concerns a search for a supposed anomalous skeleton linked to the site's founding. It features a dramatized dig from a University of Alabama Field School. The film also features dramatizations of Civilian Conservation Corps digs in the 1930s, as well as details about some of the site's more popular motifs and imagery.

See also

- List of Mississippian sites

- Mississippi Valley: Culture, phase, and chronological periods table - List of archaeological periods

- List of National Historic Landmarks in Alabama

Further reading

- Knight, Vernon James, Jr. Mound Excavations at Moundville: Architecture, Elites, and Social Order (University of Alabama Press; 2010) 404

- Knight, Vernon James, Jr. 2004 "Characterizing Elite Midden Mounds at Moundville", American Antiquity 69(1):304-321.

- Knight, Vernon James, Jr. 1998 "Moundville as a Diagrammatic Ceremonial Center", Archaeology of the Moundville Chiefdom, edited by V.J. Knight Jr. and V.P. Steponaitis, pp. 44–62. Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press.

- Steponaitis, Vincas P. 1983 Ceramics, Chronology, and Community Patterns: An Archaeological Study at Moundville. Academic Press, New York.

- Welch, Paul D. 1991 Moundville's Economy. University of Alabama Press, Tuscaloosa.

- Welch, Paul D., and C. Margaret Scarry. 1995 "Status-related Variation in Foodways in the Moundville Chiefdom", American Antiquity 60:397-419.

- Wilson, Gregory D. 2008 The Archaeology of Everyday Life at Early Moundville, University of Alabama Press, Tuscaloosa.

References

- ↑ National Park Service (2007-01-23). "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service.

- 1 2 "Moundville Site". National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service. Retrieved 2007-10-28.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 "An Archaeological Sketch of Moundville". "Moundville Archaeological Museum". Archived from the original on 2007-11-18. Retrieved 2007-12-04.

- ↑ "Southeastern Prehistory: Mississippian and Late Prehistoric Period". "National Park Service". Retrieved 2007-12-04.

- 1 2 3 "Moundville: A Breathtaking Archaeological Find in Alabama". "Laura Lee News". 2007. Retrieved 2007-12-13.

- ↑ "HistoricalStatement". "University of Alabama: Office of Archaeological Research". Archived from the original on 2007-08-15. Retrieved 2007-12-04.

- ↑ "Vernon J. Knight". Department of Anthropology, University of Alabama. Archived from the original on February 8, 2007. Retrieved 2007-12-13.

- ↑ Steponaitis, Vincas P.; Knight, Vernon J. Jr. (2003-08-08). "Moundville Art in Historical and Social Context" (PDF). Retrieved 2010-08-22.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Moundville Archaeological Site. |