Minh Mạng

| Minh Mạng | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emperor of Đại Nam | |||||||||||||||||

Portrait of Emperor Minh Mang | |||||||||||||||||

| Reign | 14 February 1820 – 20 January 1841 | ||||||||||||||||

| Predecessor | Gia Long | ||||||||||||||||

| Successor | Thiệu Trị | ||||||||||||||||

| Born |

25 May 1791 Gia Định, Đại Nam | ||||||||||||||||

| Died |

20 January 1841 (aged 49) Phú Xuân, Đại Nam | ||||||||||||||||

| Burial | Hiếu Lăng | ||||||||||||||||

| Spouse | Empress Tá Thiên | ||||||||||||||||

| Issue |

Nguyễn Phúc Miên Tông, Emperor Thiệu Trị 77 other sons and 64 daughters | ||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| House | Nguyễn dynasty | ||||||||||||||||

| Father | Emperor Gia Long | ||||||||||||||||

| Mother | Empress Thuận Thiên | ||||||||||||||||

| Religion | Confucianism | ||||||||||||||||

| Signature |

| ||||||||||||||||

Minh Mạng (25 May 1791 – 20 January 1841; born Nguyễn Phúc Đảm, also known as Nguyễn Phúc Kiểu) was the second emperor of the Nguyễn dynasty of Vietnam, reigning from 14 February 1820 until his death, on 20 January 1841.[1] He was the fourth son of Emperor Gia Long, whose eldest son, Crown Prince Cảnh, had died in 1801. He was well known for his opposition to French involvement in Vietnam and his rigid Confucian orthodoxy.

Early years

| Minh Mạng | |

| Vietnamese name | |

|---|---|

| Vietnamese | Minh Mạng |

| Hán-Nôm | 明命 |

| Birth name | |

| Vietnamese alphabet | Nguyễn Phúc Đảm |

|---|---|

| Hán-Nôm | 阮福膽 |

Born Nguyễn Phúc Đảm at Gia Định in the middle of the Second Tây Sơn - Nguyễn Civil War, Minh Mạng was the fourth son of lord Nguyễn Phúc Ánh - future Emperor Gia Long. His mother was Gia Long’s second wife Trần Thị Đang (historically known as Empress Thuận Thiên). At the age of three, under the effect of a written agreement made by Gia Long with his first wife Tống Thị Lan (Empress Thừa Thiên), he was taken in and raised by the lord consort as her own son.[2]

Following Thừa Thiên’s death in 1814, it was supposed that her grandson, Crown Prince Cảnh’s eldest son Mỹ Đường, would be responsible for conducting the funeral. Gia Long however, brought out the agreement to insist that Phúc Đảm, as Thừa Thiên’s son, should be the one fulfilling the duty. Despite opposition from mandarins such as Nguyễn Văn Thành, Gia Long was decisive with his selection.[3]

In 1816, Gia Long appointed Đảm as his heir apparent. After the ceremony, Crown Prince Đảm moved to Thanh Hòa Palace and started assisting his father in processing documents and discussing country issues.[4]

Gia Long's death coincided with the re-establishment of the Paris Missionary Society's operations in Vietnam, which had closed in 1792 during the chaos of the power struggle between Gia Long and the Tây Sơn brothers before Vietnam was unified. In the early years of Minh Mạng's government, the most serious challenge came from one of his father's most trusted lieutenants and a national hero in Vietnam, Lê Văn Duyệt, who had led the Nguyễn forces to victory at Qui Nhơn in 1801 against the Tây Sơn Dynasty and was made regent in the south by Gia Long with full freedom to rule and deal with foreign powers.

Policy towards missionaries

In February 1825, Minh Mạng banned missionaries from entering Vietnam. French vessels entering Vietnamese harbours were ordered to be searched with extra care. All entries were to be watched "lest some masters of the European religion enter furtively, mix with the people and spread darkness in the kingdom." In an imperial edict, Christianity was described as the "perverse European" (practice) and accused of "corrupting the hearts of men".[5]

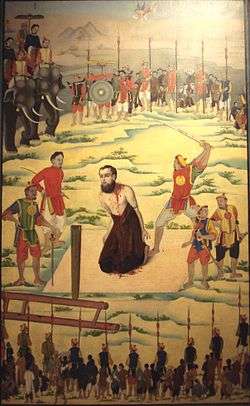

Between 1833 and 1838, seven missionaries were sentenced to death. He first attempted to stifle the spread of Christianity by attempting to isolate Catholic priests and missionaries from the populace. He asserted that he had no French interpreters after Chaigneau's departure and summoned the French clergy to Hue and appointed them as mandarins of high rank to woo them from their proselytising. This worked until a priest, Father Regereau, entered the country and began missionary work. Following the edict which forbade further entry of missionaries into Vietnam, arrests of clerics began. After strong lobbying by Duyệt, the governor of Cochin China, and a close confidant of Gia Long and Pigneau de Behaine, Minh Mạng agreed to release the priests on the condition that they congregate at Đà Nẵng and return to France. Some of them obeyed the orders, but others disobeyed the order upon being released, and returned to their parishes and resumed preaching.

Isolationist foreign policy

Minh Mạng continued and intensified his father's isolationist and conservative Confucian policies. His father had rebuffed a British delegation in 1804 proposing that Vietnam be opened to trade. The delegation's gifts were not accepted and turned away. At the time, Vietnam was under no threat of colonisation, since most of Europe was engaged in the Napoleonic Wars. Nevertheless, Napoleon had seen Vietnam as a strategically important objective in the colonial power struggle in Asia, as he felt that it would make an ideal base from which to contest the British East India Company's control of the Indian subcontinent. With the restoration of the monarchy and the final departure of Napoleon in 1815, the military scene in Europe quieted and French interest in Vietnam was revived. Jean-Baptiste Chaigneau, one of the volunteers of Pigneau de Behaine who had helped Gia Long in his quest for power, had become a mandarin and continued to serve Minh Mạng, upon whose ascension, Chaigneau and his colleagues were treated more distantly. He eventually left in November 1824. In 1825, he was appointed as French consul to Vietnam after returning to his homeland to visit his family after more than a quarter of a century in Asia. Upon his return, Minh Mạng received him coldly. The policy of isolationism soon saw Vietnam fall further behind and become more vulnerable as political stability returned to continental Europe, allowing her colonial powers a free hand to once again direct their attention towards further conquests. With his Confucian orthodoxy, Minh Mạng shunned all western influence and ideas as hostile and avoided all contact.

In 1820, Captain John White of the United States Navy was the first American to make contact with Vietnam, arriving in Saigon. Minh Mạng was willing to sign a contract, but only to purchase artillery, firearms, uniforms and books. White was of the opinion that the deal was not sufficiently advantageous and nothing was implemented. In 1821, a trade agreement from Louis XVIII was turned away, with Minh Mạng indicating that no special deal would be offered to any country. That same year, British East India Company agent John Crawfurd made another English attempt at contact, but was only allowed to disembark in the northern ports of Tonkin; he gained no agreements, but concluded relations with France posed no threat to Company trade.[6] In 1822, the French frigate La Cleopatre visited Tourane (present day Đà Nẵng). Her captain was to pay his respects to Minh Mạng, but was greeted with a symbolic dispatch of troops as though an invasion had been expected. In 1824 Minh rejected the offer of an alliance from Burma against Siam, a common enemy of both countries. In 1824 Henri Baron de Bougainville was sent by Louis XVIII to Vietnam with the stated mission "of peace and protection of commerce. Upon arriving in Tourane in 1825, it was not allowed ashore. The royal message was turned away on the pretext that there was nobody able to translate it. It was assumed that the snub was related to an attempt by Bougainville to smuggle ashore a Catholic missionary from the Missions étrangères de Paris. Jean-Baptiste Chaigneau's nephew, Eugène Chaigneau, was sent to Vietnam in 1826 as the intended consul but was forced to leave the country without taking up his position. Further fruitless attempts to start a commercial deal were led by de Kergariou in 1827 and Admiral Laplace in 1831. Another effort by Chaigneau in 1829 also failed. In 1831 another French envoy was turned away. Vietnam under Minh Mạng was the first East Asian country with whom the United States sought foreign relations. President Andrew Jackson tried twice to contact Minh Mạng, sending diplomatist Edmund Roberts in 1832, and Consul Joseph Balestier in 1836, to no avail. In 1837 and 1838, La bonite and L'Artémise were ordered to land in Tourane to attempt to gauge the situation in Vietnam with respect to missionary work. Both were met with hostility and communication was prevented. Later, in 1833 and 1834, a war with Siam was fought over control of Cambodia which for the preceding century had been reduced to impotence and fell under control of its two neighbours. After Vietnam under Gia Long gained control over Cambodia in the early 19th century, a Vietnamese-approved monarch was installed. Minh Mạng was forced to put down a Siamese attempt to regain control of the vassal as well as an invasion of southern Vietnam which coincided with rebellion by Lê Văn Khôi. The Siamese planned the invasion to coincide with the rebellion, putting enormous strain on the Nguyễn armies. Eventually, Minh Mạng's forces were able to quell the invasion as well as the revolt in Saigon, and he reacted to western aggression by blaming Christianity and showing hostility, giving the European powers to assert that intervention was needed to protect their missionaries. This resulted in missed opportunities to avert future colonisation through having friendly relations, since strong opposition was occurring in France against an invasion, wary of the costs of such a venture. After China was attacked by Britain in the Opium War, Minh Mạng attempted to build an alliance with European powers by sending a delegation of two lower rank mandarins and two interpreters in 1840. They were received in Paris by Prime Minister Marshal Soult and the Commerce Minister, but they were shunned by King Louis-Philippe. This came after the Society of Foreign Missions and the Holy See had urged a rebuke for an "enemy of the religion". The delegation went on to London, with no success.

Domestic program

On the domestic front, Minh Mạng continued his father's national policies of reorganising the administrative structure of the government. These included the construction of highways, a postal service, public storehouses for food, monetary and agrarian reforms. He continued to redistribute land periodically and forbade all other sales of land to prevent wealthy citizens from reacquiring excessive amounts of land with their money. In 1840 it was decreed that rich landowners had to return a third of their holdings to the community. Calls for basic industrialisation and diversification of the economy into fields such as mining and forestry were ignored. He further centralised the administration, introduced the definition of three levels of performance in the triennial examinations for recruiting mandarins. In 1839, Minh Mạng introduced a program of salaries and pensions for princes and mandarins to replace the traditional assignment of fief estates.

Conquests and ethnic minority policy

Minh Mang enacted the final conquest of the Champa Kingdom after the centuries long Cham–Vietnamese wars. The Cham Muslim leader Katip Suma was educated in Kelantan and came back to Champa to declare a Jihad against the Vietnamese after Emperor Minh Mang's annexation of Champa.[7][8][9][10] The Vietnamese coercively fed lizard and pig meat to Cham Muslims and cow meat to Cham Hindus against their will to punish them and assimilate them to Vietnamese culture.[11]

Minh Mang sinicized ethnic minorities such as Cambodians, claimed the legacy of Confucianism and China's Han dynasty for Vietnam, and used the term Han people 漢人 (Hán nhân) to refer to the Vietnamese.[12] Minh Mang declared that "We must hope that their barbarian habits will be subconsciously dissipated, and that they will daily become more infected by Han [Sino-Vietnamese] customs."[13] This policies were directed at the Khmer and hill tribes.[14] The Nguyen lord Nguyen Phuc Chu had referred to Vietnamese as "Han people" in 1712 when differentiating between Vietnamese and Chams.[15] It was said "Hán di hữu hạn" 漢夷有限 ("the Vietnamese and the barbarians must have clear borders" by the Gia Long Emperor (Nguyễn Phúc Ánh) when differentiating between Khmer and Vietnamese.[16] Minh Mang implemented an acculturation integration policy directed at minority non-Vietnamese peoples.[17] Thanh nhân 清人 or Đường nhân 唐人 were used to refer to ethnic Chinese by the Vietnamese while Vietnamese called themselves as Hán dân 漢民 and Hán nhân 漢人 in Vietnam during the 1800s under Nguyễn rule.[18]

"Trung Quốc" 中國 was used as a name for Vietnam by Emperor Gia Long in 1805.[19]

Chinese style clothing was forced on Vietnamese people by the Nguyễn.[20][21][22][23][24][25] Trousers have been adopted by White H'mong.[26] The trousers replaced the traditional skirts of the females of the White Hmong.[27] The tunics and trouser clothing of the Han Chinese on the Ming tradition was worn by the Vietnamese. The Ao Dai was created when tucks which were close fitting and compact were added in the 1920s to this Chinese style.[28] Trousers and tunics on the Chinese pattern in 1774 were ordered by the Vo Vuong Emperor to replace the sarong type Vietnamese clothing.[29] The Chinese clothing in the form of trousers and tunic were mandated by the Vietnamese Nguyen government. It was up to the 1920s in Vietnam's north area in isolated hamlets where skirts were worn.[30] The Chinese Ming dynasty, Tang dynasty, and Han dynasty clothing was ordered to be adopted by Vietnamese military and bureaucrats by the Nguyen Lord Nguyễn Phúc Khoát (Nguyen The Tong).[31]

Rebellions

Minh Mạng was regarded as being in touch with the concerns of the populace. Frequent local rebellions reminded him of their plight. Descendants of the old Lê dynasty fomented dissent in the north, appealing not only to the peasantry but to the Catholic minority. They attempted to enlist foreign help by promising to open up to missionaries. Local leaders in the south were upset with the loss of the relative political autonomy they enjoyed under Duyệt. With Duyệt's death in 1832, a strong defender of Christianity passed. Catholics had traditionally been inclined to side with rebel movements against the monarchy more than most Vietnamese and this erupted after Duyệt's death. Minh Mạng ordered Duyệt posthumously indicted and one hundred lashes were applied to his grave. This caused indignation against southerners who respected Duyệt. In July 1833, a revolt broke out under the leadership of his adopted son, Lê Văn Khôi. Historical opinion is divided with scholars contesting whether the grave desecration or the loss of southern autonomy after Duyệt's death was the main catalyst. Khôi's rebels brought Cochinchina under their control and proposed to replace Minh Mạng with a son of Prince Cảnh. Khôi took into hostage French missionary Joseph Marchand[32] within the citadel, thinking that his presence would win over Catholic support. Khôi enlisted Siamese support, which was forthcoming and helped put Minh Mạng on the defense for a period.

Eventually, however, the Siamese were defeated and the south was recaptured by royalist forces, who besieged Saigon. Khôi died during the siege in December 1834 and Saigon fell nine months later in September 1835 and the rebel commanders put to death. In all the estimates of the captured rebels was put between 500 and 2000, who were executed. The missionaries were rounded up and ordered out of the country. The first French missionary executed was Gagelin in October 1833, the second was Marchand, who was put to death along with the other leaders of the Saigon citadel which surrendered in September 1835. From then until 1838 five more missionaries were put to death. The missionaries began seeking protection from their home countries and the use of force against Asians.

Minh Mạng pursued a policy of cultural assimilation of non-Viet ethnic groups which from 1841, through 1845, led to southern Vietnam experiencing a series of ethnic revolts.[33]

Ruling style

Minh Mạng was known for his firmness of character, which guided his instincts in his policy making. This accentuated his unwillingness to break with orthodoxy in dealing with Vietnam's problems. His biographer, Marcel Gaultier, asserted that Minh Mạng had expressed his opinions about national policy before Gia Long's death, proposing a policy of greater isolationism and shunning westerners, and that Long tacitly approved of this. Minh Mạng was regarded as more nuanced and gentle than his father, with less forced labour and an increased perceptiveness towards the sentiment of the peasantry. His strict belief in Confucian society enabled him to neutralize rebellions incited by Christian missionaries and their Vietnamese converts. This affirmation of Vietnam's cultural and religious sovereignty angered France, which had territorial designs on Vietnam. France then furthered its policy of undermining Vietnam and, in 1858, after Minh Mang's death, French troops would briefly occupy Tourane, demanding that the so-called "persecutions" stop. This was the beginning of the French campaign to occupy and colonize Vietnam.

Although he disagreed with European culture and thinking, he studied it closely and was known for his scholarly nature. Ming Mạng was keen in Western technologies, namely mechanics, weaponry and navigation which he attempted to introduce into Vietnam. Upon hearing of the vaccination against smallpox, he organised for a French surgeon to live in a palatial residence and vaccinate the royal family against the disease. He was learned in Eastern philosophy and was regarded as an intellectually oriented monarch. He was also known for his writings as a poet. He was known for his attention to detail and micromanagement of state affairs, to a level that "astonished his contemporaries". As a result, he was held in high-regard for his devotion to running the country. When Minh Mạng died, he left the throne to his son, Emperor Thiệu Trị, who was more rigidly Confucianist and anti-imperialist than his father. During Thiệu Trị's reign, diplomatic standoffs precipitated by aspiring European imperial powers on the pretext of the "treatment" of Catholic priests gave them an excuse to use gunboat diplomacy on Vietnam, and led to increasing raids and the eventual colonisation of Vietnam by France. Nevertheless, during his reign Minh Mạng had established a more efficient government, stopped a Siamese invasion and built many national monuments in the imperial city of Huế.

Imperial succession poem

| Vietnamese Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

Minh Mạng had many wives and children, he decided to name his descendants (Nguyễn Phước or Nguyễn Phúc: all members of the Nguyễn Dynasty) by choosing the Generation name following the words of the Imperial succession poem to avoid confusion. For boys, the following poem is shown in Chữ Quốc Ngữ (modern Vietnamese script) and in chữ nôm:

|

|

Note: Hường = Hồng // Thoại = Thụy

They replaced Hồng with Hường and Thụy with Thoại because they're the forbidden names of the passed emperors or fathers.

The meaning of each name is roughly given as follows:[34]

| Name | Meaning |

|---|---|

| Miên | respecting above all the rules of life, such as meeting and parting, life and death (Trường cửu, phước duyên trên hết) |

| Hường (Hồng) | building a harmonious family (Oai hùng, đúc kết thế gia) |

| Ưng | establishing a prosperous country (Nên danh, xây dựng sơn hà) |

| Bửu | being helpful and caring toward the common people (Bối báu, lợi tha quần chúng) |

| Vĩnh | having a good reputation (Bền chí, hùng ca anh tụng) |

| Bảo | being courageous (Ôm lòng, khí dũng bình sanh) |

| Quý | being elegant (Cao sang, vinh hạnh công thành) |

| Định | being decisive (Tiền quyết, thi hành oanh liệt) |

| Long | having a typically royal appearance (Vương tướng, rồng tiên nối nghiệp) |

| Trường | being long-lasting (Vĩnh cửu, nối tiếp giống nòi) |

| Hiền | being humane (Tài đức, phúc ấm sáng soi) |

| Năng | being talented (Gương nơi khuôn phép bờ cõi) |

| Kham | being hard-working and versatile (Đảm đương, mọi cơ cấu giỏi) |

| Kế | being well-organized (Hoạch sách, mây khói cân phân) |

| Thuật | being truthful in speech (Biên chép, lời đúng ý dân) |

| Thế | being faithful to the family (Mãi thọ, cận thân gia tộc) |

| Thoại (Thụy) | being wealthy (Ngọc quý, tha hồ phước tộc) |

| Quốc | being admired by the citizens (Dân phục, nằm gốc giang san) |

| Gia | being well-established (Muôn nhà, Nguyễn vẫn huy hoàng) |

| Xương | bringing prosperity to the world (Phồn thịnh, bình an thiên hạ) |

Girls receive also a different name on each generation, for example: Công-Chúa, Công-Nữ, Công Tôn-Nữ, Công-Tằng Tôn-Nữ, Công-Huyền Tôn-Nữ, Lai-Huyền Tôn-Nữ, or shorten to Tôn-Nữ for all generations afterward.

References

- ↑ Choi Byung Wook Southern Vietnam under the reign of Minh Mạng (1820-1841) 2004

- ↑ (Vietnamese) Quốc sử quán triều Nguyễn (Nguyễn dynasty National History Office) (1997). Đại Nam liệt truyện. Volume I. Thuận Hóa Publishing House.

- ↑ (Vietnamese) Quốc sử quán triều Nguyễn (Nguyễn dynasty National History Office) (2007). Đại Nam thực lục. Volume I. Publishing House of Education. p. 801.

- ↑ (Vietnamese) Quốc sử quán triều Nguyễn (2007). Đại Nam thực lục. Publishing House of Education.

- ↑ Phan Châu Trinh and His Political Writings Chu Trinh Phan, Sính Vĩnh - 2009 - Page 3 "Deeply embedded in the East Asian traditional way of thinking, Emperor Minh Mạng saw the West as "barbarian," and thus from his perspective the most effective response was to exclude the West and repress Christianity."

- ↑ Crawfurd, John (21 August 2006) [First published 1830]. Journal of an Embassy from the Governor-general of India to the Courts of Siam and Cochin China. Volume 1 (2nd ed.). London: H. Colburn and R. Bentley. pp. 473–4. OCLC 03452414. Archived from the original on 10 October 2007. Retrieved 2 February 2012.

- ↑ Jean-François Hubert (8 May 2012). The Art of Champa. Parkstone International. pp. 25–. ISBN 978-1-78042-964-9.

- ↑ "The Raja Praong Ritual: A Memory of the Sea in Cham- Malay Relations". Cham Unesco. Archived from the original on February 6, 2015. Retrieved 25 June 2015.

- ↑ (Extracted from Truong Van Mon, “The Raja Praong Ritual: a Memory of the sea in Cham- Malay Relations”, in Memory And Knowledge Of The Sea In South Asia, Institute of Ocean and Earth Sciences, University of Malaya, Monograph Series 3, pp, 97-111. International Seminar on Martime Culture and Geopolitics & Workshop on Bajau Laut Music and Dance”, Institute of Ocean and Earth Sciences and the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, University of Malaya, 23-24/2008)

- ↑ Dharma, Po. "The Uprisings of Katip Sumat and Ja Thak Wa (1833-1835)". Cham Today. Retrieved 25 June 2015.

- ↑ Choi Byung Wook (2004). Southern Vietnam Under the Reign of Minh Mạng (1820-1841): Central Policies and Local Response. SEAP Publications. pp. 141–. ISBN 978-0-87727-138-3.

- ↑ Norman G. Owen (2005). The Emergence Of Modern Southeast Asia: A New History. University of Hawaii Press. pp. 115–. ISBN 978-0-8248-2890-5.

- ↑ A. Dirk Moses (1 January 2008). Empire, Colony, Genocide: Conquest, Occupation, and Subaltern Resistance in World History. Berghahn Books. pp. 209–. ISBN 978-1-84545-452-4. Archived from the original on 2008.

- ↑ Randall Peerenboom; Carole J. Petersen; Albert H.Y. Chen (27 September 2006). Human Rights in Asia: A Comparative Legal Study of Twelve Asian Jurisdictions, France and the USA. Routledge. pp. 474–. ISBN 978-1-134-23881-1.

- ↑ https://web.archive.org/web/20040617071243/http://kyotoreview.cseas.kyoto-u.ac.jp/issue/issue4/article_353.html

- ↑ Choi Byung Wook (2004). Southern Vietnam Under the Reign of Minh Mạng (1820-1841): Central Policies and Local Response. SEAP Publications. pp. 34–. ISBN 978-0-87727-138-3.

- ↑ Choi Byung Wook (2004). Southern Vietnam Under the Reign of Minh Mạng (1820-1841): Central Policies and Local Response. SEAP Publications. pp. 136–. ISBN 978-0-87727-138-3.

- ↑ Choi Byung Wook (2004). Southern Vietnam Under the Reign of Minh Mạng (1820-1841): Central Policies and Local Response. SEAP Publications. pp. 137–. ISBN 978-0-87727-138-3.

- ↑ Alexander Woodside (1971). Vietnam and the Chinese Model: A Comparative Study of Vietnamese and Chinese Government in the First Half of the Nineteenth Century. Harvard Univ Asia Center. pp. 18–. ISBN 978-0-674-93721-5.

- ↑ Alexander Woodside (1971). Vietnam and the Chinese Model: A Comparative Study of Vietnamese and Chinese Government in the First Half of the Nineteenth Century. Harvard Univ Asia Center. pp. 134–. ISBN 978-0-674-93721-5.

- ↑ Globalization: A View by Vietnamese Consumers Through Wedding Windows. ProQuest. 2008. pp. 34–. ISBN 978-0-549-68091-8.

- ↑ http://angelasancartier.net/ao-dai-vietnams-national-dress

- ↑ http://beyondvictoriana.com/2010/03/14/beyond-victoriana-18-transcultural-tradition-of-the-vietnamese-ao-dai/

- ↑ http://fashion-history.lovetoknow.com/clothing-types-styles/ao-dai

- ↑ http://www.tor.com/2010/10/20/ao-dai-and-i-steampunk-essay/

- ↑ Vietnam. Michelin Travel Publications. 2002. p. 200.

- ↑ Gary Yia Lee; Nicholas Tapp (16 September 2010). Culture and Customs of the Hmong. ABC-CLIO. pp. 138–. ISBN 978-0-313-34527-2.

- ↑ Anthony Reid (2 June 2015). A History of Southeast Asia: Critical Crossroads. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 285–. ISBN 978-0-631-17961-0.

- ↑ Anthony Reid (9 May 1990). Southeast Asia in the Age of Commerce, 1450-1680: The Lands Below the Winds. Yale University Press. pp. 90–. ISBN 978-0-300-04750-9.

- ↑ A. Terry Rambo (2005). Searching for Vietnam: Selected Writings on Vietnamese Culture and Society. Kyoto University Press. p. 64. ISBN 978-1-920901-05-9.

- ↑ Jayne Werner; John K. Whitmore; George Dutton (21 August 2012). Sources of Vietnamese Tradition. Columbia University Press. pp. 295–. ISBN 978-0-231-51110-0.

- ↑ Joseph Marchand: Biography (MEP)

- ↑ Choi Byung Wook Southern Vietnam Under the Reign of Minh Mạng (1820-1841) 2004 Page 151 "Insurrections - The court's radical assimilation policy led to an outbreak of resistance by non-Viet ethnic groups in southern Vietnam. Towards the end of Minh Mạng's reign in 1841, through 1845, southern Vietnam was swept by a series of ..."

- 1 2 http://vi.wikisource.org/wiki/Đế_hệ_thi

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Emperor Minh Mạng. |

Sources

- Hall, D. G. E. (1981) [1955]. A History of South-east Asia. London: Macmillan. ISBN 0-333-24163-0.

- Cady, John F. (1976) [1964]. South East Asia: Its historical development. New York: McGraw Hill. OCLC 15002777.

- Buttinger, Joseph (1958). The Smaller Dragon: A Political History of Vietnam. Praeger. OCLC 411659.

| Preceded by Emperor Gia Long |

Emperor Minh Mạng | Succeeded by Emperor Thiệu Trị |