Mission San Carlos Borromeo de Carmelo

|

The façade of the capilla (chapel) at Mission San Carlos Borromeo de Carmelo. | |

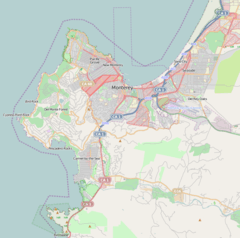

Location in the Monterey Peninsula | |

| Location | 3080 Rio Rd.Carmel-by-the-Sea, California, 93923 |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 36°32′34″N 121°55′7″W / 36.54278°N 121.91861°WCoordinates: 36°32′34″N 121°55′7″W / 36.54278°N 121.91861°W |

| Name as founded | La Misión San Carlos Borromeo del Río Carmelo [1] |

| English translation | The Mission of Saint Charles Borromeo of the Carmel River |

| Patron | Saint Charles Borromeo [2] |

| Nickname(s) | "Father of the Alta California Missions" [3] |

| Founding date | June 3, 1770 [4] |

| Founding priest(s) | Father Presidente Junípero Serra[5] |

| Founding Order | Second [2] |

| Headquarters of the Alta California Mission System |

1771–1815; 1819–1824; 1827–1830 [6] |

| Military district | Third [7] |

| Native tribe(s) Spanish name(s) |

Esselen, Ohlone Costeño |

| Native place name(s) | Ekheya [8] |

| Baptisms | 3,827 [9] |

| Marriages | 1,032 [9] |

| Burials | 2,837 [9] |

| Secularized | 1834 [2] |

| Returned to the Church | 1859 [2] |

| Governing body | Roman Catholic Diocese of Monterey |

| Current use | Parish Church/Minor Basilica |

| Official name: Carmel Mission | |

| Designated | October 15, 1966[10] |

| Reference no. | 66000214[10] |

| Designated | October 9, 1960[11] |

| Reference no. |

|

| Website | |

| http://carmelmission.org | |

Mission San Carlos Borromeo del río Carmelo, also known as the Carmel Mission or Mission Carmel, is a Roman Catholic mission church in Carmel-by-the-Sea, California. It is on the National Register of Historic Places and a U.S. National Historic Landmark. The mission was the headquarters of the Alta California missions headed by Saint Junípero Serra from 1770 until his death in 1784. It was also the seat of the second presidente, Father Fermin Francisco de Lasuen.[notes 1]

The mission buildings and lands were secularized by the Mexican government in 1833, and had fallen into disrepair by the mid-19th century. They were partially restored beginning in 1884.[13][14] In 1886 it was transferred from the Franciscans to the local diocese and has continued as a parish church since then. It is the only one of the California Missions to have its original bell tower dome.

History

)_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg)

Mission Carmel is the second mission built by Franciscan missionaries in Upper California. It was first established as Mission San Carlos Borromeo in Monterey, California near the native village of Tamo on June 3, 1770. It was named for Carlo Borromeo, Archbishop of Milan, Italy. It was the site of the first Christian confirmation in Alta California.[5] When the mission moved, the original building continued to operate as the Royal Presidio chapel and later became the current Cathedral of San Carlos Borromeo.

Relocation to Carmel

Pedro Fages, who served as military governor of Alta California between 1770 and 1774, kept his headquarters at the Presidio of Monterey, the capital of Alta California. He worked his men very harshly and was seen as a tyrant. Serra intervened on behalf of Fages' soldiers, and the two men did not get along.[15][16] The soldiers raped the Indian woman and kept them as concubines.[15] Serra wanted to put some distance between the missions neophytes and Fages' soldiers.

Serra found that the land was near the mouth of the Carmel River was better suited for farming.[17] In May 1771, Spain's viceroy approved Serra's petition to relocate the mission to its current location near the Carmel River.[notes 2] The relocated mission was renamed Mission San Carlos Borromeo del Río Carmelo.

Indian baptism and conscription

After the Carmel mission was moved to Carmel Valley, the Franciscans began to baptize some natives.[18] By the end of 1771, the population of mission was 15 with an additional 22 baptized Indians, out of a total population of northern California of 60.[17] Farming was not very productive and for several years the mission was dependent upon the arrival of supply ships.[17] Historian Jame Culleton wrote in 1950, "The summer of '73 came without bringing the supply ship. Neither Carmel nor Monterey was anything like self-supporting."[17] To improve baptismal rates, they sought to convert key members of the Esselen and Rumsen tribes, including chiefs. This persuaded some Indians to follow them to the mission.

The Esselen and Ohlone Indians who lived near the mission were baptized and then forcibly relocated and conscripted into forced labor as plowmen, shepherds, cattle herders, blacksmiths, and carpenters on the mission. Disease, starvation, overwork, and torture decimated these tribes.[19]:114 Native neophyte laborers made the adobe bricks, roof tiles and tools needed to build the mission. In the beginning, the mission relied on bear meat from Mission San Antonio de Padua and supplies brought by ship from Mission San Diego de Alcalá. In 1794, the population reached its peak of 927, but by 1823 the total had dwindled to 381. There was extensive "comingling of the Costanoan with peoples of different linguistic and cultural background during the mission period."[18]

On November 20, 1818, French privateer Hipólito Bouchard raided the nearby Monterey Presidio before moving on to other Spanish installations in the south.

Secularized and abandoned

The mission was secularized by the newly independent Mexican government in August 1833 with the stipulation that half the mission lands would be awarded to the native people. This purpose was largely subverted however. The priests could not maintain the missions without the Indians' forced labor and they were soon abandoned. The Indians drifted from the mission. Some found work on farms and ranches in exchange for room and board.

Restoration

The Carmel Mission was in ruins when the Roman Catholic Church regained control of the mission building and the land in 1863. In 1884 Father Angel Casanova began to restore the mission building. In 1931 Monsignor Philip Scher appointed Harry Downie as the curator in charge of mission restoration. Two years later, the church transferred the mission from the Franciscans to the local diocese and it became a regular parish church. In 1960, the mission was designated as a minor basilica by Pope John XXIII. Downie labored for virtually the rest of his life to restore the mission, ancillary buildings and walls, and the grounds. In 1987, Pope John Paul II visited the mission as part of his U.S. tour.[20]

"Mission Carmel", as it came to be known, was Serra's favorite and, because it was close to Monterey, the capital of Alta California, he chose it as his headquarters. When he died on August 28, 1784, he was interred beneath the chapel floor.

Today

_-_basilica_interior%2C_nave.jpg)

As a result of Downie's dedicated efforts to restore the buildings, the Carmel mission church is one of the most authentically restored of all the mission churches in California. Mission Carmel has been designated a National Historic Landmark by the National Park Service. It is an active parish church of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Monterey.[21]

In addition to its activity as a place of worship, Mission Carmel also hosts concerts, art exhibits, lectures and numerous other community events. In 1986, then-pastor Monsignor Eamon MacMahon acquired a magnificent Casavant Frères organ complete with horizontal trumpets. Its hand-painted casework is decorated with elaborate carvings and statuary reflecting the Spanish decorative style seen on the main altar.

The mission also serves as a museum, preserving its own history and the history of the area. There are four specific museum galleries: the Harry Downie Museum, describing restoration efforts; the Munras Family Heritage Museum, describing the history of one of the most important area families; the Jo Mora Chapel Gallery, hosting rotating art exhibits as well as the monumental bronze and travertine cenotaph (1924) sculpted by Jo Mora;[22] and the Convento Museum, which holds the cell Serra lived and died in, as well as interpretive exhibits. At one end of the museum is a special chapel room containing some of the vestments used by Serra.[23][24][25]

The mission grounds are also the location of the Junipero Serra School, a private Catholic school for kindergartners through 8th grade.[26]

Notable interments

_-_basilica%2C_interior%2C_grave_of_Junipero_Serra.jpg)

Several notable people are buried in the church and churchyard.

- Juan Crespí (1721–1782), Spanish missionary and explorer

- Fermín Lasuén (1736–1803), Spanish missionary

- José Antonio Roméu, (1742? – 1792) Spanish governor of California

- Junípero Serra (1713–1784), founder of the mission

See also

- Cathedral of San Carlos Borroméo (aka Royal Presidio Chapel), Monterey, California

- USNS Mission Carmel (AO-113), a Buenaventura Class fleet oiler built during World War II.

- USNS Mission San Carlos (AO-120), a Buenaventura Class fleet oiler built during World War II.

Notes

- ↑ The priests forcibly conscripted the native Costonoan Indian populations and commingled many disparate tribes including the Esselen, requiring them to work as laborers, herders, farmers, and other trades, and baptized them. Many died as a result of exposure to European disease and starvation.

- ↑ Smith, p. 18: The mission was established in the new location on August 1, 1771; the first mass was celebrated on August 24, and Serra officially took up residence in the newly constructed buildings on December 24.

References

- ↑ Leffingwell, p. 113

- 1 2 3 4 Krell, p. 83

- ↑ Ruscin, p. 25

- ↑ Yenne, p. 33

- 1 2 Ruscin, p. 196

- ↑ Yenne, p. 186

- ↑ Forbes, p. 202

- ↑ Ruscin, p. 195

- 1 2 3 Krell, p. 315: as of December 31, 1832; information adapted from Engelhardt's Missions and Missionaries of California.

- 1 2 National Park Service (2010-07-09). "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service.

- ↑ NHL Summary

- ↑ "Mission San Carlos Borromeo de Carmelo". Office of Historic Preservation, California State Parks. Retrieved 2012-11-23.

- ↑ Dillon, James (September 4, 1976). "Mission San Carlos De Borromeo Del Rio Carmelo" (pdf). National Register of Historic Places – Inventory Nomination Form. National Park Service. Retrieved 22 May 2012.

- ↑ "Mission San Carlos De Borromeo Del Rio Carmelo" (pdf). Photographs. National Park Service. Retrieved 22 May 2012.

- 1 2 Walton, John (2003). Storied Land: Community and Memory in Monterey. Berkeley, Calif.: University of California Press. p. 15ff. ISBN 9780520935679. Retrieved 5 September 2016.

- ↑ Paddison, p. 23: Fages regarded the Spanish installations in California as military institutions first, and religious outposts second.

- 1 2 3 4 Breschini, Ph.D., Gary S. (2000). "Mission San Carlos Borromeo (Carmel)". Monterey County Historical Museum. Retrieved 22 June 2013.

- 1 2 "Native Americans of San Carlos Borromeo de Carmelo". California Missions Resource Center. Retrieved 30 October 2015.

- ↑ Pritzker, Barry M. (2000). A Native American Encyclopedia: History, Culture, and Peoples. Oxford [u.a.]: Oxford Univ. Press. ISBN 978-0-19-513877-1.

- ↑ carmelmission.org, Mission History

- ↑ "San Carlos Borromeo de Carmelo". missionscalifornia.com.

- ↑ Edwards, Robert W. (2012). Jennie V. Cannon: The Untold History of the Carmel and Berkeley Art Colonies, Vol. 1. Oakland, Calif.: East Bay Heritage Project. pp. 523–525, 690. ISBN 9781467545679. An online facsimile of the entire text of Vol. 1 is posted on the Traditional Fine Arts Organization website (http://www.tfaoi.com/aa/10aa/10aa557.htm).

- ↑ http://www.carmelmission.org Museum/

- ↑ "Mission San Carlos de Borromeo de Carmelo". athanasius.com.

- ↑ "Californias-Missions.org: Mission San Carlos". californias-missions.org.

- ↑ "Junipero Serra School". juniperoserra.org.

Bibliography

- Forbes, Alexander (1839). California: A History of Upper and Lower California. Smith, Elder and Co., Cornhill, London.

- Jones, Terry L. and Kathryn A. Klar (eds.) (2007). California Prehistory: Colonization, Culture, and Complexity. AltaMira Press, Landham, MD. ISBN 0-7591-0872-2.

- Krell, Dorothy (ed.) (1979). The California Missions: A Pictorial History. Sunset Publishing Corporation, Menlo Park, CA. ISBN 0-376-05172-8.

- Leffingwell, Randy (2005). California Missions and Presidios: The History & Beauty of the Spanish Missions. Voyageur Press, Stillwater, MN. ISBN 0-89658-492-5.

- Paddison, Joshua (ed.) (1999). A World Transformed: Firsthand Accounts of California Before the Gold Rush. Heyday Books, Berkeley, CA. ISBN 1-890771-13-9.

- Ruscin, Terry (1999). Mission Memoirs. Sunbelt Publications, San Diego, CA. ISBN 0-932653-30-8.

- Smith, Frances Rand (1921). The Architectural History of Mission San Carlos Borromeo, California. California Historical Survey Commission, Berkeley, CA.

- Vancouver, George (1801). A Voyage of Discovery to the North Pacific Ocean and Round the World, Volume III. Printed for John Stockdale, Piccadilly, London.

- Yenne, Bill (2004). The Missions of California. Advantage Publishers Group, San Diego, CA. ISBN 978-0811836944.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mission San Carlos Borromeo de Carmelo. |

- Official Mission San Carlos Borromeo de Carmelo website

- Elevation & Site Layout sketches of the Mission proper

- Early photographs, sketches, land surveys of Carmel Mission, via Calisphere, California Digital Library

- Listing and photographs at the Historic American Buildings Survey

- Howser, Huell (December 8, 2000). "California Missions (105)". California Missions. Chapman University Huell Howser Archive.

- Photographs of the mission and courtyard

- Carmel Mission Cemetery at Find a Grave

- U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Mission San Carlos Borromeo de Carmelo