Mental health in China

The concept of mental health in China is influenced by Confucian ideology as well as an emphasis on family.[1] In contrast to Western thought, the Chinese emphasize "highly personal duties and social goals" rather than the individual, and personal rights.[1] Failing to fulfill one's duties within the family and society can lead to common symptoms of psychological distress, such as feelings of guilt and shame.[1] Mental health is a growing issue in China with estimates of 100 million sufferers of mental illness.[2]

History

China's first mental institutions were introduced before 1849 by Western missionaries. After the establishment of the People's Republic of China in 1949, the treatment model was indigenized during 1949–1963. During the Cultural Revolution (1964–1976) strong political control governed diagnosis and treatment as well as detention and discharge of mental patients. Later, due to the modernization and reform advocated by Deng Xiaoping, western models of treatment and rehabilitation were gradually introduced by psychiatrists. After more than 25 years of planning and fundraising, American medical missionaries opened the first mental hospital in China in 1898. In 19th century China, the mentally ill were usually confined by their families in a dark room of the house, essentially neglected. If left to wander in the streets, they were often mocked and laughed at, and sometimes stoned. If they did anything wrong, they could be arrested and thrown into prison. Because the mentally ill were largely invisible, some missionaries argued that mental illness was not as prevalent in China as in Europe or the United States. John G. Kerr, MD (1824–1901), an American Presbyterian medical missionary, disagreed – and he worked long and hard to change the treatment of the mentally ill. When he opened his Refuge for the Insane, Kerr declared some new principles: first, insane patients were ill and should not be blamed for their actions; second, they were in a hospital, not a prison; and third, they must be treated as human beings, not as animals. He pledged to conduct a course of treatment based on persuasion rather than force, on freedom rather than restraint, and on a healthy outdoor life with a maximum of rest, warm baths, and kindness. He also wanted to provide patients with gainful employment wherever possible. The directors of the Canton refuge worked closely with local Chinese officials and local police, who did not know how to handle insane people and were glad to refer them in large numbers to the refuge. 6 Chinese officials paid the refuge an annual allowance for taking care of the patients. Local families also brought in patients, and some were sent from Hong Kong by the British authorities. The hospital was eventually expanded to 500 beds, and it operated with considerable success until it finally closed in 1937.[3]

Current

A variety of conflicting factors explain why China continues to lag behind in terms of mental health services. These factors include the balance between human rights and political control, a cultural reticence against acknowledging mental illness and the lack of qualified staff.

Political infringement on human rights

Practices enacted during the Communist Era prevented mental health violations from being exposed. Historically, Maoist and Marxist writings denounced mental illness as a "capitalist evil" that should not exist in a socialist state. Similar misinformed statements were made by the vice minister of public health during the early 1980s, Tan Yunhe, and by workers at the Beijing branch of the Chinese Medical Association.[4] The view of mental illness as a political evil rather than a disease with very human aspects prevents developments in psychiatry, psychotherapy and other integrative healing techniques present in the West. It took 27 years to pass the Mental Health Code in 2013,[5] which prevented patients from being hospitalized against their will. From 1995 to 1999, leadership over developing the law was passed from academic circles to the Ministry of Health (China), consisting primarily of psychiatrists, legal experts and public health experts.[6] This meant that other factions, such as professional groups and individuals involved with the mentally ill had no say in the law. The division of responsibility from academia to government institution shows that only uppermost factions have influence in swaying legislation regarding mental health and is also disorganized since the issue is passed around between organizations until one takes responsibility. Currently, government censorship of dissenting opinions remains a problem because the majority of abuses in psychiatric hospitals remains in secret. Ankang (asylum) hospitals in major urban areas such as Beijing, Hangzhou and Chengdu are psychiatric facilities that provide care for anyone deemed politically subversive or a threat to social stability regardless of mental illness. A significant number of inpatients are Falun gong practitioners or political prisoners. Patients are subjected to treatments such as foot shocks, force feeding, beatings and injections of chemicals that harm the nervous system; ironically, they oftentimes become mentally ill once they leave the institution.[7] Human rights organizations in the United States have reported abuse within China's hospital system. Although China's government has taken action to prioritize mental health by legislation such as the 686 Rule and Mental Health Code,[5] the results of implementing these statutes comes over time.

Cultural reticence

The Chinese reluctance to address mental illness and psychiatry stems from the limited extent to which health care professionals and public health officials are involved with the issue. The US Rural Health Systems Delegation's 1978 visit to a rural inpatient teaching institution revealed patients bound in locked isolation rooms by their legs and hands; when asked about the social nature of mental illness, workers claimed that psychiatry is a purely biological discipline independent of social wellbeing.[8] The workers' attitudes view mental illness merely as neurosis, reflecting the perception that diseases of the mind do not need to be treated holistically in a communal context. That neurosis, a diagnosis of a mild mental illness not caused by disease, is still used as a classification for most anxiety, factitious, and somatoform disorders in China shows that the standards of diagnosis for mental illness have not been updated.

Lack of qualified staff

China has 17,000 certified psychologists, which is ten percent of that of other developed countries per capita.[9] Some 100 million Chinese have mental illnesses, with varying degrees of intensity.[9] Chinese culture emphasizes stoicism, internal confidence, humility, hard work and diligence. These characteristics may make it difficult to be vulnerable or to admit to having a psychiatric illness.[10] Patients have already taken a big leap of faith when they admit to having a psychiatric disorder, yet those that do take the first step to obtain treatment are not in luck, either. China averages one psychologist for every 83,000 people, and some of these psychologists are not board-licensed or certified to diagnose illness. Patients leave the clinics with false diagnoses and often do not return for follow-up treatments, detrimental to the degenerative nature of many psychiatric disorders.[11] While many licensed psychologists lament the low professional standards of their practice, yet they nonetheless continue to provide short-term counseling.[12] They tend to blame patients' "cultural conservativeness" and concerns of "face" for their flexible application of therapeutic methods.[13]

In 2007 the Chief of China's National Centre for Mental Health, Dr Liu Jin estimated that approximately 50% of outpatient admissions were due to depression.[14] And while issues surrounding living conditions in rural areas have been a known contributor to this, another issue is that of high levels of competition in all levels of schooling. One specific area of concern is that of the suicide rate in China, which stands at approximately 20 per 100,000.[15] The World Health Organization (WHO) states that the rate of suicide is thought to be three to four times higher in rural areas than in urban areas, which is consistent with the most common method, which is poisoning by pesticides, which accounts for 62% of incidences.[15]

The disparity between psychiatric services available between rural and urban areas[5] partially contributes to this statistic, as rural areas have traditionally relied on barefoot doctors since the 1970s for medical advice. These doctors, one of the few modes of healthcare able to reach isolated parts of rural China, are unable to obtain modern medical equipment, much less provide reliable diagnoses for psychiatric illness. Also, the income and education level in rural China averages to be less than that of urban China.[16] This makes it difficult for the rural populace to comprehend mental disorders enough to seek treatment. Furthermore, the nearest psychiatric clinic may be hundreds of kilometers away; families may be unable to afford professional psychiatric treatment for the afflicted.

Laws enacted regarding the state of mental illness

On June 10, 2011, the legal institution of China's State Council published a draft for a new 'mental health law', which includes new regulations concerning the right of patients not to be hospitalized against their will.[17] The draft law promotes the transparency of patient treatment management. Currently, many cases exist in which hospitals are led by financial motives and patients' rights are disregarded. On October 26, 2012 China adopted the law. The law stipulates that a qualified psychiatrist must make the determination of mental illness; that patients can choose whether to receive treatment in most cases; and that only those at risk of harming themselves or others are eligible for compulsory inpatient treatment.[18][19] However, although described as significant, Human Rights Watch has also criticised the new law. For example, although it creates some rights for detained patients to request a second opinion from another state psychiatrist and then an independent psychiatrist, there is no right to a legal hearing such as a mental health tribunal and no guarantee of legal representation.[20]

Collaboration

Since 1993, the WHO has been collaborating with China in the development of a national mental health information system. "These efforts included adapting the NKI/WHO Mental Health Information System to the needs of China, training visiting scientists, and providing continuous support to the project. In January 1995, the Center was notified that the System has been approved by the Ministry of Health for use nationwide."[21]

See also

- Chinese Society of Psychiatry

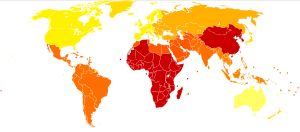

- Global mental health

- Mental health in the Middle East

- Mental health in Southeast Africa

- Political abuse of psychiatry § China

References

- 1 2 3 Hsiao, F., Klimidis, S., Minas, H., & Tan, E. (2006). Cultural attribution of mental health suffering in Chinese societies: the views of Chinese patients with mental illness and their caregivers. Journal Of Clinical Nursing, 15(8), 998-1006. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2702.2006.01331.x

- ↑ Moore, Malcolm. "China has 100 million people with mental illness." The Telegraph. Telegraph Media Group, 28 Apr 209. Web. 18 Feb 2013. <http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/asia/china/5235487/China-has-100-million-people-with-mental-illness.html>.

- ↑ Nava Blum, Elizabeth Fee. American Journal of Public Health. Washington: Sep 2008. Vol. 98, Iss. 9; pg. 1593, 1 pgs

- ↑ Rural Health in the People's Republic of China: Report of a Visit by the Rural Health Systems Delegation, June 1978. Bethesda, MD: U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services. 1980.

- 1 2 3 Chen, Molly. "Abuse of Mentally Ill in China". Mental Health in China. Weebly. Retrieved 16 April 2016.

- ↑ Phillips, M. R., Chen, H., Diesfeld, K., Xie, B., Cheng, H. G., Mellsop, G., & Liu, X (2013). "China's New Mental Health Law: Reframing Involuntary Treatment". American Journal of Psychiatry AJP. 170 (6): 588–591. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.12121559.

- ↑ Mingde (11 January 2015). "Dark Secrets of China's "Ankang" Psychiatric Hospitals". Falun Dafa Minghui.org.

- ↑ Rural Health in the People's Republic of China: Report of a Visit by the Rural Health Systems Delegation, June 1978. Bethesda, MD: U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services. 1980.

- 1 2 "And now the 50-minute hour: Mental health in China". The Economist. 2007-08-18. p. 35. Retrieved 2007-08-18.

- ↑ Sue, S., & Sue, D. W. (1971). "Chinese-American personality and mental health". Amerasia Journal. 1 (2): 36–49.

- ↑ Chen, Molly. "Abuse of Mentally Ill in China". Mental Health in China. Weebly. Retrieved 16 April 2016.

- ↑ Chang, D.F. et al. (2005). "Letting a Hundred Flowers Bloom: Counseling and Psychotherapy in the People's Republic of China". Journal of Mental Health Counseling 27 (2): 104-116.

- ↑ Hizi, Gil. (2016). "Evading chronicity: paradoxes in counseling psychology in contemporary China". Asian Anthropology. 15 (1): 68-81.

- ↑ http://www.abc.net.au/worldtoday/content/2007/s2105125.htm

- 1 2 http://www.who.int/mental_health/resources/suicide_prevention_asia.pdf

- ↑ Wu, N. (2014, August 19). Income inequality in China and the urban-rural divide - Journalist's Resource. Retrieved April 14, 2016, from http://journalistsresource.org/studies/international/china/income-inequality-todays-china

- ↑ 中国出台法律防止"被精神病"侵犯人权 - China published a law, guarding against the violation of human rights as mental patients are hospitalized by force (bilingual), Thinking Chinese, June 13, 2011

- ↑ "China adopts mental health law to curb forced treatment". Reuters. 2012-10-26. Retrieved 2012-10-27.

- ↑ "China Voice: Mental health law can better protect human rights". Xinhua. 2012-10-25. Retrieved 2012-10-27.

- ↑ China: End Arbitrary Detention in Mental Health Institutions Human Rights Watch, May 3, 2013

- ↑ "World Health Organization Collaborating Center for Training and Research in Mental Health and in the Prevention of Substance Abuse". WHO Collaborating Center at NKI. Archived from the original on 2012-02-18. Retrieved 2016-10-20.

Further reading

- Normal and Abnormal Behavior in Chinese Culture (1981) edited by Arthur Kleinman and Tsung-yi Lin

- Chinese Societies and Mental Health (1995) edited by Tsung-yi Lin, Wen-shing Tseng, and Eng-kung Yeh

- Mental health care in China (1995) By Veronica Pearson

- Narcotic Culture - A History of Drugs in China (2004) by Frank Dikötter, Lars Laamann and Zhou Xun

External links

- Chinese Mental Health Network (中华精神卫生网) (Chinese)