Jörmungandr

In Norse mythology, Jörmungandr (Old Norse: Jǫrmungandr, pronounced [ˈjɔrmuŋɡandr̥], meaning "huge monster"[1]), often written as Jormungand, or Jörmungand and also known as the Midgard Serpent (Old Norse: Miðgarðsormr), or World Serpent, is a sea serpent, the middle child of the giantess Angrboða and Loki. According to the Prose Edda, Odin took Loki's three children by Angrboða—the wolf Fenrir, Hel, and Jörmungandr—and tossed Jörmungandr into the great ocean that encircles Midgard.[2] The serpent grew so large that it was able to surround the earth and grasp its own tail.[2] As a result, it received the name of the Midgard Serpent or World Serpent. When it releases its tail, Ragnarök will begin. Jörmungandr's arch-enemy is the thunder-god, Thor. It is an example of an ouroboros.

Sources

The major sources for myths about Jörmungandr are the Prose Edda, the skaldic poem Húsdrápa, and the Eddic poems Hymiskviða and Völuspá. Less important sources include kennings in other skaldic poems. For example, in Þórsdrápa, faðir lögseims, "father of the sea-thread", is used as a kenning for Loki. There are also image stones from ancient times depicting the story of Thor fishing for Jörmungandr.

Stories

There are three preserved myths detailing Thor's encounters with Jörmungandr:

Lifting the cat

In one, Thor encounters the serpent in the form of a colossal cat, disguised by the magic of the giant king Útgarða-Loki, who challenges the god to lift the cat as a test of strength. Thor is unable to lift such a monstrous creature as Jörmungandr, but does manage to raise it far enough that it lets go of the ground with one of its four feet.[3] When Útgarða-Loki later explains his deception, he describes Thor's lifting of the cat as an impressive deed.[3]

Thor's fishing trip

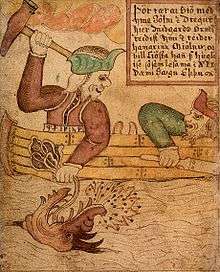

Another encounter comes when Thor goes fishing with the giant Hymir. When Hymir refuses to provide Thor with bait, Thor strikes the head off Hymir's largest ox to use as his bait.[4] They row to a point where Hymir often sat and caught flat fish, where he drew up two whales, but Thor demands to go further out to sea, and does so despite Hymir's warnings.

Thor then prepares a strong line and a large hook and baits it with the ox head, which Jörmungandr bites. Thor pulls the serpent from the water, and the two face one another, Jörmungandr dribbling poison and blood.[4] Hymir goes pale with fear, and as Thor grabs his hammer to kill the serpent, the giant cuts the line, leaving the serpent to sink beneath the waves.[4]

This encounter with Thor seems to have been one of the most popular motifs in Norse art. Four picture stones that have been linked with the myth are the Altuna Runestone, Ardre VIII image stone, the Hørdum stone, and the Gosforth Cross.[5] A stone slab that may be a portion of a second cross at Gosforth also shows a fishing scene using an ox head.[6] Of these, the Ardre VIII stone is the most interesting, with a man entering a house where an ox is standing, and another scene showing two men using a spear to fish.[7] The image on this stone is dated to the 8th[5] or 9th century. If the stone is correctly interpreted as depicting this myth, it demonstrates that the myth was in a stable form for a period of about 500 years prior to the recording of the myth in the Prose Edda around the year 1220.[7]

Final battle

The last meeting between the serpent and Thor is predicted to occur at Ragnarök, when Jörmungandr will come out of the ocean and poison the sky.[8] Thor will kill Jörmungandr and then walk nine paces before falling dead, having been poisoned by the serpent's venom.[8]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Rudolf Simek, Dictionary of Northern Mythology (1993)

- 1 2 Sturluson, Gylfaginning ch. xxxiv, 2008:37.

- 1 2 Sturluson, Gylfaginning ch. xlvi, xlvii, 2008:52, 54.

- 1 2 3 Sturluson, Gylfaginning ch. xlviii, 2008:54-56.

- 1 2 Sørensen 2002:122-123.

- ↑ Fee & Leeming 2001:36.

- 1 2 Sørensen 2002:130.

- 1 2 Sturluson, Gylfaginning ch. li, 2008:61-62.

References

- Fee, Christopher R.; Leeming, David A. (2001). Gods, Heroes, & Kings: The Battle for Mythic Britain. Oxford University Press. p. 36. ISBN 0-19-513479-6.

- Sørensen, Preben M. (2002). "Þorr's Fishing Expedition (Hymiskviða)". In Acker, Paul; Larrington, Carolyne. The Poetic Edda: Essays on Old Norse Mythology. Williams, Kirsten (trans.). Routledge. pp. 119–138. ISBN 0-8153-1660-7.

- Snorri Sturluson; Brodeur, Arthur Gilchrist (transl.) (1916). Prose Edda. The American-Scandinavian Foundation.