Mohorovičić discontinuity

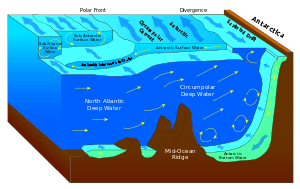

The Mohorovičić discontinuity (Croatian pronunciation: [moxorôʋiːt͡ʃit͡ɕ]),[1] usually referred to as the Moho, is the boundary between the Earth's crust and the mantle. Named after the pioneering Croatian seismologist Andrija Mohorovičić, the Moho separates both the oceanic crust and continental crust from underlying mantle. The Moho lies almost entirely within the lithosphere; only beneath mid-ocean ridges does it define the lithosphere–asthenosphere boundary. The Mohorovičić discontinuity was first identified in 1909 by Mohorovičić, when he observed that seismograms from shallow-focus earthquakes had two sets of P-waves and S-waves, one that followed a direct path near the Earth's surface and the other refracted by a high-velocity medium.[2]

The Mohorovičić discontinuity is 5 to 10 kilometres (3–6 mi) below the ocean floor, and 20 to 90 kilometres (10–60 mi), with an average of 35 kilometres (22 mi), beneath typical continental crusts.[3]

Nature

Immediately above the Moho, the velocities of primary seismic waves (P-waves) are consistent with those through basalt (6.7–7.2 km/s), and below they are similar to those through peridotite or dunite (7.6–8.6 km/s).[4] That suggests the Moho marks a change of composition, but the interface appears to be too even for any believable sorting mechanism within the Earth. Near-surface observations suggest such sorting produces an irregular surface.[5]

The Moho is characterized by a transition zone of up to 500 m thick.[6] Ancient Moho zones are exposed above-ground in numerous ophiolites around the world.

Exploration

During the late 1950s and early 1960s the executive committee of the U.S. National Science Foundation funded drilling a hole through the ocean floor to reach this boundary. However the operation, named Project Mohole, never received sufficient support and was mismanaged; the United States Congress canceled it in 1967. Soviet scientists at the Kola Institute pursued the goal simultaneously; after 15 years they reached a depth of 12,260 metres (40,220 ft), the world's deepest hole, before abandoning their attempt in 1989.[7]

Reaching the discontinuity remains an important scientific objective. One proposal considers a rock-melting radionuclide-powered capsule with a heavy tungsten needle that can propel itself down to the Moho discontinuity and explore Earth's interior near it and in the upper mantle.[8] The Japanese project Chikyu Hakken ("Earth Discovery") also aims to explore in this general area with the drilling ship, Chikyū, built for the Integrated Ocean Drilling Program (IODP).

Plans called for the drill-ship JOIDES Resolution to sail from Colombo in Sri Lanka in late 2015 and to head for the Atlantis Bank, a promising location in the southwestern Indian Ocean on the Southwest Indian Ridge, to attempt to drill an initial bore hole to a depth of approximately 1.5 kilometres.[9] The attempt did not reach 1300m, but researchers hope to further their investigations at a later date.[10]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Mangold, Max (2005). Aussprachewörterbuch (in German) (6th ed.). Mannheim: Dudenverlag. p. 559. ISBN 9783411040667.

- 1 2 Andrew McLeish (1992). Geological science (2nd ed.). Thomas Nelson & Sons. p. 122. ISBN 0-17-448221-3.

- ↑ James Stewart Monroe; Reed Wicander (2008). The changing Earth: exploring geology and evolution (5th ed.). Cengage Learning. p. 216. ISBN 0-495-55480-4.

- ↑ RB Cathcart & MM Ćirković (2006). Viorel Badescu; Richard Brook Cathcart & Roelof D. Schuiling, eds. Macro-engineering: a challenge for the future. Springer. p. 169. ISBN 1-4020-3739-2.

- ↑ Benjamin Franklin Howell (1990). An introduction to seismological research: history and development. Cambridge University Press. p. 77 ff. ISBN 0-521-38571-7.

- ↑ D.P. McKenzie - The Mohorovičić Discontinuity

- ↑ "How the Soviets Drilled the Deepest Hole in the World". Wired. 2008-08-25. Retrieved 2008-08-26.

- ↑ Ozhovan, M.; F. Gibb; P. Poluektov & E. Emets (August 2005). "Probing of the Interior Layers of the Earth with Self-Sinking Capsules". Atomic Energy. 99 (2): 556–562. doi:10.1007/s10512-005-0246-y.

- ↑ Witze, Alexandra (December 2015). "Quest to drill into Earth's mantle restarts". Nature News.

- ↑ Kavanagh, Lucas (2016-01-27). "Looking Back on Expedition 360". JOIDES Resolution. Retrieved 2016-09-21.

We may not have made it to our goal of 1300 m, but we did drill the deepest ever single-leg hole into hard rock (789 m), which is currently the 5th deepest ever drilled into the hard ocean crust. We also obtained both the longest (2.85 m) and widest (18 cm) single pieces of hard rock ever recovered by the International Ocean Discovery Program and its predecessors! [...] Our hopes are high to return to this site in the not too distant future.

References

- Harris, P. (1972). "The composition of the earth". In Gass, I. G.; et al. Understanding the earth: a reader in the earth sciences. Horsham: Artemis Press for the Open University Press. ISBN 0-85141-308-0.

- "Schlumberger Oilfield Glossary". Schlumberger. Retrieved 2008-07-17.

- Dixon, Dougal (2000). Beginner's Guide to Geology. New York: Bounty Books. ISBN 0-7537-0358-0.

External links

- Britt, Robert Roy (2005-04-07). "Hole Drilled to Bottom of Earth's Crust, Breakthrough to Mantle Looms". Imaginova. Retrieved 2008-07-17.

- "Digging a Hole in the Ocean: Project Mohole, 1958-1966". National Academy of Sciences. Retrieved 2008-07-17.

- Map of the Moho depth of the European plate