Melanocyte

| Melanocyte | |

|---|---|

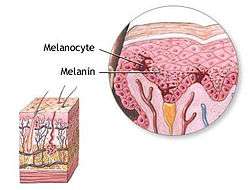

Melanocyte and melanin. | |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | melanocytus |

| MeSH | Melanocytes |

| Code | TH H2.00.03.0.01016 |

Melanocytes (![]() i/məˈlænəˌsaɪt, -noʊ-/ or /ˈmɛlənəˌsaɪt, -noʊ-/[1][2]) are melanin-producing neural-crest derived[3] cells located in the bottom layer (the stratum basale) of the skin's epidermis, the middle layer of the eye (the uvea),[4] the inner ear,[5] meninges,[6] bones,[7] and heart.[8] Melanin is the pigment primarily responsible for skin color. Once synthesised, melanin is contained in a special organelle called a melanosome and moved along arm-like structures called dendrites, so as to reach the keratinocytes.

i/məˈlænəˌsaɪt, -noʊ-/ or /ˈmɛlənəˌsaɪt, -noʊ-/[1][2]) are melanin-producing neural-crest derived[3] cells located in the bottom layer (the stratum basale) of the skin's epidermis, the middle layer of the eye (the uvea),[4] the inner ear,[5] meninges,[6] bones,[7] and heart.[8] Melanin is the pigment primarily responsible for skin color. Once synthesised, melanin is contained in a special organelle called a melanosome and moved along arm-like structures called dendrites, so as to reach the keratinocytes.

Melanogenesis

Through a process called melanogenesis, these cells produce melanin, which is a pigment found in the skin, eyes, and hair. This melanogenesis leads to a long-lasting pigmentation, which is in contrast to the pigmentation that originates from oxidation of already-existing melanin.

There are both basal and activated levels of melanogenesis; in general, lighter-skinned people have low basal levels of melanogenesis. Exposure to UV-B radiation causes an increased melanogenesis. The purpose of the melanogenesis is to protect the hypodermis, the layer under the skin, from the UV-B light that can damage it (DNA photodamage). The color of the melanin is dark, allowing it to absorb a majority of the UV-B light and block it from passing through this skin layer.[9]

Since the action spectrum of sunburn and melanogenesis are virtually identical, they are assumed to be induced by the same mechanism.[10] The agreement of the action spectrum with the absorption spectrum of DNA points towards the formation of cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers (CPDs) - direct DNA damage.

Typically, between 1000 and 2000 melanocytes per square millimeter of skin are found. Melanocytes comprise from 5% to 10% of the cells in the basal layer of epidermis. Although their size can vary, melanocytes are typically 7 μm in length.

The difference in skin color between lightly and darkly pigmented individuals is due not to the number (quantity) of melanocytes in their skin, but to the melanocytes' level of activity (quantity and relative amounts of eumelanin and pheomelanin). This process is under hormonal control, including the MSH and ACTH peptides that are produced from the precursor proopiomelanocortin.

People with oculocutaneous albinism typically have a very low level of melanin production. Albinism is often but not always related to the TYR gene coding the tyrosinase enzyme. Tyrosinase is required for melanocytes to produce melanin from the amino acid tyrosine.[11] Albinism may be caused by a number of other genes as well, like OCA2,[12] SLC45A2,[13] TYRP1,[14] and HPS1[15] to name some. In all, already 17 types of oculocutaneous albinism have been recognized.[16] Each gene is related to different protein having a role in pigment production.

People with Chediak Higashi Syndrome have a buildup of melanin granules due to abnormal function of microtubules.

Stimulations

Numerous stimuli are able to alter melanogenesis, or the production of melanin by cultured melanocytes, although the method by which it works is not fully understood. Certain melanocortins have been shown in laboratory testing to have effect on appetite and sexual activity in mice.[17] Vitamin D metabolites, retinoids, melanocyte-stimulating hormone, forskolin, cholera toxin, isobutylmethylxanthine, diacylglycerol analogues, and UV irradiation all trigger melanogenesis and, in turn, pigmentation.[18] Increased melanin production is seen in conditions where Adrenocorticotropic Hormone (ACTH) is elevated, such as Cushing's disease. This is mainly a consequence of alpha-MSH being secreted along with the hormone associated with reproductive tendencies in primates. Alpha-MSH is a cleavage product of ACTH that has an equal affinity for the MC1 receptor on melanocytes as ACTH.[19]

Melanosomes are vesicles that package the chemical inside a plasma membrane. The melanosomes are organized as a cap protecting the nucleus of the keratinocyte.

When ultraviolet rays penetrate the skin and damage DNA, thymidine dinucleotide (pTpT) fragments from damaged DNA will trigger melanogenesis[20] and cause the melanocyte to produce melanosomes, which are then transferred by dendrites to the top layer of keratinocytes.

Pathology

See also

- Chromatophore (the pigment cell type found in poikilotherm animals)

- Eye color

- Melanocytic tumors of uncertain malignant potential

- Melanoma

- Mole (skin marking)

- Nevus depigmentosus

- Tanning activator

- Vitiligo

References

- ↑ "Melanocyte". Oxford Dictionaries. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 2016-01-20.

- ↑ "Melanocyte". Merriam-Webster Dictionary.

- ↑ Cramer, SF (February 1991). "The origin of epidermal melanocytes. Implications for the histogenesis of nevi and melanomas.". Archives of pathology & laboratory medicine. 115 (2): 115–9. PMID 1992974.

- ↑ Barden H, Levine S (1983). "Histochemical observations on rodent brain melanin". Brain Research Bulletin. 10 (6): 847–851. doi:10.1016/0361-9230(83)90218-6. PMID 6616275.

- ↑ Markert CL, Silvers WK (1956). "The effects of genotype and cell environment on melanoblast differentiation in the house mouse". Genetics. 41 (3): 429–450. PMC 1209793

. PMID 17247639.

. PMID 17247639. - ↑ Mintz B (1971). "Clonal basis of mammalian differentiation". Symposia of the Society for Experimental Biology. 25: 345–370. PMID 4940552.

- ↑ Nichols SE, Reams WM (1969). "The occurrence and morphogenesis of melanocytes in the connective tissues of the PET/MCV mouse strain". Journal of Embryology and Experimental Morphology. 8: 24–32. PMID 14426921.

- ↑ Theriault LL, Hurley LS (1970). "Ultrastructure of developing melanosomes in C57 black and pallid mice". Developmental Biology. 23 (2): 261–275. doi:10.1016/0012-1606(70)90098-9. PMID 5476812.

- ↑ Agar N, Young AR (2005). "Melanogenesis: a photoprotective response to DNA damage?". Mutation Research. 571 (1–2): 121–32. doi:10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2004.11.016. PMID 15748643.

- ↑ Parrish JA, Jaenicke KF, Anderson RR (1982). "Erythema And Melanogenesis Action Spectra Of Normal Human Skin". Photochemistry and Photobiology. 36 (2): 187–191. doi:10.1111/j.1751-1097.1982.tb04362.x. PMID 7122713.

- ↑ "TYR". National Institutes of Health. Retrieved 23 June 2013.

- ↑ "OCA2". National Institutes of Health. Retrieved 25 March 2016.

- ↑ "SLC45A2". National Institutes of Health. Retrieved 25 March 2016.

- ↑ "TYRP1". National Institutes of Health. Retrieved 25 March 2016.

- ↑ "HPS1". National Institutes of Health. Retrieved 25 March 2016.

- ↑ "Increasing the complexity: new genes and new types of albinism". Wiley Online Library / Pigment Cell & Melanoma Research. Retrieved 25 March 2016.

- ↑ Thompson C, Berger A (2000). "Agent provocateur pursues happiness". BMJ. 321 (7252): 12. doi:10.1136/bmj.321.7252.12. PMC 1127681

. PMID 10875824.

. PMID 10875824. - ↑ Roméro-Graillet C, Aberdam E, Biagoli N, Massabni W, Ortonne JP, Ballotti R (1996). "Ultraviolet B radiation acts through the nitric oxide and cGMP signal transduction pathway to stimulate melanogenesis in human melanocytes". Journal of Biological Chemistry. 271 (45): 28052–6. doi:10.1074/jbc.271.45.28052. PMID 8910416.

- ↑ Abdel-Malek, Z.; Scott, M. C.; Suzuki, I.; Tada, A.; Im, S.; Lamoreux, L.; Ito, S.; Barsh, G.; Hearing, V. J. (2000-01-01). "The melanocortin-1 receptor is a key regulator of human cutaneous pigmentation". Pigment Cell Research / Sponsored by the European Society for Pigment Cell Research and the International Pigment Cell Society. 13 Suppl 8: 156–162. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0749.13.s8.28.x. ISSN 0893-5785. PMID 11041375.

- ↑ Eller MS, Maeda T, Magnoni C, Atwal D, Gilchrest BA (1997). "Enhancement of DNA repair in human skin cells by thymidine dinucleotides: evidence for a p53-mediated mammalian SOS response". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 94 (23): 12627–32. doi:10.1073/pnas.94.23.12627. PMC 25061

. PMID 9356500.

. PMID 9356500.

Further reading

- Ito S (2003). "The IFPCS presidential lecture: a chemist's view of melanogenesis". Pigment Cell Research. 16 (3): 230–6. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0749.2003.00037.x. PMID 12753395.

- Millington GW (2006). "Proopiomelanocortin (POMC): the cutaneous roles of its melanocortin products and receptors". Clinical and Experimental Dermatology. 31 (3): 407–12. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2230.2006.02128.x. PMID 16681590.

External links

- Histology image: 07903loa – Histology Learning System at Boston University - "Eye: fovea, RPE"

- Histology image: 08103loa – Histology Learning System at Boston University - "Integument: pigmented skin"