History of Iceland

Part of a series on the |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History of Iceland | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Middle Ages | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Modern era | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Related topics | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Timeline | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

The recorded history of Iceland began with the settlement by Viking explorers and their slaves from the east, particularly Norway and the British Isles, in the late ninth century. Iceland was still uninhabited long after the rest of Western Europe had been settled. Recorded settlement has conventionally been dated back to 874, although archaeological evidence indicates Gaelic monks had settled Iceland before that date.

The land was settled quickly, mainly by Norwegians who may have been fleeing conflict or seeking new land to farm. By 930, the chieftains had established a form of governance, the Althing, making it one of the world's oldest parliaments. Towards the end of the tenth century Christianity came to Iceland through the influence of the Norwegian king Olaf Tryggvason. During this time Iceland remained independent, a period known as the Old Commonwealth and Icelandic historians began to document the nation's history in books referred to as sagas of Icelanders. In the early thirteenth century, the internal conflict known as the age of the Sturlungs weakened Iceland, which eventually became subjugated to Norway through the Old Covenant (1262–4), effectively ending the Commonwealth. Norway, in turn, was united with Sweden (1319) and then Denmark (1376). Eventually all of the Nordic states were united in one alliance, the Kalmar Union (1397–1523), but on its dissolution, Iceland fell under Danish rule. The subsequent strict Danish–Icelandic Trade Monopoly in the 17th and 18th centuries was very detrimental to the economy. Iceland's subsequent poverty was aggravated by severe natural disasters like the Móðuharðindin or "Mist Hardships". During this time the population declined.

Iceland remained part of Denmark, but in keeping with the rise of nationalism around Europe in the nineteenth century an independence movement emerged. The Althing, which had been suspended in 1799, was restored in 1844, and Iceland gained sovereignty after World War I, on 1 December 1918. However Iceland shared the Danish Monarchy until World War II. Although Iceland was neutral, the allies occupied it without resistance because of its strategic situation. Since Denmark was under Nazi occupation starting in 1940, Iceland declared itself a fully independent nation; the founding of the Republic of Iceland occurred on 17 June 1944. Following the Second World War Iceland was a founding member of the United Nations and grew rapidly, largely due to fishing, although this was marred by conflicts with other nations like the Cod Wars.

Following rapid financial growth, the 2008–11 Icelandic financial crisis occurred. Iceland still struggles with the aftermath of the financial crisis. Iceland continues to remain outside the European Union and has adopted currency barriers that are almost unique in the history of modern Europe. Tourism now accounts for the second largest source of revenue.

Because of its remoteness, Iceland has been spared the ravages of European wars, but has been affected by other external events, such as the Black Death and the Protestant Reformation imposed by Denmark. Iceland's history has also been marked by a number of natural disasters.

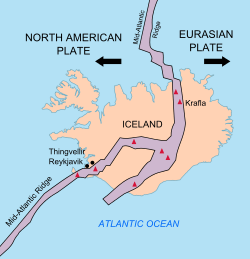

Iceland is also a relatively young country in the geological sense, being formed about 20 million years ago by a series of volcanic eruptions in the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. The oldest stone specimens found in Iceland date back to ca. 16 million years ago.

Geological background

In geological terms, Iceland is a young island. It started to form in the Miocene era about 20 million years ago from a series of volcanic eruptions on the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, where it lies between the North American and Eurasian plates. These plates spread at a rate of approximately 2.5 centimeters per year. [1] This elevated portion of the ridge is known as the Reykjanes Ridge. The volcanic activity is attributed to a hotspot, the Iceland hotspot, which in turn lies over a mantle plume (the Iceland Plume) an anomalously hot rock in the Earth's mantle which is likely to be partly responsible for the island's creation and continued existence. For comparison, it is estimated that other volcanic islands, such as the Faroe Islands have existed for about 55 million years, [2] the Azores (on the same ridge) about 8 million years, [3] and Hawaii less than a million years. [4] The younger rock strata in the southwest of Iceland and the central highlands are only about 700 thousand years old. The geological history of the earth is divided into ice ages, based on temperature and climate. The last glacial period, commonly referred to as The Ice Age is thought to have begun about 110 thousand years ago and ended about 10 thousand years ago. While covered in ice, Iceland's icefalls, fjords and valleys were formed. [5]

Early history

Iceland remained, for a long time, one of the world's last larger islands uninhabited by humans (the others being New Zealand and Madagascar). It has been suggested that the land called Thule by the Greek merchant Pytheas (fourth century BC) was actually Iceland, although it seems highly unlikely considering Pytheas' description of it as an agricultural country with plenty of milk, honey, and fruit: probably Norway, or possibly the Faroe Islands or Shetland. The exact date that humans first reached the island is uncertain. Roman currency dating to the third century have been found in Iceland, but it is unknown whether they were brought there at that time or came later with Vikings after circulating for centuries.[6]

There is some literary evidence that monks and the Papar from a Hiberno-Scottish mission may have settled in Iceland before the arrival of the Norsemen.[7] The twelfth-century scholar Ari Þorgilsson's Íslendingabók states that small bells, corresponding to those used by Irish monks, were found by the settlers. No such artifacts have been discovered by archaeologists, however. Some Icelanders claimed descent from Cerball mac Dúnlainge, King of Osraige in southeastern Ireland, at the time of the Landnámabók's creation.

Settlement (874–930)

Irish monks

The Landnámabók mentions the presence of Irish monks (the Papar) prior to Norse settlement, and states that the monks left behind Irish books, bells and crosiers, among other things. According to the same account, the Irish monks abandoned the country when the Norse arrived, or had left prior to their arrival.

Another source mentioning the Papar is Íslendingabók, dating from between 1122 and 1133. According to this account, the previous inhabitants, a few Irish monks, known as the Papar, left the island since they did not want to live with pagan Norsemen. One theory suggests that those monks were members of a Hiberno-Scottish mission, i.e. Irish and Scottish monks who spread Christianity during the Middle Ages. They may also have been hermits.

Recent archaeological excavations have revealed the ruins of a cabin in Hafnir on the Reykjanes peninsula (close to Keflavík International Airport). Carbon dating reveals that the cabin was abandoned somewhere between 770 and 880, suggesting that Iceland was populated well before 874. This archaeological find may also indicate that the monks left Iceland before the Norse arrived.[8]

Norse discovery

According to the Landnámabók, Iceland was discovered by Naddodd, one of the first settlers in the Faroe Islands, who was sailing from Norway to the Faroes but lost his way and drifted to the east coast of Iceland. Naddodd called the country Snæland "Snowland". Swedish sailor Garðar Svavarsson also accidentally drifted to the coast of Iceland. He discovered that the country was an island and called it Garðarshólmi "Garðar's Islet" and stayed for the winter at Húsavík.

The first Norseman who deliberately sailed to Garðarshólmi was Hrafna-Flóki Vilgerðarson. Flóki settled for one winter at Barðaströnd. After the incredibly cold winter passed, the summer came and the whole island became green, which stunned Flóki. Realizing that this place was in fact habitable, despite the horribly cold winter, and full of useful resources, Flóki restocked his boat. Flóki then continued his journey west when he came upon Greenland, which was relatively close to Iceland, but much more northwest and despite being summer, it still had freezing temperatures. He then returned east to Norway with resources and knowledge.

First settler

The first permanent settler in Iceland is usually considered to have been a Norwegian chieftain named Ingólfr Arnarson and his wife, Hallveig Fróðadóttir. According to the Landnámabók, he threw two carved pillars overboard as he neared land, vowing to settle wherever they landed. He then sailed along the coast until the pillars were found in the southwestern peninsula, now known as Reykjanesskagi. There he settled with his family around 874, in a place he named Reykjarvík "Smoke Cove", probably due to the geothermal steam rising from the earth.

This very place would eventually become the capital and the largest city of modern Iceland. It is recognized, however, that Ingólfr Arnarson may not have been the first one to settle permanently in Iceland — that may have been Náttfari, one of Garðar Svavarsson's men who stayed behind when Garðar returned to Scandinavia.

Much of the above information comes from the Landnámabók, written some three centuries after the settlement. Archeological findings in Reykjavík are consistent with the date given there: there was a settlement in Reykjavík around 870.

Settlement

According to Landnámabók, Ingólfr was followed by many more Norse chieftains, their families and slaves who settled all the inhabitable areas of the island in the next decades. Archeological evidence strongly suggests that the timing is roughly accurate; "that the whole country was occupied within a couple of decades towards the end of the 9th century."[9] These people were primarily of Norwegian, Irish and Scottish origin. Some of the Irish and Scots were slaves and servants of the Norse chiefs according to the sagas of Icelanders and the Landnámabók and other documents. Some settlers coming from the British Isles were "Hiberno-Norse," with cultural and family connections both to the coastal and island areas of Ireland and/or Scotland and to Norway.

The traditional explanation for the exodus from Norway is that people were fleeing the harsh rule of the Norwegian king Harald Fairhair, whom medieval literary sources credit with the unification of some parts of modern Norway during this period. It is also believed that the western fjords of Norway were simply overcrowded in this period. The settlement of Iceland is thoroughly recorded in the aforementioned Landnámabók, although the book was compiled in the early 12th century when at least 200 years had passed from the age of settlement.

Ari Þorgilsson's Íslendingabók is generally considered more reliable as a source and is probably somewhat older, but it is far less thorough. It does say that Iceland was fully settled within 60 years, which likely means that all arable land had been claimed by various settlers.

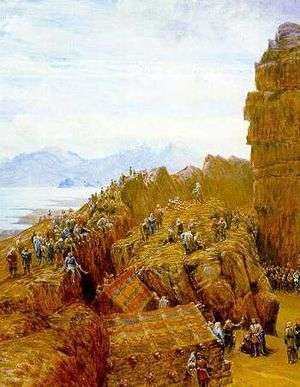

Commonwealth (930–1262)

In 930, the ruling chiefs established an assembly called the Alþingi (Althing). The parliament convened each summer at Þingvellir, where representative chieftains (Goðorðsmenn or Goðar) amended laws, settled disputes and appointed juries to judge lawsuits. Laws were not written down, but were instead memorized by an elected Lawspeaker (lǫgsǫgumaðr).

The Alþingi is sometimes stated to be the world's oldest existing parliament. Importantly, there was no central executive power, and therefore laws were enforced only by the people. This gave rise to feuds, which provided the writers of the sagas with plenty of material.

Iceland enjoyed a mostly uninterrupted period of growth in its commonwealth years. Settlements from that era have been found in southwest Greenland and eastern Canada, and sagas such as Saga of Erik the Red and Greenland saga speak of the settlers' exploits.

Christianisation

The settlers of Iceland were predominantly pagans and worshipped the Norse gods, among them Odin, Thor, Freyr and Freyja. By the tenth century, political pressure from Europe to convert to Christianity mounted. As the end of the first millennium grew near, many prominent Icelanders had accepted the new faith.

In the year 1000, as a civil war between the religious groups seemed likely, the Alþingi appointed one of the chieftains, Thorgeir Ljosvetningagodi, to decide the issue of religion by arbitration. He decided that the country should convert to Christianity as a whole, but that pagans would be allowed to worship privately.

The first Icelandic bishop, Ísleifur Gissurarson, was consecrated by bishop Adalbert of Hamburg in 1056.

Civil war and the end of the commonwealth

During the 11th and 12th centuries, the centralization of power had worn down the institutions of the Commonwealth, as the former, notable independence of local farmers and chieftains gave way to the growing power of a handful of families and their leaders. The period from around 1200 to 1262 is generally known as age of the Sturlungs. This refers to Sturla Þórðarson and his sons Þórður Sturluson, Sighvatr Sturluson, and Snorri Sturluson, who were one of two main clans fighting for power over Iceland, causing havoc in a land inhabited almost entirely by farmers who could ill-afford to travel far from their farms, across the island to fight for their leaders.

In 1220, Snorri Sturluson became a vassal of Haakon IV of Norway; his nephew Sturla Sighvatsson also became a vassal in 1235. Sturla used the power and influence of the Sturlungar family clan to wage war against the other clans in Iceland. After decades of conflict, the Icelandic chieftains agreed to accept the sovereignty of Norway and signed the Old Covenant (Gamli sáttmáli) establishing a union with the Norwegian monarchy.

Iceland under Norwegian and Danish kings (1262–1944)

Norwegian rule

Little changed in the decades following the treaty. Norway's consolidation of power in Iceland was slow, and the Althing intended to hold onto its legislative and judicial power. Nonetheless, the Christian clergy had unique opportunities to accumulate wealth via the tithe, and power gradually shifted to ecclesiastical authorities as Iceland's two bishops in Skálholt and Hólar acquired land at the expense of the old chieftains.

Around the time Iceland became a vassal state of Norway, a climate shift occurred—a phenomenon now called the Little Ice Age. Areas near the Arctic Circle such as Iceland and Greenland began to have shorter growing seasons and colder winters. Since Iceland had marginal farmland in good times, the climate change resulted in hardship for the population.[10] A serfdom-like institution called the vistarband developed, in which peasants were bound to landowners for a year at a time.

It became more difficult to raise barley, the primary cereal crop, and livestock required additional fodder to survive longer and colder winters. Icelanders began to trade for grain from continental Europe — an expensive proposition. Church fast days increased demand for dried codfish, which was easily caught and prepared for export, and the cod trade became an important part of the economy.[10]

Danish rule

Iceland remained under Norwegian kingship until 1380, when the death of Olaf II of Denmark extinguished the Norwegian male royal line. Norway (and thus Iceland) then became part of the Kalmar Union, along with Sweden and Denmark, with Denmark as the dominant power. Unlike Norway, Denmark did not need Iceland's fish and homespun wool. This created a dramatic deficit in Iceland's trade, and as a result, no new ships for continental trading were built. The small Greenland colony, established in the late 10th century, died out completely before 1500.

With the introduction of absolute monarchy in Denmark–Norway in 1660 under Frederick III of Denmark, the Icelanders relinquished their autonomy to the crown, including the right to initiate and consent to legislation. Denmark, however, did not provide much protection to Iceland, which was raided in 1627 by a Barbary pirate fleet that abducted almost 300 Icelanders into slavery, in an episode known as the Turkish Abductions.

Reformation and Danish trade monopoly

By the middle of the 16th century, Christian III of Denmark began to impose Lutheranism on his subjects. Jón Arason and Ögmundur Pálsson, the Catholic bishops of Skálholt and Hólar respectively, opposed Christian's efforts at promoting the Protestant Reformation in Iceland. Ögmundur was deported by Danish officials in 1541, but Jón Arason put up a fight.

Opposition to the reformation ended in 1550 when Jón Arason was captured after being defeated in the Battle of Sauðafell by loyalist forces under the leadership of Daði Guðmundsson. Jón Arason and his two sons were subsequently beheaded in Skálholt. Following this, the Icelanders became Lutherans and remain largely so to this day.

In 1602, Iceland was forbidden to trade with countries other than Denmark, by order of the Danish government, which at this time pursued mercantilist policies. The Danish–Icelandic Trade Monopoly would remain in effect until 1786.

The eruption of Laki

In the 18th century, climatic conditions in Iceland reached an all-time low since the original settlement. On top of this, Laki erupted in 1783, spitting out 12.5 cubic kilometres (3.0 cu mi) of lava. Floods, ash, and fumes killed 9000 people and 80% of the livestock. The ensuing starvation killed a quarter of Iceland's population.[11] This period is known as the Móðuharðindin "Mist Hardships".

When the two kingdoms of Denmark and Norway were separated by the Treaty of Kiel in 1814 following the Napoleonic Wars, Denmark kept Iceland as a dependency.

Independence movement

Throughout the 19th century, the country's climate continued to grow worse, resulting in mass emigration to the New World, particularly Manitoba in Canada. However, a new national consciousness was revived in Iceland, inspired by romantic nationalist ideas from continental Europe. This revival was spearheaded by the Fjölnismenn, a group of Danish-educated Icelandic intellectuals.

An independence movement developed under the leadership of a lawyer named Jón Sigurðsson. In 1843 a new Althing was founded as a consultative assembly. It claimed continuity with the Althing of the Icelandic Commonwealth, which had remained for centuries as a judicial body and been abolished in 1800.

Home rule and sovereignty

In 1874, a thousand years after the first acknowledged settlement, Denmark granted Iceland a constitution and home rule, which again was expanded in 1904. The constitution was revised in 1903, and a minister for Icelandic affairs, residing in Reykjavík, was made responsible to the Althing, the first of whom was Hannes Hafstein.

The Act of Union, a December 1, 1918, agreement with Denmark, recognized Iceland as a fully sovereign state — the Kingdom of Iceland – joined with Denmark in a personal union with the Danish king. Iceland established its own flag. Denmark was to represent its foreign affairs and defense interests. Iceland had no military or naval forces and Denmark was to give notice to other countries that it was permanently neutral. The Act would be up for revision in 1940 and could be revoked three years later if agreement was not reached. By the 1930s the consensus in Iceland was to seek complete independence by 1944 at the latest.[12]

World War I

In the quarter of a century preceding the War, Iceland prospered. Iceland became more isolated during World War I and suffered a significant decline in living standards.[13][14] The treasury became highly indebted, there was a shortage of food and fears over an imminent famine.[13][14][15]

Iceland was part of neutral Denmark during the War. Icelanders were, in general, sympathetic to the cause of the Allies. Iceland also traded significantly with the United Kingdom during the War, as Iceland found itself within its sphere of influence.[16][17][18] In their attempts to stop the Icelanders from trading with the Germans indirectly, the British imposed costly and time-consuming constraints on Icelandic exports going to the Nordic countries.[17][19] There is no evidence of any German plans to invade Iceland during the war.[17]

1.245 Icelanders, Icelandic Americans and Icelandic Canadians were registered as soldiers during World War I. 989 fought for Canada whereas 256 fought for the United States. 391 of the combatants were born in Iceland, the rest were of Icelandic descent. 10 women of Icelandic descent and 4 women born in Iceland served as nurses for the Allies during World War I. At least 144 of the combatants died during World War I (96 in combat, 19 from wounds suffered during combat, 2 from accidents, and 27 from disease), 61 of them were Iceland-born. Ten men were taken as prisoners of war by the Germans.[20]

The War had a lasting impact on Icelandic society and Iceland's external relations. The War led to major government interference in the marketplace that would last until the post-World War II period.[21] Iceland's competent governance of internal affairs and relations with other states while relations with Denmark were interrupted during the War showed that Iceland was capable of acquiring further powers, which resulted in Denmark recognizing Iceland as a fully sovereign state in 1918.[21][22] It has been argued that the thirst for news of the War helped Morgunblaðið to gain a dominant position among Icelandic newspapers.[23]

The Great Depression

Icelandic post-World War I prosperity came to an end with the outbreak of the Great Depression, a severe worldwide economic depression. The Depression hit Iceland hard as the value of exports of plummeted. The total value of Icelandic exports fell from 74 million kronur in 1929 to 48 million in 1932, and was not to rise again to the pre-1930 level until after 1939.[24] Government interference in the economy increased: "Imports were regulated, trade with foreign currency was monopolized by state-owned banks, and loan capital was largely distributed by state-regulated funds".[24] Due to the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War, which cut Iceland's exports of saltfish by half, the Depression lasted in Iceland until the outbreak of World War II when prices for fish exports soared.[24]

World War II

.jpg)

With war looming in spring 1939, Iceland realized its exposed position would be very dangerous in wartime. An all-party government was formed and Lufthansa's request for civilian airplane landing rights was rejected. German ships were all about, however, until the British blockade of Germany stopped that when the war began in September. Iceland demanded Britain allow it to trade with Germany, to no avail.[25]

The occupation of Denmark by Nazi Germany began on April 9, 1940, severing communications between Iceland and Denmark.[26] As a result, on April 10, the Parliament of Iceland took temporary control of foreign affairs, electing a provisional governor, Sveinn Björnsson, who later became the republic's first president. It turned down British offers of protection because that would violate neutrality. Britain and the U.S. opened direct diplomatic relations, as did Sweden and Norway. The German takeover of Norway left Iceland highly exposed; Britain decided it could not risk a German takeover. On May 10, 1940, British military forces began an invasion of Iceland when they sailed into Reykjavík harbour in Operation Fork. There was no resistance, but the government protested against what it called a "flagrant violation" of Icelandic neutrality and Prime Minister Hermann Jónasson called on Icelanders to treat the British troops with the politeness as if they were guests.[26] They behaved accordingly and there were no mishaps. The occupation of Iceland would last throughout the war.[27]

At the peak, the British had 25,000 troops stationed in Iceland,[26] all but eliminating unemployment in the Reykjavík area and other strategically important places. In July 1941, responsibility for Iceland's occupation and defence passed to the United States under a U.S.-Icelandic agreement which included a provision that the U.S. recognize Iceland's absolute independence. The British were replaced by up to 40,000 Americans, who outnumbered all adult Icelandic men. (At the time, Iceland had a population of around 120,000.)[28]

Approximately 159 Icelanders' lives have been confirmed to have been lost in World War II hostilities.[29] Most were killed on cargo and fishing vessels sunk by German aircraft, U-boats or mines.[29][30] An additional 70 Icelanders died at sea during World War II but it has not been confirmed yet whether they lost their lives due to hostilities.[29][30]

Republic of Iceland (1944–)

Founding of the republic

On 31 December 1943, the Act of Union agreement expired after 25 years. Beginning on 20 May 1944, Icelanders voted in a four-day plebiscite on whether to terminate the personal union with the King of Denmark and establish a republic. The vote was 97% in favour of ending the union and 95% in favour of the new republican constitution.[31] Iceland became an independent republic on June 17, 1944, with Sveinn Björnsson as its first President. Denmark was still occupied by Germany. The Danish king, Christian X sent a message of congratulations to the Icelandic people.

Iceland had prospered during the course of the war, amassing considerable currency reserves in foreign banks. In addition to this, the country received the most Marshall Aid per capita of any European country in the immediate postwar years (at USD 209, with the war-ravaged Netherlands a distant second at USD 109).[32][33]

The new republican government, led by an unlikely three-party majority cabinet made up of conservatives (the Independence Party, Sjálfstæðisflokkurinn), social democrats (the Social Democratic Party, Alþýðuflokkurinn), and socialists (People's Unity Party – Socialist Party, Sósíalistaflokkurinn), decided to put the funds into a general renovation of the fishing fleet, the building of fish processing facilities, the construction of a cement and fertilizer factory, and a general modernization of agriculture. These actions were aimed at keeping Icelanders' standard of living as high as it had become during the prosperous war years.

The government's fiscal policy was strictly Keynesian, and their aim was to create the necessary industrial infrastructure for a prosperous developed country. It was considered essential to keep unemployment down to an absolute minimum and to protect the export fishing industry through currency manipulation and other means. Due to the country's dependence both on unreliable fish catches and foreign demand for fish products, Iceland's economy remained very unstable well into the 1990s, when the country's economy was greatly diversified.

NATO membership and the Cold War

In October 1946, the Icelandic and United States' governments agreed to terminate U.S. responsibility for the defense of Iceland, but the United States retained certain rights at Keflavík, such as the right to re-establish a military presence there, should war threaten.

Iceland became a charter member of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) on March 30, 1949, with the reservation that it would never take part in offensive action against another nation. The membership came amid an anti-NATO riot in Iceland. After the outbreak of the Korean War in 1950, and pursuant to the request of NATO military authorities, the United States and Alþingi agreed that the United States should again take responsibility for Iceland's defense.

This agreement, signed on May 5, 1951, was the authority for the controversial U.S. military presence in Iceland, which remained until 2006. The US base served as a hub for transports and communications to Europe, a key chain in the GIUK gap, a monitor of Soviet submarine activity, a linchpin in the early warning system for incoming Soviet attacks and interceptor of Soviet reconnaissance bombers.[34]

Although U.S. forces no longer maintain a military presence in Iceland, the U.S. still assumes responsibility over the country's defense through NATO. Iceland has retained strong ties to the other Nordic countries. As a consequence Norway, Denmark, Germany and other European nations have increased their defense and rescue cooperation with Iceland since the withdrawal of U.S. forces.

Cod Wars

The Cod Wars were a series of militarized interstate disputes between Iceland and the United Kingdom from the 1950s to the mid-1970s. The Proto Cod War (1952-1956) revolved around Iceland's extension of its fishery limits from 3 to 4 nautical miles. The First Cod War (1958-1961) was fought over Iceland's extension from 4 to 12 nautical miles (7 to 22 km). The Second Cod War (1972-1973) occurred when Iceland extended the limits to 50 miles (93 km). The Third Cod War (1975-1976) was fought over Iceland's extension of its fishery limits to 200 miles (370 km). Icelandic patrolships and British trawlers clashed in all four Cod Wars. The Royal Navy was sent to the contested waters in the last three Cod Wars, leading to highly publicized clashes.[35][36][37]

During these disputes, Iceland threatened closure of the U.S.-manned NATO base at Keflavík, and the withdrawal of its NATO membership. Due to Iceland's strategic importance during the Cold War, it was important for the US and NATO to maintain the base on Icelandic soil and to keep Iceland as a member of NATO. While the Icelandic government did go through on its threat to break off diplomatic relations with the UK during the Third Cod War, it never went through on its threats to close the US base to withdraw from NATO.[35][36][37]

It is rare for militarized interstate disputes of this magnitude and intensity to occur between two democracies with as close economic, cultural and institutional ties as Iceland and the UK.[37]

EEA membership and economic reform

In 1991, the Independence Party, led by Davíð Oddsson, formed a coalition government with the Social Democrats. This government set in motion market liberalisation policies, privatising a number of state-owned companies. Iceland then became a member of the European Economic Area in 1994. Economic stability increased and previously chronic inflation was drastically reduced.

In 1995, the Independence Party formed a coalition government with the Progressive Party. This government continued with free market policies, privatising two commercial banks and the state-owned telecom Landssíminn.

Corporate income tax was reduced to 18% (from around 50% at the beginning of the decade), inheritance tax was greatly reduced and the net wealth tax was abolished. A system of individual transferable quotas in the Icelandic fisheries, first introduced in the late 1970s, was further developed.

The coalition government remained in power through elections in 1999 and 2003. In 2004, Davíð Oddsson stepped down as Prime Minister after 13 years in office. Halldór Ásgrímsson, leader of the Progressive Party, took over as Prime Minister from 2004 to 2006, followed by Geir H. Haarde, Davíð Oddsson’s successor as leader of the Independence Party.

Following a recession in the early 1990s, economic growth was considerable, averaging about 4% per year from 1994. The governments of the 1990s and 2000s adhered to a staunch but domestically controversial pro-U.S. foreign policy, lending nominal support to the NATO action in the Kosovo War and signing up as a member of the Coalition of the willing during the 2003 invasion of Iraq.

In March 2006, the United States announced that it intended to withdraw the greater part of the Icelandic Defence Force. On 12 August 2006, the last four F-15s left Icelandic airspace. The United States closed the Keflavík Air Base in September 2006.

Following elections in May 2007, the Independence Party headed by Geir H. Haarde remained in government, albeit in a new coalition with the Social Democratic Alliance.

Financial crisis

In October 2008, the Icelandic banking system collapsed, prompting Iceland to seek large loans from the International Monetary Fund and friendly countries. Widespread protests in late 2008 and early 2009 resulted in the resignation of the government of Geir Haarde, which was replaced on 1 February 2009 by a coalition government led by the Social Democratic Alliance and the Left-Green Movement. Social Democrat minister Jóhanna Sigurðardóttir was appointed Prime Minister, becoming the world's first openly homosexual head of government of the modern era.[38][39] Elections took place in April 2009 and a continuing coalition government consisting of the Social Democrats and the Left-Green Movement was established in early May 2009.

The crisis resulted in the greatest migration from Iceland since 1887, with a net emigration of 5,000 people in 2009.[40] Iceland's economy stabilized under the government of Jóhanna Sigurðardóttir, and grew by 1.6% in 2012[41][42] but many Icelanders remained unhappy with the state of the economy and government austerity policies; the centre-right Independence Party was returned to power, in coalition with the Progressive Party, in the 2013 elections.

Historiography

Division of history into named periods

While it is convenient to divide history into named periods, it is also misleading because the course of human events neither starts or ends abruptly in most cases, and movements and influences often overlap. One period, as Gunnar Karlsson describes, can be considered the period from 930 CE to 1262–4 when there was no central government or leader, political power being characterised by chieftains ("goðar"). This period is referred to therefore as the þjóðveldisöld or goðaveldisöld (National or Chieftain State) period by Icelandic authors, and the Old Commonwealth or Freestate by English ones.

There is little consensus on how to divide Icelandic history. Gunnar's own book A Brief History of Iceland (2010) has 33 chapters with considerable overlap in dates. Jón J. Aðils' 1915 text, Íslandssaga (A History of Iceland) uses ten periods:

- Landnámsöld (Settlement Age) c. 870–930

- Söguöld (Saga Age) 930–1030

- Íslenska kirkjan í elstu tíð (The early Icelandic church) 1030–1152

- Sturlungaöld (Sturlung Age) 1152–1262

- Ísland undir stjórn Noregskonunga og uppgangur kennimanna (Norwegian royal rule and the rise of the clergy) 1262–1400

- Kirkjuvald (Ecclesiastical power) 1400–1550

- Konungsvald (Royal authority) 1550–1683

- Einveldi og einokun (Absolutism and monopoly trading) 1683–1800

- Viðreisnarbarátta (Campaign for restoration) [of past glories] 1801–1874

- Framsókn (Progress) 1875–1915

In another of Gunnar's books, Iceland's 1100 Years (2000), Icelandic history is divided into four periods:

- Colonisation and Commonwealth c. 870–1262

- Under foreign rule 1262 – c. 1800

- A primitive society builds a state 1809–1918

- The great 20th-century transformation

based mainly on forms of government, except for the last which reflects mechanisation of the fishing industry.[43]

See also

- Military history of Iceland

- Politics of Iceland

- President of Iceland

- Prime Minister of Iceland

- Timeline of Icelandic history

-

History of Iceland and some other articles, linked directly or indirectly – Wikipedia book

History of Iceland and some other articles, linked directly or indirectly – Wikipedia book

References

- ↑ "Jürgen Schieber, University of Indiana. G105 (Earth: Our Habitable Planet) Chapter 13: Evolution of Continents and Oceans". Retrieved 30 September 2014.

- ↑ "Fróðskaparsetur Føroya: Megindeildin fyri náttúruvísindi og heilsuvísindi. Uppskriftir og myndir frá jarðfrøði-ferðum kring landið (October 2004)". Archived from the original on 2007-08-13. Retrieved 30 September 2014.

- ↑ Carine, Mark; Schaefer, Hanno (2010). "The Azores diversity enigma: why are there so few Azorean endemic flowering plants and why are they so widespread?". Journal of Biogeography. 37 (1): 77–89. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2699.2009.02181.x.

- ↑ "US Geological Survey. Mauna Loa: Earth's Largest Volcano". Retrieved 30 September 2014.

- ↑ Björn Þorsteinsson og Bergsteinn Jónsson (1991). Íslands Saga: til okkar daga. Sögufélagið. ISBN 9979-9064-4-8., page 11

- ↑ Eldjám, Kristján (1949). "Fund af romerske mønter på Island". Nordisk Numismatisk Årsskrift: 4–7.

- ↑ The 9th-century Irish monk and geographer Dicuil describes Iceland in his work Liber de Mensura Orbis Terrae.

- ↑ New View on the Origin of First Settlers in Iceland, Iceland Review Online, 4 June 2011, accessed 16 June 2011.

- ↑ Vésteinsson, Orri; Gestsdóttir, Hildur (2014-11-01). "The Colonization of Iceland in Light of Isotope Analyses". Journal of the North Atlantic: 137–145. doi:10.3721/037.002.sp709.

- 1 2 Information about Icelandic diet & history thereof Archived February 20, 2012, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑

- ↑ Solrun B. Jensdottir Hardarson, "The 'Republic of Iceland' 1940–44: Anglo-American Attitudes and Influences," Journal of Contemporary History (1974) 9#4 pp. 27–56 in JSTOR

- 1 2 Bjarnason, Gunnar Þór (2015). Þegar siðmenningin fór til fjandans. Íslendingar og stríðið mikla 1914-1918. p. 16.

- 1 2 Jónsson, Guðmundur (1999). Hagvöxtur og iðnvæðing. Þjóðarframleiðsla á Íslandi 1870–1945.

- ↑ Bjarnason, Gunnar Þór (2015). Þegar siðmenningin fór til fjandans. Íslendingar og stríðið mikla 1914-1918. pp. Ch. 12.

- ↑ Bjarnason, Gunnar Þór (2015). Þegar siðmenningin fór til fjandans. Íslendingar og stríðið mikla 1914-1918. p. 148.

- 1 2 3 Jensdóttir, Sólrún (1980). Ísland á bresku valdssvæði 1914-1918.

- ↑ Thorhallsson, Baldur; Joensen, Tómas (2015-12-15). "Iceland's External Affairs from the Napoleonic Era to the occupation of Denmark: Danish and British Shelter". Icelandic Review of Politics & Administration. 11 (2): 187–206. ISSN 1670-679X.

- ↑ Bjarnason, Gunnar Þór (2015). Þegar siðmenningin fór til fjandans. Íslendingar og stríðið mikla 1914-1918. pp. 173–175.

- ↑ Bjarnason, Gunnar Þór (2015). Þegar siðmenningin fór til fjandans. Íslendingar og stríðið mikla 1914-1918. pp. 236–238, 288–289.

- 1 2 Bjarnason, Gunnar Þór (2015). Þegar siðmenningin fór til fjandans. Íslendingar og stríðið mikla 1914-1918. p. 15.

- ↑ Karlsson, Gunnar (2000). History of Iceland. pp. 283–284.

- ↑ Bjarnason, Gunnar Þór (2015). Þegar siðmenningin fór til fjandans. Íslendingar og stríðið mikla 1914-1918. pp. 141–142.

- 1 2 3 Karlsson, Gunnar (2000). History of Iceland. pp. 308–312.

- ↑ Hardarson, (1974) p 29-31

- 1 2 3 Karlsson, Gunnar (2000). History of Iceland. p. 314.

- ↑ Hardarson, (1974) pp 32–33

- ↑ Hardarson, (1974) pp 43–45

- 1 2 3 "Hve margir Íslendingar dóu í seinni heimsstyrjöldinni?". Vísindavefurinn. Retrieved 2016-02-27.

- 1 2 Karlsson, Gunnar (2000). History of Iceland. p. 316.

- ↑ Hardarson, (1974) p 56

- ↑ "Vísindavefurinn: Hversu há var Marshallaðstoðin sem Ísland fékk eftir seinni heimsstyrjöld?". Vísindavefurinn. Retrieved 30 September 2014.

- ↑ Margrit Müller, Pathbreakers: Small European Countries Responding to Globalisation and, , p. 385

- ↑ "Return to Keflavik Station". Foreign Affairs. Retrieved 2016-02-25.

- 1 2 "Now, the Cod Peace", Time, June 14, 1976. p. 37

- 1 2 GuÐmundsson, GuÐmundur J. (2006-06-01). "The Cod and the Cold War". Scandinavian Journal of History. 31 (2): 97–118. doi:10.1080/03468750600604184. ISSN 0346-8755.

- 1 2 3 Steinsson, Sverrir (2016-03-22). "The Cod Wars: a re-analysis". European Security. 0 (0): 1–20. doi:10.1080/09662839.2016.1160376. ISSN 0966-2839.

- ↑ Moody, Jonas (2009-01-30). "Iceland Picks the World's First Openly Homosexual PM". Time. Retrieved 2009-01-31.

- ↑ "First gay PM for Iceland cabinet". BBC News. 1 February 2009. Retrieved 2009-02-01.

- ↑ "Iceland lost almost 5000 people in 2009" (PDF). Retrieved 2012-01-08.

- ↑ "Statistics Iceland – News » News". Statice.is. Retrieved 2012-09-22.

- ↑ Jolly, David (2010-12-07). "Iceland Recession Ends as Economy Returns to Growth". Iceland;Ireland;Greece: NYTimes.com. Retrieved 2012-11-17.

- ↑ "Gunnar Karlsson. "How and why is the history of Iceland divided into periods?". The Icelandic Web of Science 5.3.2005.". The Icelandic Web of Science. Retrieved 30 September 2014.

Bibliography

- Axel Kristinsson. "Is there any tangible proof that there were Irish monks in Iceland before the time of the Viking settlements?" (2005) in English in Icelandic

- Bergsteinn Jónsson and Björn Þorsteinsson. "Íslandssaga til okkar daga" Sögufélag. Reykjavík. (1991) (in Icelandic) ISBN 9979-9064-4-8

- Byock, Jesse. Medieval Iceland: Society, Sagas and Power University of California Press (1988) ISBN 0-520-06954-4 ISBN 0-226-52680-1

- Guðmundur Hálfdanarson;"Starfsmaður | Háskóli Íslands". Hug.hi.is. Retrieved 2010-01-31. "Historical Dictionary of Iceland" Scarecrow Press. Maryland, USA. (1997) ISBN 0-8108-3352-2

- Gunnar Karlsson. "History of Iceland" Univ. of Minneapolis. (2000) ISBN 0-8166-3588-9 "The History of Iceland (Gunnar Karlsson) – book review". Dannyreviews.com. Retrieved 2010-01-31.

- Gunnar Karlsson. "Iceland's 1100 Years: History of a Marginal Society". Hurst. London. (2000) ISBN 1-85065-420-4.

- Gunnar Karlsson. "A Brief History of Iceland". Forlagið 2000. 2nd ed. 2010. Trans. Anna Yates. ISBN 978-9979-3-3164-3

- Helgi Skúli Kjartansson; "Helgi Skúli Kjartansson". Starfsfolk.khi.is. 2004-09-26. Retrieved 2010-01-31. "Ísland á 20. öld". Reykjavík. (2002) ISBN 9979-9059-7-2

- Sverrir Jakobsson. ‘The Process of State-Formation in Medieval Iceland’, Viator. Journal of Medieval and Renaissance Studies 40:2 (Autumn 2009), 151–70.

- Sverrir Jakobsson. The Territorialization of Power in the Icelandic Commonwealth, in Statsutvikling i Skandinavia i middelalderen, eds. Sverre Bagge, Michael H. Gelting, Frode Hervik, Thomas Lindkvist & Bjørn Poulsen (Oslo 2012), 101–18.

- Jón R. Hjálmarsson (2009). History of Iceland: From the Settlement to the Present Day. Reykjavik: Forlagið Publishing. ISBN 978-9979-53-513-3.

- Sigurður Gylfi Magnússon. Wasteland with Words. A Social History of Iceland (London: Reaktion Books, 2010)

- Miller, William Ian; "University of Michigan Law School Faculty & Staff". Cgi2.www.law.umich.edu. 1996-10-24. Retrieved 2010-01-31. Bloodtaking and Peacemaking: Feud, Law, and Society in Saga Iceland. University Of Chicago Press (1997) ISBN 0-226-52680-1

External links

- History of Iceland from the Icelandic embassy in Japan

- U.S. Government text public domain

- History of Iceland: Primary Documents