Megantereon

| Megantereon Temporal range: Early Pliocene to Middle Pleistocene | |

|---|---|

| |

| M. cultridens skeleton | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Family: | Felidae |

| Subfamily: | †Machairodontinae |

| Tribe: | †Smilodontini |

| Genus: | †Megantereon Croizet & Jobert, 1828 |

Megantereon was a genus of prehistoric machairodontine saber-toothed cat that lived in North America, Eurasia, and Africa. It may have been the ancestor of Smilodon.

Taxonomy

Fossil fragments have been found in Africa, Eurasia, and North America. The oldest confirmed records of Megantereon are known from the Pliocene of North America and are dated to about 4.5 million years. About 3-3.5 million years ago, it is firmly recorded also from Africa (for example, in Kenya[1]), about 2.5 to 2 million years ago also from Asia. In Europe the oldest remains are known from Les Etouaries (France), a site which is now dated to less than 2.5 million years old. Therefore, a North American origin of Megantereon has been suggested. However, recent findings of fragmentary fossils from Kenya and Chad, which are dated to about 5.7 and 7 million years, respectively, are probably from Megantereon. If these identifications are right, they would represent the oldest Megantereon fossils in the world. The new findings therefore indicate an origin of Megantereon in the Late Miocene of Africa.[2]

Therefore, the true number of species may be less than the full list of described species reproduced below.[3]

- Megantereon cultridens (Cuvier, 1824) (type species)

- Megantereon ekidoit Werdelin & Lewis, 2000

- Megantereon hesperus (Gazin, 1933)

- Megantereon inexpectatus Teilhard de Chardin, 1939

- Megantereon microta Zhu et. al., 2015[4]

- Megantereon nihowanensis Teilhard de Chardin & Piveteau, 1930

- Megantereon vakhshensis Sarapov, 1986

- Megantereon whitei Broom, 1937

Evolution

At the end of the Pliocene it evolved into the larger Smilodon in North America, while it survived in the Old World until the middle Pleistocene. The youngest remains of Megantereon from east Africa are about 1.5 million years old. In southern Africa, the genus is recorded from Elandsfontein, a site dated to around 700,000-400,000 years old. Remains from Untermaßfeld show that Megantereon lived until 900,000 years ago in Europe. In Asia, it may have survived until 500,000 years ago, as it is recorded together with Homo erectus at the famous site of Zho-Khou-Dien in China. The only full skeleton was found in Senéze, France.

Description

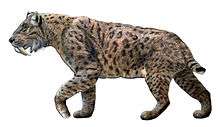

Megantereon was built like a large modern jaguar, but somewhat heavier. It had stocky forelimbs with the lower half of these forelimbs lion-sized. It had large neck muscles designed to deliver a powerful shearing bite. The elongated upper canines were protected by flanges at the mandible. Mauricio Anton's reconstruction in The Big Cats and their Fossil Relatives depicts the full specimen found at Seneze in France as 72 centimetres (28 in) at the shoulder. The largest specimens, with an estimated body weight of 90–150 kilograms (200–330 lb) (average 120 kilograms (260 lb)), are known from India. Medium-sized species of Megantereon are known from other parts of Eurasia and the Pliocene of North America. The smallest species from Africa and the lower Pleistocene of Europe have been estimated to only 60–70 kilograms (130–150 lb).[5] However, these estimations were obtained from comparisons of the carnassial teeth. Younger estimations, which are based on the postcranial skeleton, lead to body weights of about 100 kilograms (220 lb) for the smaller specimens.[6] In agreement with that, more recent sources estimated Megantereon from the European lower Pleistocene at 100–160 kilograms (220–350 lb).[7]

Palaeobiology

In Europe, Megantereon may have preyed on larger artiodactyls, horses or the young of rhinos and elephants.[8] Despite its size, Megantereon would have also likely been scansorial and therefore able to climb trees, like the earlier Promegantereon (thought to be its ancestor), and unlike the later Smilodon, which is believed to have spent its time on the ground.[9] In addition to this, Megantereon had relatively small carnassial teeth, indicating that once making a kill, it would have eaten its prey at a leisurely pace, either hidden deep in bushes or up in trees away from potential rivals. This indicates a similarity in lifestyle with modern leopards in that it was probably solitary.[10]

It is unlikely that Megantereon simply bit its prey as the long, sabre-teeth that Smilodon is famed for are not strong enough to leave buried inside a struggling prey animal: the teeth would break off. It is possible that they bit their prey and then allowed it to bleed to death, but then they would have to protect that animal from other predators and thus their tactic for killing remains uncertain.

It is now generally thought that Megantereon, like other saber-toothed cats, used its long saber teeth to deliver a killing throat bite, severing most of the major nerves and blood vessels. While the teeth would still risk damage, the prey animal would be killed quickly enough that any struggles would be feeble at best.[11]

At Dmanisi, Georgia, evidence also exists in the form of a Homo erectus skull that Megantereon interacted with hominids as well. The skull, labelled as D2280, shows wounds to the occipital that match the dimensions of the sabre-teeth of Megantereon. From the placement of the bite marks, it can be implied that the hominid was attacked from the front and top of the skull, and that the bite was likely placed by a cat that saw the hominid as a rival: other machairodont bites have been found on rival predators in past fossil discoveries, including other machairodonts; wounds indicative of aggressive behavior towards perceived competition. The hominid likely managed to escape the Megantereon, as no evidence points to predation or scavenging, but the resulting wounds proved fatal.[12] Further evidence exists in the form of carbon isotope ratios in the teeth for Megantereon being a hunter of hominids at Swartkrans. When compared with its fellow machairodont, Dinofelis, which shared the same environment, it was discovered that Megantereon was more likely to prey on hominids than Dinofelis, which preferred to hunt grazing animals based on carbon isotope ratios of its own teeth.[13]

References

- ↑ Lewis, Margaret E.; Werdelin, Lars (November 2000). "Carnivora From the South Turkwel Hominid Site, Northern Kenya". Journal of Paleontology. The Paleontological Society. 74 (6): 1173. doi:10.1666/0022-3360(2000)074<1173:cftsth>2.0.co;2.

- ↑ De Bonis, L., Peigne, S., Mackaye, H. T., Likius, A., Vignaud, P., Brunet, M. (2010). New sabre-toothed cats in the Late Miocene of Toros Menalla (Chad). Systematic palaeontology (Vertebrate palaeontology) Comptes Rendus Palevol 9, 221-227.

- ↑ Turner, A (1987). "Megantereon cultridens (Cuvier) (Mammalia, Felidae, Machairodontinae) from Plio-Pleistocene Deposits in Africa and Eurasia, with Comments on Dispersal and the Possibility of a New World Origin". Journal of Paleontology. 61 (6): 1256–1268. JSTOR 1305213.

- ↑ Min Zhu, Yaling Yan, Yihong Liu, Zhilu Tang, Dagong Qin and Changzhu Jin (2015). "The new Carnivore remains from the Early Pleistocene Yanliang Gigantopithecus fauna, Guangxi, South China". Quaternary International. in press. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2015.01.009.

- ↑ B. M. Navarro and P. Palmqvist: Presence of the African Machairodont Megantereon whitei (Broom, 1937) (Felidae, Carnivora, Mammalia) in the Lower Pleistocene Site of Venta Micena (Orce, Granada, Spain), with some Considerations on the Origin, Evolution and Dispersal of the Genus. Journal of Archaeological Science (1995) 22, 569–582.

- ↑ Navarro, B., M., Palmquist, P., (1996). Presence of the African Saber-toothed Felid Megantereon whitei (Broom, 1937) (Mammalia, Carnivora, Machairodontinae) in Apollonia-1 (Mygdonia Basin, Macedonia, Greece). Journal of Archaeological Science 23, 869–872

- ↑ N. Garcia and E. Virgos: Evolution of community in several carnivore palaeoguilds from the European Pleistocene: the role of intraspecific competition. Lethaia 40 (2007)

- ↑ Per Christiansen, Jan S. Adolfssen. Osteology and ecology of Megantereon cultridens SE311 (Mammalia; Felidae; Machairodontinae), a sabrecat from the Late Pliocene – Early Pleistocene of Senéze, France. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 2007, 151, 833–884. With 29 figures.

- ↑ Anton, Mauricio (2013). Sabertooth.

- ↑ Antón, Mauricio (2013). Sabertooth. Bloomington, Indiana: University of Indiana Press. p. 185. ISBN 9780253010421.

- ↑ Turner, Alan (1997). The Big Cats and their fossil relatives. New York: Columbia University Press. p. 55. ISBN 0-231-10228-3.

- ↑ https://chasingsabretooths.wordpress.com/2013/06/19/ouch-that-hurts-human-sabertooth-interaction-at-dmanisi/

- ↑ http://www.maropeng.co.za/news/entry/dinofelis_hominid_hunter_or_misunderstood_feline

Further reading

- Augustí, Jordi. Mammoths, Sabertooths and Hominids: 65 Million Years of Mammalian Evolution in Europe. New York: Columbia University Press, 2002, ISBN 0-231-11640-3.

- Mol, Dick, Wilrie van Logchem, Kees van Hooijdonk and Remie Bakker. The Saber-Toothed Cat of the North Sea. Uitgeverij DrukWare, Norg 2008, ISBN 978-90-78707-04-2.

- Turner, Alan. The Big Cats and Their Fossil Relatives: An Illustrated Guide to their Evolution and Natural History. Illustrations by Mauricio Anton. New York: Columbia University Press, 1997, ISBN 0-231-10229-1.