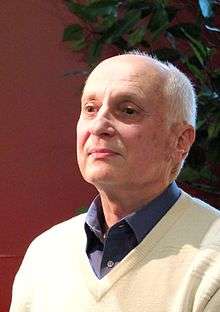

Michel Ocelot

| Michel Ocelot | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

27 October 1943 Villefranche-sur-Mer, French Riviera, France[1] |

| Nationality | French |

| Education |

Ecole régionale des Beaux-Arts, Angers École nationale supérieure des arts décoratifs, Paris California Institute of the Arts, Los Angeles |

| Title | President of ASIFA |

| Term | 1994–1999 |

| Predecessor | Raoul Servais |

| Successor | Abi Feijò |

| Awards | Chevalier of the Légion d'honneur[2] |

Michel Ocelot is a French writer, character designer, storyboard artist and director of animated films and television programs (formerly also animator, background artist, narrator and other roles in earlier works) and a former president of the International Animated Film Association.[3] Though best known for his 1998 début feature Kirikou and the Sorceress, his earlier films and television work had already won Césars[4] and British Academy Film Awards[5] among others and he was made a chevalier of the Légion d'honneur on 23 October 2009, presented to him by Agnès Varda who had been promoted to commandeur earlier the same year.[2]

Biography

He was born in 1943 to a Catholic[6] family then in Villefranche-sur-Mer,[1] on the French Riviera, who relocated to Guinea, West Africa for much of his childhood, moving back to Anjou in France during his adolescence. As a teenager he played with and created toy theatre productions[1] and was inspired to become an animator through viewing Hermína Týrlová's Vzpoura hraček (The Revolt of Toys, 1946)[7][8] and discovering a book on DIY stop motion animation. He was never formally taught animation, however, and instead studied the decorative arts, first at the Ecole régionale des Beaux-Arts in Angers, then the École nationale supérieure des arts décoratifs in Paris and the California Institute of the Arts in Los Angeles.[9] He now lives and operates from an atelier-apartment in Paris.

His œuvre is characterised by having worked in a variety of animation techniques, typically employing a different medium for each new project, but almost exclusively within the genres of fairy tales and fairytale fantasy. Some, such as Kirikou and the Sorceress, are loose adaptations of existing folk tales, others are original stories constructed from the "building blocks" of such tales. He describes the process as "I play with balls that innumerable jugglers have already used for countless centuries. These balls, passed down from hand to hand, are not new. But today I'm the one doing the juggling."[10] Visually, they are characterised by a rigid use, excepting brief transitions between them, of the side-on, straight-on and ¾ viewpoints of silhouette and cutout animation (such as that of Lotte Reiniger[11] and Karel Zeman) even when working in mediums which allow for greater flexibility and dynamic viewpoints. Though often likened to Reiniger,[12] he himself finds her films "rather archaic and not very attractive"[13] and does not list them among his favourites.[9] He also admires the art of ancient Egypt, pottery of ancient Greece, Hokusai and illustrators such as Arthur Rackham, W. Heath Robinson and his brothers and, most of all, Aubrey Beardsley.[14] He was president of the Association international du film d'animation (ASIFA) from 1994 to 2000.

While already a household name in much of continental Europe, and greatly respected by Studio Ghibli's Isao Takahata (who has directed the Japanese dubs of his films), his success in the more conservative markets of the United Kingdom, United States and Germany has been restricted by a mixed reaction to the realistic and non-sexual, but nevertheless omnipresent nudity in his breakout film Kirikou and the Sorceress. Although all of these countries' boards of film classification have approved it as being suitable for all ages, cinemas and TV channels have been reluctant to show it due to the possible backlash from offended parents. In 2007, he gained some further recognition within the English-speaking world by directing a music video for the Icelandic musician Björk, the lead single from her album Volta.

In another, 2008 interview he mentioned as further examples of favourite and influential artistic works Voltaire's letters, The Heron and the Crane, Crac, Father and Daughter, the first part of Grand Illusion, Neighbors, the Eiffel Tower, Millesgården, Persian miniatures, Jean Giraud's free drawing and illustrations by Kay Nielsen.[15]

Filmography

| Year | Title (English) | Format | Medium | Other notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1974 | Le Tabac (The Newsagent) | 1 min. short film | ||

| 1976 | Gédéon (Gideon) | 60 × 5 min. TV series | Cutouts | Based on the comics by Benjamin Rabier |

| 1979 | Les Trois Inventeurs (The Three Inventors) |

13 min. short film | Cutouts | Winner of best animated short at the 34th British Academy Film Awards,[5] Zagreb World Festival of Animated Films[1] 1980 and Odense Film Festival 1981 (tied with Crac !) Extract featured in the "Globe Trotting" segment of the 2003 documentary The Animated Century[16] |

| 1981 | Les Filles de l'égalité (Daughters of Equality) |

1 min. short film | Traditional | Full transfer available on YouTube from production company aaa |

| 1982 | Beyond Oil | 20 min. educational film | Animated segments only; live-action directed by Philippe Vallois | |

| La Légende du pauvre bossu (The Legend of the Poor Hunchback) | 7 min. short film | Animatic | Winner of best animated short at the César Awards 1983[4] | |

| 1983 | La Princesse insensible (The Impassive Princess) |

13 × 4 min. TV series | Mixed[11] | |

| 1987 | Les Quatre Vœux (The Four Wishes) |

5 min. short film | Traditional | Featured in the 1989 package film Outrageous Animation assembled and distributed in cinemas and on home video in North America by Expanded Cinema[17] |

| 1989 | Ciné si | 8 × 12 min. TV series | Silhouettes[9] | Winner of best TV series episode at the Ottawa International Animation Festival 1990 and Annecy International Animated Film Festival 1991 Compiled into Princes et princesses |

| 1992 | Les Contes de la nuit (Tales of the Night) |

26 min. TV special | Silhouettes | Contains "La Belle Fille et le sorcier" ("The Beautiful Girl and the Sorcerer"), "Bergère qui danse" ("The Dancing Shepherdess") and "Le Prince des joyaux" ("Prince of the Gems") |

| 1998 | Kirikou et la sorcière (Kirikou and the Sorceress) |

71 min. feature film | Digital ink and paint | Winner of best animated feature at the Annecy International Animated Film Festival 1999 and best European feature at the British Animation Awards 2002 (tied with Chicken Run) |

| 2000 | Princes et princesses (Princes and Princesses) |

70 min. feature film | Silhouettes | Compilation movie of Ciné si[1] |

| 2005 | Kirikou et les bêtes sauvages (Kirikou and the Wild Beasts) |

75 min. feature film | Digital ink and paint | Co-directed with Bénédicte Galup |

| 2006 | Azur et Asmar (Azur & Asmar: The Princes' Quest) |

90 min. feature film[18] | Computer | Winner of best animated feature at the Zagreb World Festival of Animated Films 2007 Also serves as voice director for the English version |

| 2007 | "Earth Intruders" | 4 min. music video for Björk | Mixed | Nominated for best video at the Q Awards 2007 |

| Kirikou et Karaba (Kirikou and Karaba) |

Play | Musical theatre | ||

| 2008 | L'Invité aux noces (The Wedding Guest) |

Original video | Animatic | |

| 2010 | Dragons et princesses (Dragons and Princesses) |

10 × 13 min. TV series for Canal+ | Silhouettes[19] | Winner of special award for a TV series at the Annecy International Animated Film Festival 2010[20] Compiled into Les Contes de la nuit (2011) |

| 2011 | Les Contes de la nuit (Tales of the Night) |

84 min. feature film | Silhouettes | Compilation movie of Dragons et princesses Premièred in competition for the Golden Bear at the 61st Berlin International Film Festival[21] and screening in competition at the Sitges Film Festival 2011[22] |

| 2012 | Kirikou et les hommes et les femmes (Kirikou and the Men and Women)[23] |

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 Pilling, Jayne (2001). 2D and Beyond. Animation. Hove: RotoVision. pp. 109, 153. ISBN 2-88046-445-5.

- 1 2 Brane, Edouard (26 October 2009). "Le papa de "Kirikou" reçoit la Légion d'Honneur" (in French). AlloCiné. Retrieved 9 June 2010.

- ↑ "Azur & Asmar press pack" (PDF) (Press release). Soda Pictures. 2008. Retrieved 2008-10-05.

- 1 2 http://www.lescesarducinema.com

- 1 2 http://www.bafta.org/awards/film/nominations/?year=1980

- ↑ Leroy, Elodie (2008-01-09). "Interview : Michel Ocelot (Azur et Asmar)". DVDrama.com (in French). p. 3. Retrieved 2008-10-20.

- ↑ "Bring me beauty". Little White Lies. London: Story. 12 (The Tales from Earthsea Issue).

- ↑ "Travelling Cine-meeting 'Remembering and Forgetting'". Asociace českých filmových klubů. p. 1. Retrieved 2008-10-19.

- 1 2 3 Sifianos, Georges (1991). "Une technique idéale". Positif (in French). 370: 102–104.

- ↑ Bazou, Sébastien (2008). "Princes et princesses : Les contes de fées revisités". ArteFake.com (in French). Retrieved 2008-10-20.

- 1 2 Taylor, Richard (1996). The Encyclopedia of Animation Techniques. Oxford: Focal Press. pp. 146–147. ISBN 0-240-51576-5.

- ↑ Fritz, Steve (2008-10-16). "Animated Shorts: Michel Ocelot's Azur and Asmar". Newsarama.com. Imaginova. Retrieved 2008-11-11.

- ↑ Ocelot, Michel (Director) (2008-10-22). Les Secrets de fabrication de Michel Ocelot (Documentary). Paris: France Télévisions.

I'd found Lotte Reiniger's films rather archaic and not very attractive but I thought to myself, 'It'll be fine for children.'

- ↑ Andrews, Nigel (2006-10-22). "Fabulist of filmmaking". FT.com. Retrieved 2008-08-25.

- ↑ Dalquié, Delphine (2008). "Michel Ocelot : Interview". Fascineshion.com. Retrieved 9 February 2011.

- ↑ "The Animated Century". Rembrandt Films. Retrieved 25 August 2011.

- ↑ Cohen, Karl F. (1997). Forbidden Animation: Censored Cartoons And Blacklisted Animators in America. Jefferson: McFarland. pp. 102–104.

- ↑ Recio, Lorenzo (2005-11-21). "Portrait : Michel Ocelot". Court-circuit (in French). Arte. Retrieved 2008-10-08.

- ↑ "Dragons et princesses". Nord-Ouest. 2009. Retrieved 26 November 2009.

- ↑ "2010 award winners". Annecy International Animated Film Festival. Retrieved August 26, 2011.

- ↑ http://www.berlinale.de/en/presse/pressemitteilungen/wettbewerb/wettbewerb-presse-detail_8532.html

- ↑ "Les Contes de la nuit 3D". Sitges Film Festival. 2011. Retrieved 2 September 2011.

- ↑ Leffler, Rebecca (January 27, 2011). ""Rebecca et le sorcier" : Mon interview "animé" avec Michel Ocelot" (in French). Premiere.fr. Retrieved February 10, 2011.

Further reading

- Jouvanceau, Pierre (2004). The Silhouette Film. Pagine di Chiavari. trans. Kitson. Genoa: Le Mani. ISBN 88-8012-299-1.

- Lugt, Peter van der (2008-08-25). "This is Animation". GhibliWorld.com. Retrieved 2008-08-25.

- Pilling, Jayne (2001). "The storyteller". 2D and Beyond. Animation. Hove: RotoVision. pp. 100–109, 153. ISBN 2-88046-445-5.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Michel Ocelot. |

- Official site of Michel Ocelot

- Michel Ocelot at the Internet Movie Database

- Information on and stills from his short films

- Stills from Les Trois Inventeurs and Azur et Asmar

- Interview with Björk and stills from "Earth Intruders" video

- Official site of the Association international du film d'animation

- The Studio Ghibli collection at Walt Disney Studios Japan (Japanese)