Pogo (comic strip)

| Pogo | |

|---|---|

|

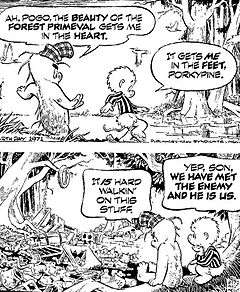

Pogo daily strip from Earth Day, 1971 | |

| Author(s) | Walt Kelly |

| Current status / schedule | Concluded |

| Launch date | 4 October 1948 (as a newspaper strip) |

| End date | 20 July 1975 |

| Syndicate(s) | Post-Hall Syndicate |

| Publisher(s) | Simon & Schuster, Fantagraphics Books, Gregg Press, Eclipse Comics, Spring Hollow Books |

| Genre(s) | Humor, Satire, Politics |

Pogo is the title and central character of a long-running daily American comic strip, created by cartoonist Walt Kelly (1913–1973) and distributed by the Post-Hall Syndicate. Set in the Okefenokee Swamp of the southeastern United States, the strip often engaged in social and political satire through the adventures of its anthropomorphic funny animal characters.

Pogo combined both sophisticated wit and slapstick physical comedy in a heady mix of allegory, Irish poetry, literary whimsy, puns and wordplay, lushly detailed artwork and broad burlesque humor. The same series of strips can be enjoyed on different levels by both young children and savvy adults. The strip earned Kelly a Reuben Award in 1951.

History

Walter Crawford Kelly, Jr. was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, on August 25, 1913. His family moved to Bridgeport, Connecticut, when he was only two. He went to California at age 22 to work on Donald Duck cartoons at Walt Disney Studios in 1935. He stayed until the animators' strike in 1941 as an animator on The Nifty Nineties, The Little Whirlwind, Pinocchio, Fantasia, Dumbo and The Reluctant Dragon. Kelly then worked for Dell Comics, a division of Western Publishing of Racine, Wisconsin.

Dell Comics

Kelly created the characters of Pogo the possum and Albert the alligator in 1941 for issue #1 of Dell's Animal Comics, in the story "Albert Takes the Cake".[1] Both were comic foils for a young black character named Bumbazine (a corruption of bombazine, a fabric that was usually dyed black and used largely for mourning wear), who lived in the swamp. Bumbazine was retired early, since Kelly found it hard to write for a human child. He eventually phased humans out of the comics entirely, preferring to use the animal characters for their comic potential. Kelly said he used animals — nature's creatures, or "nature's screechers" as he called them — "largely because you can do more with animals. They don't hurt as easily, and it's possible to make them more believable in an exaggerated pose." Pogo, formerly a "spear carrier" according to Kelly, quickly took center stage, assuming the straight man role that Bumbazine had occupied.

The New York Star

In his 1954 autobiography for the Hall Syndicate, Kelly said he "fooled around with the Foreign Language Unit of the Army during the war, illustrating grunts and groans, and made friends in the newspaper and publishing business." In 1948 he was hired to draw political cartoons for the editorial page of the short-lived New York Star; he decided to do a daily comic strip featuring the characters from Animal Comics. The first comic series to make the permanent transition to newspapers, Pogo debuted on October 4, 1948, and ran continuously until the paper folded on January 28, 1949.

Syndication

On May 16, 1949, Pogo was picked up for national distribution by the Post-Hall Syndicate. George Ward and Henry Shikuma were among Kelly's assistants on the strip. It ran continuously until (and past) Kelly's death from complications of diabetes on October 18, 1973. It was then continued for a few years by Kelly's widow Selby and son Stephen, before ceasing publication July 20, 1975. Selby Kelly said in a 1982 interview that she decided to discontinue the strip, because newspapers had shrunk the size of strips to the point where people could not easily read it.[2]

Cast of characters

Kelly's characters are a sardonic reflection of human nature —venal, greedy, confrontational, selfish and stupid —but portrayed good-naturedly and rendered harmless by their own bumbling ineptitude and overall innocence. Most characters were nominally male, but a few female characters also appeared regularly. Kelly has been quoted as saying that all the characters reflected different aspects of his own personality. Kelly's characters were also self-aware of their comic strip surroundings.[3] He frequently had them leaning up against or striking matches on the panel borders, breaking the fourth wall, or making tongue-in-cheek, "inside" comments about the nature of comic strips in general.

It's difficult to compile a definitive list of every character that appeared in Pogo over the strip's 27 years, but the best estimates put the total cast at well over 1,000. Kelly created characters as he needed them, and discarded them after they served their purpose. Occasionally he reintroduced characters under different names (such as Mole or Curtis) and other inconsistencies, reflecting the fluid quality of the strip. Kelly continually tinkered with his creation to suit either his whims or the current storyline. Even though most characters have full names, some are more often referred to only by their species. For example, Howland Owl is almost always called "Owl" or "ol' Owl," Beauregard is often called "Houn' Dog," Churchy LaFemme is sometimes called "Turtle" or "Turkle" (see Dialogue and "swamp-speak"), etc. The following list is necessarily incomplete, but should serve as a rough beginner's guide:

Permanent residents

- Pogo Possum: An amiable, humble, philosophical, personable, everyman opossum. Kelly described Pogo as "the reasonable, patient, softhearted, naive, friendly person we all think we are" in a 1969 TV Guide interview.[4] The wisest (and probably sanest) resident of the swamp, he is one of the few major characters with sense enough to avoid trouble. Though he prefers to spend his time fishing or picnicking, his kind nature often gets him reluctantly entangled in his neighbors' escapades. He is often the unwitting target of matchmaking by Miz Beaver (to the coquettish Ma'm'selle Hepzibah), and has repeatedly been forced by the swamp's residents to run for president, always against his will. He wears a simple red and black striped shirt and (sometimes) a crushed yellow fishing hat. His kitchen is well-known around the swamp for being fully stocked, and many characters impose upon him for meals, taking advantage of his generous nature. His full name is Ponce de Leon Montgomery County Alabama Georgia Beauregard Possum —a parody of the blueblood aristocracy of the Old South.

- Albert Alligator: Exuberant, dimwitted, irascible and egotistical, Albert is often the comic foil for Pogo, the rival of Beauregard and Barnstable, or the fall guy for Howland and Churchy. The cigar-chomping Albert is as extroverted and garrulous as Pogo is modest and unassuming, and their many sequences together tend to underscore their balanced, contrasting chemistry —like a seasoned comedy team. Albert's creation actually preceded Pogo's, and his brash, bombastic personality sometimes seems in danger of taking over the strip, as he once dominated the comic books. Having an alligator's voracious appetite, Albert often eats things indiscriminately, and is accused on more than one occasion of having eaten another character. Albert is the troop leader of Camp Siberia, the local den of the "Cheerful Charlies" (Kelly's version of the Boy Scouts), whose motto is "Cheerful to the Death!" Even though Albert has been known to take advantage of Pogo's generosity, he is ferociously loyal to Pogo and will, in quieter moments, be found scrubbing him in the tub or cutting his hair. Like all Kelly's characters, Albert looks great in costume. This sometimes leads to a classic Albert line (while admiring himself in a mirror): "Funny how a good-lookin' fella look handsome in anything he throw on!"

- Howland Owl: The swamp's self-appointed leading authority, a self-proclaimed "expert" scientist, "perfessor," physician, explorer, astronomer, witch doctor, and anything else he thinks will generate respect for his knowledge. He wears horn-rimmed eyeglasses and, in his earliest appearances, a pointed wizard's cap festooned with stars and crescent moons (which also, fittingly, looks like a dunce cap in silhouette.) Thinking himself the most learned creature in the swamp, he once tried to open a school but had to close it for lack of interest. Actually he is unable to tell the difference between learning, old wives' tales, and the use of big words. Most of the harebrained ideas characteristically come from the mind of Owl. His best pal is Churchy, although their friendship can be rocky at times, often given to whims and frequently volatile.

- Churchill "Churchy" LaFemme: A mud turtle by trade; he enjoys composing songs and poems, often with ridiculous and abrasive lyrics and nonsense rhymes. His name is a play on the French phrase Cherchez la femme, ("Look for the woman"). Perhaps the least sensible of the major players, Churchy is superstitious to a fault, for example, panicking when he discovers that Friday the 13th falls on a Wednesday that month. Churchy is usually an active partner in Howland's outlandish schemes, and prone to (sometimes physical) confrontation with him when they (inevitably) run afoul. Churchy first appeared as buccaneer in Animal Comics #13 (Feb 1945), with a pirate's hat. He was sometimes referred to as "Cap'n LaFemme." This seems incongruous for the guileless Churchy, however, who is far more likely to play-act with Owl at being a pantomime pirate than the genuine article.

- Beauregard Bugleboy: A hound dog of undetermined breed; scion of the Cat Bait fortune and occasional Keystone Cops-attired constable and Fire Brigade chief. He sees himself as a noble, romantic figure, often given to flights of oratory while narrating his own heroic deeds (in the third person). He periodically appears with "blunked out" eyes playing "Sandy" —alongside Pogo or Albert when they don a curly wig, impersonating "Li'l Arf an' Nonny," (a.k.a. "Lulu Arfin' Nanny," Kelly's recurring parody of Little Orphan Annie). Beauregard also occasionally dons a trench coat and fedora, and squints his eyes and juts out his jaw when impersonating a detective in the style of Dick Tracy. However, his more familiar attire is a simple dog collar — or in later strips, a striped turtleneck sweater and fez. His canine revision of Kelly's annual Christmas burlesque, Deck Us All with Boston Charlie, emerges as "Bark Us All Bow-wows of Folly," [5] although he can't get anyone else to sing it that way. Usually just called "Beauregard" or "ol' Houn' Dog," his full name is Beauregard Chaulmoogra Frontenac de Montmingle Bugleboy.

- Porky Pine: A porcupine, a misanthrope and cynic; prickly on the outside but with a heart of gold. The deadpan Porky never smiles in the strip (except once, allegedly, when the lights were out). Pogo's best friend, equally honest, reflective and introverted, and with a keen eye both for goodness and for human foibles. The swamp's version of Eeyore, Porkypine is grumpy and melancholy by nature, and sometimes speaks of his "annual suicide attempt." He wears an undersized, plaid Pinky Lee-type hat (with an incongruously tall crown and upturned brim) and a perpetual frown, and is rarely seen without both. Porky has two weaknesses: his infatuation for Miz Mam'selle Hepzibah and a complete inability to tell a joke. He unfailingly arrives on Pogo's doorstep with a flower every Christmas morning, although he's always as embarrassed by the sentiment as Pogo is touched. He has a nephew named Tacky and a look-alike relation (see Frequent visitors) named Uncle Baldwin.

- Miz Ma'm'selle Hepzibah: A beautiful, coy French skunk modeled after Kelly's mistress, who later became his second wife. Hepzibah has long been courted by Porky, Beauregard and others but rarely seems to notice. Sometimes she pines for Pogo, and isn't too shy about it. She speaks with a heavy burlesque French dialect and tends to be overdramatic. The unattached Hepzibah has a married sister with 35 youngsters, including a nephew named Humperdunk. She is captivatingly sweet, frequently baking pies or preparing picnic baskets for her many admirers, and has every fellow in the swamp in love with her at one time or another. She is usually attired in a dainty floral skirt and parasol, is flirty but proper, and enjoys attention.

- Miz Beaver: A no-nonsense, corncob pipe-smoking washerwoman; a traditional mother (she is frequently seen minding a perambulator, her pet fish, or a tadpole in a jar) and "widder" (she occasionally speaks of "the Mister," always in the past tense), clad in a country bonnet and apron. Uneducated but with homespun good sense, she "takes nothin' from nobody," and can be daunting when riled. She is Hepzibah's best friend and occasional matchmaker, although she disapproves of menfolk as a general rule. Her trademark line is: "WHY is all you mens such critturs of dee-ceit?"

- Deacon Mushrat: A muskrat and the local man of the cloth, the Deacon speaks in ancient blackletter text or Gothic script, and his views are just as modern. He is typically seen haranguing others for their undisciplined ways, attempting to lead the Bats in some wholesome activity (which they inevitably subvert), or reluctantly entangled in the crusades of Mole and his even shadier allies — in either role he is the straight man and often winds up on the receiving end of whatever scheme he is involved in. Kelly described him as the closest thing to an evil character in the strip, calling him "about as far as I can go in showing what I think evil to be."[6]

- Bewitched, Bothered and Bemildred: A trio of grubby, unshaven bats — hobos, gamblers, good-natured but innocent of any temptation to honesty. They admit nothing. Soon after arriving in the swamp they are recruited by Deacon Mushrat into the "Audible Boy Bird Watchers Society," (a seemingly innocent play on the Audubon Society, but really a front for Mole's covert surveillance syndicate.) They wear identical black derby hats and perpetual 5 o'clock shadows. Their names, a play on the song title Bewitched, Bothered and Bewildered, are rarely mentioned. Often even they cannot say for sure which brother is which. They tell each other apart, if at all, by the patterns of their trousers — striped, checkered or plaid. (According to one of the bats, "Whichever pair of trousers you puts on in the morning, that's who you are for that partic'lar day.")

- Barnstable Bear: A simple-minded, henpecked "grizzle bear" who often plays second-fiddle to many of Albert's plots. He wears a pair of pants held up with a single suspender, and often a checkered cloth cap. Frequently short-tempered (and married to an even shorter-tempered "missus," the formidable Miz Bear), he bellows "Rowrbazzle!" when his anger comes to a boil. Barnstable even tried to start his own rival comic strip in 1958, which he entitled "Little Orphan Abner" (with a wink to Kelly's pal, fellow cartoonist Al Capp), just to spite Albert.

- Mister Miggle: A bespectacled stork or crane, and proprietor of the local general store, a frequent swamp hangout. He dresses like an old-fashioned "country" clerk — with apron, starched collar, suspenders, sleeve garters, and a straw boater or a bookkeeping visor. Miggle's carries just about every undesirable product imaginable, such as "Salt fish in chocolate sauce" and "Day-old ice, 25¢ per gallon," along with "Aunt Granny's Bitter Brittle Root" — a local favorite beverage (after sassafras tea), and cure-all for the "cold robbies" and the "whim-whams."

- Bun Rab: An enthusiastic white rabbit with a drum and drum-major hat who often accompanies P. T. Bridgeport and likes to broadcast news in the manner of a town crier. He lives in a grandfather clock, and frequently appears as a fireman in the swamp's clownish Fire Brigade — where he serves as official hose carrier.

- Rackety Coon Chile: One of the swamp "sprats" — a group of youngsters who seem to be the only rational creatures present, other than Pogo and Porky. A talkative, precocious raccoon, he mainly pesters his "uncle" Pogo, along with his pal Alabaster. His parents, Mr. and Mrs. Rackety Coon, are a bickering couple occasionally featured. The father ("Pa") owns a still, and is generally suspicious of Ma's going through his overalls pockets while he sleeps.

- Alabaster Alligator: Not much is known about Alabaster except that he is considerably brighter than his Uncle Albert. Genial, inquisitive and only occasionally mischievous, he follows the cartoon tradition of the look-alike nephew (see Huey, Dewey, and Louie) whose mysterious parental lineage is never made specific.

- Grundoon: A diapered baby groundhog (or "woodchunk" in swamp-speak). An infant toddler, Grundoon speaks only gibberish, represented by strings of random consonants like "Bzfgt," "ktpv," "mnpx," "gpss," "twzkd," or "znp." Eventually, Grundoon learns to say two things: "Bye" and "Bye-bye." He also has a baby sister, whose full name is Li'l Honey Bunny Ducky Downy Sweetie Chicken Pie Li'l Everlovin' Jelly Bean.

- Pup Dog: An innocent "li'l dog chile" puppy. One of the very few characters who walks on all fours, he frequently wanders off and gets lost. Being, as Pogo puts it, "'jus' a li'l ol' shirt-tail baby-size dog what don't talk good yet," he says only "Wurf!" and "Wurf wurf!," although for a time he repeats the non sequitur phrase "Poltergeists make up the principal type of spontaneous material manifestation."

Frequent visitors

- P. T. Bridgeport: A bear; a flamboyant impresario and traveling circus operator named after P. T. Barnum, the most famous resident of Kelly's boyhood home, Bridgeport, Connecticut. One of Kelly's most colorful characters, P. T. wears a straw boater, spats, vest, ascot tie with stickpin and outlandish, fur-lined plaid overcoat reminiscent of W. C. Fields. There is also sometimes a marked physical resemblance to the Dutch cartoon character Oliver B. Bumble. An amiable blowhard and charlatan, his speech balloons resemble 19th-century circus posters, symbolizing both his theatrical speech pattern and his customary carnival barker's sales spiel. He usually visits the swamp during presidential election years, satirizing the media circus atmosphere of American political campaigns. During the storyline in which Pogo was nominated as a presidential candidate, Bridgeport was his most vocal and enthusiastic supporter.

- Tammananny Tiger: A political operator, named in allusion to Tammany Hall, which was represented as a tiger in 19th century editorial cartoons by Thomas Nast. He typically appears in election years to offer strategic advice to the reluctant candidate, Pogo. He first appears as a companion to P. T. Bridgeport, although more cynical and less self-aggrandizing than the latter, and is one of only a handful of animals not native to North America to frequent the swamp.

- Mole (in his original appearance in 1952 named Mole MacCarony, in later years sometimes called Molester Mole, his name pronounced not "molester" but, in keeping with his political aspirations, to rhyme with "pollster"): A nearsighted and xenophobic grifter. Considers himself an astute observer, but walks into trees without seeing them. Obsessed with contagion both literal and figurative, he is a prime mover in numerous campaigns against "subversion," and in his first appearances has a paranoid habit of spraying everything and everyone with a disinfectant that may have been liberally laced with tar. Modeled somewhat after Senator Pat McCarran of the McCarran–Walter Act.[7]

- Seminole Sam: A mercenary, carpetbagging fox and traveling huckster of the snake oil salesman variety. He often attempts to swindle Albert and others, for example by selling bottles of the "miracle fluid" H2O. Sam isn't really an out-and-out villain – more of an amoral opportunist, even though he occasionally allies with darker characters such as Mole and Wiley. Sam's Seminole moniker probably refers, not to any native blood ties, but more likely to a presumed history of selling bogus patent medicine ("snake oil"). These "salesmen" hucksters often pretended their products were tested and proven, ancient Indian remedies. The Seminoles are an Indian tribe in the neighborhood of Okefenokee Swamp.

- Sarcophagus MacAbre: A buzzard and the local mortician. He lives in a creepy, ruined mausoleum, and always wears a tall undertaker's stove pipe hat with a black veil hung from its side. Early strips show him speaking in square, black bordered speech balloons with ornate script lettering, in the style of Victorian funeral announcements. MacAbre begins as a stock villain, but in later years gradually softens into a somewhat befuddled comic foil.

- The Cowbirds: Two beatnik freeloaders, their gender(s) uncertain, who speak in communist cant (albeit often in typical Okefenokee patois) and grift any food and valuables that cross their path. They associate with a pirate pig who resembles Nikita Khrushchev. Later they loudly renounce their former beliefs — without changing their behavior much. They typically address each other as Compeer and Confrere. It's unclear whether these are proper names or titles (synonyms of Comrade).

- Wiley Catt: A wild-eyed, menacing, hillbilly bobcat who smokes a corncob pipe, carries a shotgun, and lives alone in a dilapidated, Tobacco Road-type shanty on the outskirts of the swamp. He frequently hangs out with Sarcophagus MacAbre, Mole and Seminole Sam, although none of them trusts him. All the swamp critters are rightly wary of him, and generally give him a wide path. During the "Red scare" era of the 1950s, he temporarily morphed into his "cousin" Simple J. Malarkey, a parody and caricature of Republican senator from Wisconsin, Joseph McCarthy (see Satire and politics).

- Miss Sis Boombah: A matronly, cheerleading Rhode Island Red hen, who is a gym coach and fitness enthusiast — as well as a close friend of Miz Beaver — usually attired in tennis shoes and a pullover. Boombah arrives at the swamp to conduct a survey for "Dr. Whimsy" on "the sectional habits of U.S. mailmen," a neat parody of The Kinsey Reports. She also runs a Feminist organization (with Miz Beaver) called "F.O.O.F." (Female Order Of Freedom), to un-subjugate the swamp womenfolk.

- Ol' Mouse: An otherwise unnamed, long-winded, worldly mouse with a bowler hat, cane and cigar who frequently pals around with Snavely, the Flea, Albert, or Pup Dog, the last of whom he was briefly imprisoned with in a cupboard and with whom he forged a bond as a fellow prisoner. He has a long and storied career as a rogue, in which he takes some pride, noting that the crimes he has been falsely accused of are far less interesting than the crimes he has actually committed. He is more often an observer and commentator than an actual participant in storylines. Something of a dandy, he sometimes takes the name "F. Olding Munny" — but only when Albert is posing as swami "El Fakir," (a take-off on Daddy Warbucks and his Indian manservant Punjab from Little Orphan Annie).

- Snavely: A chatty, inebriated snake (he is prone to biting himself, then dipping into a bottle of "snake bite remedy"). Snavely usually wears a battered top hat, and pals around with Ol' Mouse or a group of angleworms that he is training to be cobras or rattlesnakes. In classic cartoon tradition, his intoxicated state is portrayed by a prominent red nose surrounded by tiny, fizzing bubbles. Although limbless, he is able to salute. Pogo saw this and was amazed. Unfortunately this act was accomplished behind the log Pogo was looking over, and the reader's view was blocked.

- Choo Choo Curtis (a.k.a. Chug Chug Curtis): A natural-born mail carrier duck.

- Uncle Baldwin: Porky's doppelgänger and compulsive "kissing cousin", he wears a trenchcoat to hide his telltale bald backside. Uncle Baldwin usually tries to grab and kiss any female in the panel with him. Most of the females (and more than a few of the male characters) flee from the scene when Uncle Baldwin arrives. When assaulted by him, Hepzibah has hit him back.

- Reggie and Alf: Two Cockney insects that wander around bickering and looking for cricket matches. Kelly loved definite personality types, and had these two show up occasionally, even though they had nothing to do with anything else. Kelly stated the aim of their appearance, "was to please nobody but me".

- Flea (a.k.a. Miz Flea): An unnamed female flea, so small she is usually only drawn in black silhouette. She falls in love with Beauregard, calls him "doll" and "sugar," and frequently gives him love nips on the nose or knee – much to his indignant irritation. (Flea: "Two can live as cheap as one, sugar." Beauregard: "Not on me, they can't!") Her gender was vaguely indeterminate for much of the run of the strip, but in a 1970 sequence with ex-husband Sam the spider, the Flea is finally and definitively established as a "girl". Thereafter, she is occasionally addressed as "Miz". In The Pogopedia (2001), this character is identified as "Ol' Flea".

- Fremount the Boy Bug: The swamp's dark horse candidate, whose limited vocabulary (all he can say is "Jes' fine") makes him suitable presidential timber, according to P. T. Bridgeport.

- Bug Daddy and Chile: Daddy's indignant tag-line ("Destroy a son's faith in his father, will you?") invariably follows his being corrected by another character for an (inevitable) misunderstanding or erroneous explanation on his part. He wears a stove pipe hat and carries an umbrella, which he shakes threateningly at the slightest provocation. His boy's name is ever-changing, even from panel to panel within the same strip: Hogblemish, Nortleberg, Flimplock, Osbert, Jerome, Merphant, Babnoggle, Custard, Lorenzo, etc. (The Pogopedia identifies these characters as "Bug Daddy" and "Bug Child.")

- Congersman Frog: An elected official, usually accompanied by his look-alike male secretary, with whose pay he lights his "seegars." He practices disavowing his candidature for the presidency — not very convincingly. His seldom-used first name is Jumphrey, and his secretary/sidekick was occasionally referred to by name: Fenster Moop. (Fenster apparently rose to Congress himself. In later years he's addressed as "Congersman," and attended by his own look-alike secretary, Feeble E. Merely.)

- Solid MacHogany: A New Orleans-bound, clarinet-playing pig in a polka dot cap and striped necktie, headed to a paying gig in a "sho' nuff" jazz band on Bourbon Street.

- Horrors Greeley: A freckled, westward-traveling cow (hence the reference to Horace Greeley), who was sweet on Albert. (To Horrors, "west" being Milwaukee.)

- Uncle Antler: A disagreeable bullmoose, whom Albert insultingly addresses as "Hatrack."

- Butch: A brick-throwing housecat. Like Tammananny, Butch is a direct homage to another cartoonist — George Herriman, whose Krazy Kat comic strip was greatly admired by Kelly. Butch feels compelled to hurl bricks at Beauregard, in honor of the traditional animus between dogs and cats. He always deliberately misses, however — and after his initial appearance as an antagonistic rival, proves to be something of a pussycat.

- Basil MacTabolism: A door-to-door political pollster polecat and self-described "taker of the public pulse."

- Roogey Batoon: A part-time snake oil salesman pelican in a flat cap, who claims to have made the careers of the "Lou'siana Perches", (an underwater songstress trio named Flim, Flam and Flo). His name is a play on Baton Rouge, Louisiana.

- Picayune: A talkative frog that is a "free han' pree-dicter of all kinds weather an' other social events — sun, hail, moonshine or ty-phoonery". (An identical frog known as Moonshine Sonata also appears on occasion; it is unclear if these were intended to be the same character.)

Setting

Pogo is set in the Georgia section of the Okefenokee Swamp; Fort Mudge and Waycross are occasionally mentioned.

The characters live, for the most part, in hollow trees amidst lushly rendered backdrops of North American wetlands, bayous, lagoons and backwoods. Fictitious local landmarks — such as "Miggle’s General Store and Emporium" (a.k.a. "Miggle's Miracle Mart") and the "Fort Mudge Memorial Dump," etc. — are occasionally featured. The memorial dump was destroyed in an inferno caused by Owl's disastrous attempt to launch a rocket ship, in the strips from 27 April 1990 to 18 May 1990, and was under reconstruction when the strip terminated. The landscape is fluid and vividly detailed, with a dense variety of (often caricatured) flora and fauna. The richly textured trees and marshlands frequently change from panel to panel within the same strip. Like the Coconino County depicted in Krazy Kat and the Dogpatch of Li'l Abner, the distinctive cartoon landscape of Kelly’s Okefenokee Swamp became as strongly identified with the strip as any of its characters.

Early in the strip, human artifacts have appeared: a hi-tension wire pylon, a boxcar and such.

There are occasional forays into exotic locations as well, including at least two visits to Australia (during the Melbourne Olympics in 1956, and again in 1961). The Aussie natives include a bandicoot, a lady wallaby, and a mustachioed, aviator kangaroo named "Basher". In 1967, Pogo, Albert and Churchy visit primeval "Pandemonia" — a vivid, "prehysterical" place of Kelly’s imagination, complete with mythical beasts (including dragons and a zebra-striped unicorn), primitive humans, arks, volcanoes, saber-toothed cats, pterodactyls and dinosaurs.

Kelly also frequently parodied Mother Goose stories featuring the characters in period costume: "Cinderola," "Goldie Lox and the Fore-bears," "Handle and Gristle," etc. These offbeat sequences, usually presented as a staged play or a story-within-a-story related by one of the characters, seem to take place in the fairy tale dreamscapes of children’s literature, with European storybook-style cottages and forests, etc.—rather than in the swamp, per se.

Dialogue and "swamp-speak"

The strip was notable for its distinctive and whimsical use of language. Kelly, a native northeasterner, had a sharply perceptive ear for language and used it to great humorous effect. The predominant vernacular in Pogo, sometimes referred to as "swamp-speak," is essentially a rural southern U.S. dialect laced with nonstop malapropisms, fractured grammar, "creative" spelling and mangled polysyllables such as "incredibobble" and "hysteriwockle," plus invented words such as the exasperated exclamations "Bazz Fazz!," "Rowrbazzle!" and "Moomph!"[8] The resulting dialect is difficult to characterize, but the following fragment of dialogue[9] may convey the general flavor:

Pogo has been engaged in his favorite pastime, fishing in the swamp from a flat-bottomed boat, and has hooked a small catfish. "Ha!" he exclaims, "A small fry!" At this point Hoss-Head the Champeen Catfish, bigger than Pogo himself, rears out of the swamp and the following dialogue ensues:

- Hoss-Head [with fins on hips and an angry scowl]: Chonk back that catfish chile, Pogo, afore I whops you!

- Pogo: Yassuree, Champeen Hoss-Head, yassuh yassuh yassuh yassuh yassuh ... [tosses infant catfish back in water]

- Pogo [walks away, muttering discontentedly]: Things gettin' so humane 'round this swamp, us folks will have to take up eatin' MUD TURKLES!

- Churchy (a turtle) [eavesdropping from behind a tree with Howland Owl]: Horroars! A cannibobble! [passes out]

- Howland [holding the unconscious Churchy]: You say you gone eat mud turkles! Ol' Churchy is done overcame!

- Pogo: It was a finger of speech—I apologize! Why, I LOVES yo', Churchy LaFemme!

- Churchy [suddenly recovered from his swoon]: With pot licker an' black-eye peas, you loves me, sir—HA! Us is through, Pogo!

Nonsense verse and song parodies

Kelly was an accomplished poet, and frequently added pages of original comic verse to his Pogo reprint books, complete with charming cartoon illustrations. The odd song parody or nonsense poem also occasionally appeared in the newspaper strip. In 1956, Kelly published Songs of the Pogo, an illustrated collection of his original songs, with lyrics by Kelly and music by Kelly and Norman Monath. The tunes were also issued on a vinyl LP, with Kelly himself contributing to the vocals.

Traditional Christmas carols were a regular feature of Kelly's holiday strips as well — particularly Deck the Halls. They are enthusiastically performed by the swamp's rotating "Okefenokee Glee and Perloo Union" Choir (perloo is a pilaf-based Cajun stew, similar to jambalaya), although in their childish innocence the chorus typically mangles the lyrics. (Churchy once sang a version of Good King Wenceslas that went: "Good King Sauerkraut look out / On his feets uneven / Beware the snoo lay 'round about / All kerchoo achievin' ...")

Satire and politics

Kelly used Pogo to comment on the human condition, and from time to time, this drifted into politics. Pogo was a reluctant "candidate" for President (although he never campaigned) in 1952 and 1956. (The phrase "I Go Pogo," originally a parody of Dwight D. Eisenhower's iconic campaign slogan "I Like Ike," appeared on giveaway promotional lapel pins featuring Pogo, and was also used by Kelly as a book title.) A 1952 campaign rally at Harvard degenerated into chaos sufficient to be officially termed a riot, and police responded. The Pogo Riot was a significant event for the class of ’52; for its 25th reunion, Pogo was the official mascot.[10] In 1960 the swamp's nominal candidate was an egg with two protruding webbed feet — a comment on the relative youth of John F. Kennedy. The egg kept saying: "Well, I've got time to learn; we rabbits have to stick together."

Kelly, who claimed to be against "the extreme Right, the extreme Left, and the extreme Middle," used these fake campaigns as excuses to hit the stump himself for voter registration campaigns, with the slogan "Pogo says: If you can't vote my way, vote anyway, but VOTE!"

Simple J. Malarkey

Perhaps the most famous example of the strip's satirical edge came into being on May 1, 1953, when Kelly introduced a friend of Mole's: a wildcat named "Simple J. Malarkey," an obvious caricature of Senator Joseph McCarthy. This showed significant courage on Kelly's part, considering the influence the politician wielded at the time and the possibility of scaring away subscribing newspapers.[11]

When The Providence Bulletin issued an ultimatum in 1954, threatening to drop the strip if Malarkey's face appeared in the strip again, Kelly had Malarkey throw a bag over his head as Miss "Sis" Boombah (a Rhode Island Red hen) approached, explaining "no one from Providence should see me!" Kelly thought Malarkey's new look was especially appropriate because the bag over his head resembled a Klansman's hood.[12] (Kelly later attacked the Klan directly, in a comic nightmare parable called "The Kluck Klams," included in The Pogo Poop Book, 1966.)

Malarkey appeared in the strip only once after that sequence ended, during Kelly's tenure, on October 15, 1955. Again his face was covered, this time by his speech balloons as he stood on a soapbox shouting to general uninterest. Kelly had planned to defy the threats made by the Bulletin and show Malarkey's face, but decided it was more fun to see how many people recognized the character and the man he lampooned by speech patterns alone. When Kelly got letters of complaint about kicking the senator when he was down (McCarthy had been censured by that time, and had lost most of his influence), Kelly responded, "They identified him, I didn't." [13]

Malarkey reappeared on 4-1-1989 when the strip had been resurrected by Larry Doyle and Neal Sternecky. It was hinted that he was a ghost.

The Jack Acid Society

In the early 1960s, Kelly took on the ultra-conservative John Birch Society with a series of strips dedicated to Mole and Deacon's efforts to weed out Anti-Americanism (as they saw it) in the swamp, which led them to form "The Jack Acid Society." ("Named after Mr. Acid?" "Well, it wasn't named before him.") The reference is to John Birch, who was killed 13 years before the creation (in 1958) of the organization that bears his name. The Jack Acids (the name is an obvious pun on "jackasses") modeled themselves on the only "real" Americans: Indians. Everyone the Jack Acids suspected of not being a true American was put on their blacklist, until eventually everyone but Mole himself was blacklisted. One of the longest-running storylines in the strip's history, the strips were collected by themselves (with some original verse and text pieces) in The Jack Acid Society Black Book, the only Pogo collection not to include the main character's name in the title[14] and one of only two books (the other being Pogo: Prisoner Of Love) to comprise a single storyline.

Later politics

As the 1960s loomed, even foreign "gummint" figures found themselves caricatured in the pages of Pogo, including communist leaders Fidel Castro, who appeared as an agitator goat named Fido, and Nikita Khrushchev, who emerged as both an unnamed Russian bear and a pig. Other Soviet characters include a pair of cosmonaut seals who arrive at the swamp in 1961 via Sputnik, initiating a topical spoof of the Space Race. An obtuse feline reporter from Newslife magazine named Typo, who resembled both Barry Goldwater and Nelson Rockefeller, arrived on the scene in 1966. He was often accompanied by a chicken photographer named Hypo, wearing a jaunty fedora with a Press tag in the hat band, and carrying a box camera with an extremely droopy accordion bellows.

By the time the 1968 presidential campaign rolled around, it seemed the entire swamp was populated by P. T. Bridgeport's "wind-up candidates," including representations of George Romney, Richard Nixon, Hubert Humphrey, Robert F. Kennedy and George Wallace as wind-up toys. Wallace also appeared as The Prince of Pompadoodle, a puffed-up, diminutive rooster chick. Eugene McCarthy was a white knight tied backwards on his horse, spouting poetry. Retiring President Lyndon B. Johnson was portrayed as a befuddled, long-horned steer wearing cowboy boots. (Earlier, in the offbeat "Pandemonia" sequence, LBJ had been cast as a prairie centaur named The Loan Arranger, whose low-hung Stetson covered his eyes like a mask.) When the material from this period was collected in Equal Time for Pogo, the publisher wanted to edit out the strips featuring Robert Kennedy's doppelgänger, but Kelly insisted on keeping them in, to pay honor to the slain candidate.

In the early 1970s, Kelly used a collection of characters he called "the Bulldogs" to mock the secrecy and perceived paranoia of the Nixon administration. The Bulldogs included caricatures of J. Edgar Hoover (dressed in an overcoat and fedora, and directing a covert bureau of identical frog operatives), Spiro Agnew (portrayed as an unnamed hyena festooned in ornate military regalia), and John Mitchell (portrayed as a pipe-smoking eaglet wearing high-top sneakers.)[15] Always referred to, but never seen, was The Chief, who we are led to believe was Richard Nixon. Nixon eventually made his appearance as a reclusive, teapot-shaped spider named Sam.

The hyena character would sometimes change into Nixon for a while, then back into Agnew; at the end of the character's run, Churchy wondered, 'How many of him was there?'. The hyena was dressed in the ornate uniform when President Nixon introduced a fancy new dress uniform for the White House guards. Its appearance in the strip was marked by comments such as 'You look like a wet refugee from a third-rate road company.' and 'Stand back! It's blinding! You're the head cheese in a non-existent blintz republic, right?'. In real life, public ridicule led to the abandonment of the uniform a short time later.

J. Edgar Hoover apparently read more into the strip than was there. According to documents obtained from the Federal Bureau of Investigation under the Freedom of Information Act, Hoover had suspected Kelly of sending some form of coded messages via the nonsense poetry and Southern accents he peppered the strip with. He reportedly went so far as to have government cryptographers attempt to "decipher" the strip.[16](reference not reliable)

When the strip was revived in 1989, Doyle and Sternecky attempted to recreate this tradition with a GOP Elephant that looked like Ronald Reagan, and a jackalope resembling George H. W. Bush. Saddam Hussein was portrayed as a snake, and then Vice-President Dan Quayle was depicted as an egg, which eventually hatched into a roadrunner-type chick that made the sound "Veep! Veep!"

Backlash, censorship and "bunny strips"

Kelly's use of satire and politics often drew fire from those he was criticizing and their supporters. Due to complaints, a number of papers censored or dropped the strip altogether, while others moved it to the editorial page.

When he started a controversial storyline, Kelly usually created alternate, deliberately innocuous daily strips that papers could opt to run instead of the political ones for a given week. They are sometimes labeled "Special," or with a letter after the date, to denote that they were alternate offerings. Kelly referred to these strips as "bunny strips," because more often than not he populated the alternate strips with the least offensive material he could imagine —fluffy little bunnies telling safe, insipid jokes. Nevertheless, many of the bunny strips are subtle reworkings of the theme of the replaced strip. As if to drive home Kelly's point, some papers published both versions. Kelly told fans that if all they saw in Pogo were fluffy little bunnies, then their newspaper didn't believe they were capable of thinking for themselves, or didn't want them to. The bunny strips were usually not reproduced when Pogo strips were collected into book form. However, a few alternate strips were reprinted in Equal Time for Pogo and the 1982 collection, The Best of Pogo.

Notable quotes

"We have met the enemy and he is us."

Probably the most famous Pogo quotation is "We have met the enemy and he is us." Perhaps more than any other words written by Kelly, it perfectly sums up his attitude towards the foibles of mankind and the nature of the human condition.

The quote was a parody of a message sent in 1813 from U.S. Navy Commodore Oliver Hazard Perry to Army General William Henry Harrison after his victory in the Battle of Lake Erie, stating, "We have met the enemy, and they are ours." It first appeared in a lengthier form in "A Word to the Fore", the foreword of the book The Pogo Papers, first published in 1953. Since the strips reprinted in Papers included the first appearances of Mole and Simple J. Malarkey, beginning Kelly's attacks on McCarthyism, Kelly used the foreword to defend his actions:

Traces of nobility, gentleness and courage persist in all people, do what we will to stamp out the trend. So, too, do those characteristics which are ugly. It is just unfortunate that in the clumsy hands of a cartoonist all traits become ridiculous, leading to a certain amount of self-conscious expostulation and the desire to join battle. There is no need to sally forth, for it remains true that those things which make us human are, curiously enough, always close at hand. Resolve then, that on this very ground, with small flags waving and tinny blasts on tiny trumpets, we shall meet the enemy, and not only may he be ours, he may be us. Forward!— Walt Kelly, June 1953

The finalized version of the quotation appeared in a 1970 anti-pollution poster for Earth Day and was repeated a year later in the daily strip. The slogan also served as the title for the last Pogo collection released before Kelly's death in 1973, and of an environmentally themed animated short on which Kelly had started work, but did not finish due to ill health.

In 1998, OGPI (Okefenokee Glee & Perloo Incorporated, the corporation formed by the Kelly family to administer all things Pogo) dedicated a plaque in Waycross, Georgia, commemorating the quote.

Other quotes

Perhaps the second best-known Walt Kelly quotation is one of Porky Pine's philosophical observations: "Don't take life so serious, son. It ain't nohow permanent." Kelly's widow Selby re-used the line as a tribute, in a poignant daily strip that ran on Christmas Day, 1973 — two months after Kelly's death.

Personal references

Walt Kelly frequently had his characters poling around the swamp in a flat-bottomed skiff. Invariably, it had a name on the side that was a personal reference of Kelly's: the name of a friend, a political figure, a fellow cartoonist, or the name of a newspaper, its editor or publisher. The name changed from one day to the next, and even from panel to panel in the same strip, but it was usually a tribute to a real-life person Kelly wished to salute in print.

Awards and recognition

Long before I could grasp the satirical significance of his stuff, I was enchanted by Kelly's magnificent artwork ... We'll never see anything like Pogo again in the funnies, I'm afraid.— Jeff MacNelly, from Pogo Even Better, 1984

A good many of us used hoopla and hype to sell our wares, but Kelly didn't need that. It seemed he simply emerged, was there, and was recognized for what he was, a true natural genius of comic art ... Hell, he could draw a tree that would send God and Joyce Kilmer back to the drawing board.— Mort Walker, from Outrageously Pogo, 1985

The creator and series have received a great deal of recognition over the years. Walt Kelly has been compared to everyone from James Joyce and Lewis Carroll, to Aesop and Joel Chandler Harris (Uncle Remus).[17][18] His skills as a humorous illustrator of animals has been celebrated alongside those of John Tenniel, A. B. Frost, T. S. Sullivant, Heinrich Kley and Lawson Wood. In his essay "The Decline of the Comics" (Canadian Forum, January 1954), literary critic Hugh MacLean classified American comic strips into four types: daily gag, adventure, soap opera and "an almost lost comic ideal: the disinterested comment on life's pattern and meaning." In the fourth type, according to MacLean, there were only two: Pogo and Li'l Abner. When the first Pogo collection was published in 1951, Anthony Boucher and J. Francis McComas declared that "nothing comparable has happened in the history of the comic strip since George Herriman's Krazy Kat." [19]

"Carl Sandburg said that many comics were too sad, but, 'I Go Pogo.' Francis Taylor, Director of the Metropolitan Museum, said before the Herald Tribune Forum: 'Pogo has not yet supplanted Shakespeare or the King James Version of the Bible in our schools.' " [20] Kelly was elected president of the National Cartoonists Society in 1954, serving until 1956. He was the first strip cartoonist invited to contribute originals to the Library of Congress.

- Kelly received the National Cartoonists Society's Billy DeBeck Memorial Award for Cartoonist of the Year in 1951. (When the award name was changed in 1954, Kelly also retroactively received a Reuben statuette.)

- The prestigious Silver T-Square is awarded, by unanimous vote of the NCS Board of Directors, to persons who have demonstrated outstanding dedication or service to the Society or the profession; Kelly received one in 1972.

- The Comic-Con International Inkpot Award was given to Kelly posthumously in 1989.

- Kelly is one of only 31 artists elected to the Hall of Fame of the National Cartoon Museum (formerly the International Museum of Cartoon Art).

- Kelly was also inducted into the Will Eisner Award Hall of Fame in 1995.

- The Fantagraphics Pogo collections were a top vote-getter for the Comics Buyer's Guide Fan Award for Favorite Reprint Graphic Album for 1998.

Influence and legacy

Walt Kelly's work has influenced a number of prominent comic artists:

- From 1951 to 1954, Famous Studios animator Irv Spector drew the syndicated Coogy strip, which was heavily influenced by Kelly's work, for the New York Herald-Tribune.

- In the Calvin and Hobbes Tenth Anniversary Book, cartoonist Bill Watterson listed Pogo as one of the three greatest influences on Calvin and Hobbes, along with Peanuts and Krazy Kat.

- Pogo has been cited as an influence by Jeff MacNelly (Shoe), Garry Trudeau (Doonesbury), Bill Holbrook (Kevin and Kell ) and Mark O'Hare (Citizen Dog), among others.

- René Goscinny and Albert Uderzo were both admirers of Pogo, and many of Walt Kelly's visual devices resurfaced in Astérix. For example, the Goths speak in Olde English blackletter text, and a Roman tax-collector speaks in bureaucratic forms.

- Jim Henson acknowledged Kelly as a major influence on his sense of humor, and based some early Muppet designs on Kelly drawings. One episode of The Muppet Show's first season included a performance of "Don't Sugar Me" from Songs of the Pogo.

- Robert Crumb cites Pogo as an influence on Animal Town, an early series of comic strips he drew with his brother Charles that later formed the basis for R. Crumb's Fritz the Cat.[21]

- Harvey Kurtzman parodied Pogo as "Gopo Gossum" for the comic book Mad #23, published by EC Comics in 1955. It was the first of many Mad references to Pogo, most of them drawn by Wally Wood. According to The Best of Pogo (1982), "Walt Kelly was well aware of the Mad parodies, and loved them." Kelly directly acknowledged Wally Wood, and even had Albert spell out his name in Pogo Extra: Election Special (1960).

- Writer Alan Moore and artist Shawn McManus made the January 1985 issue (#32) of Saga of the Swamp Thing a tribute to Pogo (titled "Pog"), with Kellyesque wordplay and artwork.

- Jeff Smith acknowledged that his Bone comic book series was strongly influenced by Walt Kelly's work. Smith and Peter Kelly contributed artwork of the cast of Bone meeting Pogo and Albert for the 1998 "Pogofest" celebration.

- In the Nickelodeon animated series, "The Loud House", which draws heavy inspiration from comic strips, features a bird named after Kelly, Walt.

Last strips

According to Walt Kelly's widow Selby Kelly[22] Walt Kelly fell ill in 1972 and was unable to continue the strip. At first, reprints, mostly with minor rewording in the word balloons, from the 1950s and 1960s were used, starting Sunday, 4 June 1972. Kelly returned for just eight Sunday pages, 8 October 1972 to 26 November 1972, but according to Selby was unable to draw the characters as large as he customarily did. The reprints with minor rewording returned, and Kelly died 18 October 1973. Other artists, notably Don Morgan, worked on the strip. Selby Kelly began to draw the strip with the Christmas strip from 1973, from scripts by Walt's son Stephen. The strip ended 20 July 1975.

In 1989, the Los Angeles Times revived the strip under the title Walt Kelly's Pogo, written at first by Doyle and Sternecky, then by Sternecky alone. After Sternecky quit in March 1992, Kelly's son Peter and daughter Carolyn continued to produce the strip, but interest waned and the revived strip was dropped from syndication after only a few years.

Pogo in other media

At its peak, Walt Kelly's possum appeared in nearly 500 newspapers in 14 countries. Pogo's exploits were collected into more than four dozen books, which collectively sold close to 30 million copies. Pogo already had had a successful life in comic books, previous to syndication. The increased visibility of the newspaper strip and popular trade paperback titles allowed Kelly's characters to branch into other media, such as television, children's records, and even a theatrical film.

In addition, Walt Kelly appeared as himself on television at least twice. He was interviewed live by Edward R. Murrow for his program Person to Person, in an episode originally broadcast on 14 January 1954. Kelly can also be seen briefly in the 1970 NBC-TV special This Is Al Capp, talking candidly about his friend, the creator of Li'l Abner.

Comic books and periodicals

All comic book titles are published by Dell Publishing Company, unless otherwise noted:

- Albert the Alligator and Pogo Possum (1945–1946) Dell Four Color issues #105 and 148

- Animal Comics (1947) issues #17, 23–25

- Pogo Possum (1949–1954) issues #1–16

- "Pogo's Papa" by Murray Robinson, from Collier's Weekly (8 March 1952)

- Pogo Parade (1953), a compilation of previously published Dell Pogo stories

- Pogo Coloring Book (1953) Whitman Publishing

- "Pogo: The Funnies are Getting Funny" from Newsweek (21 June 1954) Pogo cover painting by Kelly

- "Pogo Meets a Possum" by Walt Kelly, from Collier's Weekly (29 April 1955)

- "Bright Christmas Land" from Newsweek (26 December 1955) Pogo cover painting by Kelly

- "Pogo Looks at the Abominable Snowman," from Saturday Review (30 August 1958) Pogo cover illustration by Kelly

- Pogo Primer for Parents: TV Division (1961), a public services giveaway booklet distributed by the US HEW

- Pogo Coloring Book (1964) Treasure Books (different from the 1953 book of the same name)

- Pogo: Welcome to the Beginning (1965), a public services giveaway pamphlet distributed by the Neighborhood Youth Corps

- Pogo: Bienvenidos al Comienzo (1965), Spanish-language version of the above title

- "The Pogofenokee Swamp" from Jack and Jill (May 1969)

- The Okefenokee Star (1977–1982), a privately published fanzine devoted to Walt Kelly and Pogo

- The Comics Journal #140 (Feb. 1991) Special Walt Kelly Issue

- "Al Capp and Walt Kelly: Pioneers of Political and Social Satire in the Comics" by Kalman Goldstein, from The Journal of Popular Culture; Vol. 25, Issue 4 (Spring 1992)

Music and recordings

- Songs of the Pogo (1956): A vinyl LP collecting 18 of Kelly's verses (most of which had previously appeared in Pogo books) set to music by both Kelly and orchestra leader Norman Monath. While professional singers (including Bob McGrath, later famous as "Bob" on the children's television show Sesame Street) provided most of the vocals on the album, Kelly himself contributed lead vocals on "Go Go Pogo" (for which he also composed the music) and "Lines Upon a Tranquil Brow," as well as a spoken portion for "Man's Best Friend." Mike Stewart, who was later known for singing the theme song of Bat Masterson, sang "Whence that Wince," "Evidence" and "Whither the Starling."

- A "sampler" from Songs of the Pogo was issued on vinyl 45 at the same time. The three-track record included "Go Go Pogo" and "Lines Upon a Tranquil Brow" sung by Walt Kelly, and "Don't Sugar Me" sung by Fia Karin with "orchestra and chorus under the direction of Jimmy Carroll." The recording was issued by Simon and Schuster, with only ASCAP 100A and B as recording numbers.

- The Firehouse Five Plus 2 Goes South (1956): LP, with liner notes and back album sleeve illustration by Walt Kelly. (Good Time Jazz)

- Jingle Bell Jazz, (Columbia LP CS 8693, issued October 17, 1962, reissued as Harmony KH-32529 on September 28, 1973 with one substitution; The Harmony issue was reissued as Columbia Jazz Odyssey Stereo LP PC 36803), a collection of a dozen jazz Christmas songs by different performers, includes "Deck Us All with Boston Charlie" recorded on 4 May 1961 by Lambert, Hendricks, & Ross with the Ike Isaacs Trio. The recording features a center section of Jon Hendricks scatting to the melody, with Kelly's lyrics sung as introduction and close.

- NO! with Pogo (1969): 45 rpm record for children, narrated and sung by "P. T. Bridgeport" (Kelly) with The Carillon Singers; came with a color storybook illustrated by Kelly. (Columbia Book & Record Library/Lancelot Press)

- CAN'T! with Pogo (1969): 45 rpm record for children, same credits as above.

- The Comics Journal Interview CD (2002): Contains 15-20 minute excerpts with five of the most influential cartoonists in the American comics industry: Charles Schulz, Jack Kirby, Walt Kelly (interviewed by Gil Kane in 1969) and R. Crumb. From the liner notes: "Hear these cartoonists in their own words, discussing the craft that made them famous." (Fantagraphics)

- Songs of the Pogo was released on CD in 2004 by Reaction Records (Urbana, Illinois), including previously unreleased material.

Animation and puppetry

Three animated cartoons were created to date based on Pogo:

- The Pogo Special Birthday Special [23] was produced and directed by animator Chuck Jones in honor of the strip's 20th anniversary in 1969. It starred June Foray as the voice of both Pogo and Hepzibah, with Kelly and Jones contributing voice work as well. The critical consensus is that the special, which first aired on NBC-TV on 18 May 1969, failed to capture the charm of the comic strip. Kelly wasn't pleased with the results, and it is generally dismissed by fans.[1]

- Walt and Selby Kelly themselves wrote and animated We Have Met the Enemy and He Is Us in 1970, largely due to Kelly's dissatisfaction with the Birthday Special. The short, with its anti-pollution message, was animated and colored by hand. While the project went unfinished due to Kelly's ill health, the storyboards for the cartoon helped form the first half of the book of the same title.

- The theatrical, feature-length motion picture I Go Pogo (a.k.a. Pogo for President [24] ) was released in late August 1980. Directed by Marc Paul Chinoy, this stop motion animated feature starred the voices of Skip Hinnant as Pogo; Ruth Buzzi as Miz Beaver and Hepzibah; Stan Freberg as Albert; Arnold Stang as Churchy; Jonathan Winters as Porky, Mole, and Wiley Catt; Kelly's friend, New York journalist Jimmy Breslin as P. T. Bridgeport; and Vincent Price as the Deacon. While some fans have embraced the movie, others have dismissed it (as with the Birthday Special) for lacking Kelly's wit and charm.

The Birthday Special and I Go Pogo were released on home video throughout the 1980s and 1990s. The Birthday Special was released on VHS by MGM/UA Home Video in 1986 and they alongside with Turner Entertainment released it on VHS again on August 1, 1992.

I Go Pogo was handled by Fotomat for its original VHS and Betamax release in September 1980. HBO premiered a re-cut version of the film in October 1982, with added narration by Len Maxwell; this version would continue to air on HBO for some time, and then on other cable movie stations like Cinemax, TMC, and Showtime, until around February 1991. Walt Disney Home Video released a similar cut of the film in 1984, with some deleted scenes added/restored. This version of the film was released on VHS again on December 4, 1989, by Walt Disney Home Video and United American Video to the "sell through" home video market.

As of March 17, 2016, there's still no word of Warner Bros. and Turner Entertainment planning to release Birthday Special on DVD. That special (along with I Go Pogo) have never officially been made available on DVD. Selby Kelly had been selling specially packaged DVDs of We Have Met the Enemy and He Is Us prior to her death, but it is unknown whether or not further copies will be available.

Licensing and promotion

Pogo also branched out from the comic pages into consumer products — including TV sponsor tie-ins to the Birthday Special — although not nearly to the degree of other contemporary comic strips, such as Peanuts. Selby Kelly has attributed the comparative paucity of licensed material to Kelly's pickiness about the quality of merchandise attached to his characters.

- 1951: Special Delivery Pogo, a 16-page promotional mailer from the Post-Hall Syndicate, designed to spark interest and boost circulation of the new strip.

- 1952: "I Go Pogo" tin litho lapel pinback. Approx. 1 inch in diameter, with Pogo's face on a yellow background; issued as a promotional giveaway during the 1952 presidential election.

- 1954: Walt Kelly's Pogo Mobile (issued by Simon and Schuster) was a 22-piece hanging mobile, die-cut from heavy cardboard in bright colors. Came unassembled, and included Pogo on a cow jumping over a crescent-shaped Swiss cheese moon, with Okefenokee characters sitting on the moon or in a filigreed frame.

- 1959: Rare porcelain figurine of a sitting Pogo, with a bird in a nest atop his head; made in Ireland by Wade Ceramics Ltd.

- 1968: Set of 30 celluloid pinback buttons, quite rare. Approx. 1.75 inches in diameter, issued during the 1968 presidential elections.

- 1968: Set of 10 color character decals, very rare; coincided with the set of election pinbacks

- 1968: Poynter Products of Ohio issued a set of six plastic figures (now very rare) with glued-on artificial fur: Pogo, Albert, Beauregard, Churchy, Howland and Hepzibah. The figures displeased Kelly, but are highly sought-after by fans.

- 1969: Six vinyl giveaway figures of Pogo, Albert, Beauregard, Churchy, Howland and Porkypine, packaged with Procter & Gamble soap products (Spic and Span, Top Job, etc.) as a tie-in with the Pogo animated TV special. Also known as the Oxydol figures, they are fairly common and easy to find. Walt Kelly was not satisfied with the initial sculpting, and — using plasticine clay — resculpted them himself.[25]

- 1969: Six plastic giveaway cups with full-color character decals of Pogo, Albert, Beauregard, Churchy, Howland and Porkypine, coincided with the Oxydol figures.

- 1969: Pogo Halloween costume, manufactured by Ben Cooper.

- 1980: View-Master I Go Pogo set, 3 reels & booklet, GAF

- 2002: Dark Horse Comics issued two limited edition figures of Pogo and Albert as part of their line of Classic Comic Characters — statues #24 and #25, respectively.

Collections and reprints

The 45 Pogo books published by Simon & Schuster

All titles are by Walt Kelly:

- Pogo (1951)

- I Go Pogo (1952)

- Uncle Pogo So-So Stories (1953)

- The Pogo Papers (1953)

- The Pogo Stepmother Goose (1954)

- The Incompleat Pogo (1954)

- The Pogo Peek-A-Book (1955)

- Potluck Pogo (1955)

- The Pogo Sunday Book (1956)

- The Pogo Party (1956)

- Songs of the Pogo (1956)

- Pogo's Sunday Punch (1957)

- Positively Pogo (1957)

- The Pogo Sunday Parade (1958)

- G.O. Fizzickle Pogo (1958)

- Ten Ever-Lovin', Blue-Eyed Years with Pogo (1959)

- The Pogo Sunday Brunch (1959)

- Pogo Extra (Election Special) (1960)

- Beau Pogo (1960)

- Gone Pogo (1961)

- Pogo à la Sundae (1961)

- Instant Pogo (1962)

- The Jack Acid Society Black Book (1962)

- Pogo Puce Stamp Catalog (1963)

- Deck Us All with Boston Charlie (1963)

- The Return of Pogo (1965)

- The Pogo Poop Book (1966)

- Prehysterical Pogo (in Pandemonia) (1967)

- Equal Time for Pogo (1968)

- Pogo: Prisoner of Love (1969)

- Impollutable Pogo (1970)

- Pogo: We Have Met the Enemy and He Is Us (1972)

- Pogo Revisited (1974), a compilation of Instant Pogo, The Jack Acid Society Black Book and The Pogo Poop Book

- Pogo Re-Runs (1974), a compilation of I Go Pogo, The Pogo Party and Pogo Extra (Election Special)

- Pogo Romances Recaptured (1975), a compilation of Pogo: Prisoner of Love and The Incompleat Pogo

- Pogo's Bats and the Belles Free (1976)

- Pogo's Body Politic (1976)

- A Pogo Panorama (1977), a compilation of The Pogo Stepmother Goose, The Pogo Peek-A-Book and Uncle Pogo So-So Stories

- Pogo's Double Sundae (1978), a compilation of The Pogo Sunday Parade and The Pogo Sunday Brunch

- Pogo's Will Be That Was (1979), a compilation of G.O. Fizzickle Pogo and Positively Pogo

- The Best of Pogo (1982)

- Pogo Even Better (1984)

- Outrageously Pogo (1985)

- Pluperfect Pogo (1987)

- Phi Beta Pogo (1989)

Pogo books released by other publishers

All titles are by Walt Kelly unless otherwise noted:

- Pogo for President: Selections from I Go Pogo (Crest Books, 1964)

- The Pogo Candidature by Walt Kelly and Selby Kelly (Sheed, Andrews & McMeel, 1976)

- Ten S&S volumes were reprinted in hardcover (Gregg Press, 1977): Pogo, I Go Pogo, Uncle Pogo So-So Stories, The Pogo Papers, The Pogo Stepmother Goose, The Incompleat Pogo, The Pogo Peek-A-Book, Potluck Pogo, Gone Pogo, and Pogo à la Sundae. Bound in brown cloth, with the individual titles and an "I Go Pogo" logo stamped in gold. The dust jackets are facsimiles of the original Simon & Schuster covers, with an image of Walt Kelly reproduced on the back.

- The Walt Kelly Collector's Guide by Steve Thompson (Spring Hollow Books, 1988)

- The Complete Pogo Comics: Pogo & Albert (Eclipse Comics, 1989–1990) 4 volumes (reprints of pre-strip comic book stories, unfinished)

- Pogo Files for Pogophiles, Selby Daly Kelly and Steve Thompson, eds. (Spring Hollow Books, 1992)

- Ten more S&S volumes reprinted in hardcover (Jonas/Winter Inc., 1995): The Pogo Sunday Book, Pogo's Sunday Punch, Beau Pogo, Pogo Puce Stamp Catalog, Deck Us All with Boston Charlie, The Return of Pogo, Prehysterical Pogo (in Pandemonia), Equal Time for Pogo, Impollutable Pogo, and Pogo: We Have Met the Enemy and He Is Us. Bound in navy blue cloth, with the individual titles and a "Pogo Collectors Edition" logo stamped in gold. Issued without dust jackets.

- Pogo (Fantagraphics Books, 1994–2000) 11 volumes (reprints first 5½ years of daily strips)

- The Pogopedia by Nik Lauer, et al. (Spring Hollow Books, 2001) ISBN 0-945185-05-7

- Walt Kelly's Pogo: The Complete Dell Comics (Hermes Press, 2013–2015) 3 volumes (reprints of pre-strip comic book stories)

The Complete Pogo

In February 2007, Fantagraphics Books announced the publication of a projected 12-volume hardcover series collecting the complete chronological run of daily and full-color Sunday syndicated Pogo strips. The first volume was originally scheduled to appear in October 2007, but difficulties in obtaining and restoring early source material delayed its publication until November 2011.[26][27][28]

- Pogo: Through the Wild Blue Wonder: The Complete Syndicated Comic Strips, Vol. 1: 1949–1950 (Fantagraphics, November 2011) ISBN 1-56097-869-4

- Pogo: Bona Fide Balderdash: The Complete Syndicated Comic Strips, Vol. 2: 1951–1952 (Fantagraphics, November 2012) ISBN 1-60699-584-7

- Pogo: Evidence to the Contrary: The Complete Syndicated Comic Strips, Vol. 3: 1953–1954 (Fantagraphics, November 2014) ISBN 1-60699-694-0

- Pogo: Under the Bamboozle Bush: The Complete Syndicated Comic Strips, Vol. 4: 1955–1956 (Fantagraphics, December 2016) ISBN 1-60699-863-3

Notes

- 1 2 Don Markstein's Toonopedia. "Pogo Possum".

- ↑ Kelly, Walt: Phi Beta Pogo, p. 206, Simon and Schuster, 1989.

- ↑ See, for example, Positively Pogo (Simon & Schuster, 1957) p. 85; also Gone Pogo (Simon & Schuster, 1961) p. 57; also Instant Pogo (Simon & Schuster, 1962) p. 40.

- ↑ "Television Is Discovered in the Okefenokee Swamp, and Vice Versa," from TV Guide, 17 May 1969.

- ↑ The Straight Dope: Complete Lyrics to "Deck Us All with Boston Charlie"

- ↑ Kelly, Walt: Ten Ever-Lovin', Blue-Eyed Years with Pogo, p. 284, Simon and Schuster, 1959.

- ↑ Soper, Kerry D. (2012). We Go Pogo: Walt Kelly, Politics and American Satire. Jackson, Miss.: University Press of Mississippi. p. 96. ISBN 1-61703-284-0.

- ↑ Georgia State 'Possum

- ↑ Excerpted from a 1949 strip reproduced in the collection Pogo, Post-Hall Syndicate, 1951.

- ↑ "Big Deals: Comics’ Highest-Profile Moments," Hogan's Alley #7, 1999

- ↑ Kelly, Walt: Ten Ever-Lovin', Blue-Eyed Years with Pogo, p. 81, Simon and Schuster, 1959.

- ↑ Kelly, Walt: Ten Ever-Lovin', Blue-Eyed Years with Pogo, p. 141, Simon and Schuster, 1959.

- ↑ Kelly, Walt: Ten Ever-Lovin', Blue-Eyed Years with Pogo, p. 152, Simon and Schuster, 1959.

- ↑ The poetry collection Deck Us All with Boston Charlie also lacks "Pogo" in its title, but is not a collection of strips.

- ↑ "The Comics on the Couch" by Gerald Clarke, Time Dec. 13, 1971

- ↑ For Sprint Hath Sprung the Cyclotron by Cyrus Highsmith, 20 March 2009

- ↑ Crowley, John, "The Happy Place: Walt Kelly's Pogo", [[Boston Review Oct./Nov. 2004 Archives]

- ↑ Willson, John, "American Aesop," The Imaginative Conservative 18 July 2010

- ↑ "Recommended Reading," The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, April 1952, p.96.

- ↑ From an autobiography written by Walt Kelly for the Hall Syndicate, 1954

- ↑ Crumb, Robert (February 1978). "Introduction". The Complete Fritz the Cat. Belier Press. ISBN 978-0-914646-16-7.

- ↑ Selby Daley Kelly & Steve Thompson, Pogo Files for Pogophiles, Spring Hollow Books, 1992, ISBN 0945185030

- ↑ The Pogo Special Birthday Special at the Internet Movie Database

- ↑ http://cartoonresearch.com/index.php/animated-movie-guide-1/

- ↑ Kelly, Walt: "Phi Beta Pogo", p. 212, Simon and Schuster, 1989.

- ↑ "Fantagraphics announces the complete POGO!". Flog! The Fantagraphics Blog. 2007-02-15. Archived from the original on 2007-09-27. Retrieved 2007-11-29.

- ↑ "New volumes of Pogo reprints delayed". Comic Book Bin. 2008-07-31. Retrieved 2008-09-14.

- ↑ Kim Thompson (2009-03-20). "Will The Complete Pogo happen in 2009?". The Comics Journal Message Board. Retrieved 2009-12-09.

POGO has production difficulties due to the really horrible state of the first year's worth of Sundays in all available versions. We're taking our time on it because we want to do it right. It will definitely NOT be out in 2009.

Further reading

- The Complete Nursery Song Book, Inez Bertail, ed. (Lothrop, Lee & Shepard, 1947) illustrated by Walt Kelly

- Strong Cigars and Lovely Women by John Lardner (Funk & Wagnalls, 1951) illustrated by Walt Kelly

- The Pleasure Was All Mine by Fred Schwed, Jr. (Simon & Schuster, 1951) illustrated by Walt Kelly

- The Glob by John O'Reilly (Viking, 1952) illustrated by Walt Kelly

- The Tattooed Sailor and Other Cartoons from France by Andre Francois (Knopf, 1953) Introduction by Walt Kelly

- I'd Rather Be President by John Ellis and Frank Weir (Simon & Schuster, 1956) illustrated by Walt Kelly

- The World of John Lardner, Roger Kahn, ed. (Simon & Schuster, 1961) Preface by Walt Kelly

- Dear George by John Keasler (Simon & Schuster, 1962) illustrated by Walt Kelly

- Five Boyhoods, Martin Levin, ed. (Doubleday, 1962) Walt Kelly autobiography, pp. 79–116

- The Funnies: An American Idiom, David Manning White and Robert H. Abel, eds. (Free Press, 1963)

- Art Afterpieces by Ward Kimball (Pocket Books, 1964) Forward by Walt Kelly

- The Comics: An Illustrated History of Comic Strip Art by Jerry Robinson (G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1974)

- The World Encyclopedia of Comics by Maurice Horn (Chelsea House, 1976; Avon, 1982)

- The Smithsonian Collection of Newspaper Comics, Bill Blackbeard, ed. (Smithsonian Inst. Press/Harry Abrams, 1977)

- A Smithsonian Book of Comic-Book Comics, Michael Barrier and Martin Williams, eds. (Smithsonian Inst. Press/Harry Abrams, 1982)

- America's Great Comic Strip Artists by Rick Marschall (Abbeville Press, 1989)

- Walt Kelly's Our Gang (Fantagraphics, 2006–2010) 4 volumes

- Comics and the U.S. South, Brannon Costello and Qiana J. Whitted, eds., pp. 29–56 (Univ. Press of Mississippi, 2012) ISBN 1-617030-18-X

- We Go Pogo: Walt Kelly, Politics and American Satire by Kerry D. Soper (Univ. Press of Mississippi, 2012) ISBN 1-61703-284-0

- The Life and Times of Walt Kelly by Thomas Andrae and Carsten Laqua (Hermes Press, 2012) ISBN 1-932563-89-X

External links

- Ever-Lovin' Blue-Eyed Whirled of Kelly

- Okefenokee Swamp Park - Pogo and the Walt Kelly Museum

- Pogo Fan Club & Walt Kelly Society

- Samples, artist and writer data on the 1989-93 revival of the comic strip

- The Ohio State University Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum: Pogo Collection guide