Missile gap

The missile gap was the Cold War term used in the US for the perceived superiority of the number and power of the USSR's missiles in comparison with its own. This gap in the ballistic missile arsenals only existed in exaggerated estimates made by the Gaither Committee in 1957 and in United States Air Force (USAF) figures. Even the contradictory CIA figures for the USSR's weaponry, which showed a clear advantage for the US, were far above the actual count. Like the bomber gap of only a few years earlier, it was soon demonstrated that the gap was entirely fictional.

John F. Kennedy is credited with inventing the term in 1958 as part of the ongoing election campaign, in which a primary plank of his rhetoric was that the Eisenhower administration was weak on defense. It was later learned that Kennedy was apprised of the actual situation during the campaign, which has led scholars to question what the (future) president knew and when he knew it. There has been some speculation that he was aware of the illusory nature of the missile gap from the start, and was using it solely as a political tool, an example of policy by press release.

Background

The Soviet launch of Sputnik 1 on 4 October 1957 highlighted the technological achievements of the Soviets and sparked some worrying questions for the politicians and general public of the USA. Although US military and civilian agencies were well aware of Soviet satellite plans, as they were publicly announced as part of the International Geophysical Year, Eisenhower's announcements that the event was unsurprising found little support among a US public still struggling with McCarthyism.

Political opponents seized on the event, and Eisenhower's ineffectual response, as further proof that the US was "fiddling as Rome burned." John F. Kennedy stated "the nation was losing the satellite-missile race with the Soviet Union because of … complacent miscalculations, penny-pinching, budget cutbacks, incredibly confused mismanagement, and wasteful rivalries and jealousies."[1] The Soviets capitalized on their strengthened position with false claims of Soviet missile capabilities, claiming on December 4, 1958, that "Soviet ICBMs are at present in mass production." Five days later on December 9th, Soviet Premier Nikita Kruschev boasted the successful testing of an ICBM with an impressive 8,000 mile range. [2] Coupled with the United States' failed launch of the Titan ICBM that month, a sense of Soviet superiority in missile technology became prevalent.

Inaccuracy of intelligence

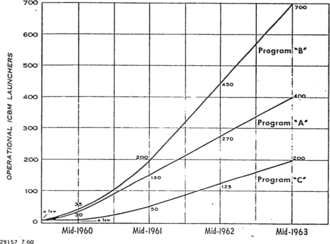

The National Intelligence Estimate (NIE) 11-10-57, issued in December 1957, predicted that the Soviets would "probably have a first operational capability with up to 10 prototype ICBMs" at "some time during the period from mid-1958 to mid-1959." The numbers started to inflate. A similar report gathered only a few months later, NIE 11-5-58 released in August 1958, concluded that the USSR had "the technical and industrial capability ... to have an operational capability with 100 ICBMs" some time in 1960, and perhaps 500 ICBMs "some time in 1961, or at the latest in 1962."[1]

Beginning with the collection of photo-intelligence by U-2 overflights of the Soviet Union in 1956, the Eisenhower administration had increasing hard evidence that claims of any strategic weapons favoring the Soviet Union were false. Based on this evidence, the CIA placed the number of ICBMs closer to a dozen. Continued sporadic flights failed to turn up any evidence of additional missiles. Curtis LeMay argued that the large stocks of missiles were in the areas not photographed by the U-2s, and arguments broke out over the Soviet factory capability in an effort to estimate their production rate.

In a widely syndicated article in 1959, Joseph Alsop even went so far as to describe "classified intelligence" as placing the Soviet missile count as high as 1,500 by 1963, while the US would have only 130 at that time.[3]

It is known today that even the CIA's estimate was too high; the actual number of ICBMs, even including interim-use prototypes, was 4.[4]

Playing for the public

In 1958 Kennedy was gearing up for his Senate re-election campaign and seized the issue. The Oxford English Dictionary lists the first use of the term "missile gap" on 14 August 1958 when he stated: "Our Nation could have afforded, and can afford now, the steps necessary to close the missile gap."[1] According to Robert McNamara, Kennedy was leaked the inflated USAF estimates by Senator Stuart Symington, the former Secretary of the Air Force. Unaware that the report was misleading, Kennedy used the numbers in the document and based some of his 1960 election campaign platform on the Republicans being "weak on defense".[5] The missile gap was a common theme.

Eisenhower refused to publicly refute the claims, fearing that public disclosure of this evidence would jeopardize the secret U-2 flights. Consequently, Eisenhower was frustrated by what he conclusively knew to be Kennedy's erroneous claims that the United States was behind the Soviet Union in number of missiles.[6] in an attempt to defuse the situation, Eisenhower arranged for Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson to be apprised of the information, first with a meeting by the Joint Chiefs of Staff, then Strategic Air Command, and finally with the Director of the CIA, Allen Dulles, in July 1960.[4] In spite of these meetings, Kennedy continued to use the same rhetoric, which modern historians have debated as likely being so useful to the campaign that he was willing to ignore the truth.[7]

In January 1961 McNamara, the new secretary of defense, and Roswell Gilpatric, a new deputy secretary who strongly believed in the existence of a missile gap, personally examined photographs taken by Corona satellites. Although the Soviet R-7 missile launchers were large and would be easy to spot in Corona photographs, they did not appear in any of them. In February McNamara stated that there was no evidence of a large-scale Soviet effort to build ICBMs. More satellite overflights continued to find no evidence, and by September 1961 a National Intelligence Estimate concluded that the USSR possessed no more than 25 ICBMs and would not possess more in the near future.[8] There was a missile gap, but it was greatly in the United States' favour, as it had already deployed substantial numbers of several varieties of land- and sea-based missiles.

During a transition briefing, Jerome Wiesner, "a member of Eisenhower's permanent Science Advisory Committee, … explained that the missile gap was a fiction. The new president greeted the news with a single expletive "delivered more in anger than in relief"[9] Kennedy was later embarrassed by the whole issue; the 19 April 1962 issue of The Listener noted "The passages on the 'missile gap' are a little dated, since Mr Kennedy has now told us that it scarcely ever existed."[10]

President Lyndon B. Johnson told a gathering in 1967:

"I wouldn't want to be quoted on this ... We've spent $35 or $40 billion on the space program. And if nothing else had come out of it except the knowledge that we gained from space photography, it would be worth ten times what the whole program has cost. Because tonight we know how many missiles the enemy has and, it turned out, our guesses were way off. We were doing things we didn't need to do. We were building things we didn't need to build. We were harboring fears we didn't need to harbor."

Effects

Warnings and calls to address imbalances between the fighting capabilities of two forces were not new, as a "bomber gap" had exercised political concerns a few years previously. What was different about the missile gap was the fear that a distant country could strike without warning from far away with little damage to themselves. Concerns about missile gaps and similar fears, such as nuclear proliferation, continue.

Promotion of the missile gap had several unintended consequences. The R-7 requires as much as 20 hours to be readied for launch, meaning that they could be easily attacked by bombers before they could strike. This demanded that they be based in secret locations to prevent a pre-emptive strike on them. As Corona could find these sites no matter where they were located, the Soviets decided not to build large numbers of R-7s, in favour of more advanced missiles that could be launched more quickly.[8]

Later evidence has emerged that one consequence of J.F Kennedy pushing the false idea that America was behind the Soviets in a missile gap was that Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev and senior Soviet military figures began to believe that Kennedy was a dangerous extremist who, with the American military, was seeking to plant the idea of a Soviet first-strike capability to justify a pre-emptive American attack. This belief about Kennedy as a militarist was reinforced in Soviet minds by the Bay of Pigs invasion of 1961 and led to the Soviets placing nuclear missiles in Cuba in 1962.

1970s

A second claim of a missile gap appeared in 1974. Albert Wohlstetter, a professor at the University of Chicago, accused the CIA of systematically underestimating Soviet missile deployment, in his 1974 foreign policy article entitled "Is There a Strategic Arms Race?" Wohlstetter concluded that the United States was allowing the Soviet Union to achieve military superiority by not closing a perceived missile gap. Many conservatives then began a concerted attack on the CIA's annual assessment of the Soviet threat.[11]

This led to an exercise in competitive analysis, with a group called Team B being created with the production of a highly controversial report.

According to then-Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, by 1976 the USA had a 6-to-1 advantage in the number of nuclear warheads over the Soviet Union.[12]

A 1979 briefing note on the National Intelligence Estimate (NIE) of the missile gap concluded that the NIE's record on estimating the Soviet missile force in the 1970s was mixed. The NIE estimates for initial operational capability (IOC) date for MIRVed ICBMs and SLBMs were generally accurate, as were the NIE predictions on the development of Soviet strategic air defenses. However, the NIE predictions also overestimated the scope of infrastructure upgrades in the Soviet system and underestimated the speed of Soviet improvement in accuracy and proliferation of re-entry vehicles. NIE results were regarded as improving but still vague, showing broad fluctuations and having little long-term validity.[13]

Popular culture

The whole idea of a missile gap was parodied in the 1964 film Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb in which a Doomsday device is built by the Soviets because they had read in The New York Times that the U.S. was working along similar lines and wanted to avoid a "Doomsday Gap". As the weapon is set up to go off automatically if the USSR is attacked, which is occurring as the movie progresses, the president is informed that all life on the surface will be killed off for a period of years. The only hope for survival is to select important people and place them deep underground in mine shafts until the radiation clears. The generals almost immediately begin to worry about a "mine shaft gap" between the US and Soviets. In reference to the alleged "missile gap" itself, General Turgidson mentions off-hand at one point that the United States actually has a five to one rate of missile superiority against the Soviet Union. The Russian ambassador himself also explains that one of the major reasons that the Soviets began work on the doomsday machine is that, ultimately, they realized that they simply could never match the rate of American military production (let alone outproduce American missile construction). The doomsday machine only cost a small fraction of what they normally spent on defense in a single year.

Missile Gap is also the title of a science fiction book by Charles Stross, which depicts an alternative resolution to the missile gap situation and subsequent Cuban Missile Crisis.

References

- 1 2 3 Preble, Christopher A. (December 2003). ""Who Ever Believed in the 'Missile Gap'?": John F. Kennedy and the Politics of National Security". Presidential Studies Quarterly. 33 (4): 801–826. doi:10.1046/j.0360-4918.2003.00085.x.

- ↑ Pedlow, Gregory W.; Welzenbach, Donald E. (1992). The Central Intelligence Agency and Overhead Reconnaissance. History Staff; Central Intelligence Agency. pp. 159–160.

- ↑ Joseph Alsop, "True Missile Gap Picture Belies Pentagon Response", Eugene Register-Guard, 13 October 1959

- 1 2 Dwane Day, Of myths and missiles: the truth about John F. Kennedy and the Missile Gap, The Space Review, 3 January 2006

- ↑ CNN Cold War - Interviews: Robert McNamara Archived December 5, 2008, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Smith, Jean Edward (2012). Eisenhower in War and Peace. Random House. p. 734. ISBN 978-0-679-64429-3.

- ↑ Donaldson, Gary (2007). The First Modern Campaign: Kennedy, Nixon, and the Election of 1960. p. 128.

- 1 2 Heppenheimer, T. A. (1998). The Space Shuttle Decision. NASA. pp. 195–197.

- ↑ Preble, Christopher A. (December 2003). "Who Ever Believed in the 'Missile Gap'?": John F. Kennedy and the Politics of National Security"". Presidential Studies Quarterly: 816,819 ). … Herken, 140. This quote taken from Herken's interview with Wiesner conducted 9 February 1982.

- ↑ "Excerpts from the BBC on ABM", Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, January 1968

- ↑ Barry, Tom (February 12, 2004). "Remembering Team B". International Relations Center. Archived from the original on 14 February 2004.

- ↑ "Memorandum of Conversation: J. Malcolm Fraser, Prime Minister of Australia, President Ford, Dr. Henry A. Kissinger, Secretary of State, et al." (PDF). The White House. July 27, 1976. Retrieved 2011-01-03.

- ↑ "NIE Track Record" (PDF). DCI Backup Briefing Note. July 11, 1979. Retrieved 19 February 2014.