Mayon Volcano

| Mayon Volcano | |

|---|---|

| Bulkang Mayon (Central Bikol) | |

| |

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 2,463 m (8,081 ft) [1] |

| Prominence | 2,447 m (8,028 ft) [1] |

| Listing | |

| Coordinates | 13°15′24″N 123°41′6″E / 13.25667°N 123.68500°ECoordinates: 13°15′24″N 123°41′6″E / 13.25667°N 123.68500°E |

| Geography | |

.svg.png) Mayon Volcano Location within the Philippines | |

| Location | Luzon |

| Country | Philippines |

| Region | Bicol Region |

| Province | Albay |

| Cities and municipalities | |

| Geology | |

| Age of rock | more than 20 million years old |

| Mountain type | Stratovolcano |

| Last eruption | September 18, 2014 |

| Climbing | |

| First ascent | Scotsmen Paton & Stewart (1858)[2] |

Mayon Volcano (Central Bikol: Bulkan Mayon, Filipino: Bulkang Mayon), also known as Mount Mayon or simply Mayon, is an active stratovolcano in the province of Albay in Bicol Region, on the island of Luzon in the Philippines. Renowned as the "perfect cone" because of its symmetric conical shape, the volcano and its surrounding landscape was declared a national park on July 20, 1938, the first in the nation. It was reclassified a Natural Park and renamed Mayon Volcano Natural Park in the year 2000.[3] Local folklore refers to the volcano being named after the legendary princess-heroine Daragang Magayon (English: Beautiful Lady).[4]

Location

Mayon Volcano is the main landmark and highest point of the province of Albay and the whole Bicol Region in the Philippines, rising 2,462 metres (8,077 ft) from the shores of the Albay Gulf about 10 kilometres (6.2 mi) away.[5][6] The volcano is geographically shared by the eight cities and municipalities of Legazpi, Daraga, Camalig, Guinobatan, Ligao, Tabaco, Malilipot and Santo Domingo (clockwise from Legazpi), which divide the cone like slices of a pie when viewed from above.

Geomorphology

Mayon is a classic stratovolcano with a small central summit crater. The cone is considered the world's most perfectly formed volcano for its symmetry,[6] which was formed through layers of lava flows and pyroclastic surges from past eruptions and erosion. The upper slopes of the basaltic-andesitic stratovolcano are steep, averaging 35–40 degrees.

Like other volcanoes located around the Pacific Ocean, Mayon is a part of the Pacific Ring of Fire. It is located on the southeastern side of Luzon, close to the Philippine Trench which is the convergent boundary, where the Philippine Sea Plate is driven under the Philippine Mobile Belt. When a continental plate meets an oceanic plate, the lighter and thicker continental material overrides the thinner and heavier oceanic plate, forcing it down into the Earth's mantle and melting it. Superheated magma and gases may be forced through weaknesses in the continental crust caused by the subduction of the oceanic plate, and one such exit point is Mayon.

Recorded eruptions

Mayon is the most active volcano in the Philippines, erupting over 49 times in the past 400 years.[7] The first record of a major eruption was witnessed in February 1616 by Dutch explorer Joris van Spilbergen who recorded it on his log in his circumnavigation trip around the world.[8] The first eruption for which an extended account exists was the six-day event of July 20, 1766.[9][10]

1814 eruption

The most destructive eruption of Mayon occurred on February 1, 1814 (VEI=4).[10] Lava flowed but less than the 1766 eruption. The volcano belched dark ash and eventually bombarded the town of Cagsawa with tephra that buried it. Trees burned, rivers were certainly damaged. Proximate areas were also devastated by the eruption, with ash accumulating to 9 m (30 ft) in depth. In Albay, 2,200 locals perished in what is considered to be the most lethal eruption in Mayon's history;[6] though estimates by PHIVOLCS list the casualties at about 1,200. The eruption is believed to have contributed to the accumulation of atmospheric ash capped by the catastrophic 1815 eruption of Mount Tambora, that led to the Year Without a Summer in 1816.

1881–1882 eruption

From July 6, 1881 until approximately August 1882,[10] Mayon underwent a strong (VEI=3) eruption. Samuel Kneeland, a naturalist, professor and geologist, personally observed the volcanic activity on Christmas Day, 1881, about five months after the start of the activity:

At the date of my visit, the volcano had poured out, for five months continuously, a stream of lava on the Legaspi side from the very summit. The viscid mass bubbled quietly but grandly, and overran the border of the crater, descending several hundred feet in a glowing wave, like red-hot iron. Gradually, fading as the upper surface cooled, it changed to a thousand sparkling rills among the crevices, and, as it passed beyond the line of complete vision behind the woods near the base, the fires twinkled like stars, or the scintillions of a dying conflagration. More than half of the mountain height was thus illuminated.[11]

1897 eruption

Mayon Volcano's longest uninterrupted eruption occurred on June 23, 1897 (VEI=4), which lasted for seven days of raining fire. Lava once again flowed down to civilization. Eleven kilometers (7 miles) eastward, the village of Bacacay was buried 15 m (49 ft) beneath the lava. In Libon 100 people were killed by steam and falling debris or hot rocks. Other villages like San Roque, Misericordia and Santo Niño became deathtraps. Ash was carried in black clouds as far as 160 kilometres (99 mi) from the catastrophic event, which killed more than 400 people.[6]

1984 and 1993 eruptions

No casualties were recorded from the 1984 eruption after more than 73,000 people were evacuated from the danger zones as recommended by PHIVOLCS scientists.[12] But in 1993, pyroclastic flows killed 75 people, mainly farmers, during the eruption.[13]

2006 eruptions

Mayon's 48th modern-era eruption was on July 13, 2006, followed by quiet effusion of lava that started on July 14, 2006.[10][14] Nearly 40,000 people were evacuated from the 8-kilometre (5.0 mi) danger zone on the southeast flank of the volcano.

After an ash explosion of September 1, 2006, a general decline in the overall activity of Mayon Volcano was established. The decrease in key parameters such as seismicity, sulfur dioxide emission rates and ground inflation all indicated a waning condition. The slowdown in the eruptive activity was also evident from the decrease in intensity of crater glow and the diminishing volume of lava extruded from the summit. PHILVOLCS Alert Level 4 was lowered to Level 3 on September 11, 2006; to Level 2 on October 3, 2006; and to Level 1 on October 25, 2006.[15]

2008 eruption

On August 10, 2008, a small summit explosion ejected ash 200 metres (660 ft) above the summit, which drifted east-northeast. In the weeks prior to the eruption,[10] a visible glow increased within the crater and increased seismicity.[16]

2009–2010 eruption

On July 10, 2009, PHIVOLCS raised the status from Alert Level 1 (low level unrest) to Alert Level 2 (moderate unrest) because the number of recorded low frequency volcanic earthquakes rose to the same level as those prior to the 2008 phreatic explosion.[17][18]

At 5:32 a.m. on October 28, 2009, a minor ash explosion lasting for about one minute occurred in the summit crater. A brown ash column rose about 600 metres (2,000 ft) above the crater and drifted northeast. In the prior 24 hours, 13 volcanic earthquakes were recorded. Steam emission was at moderate level, creeping downslope toward the southwest. PHIVOLCS maintained the Alert Status at Level 2, but later warned that with the approach of tropical cyclone international codename Mirinae, the danger of lahars and possible crater wall collapse would greatly increase and all specified precautions should be taken.[19]

At 1:58 am on November 11, 2009, a minor ash explosion occurred at the summit crater lasting for about three minutes. This was recorded by the seismic network as an explosion-type earthquake with rumbling sounds. Incandescent rock fragments at the upper slope were observed in nearby barangays. Ash column was not observed because of cloud cover. After dawn, field investigation showed ashfall had drifted southwest of the volcano. In the 24-hour period, the seismic network recorded 20 volcanic earthquakes. Alert Status was kept at Level 2 indicating the current state of unrest could lead to more ash explosion or eventually to hazardous magmatic eruption.[20]

At 8 pm on December 14, 2009, after 83 volcanic quakes in the preceding 24 hours[21] and increased sulfur dioxide emissions, PHIVOLCS raised the Alert status to Level 3.[22]

Early in the morning of December 15, 2009, a moderate ash explosion occurred at the summit crater and "quiet extrusion of lava" resulted in flows down to about 500 metres (1,600 ft) from the summit.[23] By evening, Albay Province authorities evacuated about 20,000 residents out of the 8-kilometre (5.0 mi) danger zone and into local evacuation centres. About 50,000 people live within the 8-kilometre (5.0 mi) zone.[24][25]

On December 17, 2009, five ash ejections occurred, with one reaching 500 metres (1,600 ft) above the summit. Sulfur dioxide emission increased to 2,758 tonnes per 24 hours, lava flows reached down to 1,500 metres (4,900 ft) below the summit, and incandescent fragments from the lava pile continuously rolling down Bonga Gully reached a distance of 3–4 km below the summit. By midday, a total of 33,833 people from 7,103 families had been evacuated, 72 percent of the total number of people that needed to be evacuated, according to Albay Governor Joey Salceda.[26]

On December 20, 2009, PHIVOLCS raised Mayon's status level to alert level 4 because of an increasing lava flow in the southern portion of the volcano and an increase in sulfur dioxide emission to 750 tonnes per day. Almost 460 earthquakes in the volcano were monitored. In the border of the danger zone, rumbling sounds like thunder were heard. Over 9,000 families (44,394 people) were evacuated by the Philippine government from the base of the volcano.[27] No civilian was permitted within the 8 km danger zone, which was cordoned off by the Philippine military who actively patrolled to enforce the "no-go" rule and to ensure no damage or loss of property of those evacuated.[28]

Alert level 4 was maintained as the volcano remained restive through the month of December, prompting affected residents to spend Christmas and the New Year in evacuation centers.[29] On December 25, sulfur dioxide emissions peaked at 8,993 tons per day.[30][31] On December 28, PHIVOLCS director Renato Solidum commented on the status of the volcano, "You might think it is taking a break but the volcano is still swelling."[28] On the next day December 29, a civil aviation warning for the airspace near the summit was included in the volcano bulletins.[32] The ejected volcanic material since the start of the eruption was estimated to have been between 20 million to 23 million cubic meters of rocks and volcanic debris, compared to 50 million to 60 million cubic meters in past eruptions.[33]

On January 2, 2010, PHIVOLCS lowered the alert level of the volcano from level 4 to level 3, citing decreasing activity observed over the prior four days.[34] The state agency noted the absence of ash ejections and relative weakness of steam emissions and the gradual decrease in sulfur dioxide emissions from a maximum of 8,993 tonnes per day to 2,621 tonnes per day.[31] 7,218 families within the 7–8 km danger zones returned to their homes, while 2,728 families residing in the 4–6 km danger zone remained in the evacuation centers pending a decision to further lower the alert level.[35]

On January 13, 2010, PHIVOLCS reduced the Alert Level from 3 to 2 due to a further reduction in the likelihood of hazardous eruption.[36]

Government response

Albay governor Joey Salceda declared the disaster zone an 'open city' area to encourage aid from external groups. Potential donors of relief goods were not required to secure clearance from the Provincial Disaster Coordinating Council, and were coordinated directly with support groups at the local government level.[37]

The restiveness of the volcano also stimulated the tourism industry of the province. Up to 2,400 tourists per day arrived in the area in the two weeks after the volcano started erupting on December 14, filling local hotels, compared to a more modest average of 200 in the days prior. However it was reported that some tourists lured by local "guides" ignored government warnings not to venture into the 8-kilometre (5.0 mi) danger zone. "It's a big problem. I think the first violation of the zero casualty (record) will be a dead tourist," said Salceda.[38]

Speaking about thrill-seekers finding their way into the area, Salceda warned, "At the moment of the eruption, the local guides will have better chance of getting out. The helpless tourist will be left behind." [38]

International response

Following the declaration of alert level 3 for the volcano, the United States issued an advisory cautioning its nationals from traveling to Mayon. Canada and the United Kingdom also posted advisories discouraging their nationals from visiting the volcano.[39]

The United States government committed $100,000 in financial aid for the evacuees of Mayon Volcano. In cooperation with the Philippine government the assistance was delivered through the Philippine National Red Cross and other NGOs by USAID.[40]

The Albay provincial government ordered the local military to add more checkpoints, place roadblocks and arrest tourists caught traveling inside the 8-kilometre (5.0 mi) danger zone.[41]

Power and water supply were cut off within the danger zone to further discourage residents from returning. The Commission on Human Rights allowed the use of emergency measures and gave the authorities clearance to forcibly evacuate residents who refused to leave.[42]

When the alert level around the volcano was lowered from alert level 4 to alert level 3 on January 2, 2010, the Albay provincial government ordered a decampment of some 47,000 displaced residents from the evacuation centers.[43] Power and water supply in the danger zones were restored.[29] Military vehicles were used to transport the evacuees back to their homes, while food supplies and temporary employment through the Department of Social Welfare and Development (DSWD) were provided to the heads of each family.[43][44] As of January 3, 2010, the National Disaster Coordinating Council reported the overall cost of humanitarian aid and other assistance provided by the government and non-government organizations (NGOs) has reached over 61 million pesos since the start of the eruption.[45]

The United Nations World Food Programme (UN-WFP) delivered 20 tons of high energy biscuits to the evacuees to complement supplies provided by the DSWD, with more allocated from emergency food stocks intended for relief from the effects of the 2009 Pacific typhoon season.[46] When the alert level was downgraded to level 3 on January 2, 2010, UN-WFP provided three days worth of food for evacuees returning to their homes who will continue to receive supplies already set aside for them.[34]

2013 phreatic eruption

On May 7, 2013, at 8 a.m. (PST), the volcano produced a surprise phreatic eruption lasting 73 seconds. Ash, steam and rock were produced during this eruption. Ash clouds reached 500 meters above the volcano's summit and drifted west southwest.[47] The event killed five climbers, of whom three were German, one was a Spaniard living in Germany,[48][49] and one was a Filipino tour guide. Seven others were reported injured.[50][51] The bodies of the hikers were soon located by the authorities.[52] However, due to rugged and slippery terrain, the hikers' remains were slowly transferred from Camp 2 to Camp 1, the site of the rescue operations at the foot of the volcano. According to Dr. Butch Rivera of Bicol Regional Training and Teaching Hospital, the hikers died due to trauma in their bodies, and suffocation.[53] Authorities were also able to rescue a Thai national who was unable to walk due to fatigue and had suffered a broken arm and burns on the neck and back.[54]

Despite the eruption, the Philippine Institute of Volcanology and Seismology stated that the alert level would remain at 0.[51] No volcanic earthquake activity was detected in the 24 hours prior to the eruption, and no indication of further intensification of volcanic activity was observed.[55] and no evacuation was being planned.[56]

International response

The government of the United Kingdom advised its nationals to follow the advisories given by the local authorities, and respect the 6 km permanent danger zone.[57] The advisory was given a day after the May 7, 2013 phreatic explosion.[58]

2014 renewed activity

On August 12, 2014, a new 30m-50m high lava dome appeared in the summit crater. This event was preceded by inflations of the volcano (measured by precise leveling, tilt data, and GPS), and increases in sulphur dioxide gas emissions.[59]

On September 14, 2014, rockfall events at the southeastern rim of the crater and heightened seismic activity caused PHIVOLCS to increase the alert level for Mayon from 2 to 3, which indicates relatively high unrest with magma at the crater, and that hazardous eruption is possible within weeks.[60] The rockfalls and visible incandescence of the crater from molten lava and hot volcanic gas both indicated a possible incipient breaching of the growing summit lava dome.

On September 15, 2014, NASA's Moderate-Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) detected thermal anomalies near Mayon's summit, consistent with magma at the surface.[61]

On September 16, 2014, provincial governor Joey Salceda said that the government would begin to "fast-track the preparation to evacuate 12,000 families in the 6-8 km extended danger zone", and soldiers would enforce the no-go areas.[62]

On September 18, 2014, PHIVOLCS reported 142 VT earthquake events and 251 rockfall events. White steam plumes drifted to the south-southwest and rain clouds covered the summit. Sulfur dioxide (SO2) emission was measured at an 757 tonnes after a peak of 2,360 tonnes on September 6. Ground deformation (precise leveling and tilt meters) during the 3rd week of August 2014 recorded edifice inflation.[63]

Deadly lahars

Following the eruption of November 30, 2006, strong rainfall which accompanied Typhoon Durian produced lahars from the volcanic ash and boulders of the last eruption killing at least 1,266 people. The precise figure may never be known since many people were buried under the mudslides.[4] A large portion of the village of Padang (an outer suburb of Legazpi City) was covered in mud up to the houses' roofs.[64][65] Students from Aquinas University in Barangay Rawis, also in Legazpi, were among those killed as mudslides engulfed their dormitory. Central Legazpi escaped the mudslide but suffered from severe flooding and power cuts.

Parts of the town of Daraga were also devastated, including the Cagsawa area, where the ruins from the eruption of 1814 were partially buried once again. Large areas of Guinobatan, Albay were destroyed, particularly Barangay Maipon.

Similar post-eruption lahar occurred in October 1766, months after the July eruption of that year. The heavy rainfall also accompanying a violent typhoon carried down disintegrated fragmental ejecta, burying plantations and whole villages. In 1825, the event was repeated in Cagsawa killing 1,500 people.[66]

Monitoring Mayon

Mayon Volcano is the most active volcano in the Philippines, and its activity is regularly monitored by PHIVOLCS from their provincial headquarters on Ligñon Hill, about 12 kilometres (7.5 mi) SSE from the summit.[14]

Three telemetric units are installed on Mayon's slopes, which send information to the seven seismometers in different locations around the volcano. These instruments relay data to the Ligñon Hill observatory and the PHIVOLCS central headquarters on the University of the Philippines Diliman campus.

PHIVOLCS also deploys electronic distance meters (EDMs), precise leveling benchmarks, and portable fly spectrometers to monitor the volcano's daily activity.[67][68]

Sept 12, 2016 The Philippine Institute of Volcanology and Seismology (Phivolcs) has warned of a possible "big" Mayon volcano eruption in the coming days. [69]

Gallery

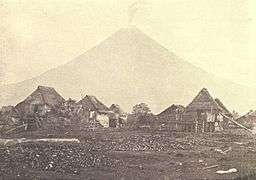

Mayon in 1899.

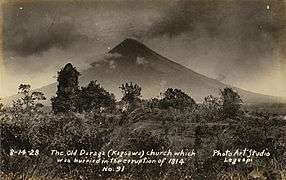

Mayon in 1899. Cagsawa ruins in 1928, with parts of its facade still intact.

Cagsawa ruins in 1928, with parts of its facade still intact.- Mayon with the Cagsawa ruins.

- View from Daraga.

The volcano from a viewdeck in Ligñon Hill.

The volcano from a viewdeck in Ligñon Hill. Mayon Volcano as of 2010

Mayon Volcano as of 2010 View from Camalig.

View from Camalig. Another view of Mayon in 2010

Another view of Mayon in 2010 Mayon summit.

Mayon summit..jpg)

Mayon Volcano and Legazpi City at night

Mayon Volcano and Legazpi City at night- USNS Mercy (T-AH-19) anchored off Mayon volcano in July 2016

See also

- Cagsawa Ruins

- List of volcanoes in the Philippines

- List of volcanic eruptions by death toll

- List of protected areas of the Philippines

- List of Southeast Asian mountains

- List of mountains in the Philippines

- Geography of the Philippines

References

- 1 2 de Ferranti, Jonathan; Aaron Maizlish. "Philippine Mountains – 29 Mountain Summits with Prominence of 1,500 meters or greater". Retrieved 2011-01-31.

- ↑ "Encyclopedia Britanica, Vol. 18, 9th Ed.", pg. 749. Henry G. Allen & Company, New York.

- ↑ "Protected Areas in Region 5" Archived December 19, 2013, at the Wayback Machine.. Protected Areas and Wildlife Bureau. Retrieved on 2011-10-15.

- 1 2 England, Vaudine (2009-12-24). "Mount Mayon: a tale of love and destruction". BBC News. Retrieved 2009-12-25.

- ↑ "Mayon Volcano, Philippines". Philippines Department of Tourism. Volcano.und.edu. Archived from the original on 2007-10-12. Retrieved 2007-11-20.

- 1 2 3 4 David, Lee (2008). "Natural Disasters", pp. 416-417. Infobase Publishing.

- ↑ "Chronology of Historical Eruptions of Mayon Volcano". Philippine Institute of Volcanology and Seismology. Retrieved on 2012-01-03.

- ↑ Bankoff, Greg (2003). "Culture of disasters: society and natural hazards in the Philippines", pg. 39. RoutlegeCurzon, New York. ISBN 0-203-22189-3.

- ↑ Ocampo, Ambeth R. (2013-05-06). "The Mayon eruption of 1814". Inquirer Opinion. Retrieved on 2013-05-07.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Mayon - Eruptive History". Global Volcanism Program. Retrieved on 2015-03-05.

- ↑ Samuel Kneeland (1888). Volcanoes and earthquakes. D. Lothrop Co. p. 116.

- ↑ "USGS". Retrieved 2008-06-25.

- ↑ "'Ominous quiet' at Mayon volcano". BBC. 2006-08-10. Retrieved 2013-05-12.

- 1 2 "Mayon Volcano". Philippine Institute of Volcanology and Seismology. Archived from the original on December 2, 2008. Retrieved 2009-12-14.

- ↑ "Mayon Volcano Bulletin 10/25/2006". Archived from the original on 2008-04-20. Retrieved 2008-05-06.

- ↑ "Mayon Volcano Advisory". Philippine Institute of Volcanology and Seismology. 2008-08-10. Retrieved 2009-12-24.

- ↑ "Mayon Volcano Bulletin". Philippine Institute of Volcanology and Seismology (via Google cache). 2009-07-10. Retrieved 2009-12-31.

- ↑ "Mayon in 'state of unrest,' alert level raised". ABS-CBN News. 2009-07-10. Retrieved 2010-01-01.

- ↑ "Mayon spews ash anew". Volcano Monitor. Philippine Daily Inquirer. October 28, 2009. Retrieved 2009-12-05.

- ↑ "Mayon Volcano Advisory (November 2009)". Philippine Institute of Volcanology and Seismology. 2009-11-11. Retrieved 2009-12-11.

- ↑ Papa, Alcuin (2009-12-15). "6–7 km from Mayon volcano off limits to people". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Retrieved 2009-12-15.

- ↑ "Lava flows from Mayon Volcano". ABS-CBN News. 2009-12-15. Retrieved 2009-12-24.

- ↑ "Mayon Volcano Bulletin 3". Philippine Institute of Volcanology and Seismology. 16 December 2009. Archived from the original on July 6, 2015. Retrieved 17 November 2015.

- ↑ Associated Press (15 December 2009). "20,000 Evacuated as Philippine Volcano Oozes Lava". Fox News. Retrieved 7 June 2013.

- ↑ "Residents flee as Philippines volcano threatens to erupt". CNN World. 2009-12-15. Retrieved 2009-12-24.

- ↑ "Volcano Monitor – PHIVOLCS warns: Mayon to blow its top in a few weeks". Philippine Daily Inquirer. 2009-12-18. Retrieved 2009-12-18.

- ↑ "Volcano spews lava as eruption looms". CNN World. 2009-12-22. Retrieved 2009-12-24.

- 1 2 "Inquirer Volcano Monitor 2009-12-27". Philippine Daily Inquirer. 2009-12-27. Retrieved 2009-12-27.

- 1 2 Papa, Alcuin & Nasol, Rey M. (2010-01-01). "Mayon quieting down". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Retrieved 2010-01-02.

- ↑ "Mayon Volcano Bulletin 13". Philippine Institute of Volcanology and Seismology. 26 December 2009. Archived from the original on September 29, 2015. Retrieved 17 November 2015.

- 1 2 "Mayon Volcano Bulletin 20". Philippine Institute of Volcanology and Seismology. 2 January 2010. Archived from the original on September 29, 2015. Retrieved 17 November 2015.

- ↑ "Mayon Volcano Bulletin 16". Philippine Institute of Volcanology and Seismology. 29 December 2009. Archived from the original on September 29, 2015. Retrieved 17 November 2015.

- ↑ Flores, Helen (2010-01-02). "Phivolcs may lower Mayon alert level". The Philippine Star. Retrieved 2010-01-02.

- 1 2 Associated Press (2 January 2010). "Philippine volcano calming; thousands head home". The Hindu. Chennai, India. Retrieved 7 June 2013.

- ↑ "Alert level around Mayon lowered to 3". GMA News.TV. 2010-01-02. Retrieved 2010-01-02.

- ↑ "Mayon Volcano Bulletin 31". Philippine Institute of Volcanology and Seismology. 13 January 2010. Archived from the original on September 29, 2015. Retrieved 17 November 2015.

- ↑ MA Loterte (2009-12-28). "PGMA visits Mayon evacuees, assures government aid". Philippine Information Agency. Retrieved 2009-12-30.

- 1 2 "Thrill-seeking tourists flock to Philippine volcano". Agence France-Presse. 2009-12-30. Retrieved 2009-12-30.

- ↑ "UK, Canada to nationals: Stay away from Mayon Volcano". GMA News.TV. 2009-12-19. Retrieved 2010-01-02.

- ↑ Zhang Xiang (2009-12-30). "U.S. provides financial aid to Mayon Volcano evacuees". Xinhua News Agency. Retrieved 2009-12-30.

- ↑ "Authorities want 'hardheaded' Mayon tourists arrested". GMA News.TV. 2009-12-28. Retrieved 2009-12-30.

- ↑ Dedace, Sophia Regine (2009-12-31). "Albay govt to cut power in Mayon danger zones". GMA News.TV. Retrieved 2009-12-31.

- 1 2 Recuenco, Aaron B. (2010-01-02). "Worst is over at Mayon". Manila Bulletin. Retrieved 2010-01-02.

- ↑ Jerusalem, Evelyn E. "Mayon evacuees avails of the cash for work project". Department of Social Welfare and Development (Philippines). Retrieved 2010-01-02.

- ↑ Rabonza, Glenn J. (January 3, 2010). "NDCC Update Sitrep No. 22 re Mayon Volcano" (PDF). National Disaster Coordinating Council. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 4, 2011. Retrieved 2010-01-03.

- ↑ "UN-WFP sends aid for Mayon Volcano evacuees". Philippine Information Agency. 2009-12-29. Retrieved 2010-01-01.

- ↑ "MAYON VOLCANO ADVISORY 07 May 2013 8:30 AM". Philippine Institute of Volcanology and Seismology. May 7, 2013. Retrieved May 7, 2013.

- ↑ "Bodies of 4 Mayon volcano hikers arrive in Manila". InterAksyon.com.

- ↑ "Vulkanausbruch auf den Philippinen: Leichen deutscher Bergsteiger am Vulkan Mayon geborgen". stern.de.

- ↑ "Philippine volcano Mount Mayon in deadly eruption". BBC News Asia. May 7, 2013. Retrieved May 7, 2013.

- 1 2 Aaron B. Recuenco (May 7, 2013). "Death toll at Mayon rises to five, seven injured". Manila Bulletin. Retrieved May 7, 2013.

- ↑ "Bodies of 5 missing hikers spotted in Mayon Volcano". Interaksyon. May 8, 2013. Retrieved May 8, 2013.

- ↑ "Rescuers unable to bring down remains of 5 Mayon mountaineers". Philippines News Agency. Interaksyon. May 9, 2013. Retrieved May 9, 2013.

- ↑ "Last Thai survivor rescued from Mayon". Philippines News Agency. Interaksyon. May 8, 2013. Retrieved May 9, 2013.

- ↑ "5 dead, 7 hurt in Mayon Volcano ash eruption". The Philippine Star. May 7, 2013. Retrieved May 7, 2013.

- ↑ May 7, 2013 (May 6, 2013). "Mayon Volcano Erupts, Spewing Rocks And Ash And Killing 5 Climbers In Philippines". Associated Press. The Huffington Post. Retrieved May 7, 2013.

- ↑ "UK urged citizens to heed warnings on Mayon". Sun.Star. May 8, 2013. Retrieved May 9, 2013.

- ↑ "UK tells nationals in PHL to follow authorities' advice on Mayon". GMA News and Public Affairs. May 8, 2013. Retrieved May 9, 2013.

- ↑ PHIVOLCS Mayon volcano bulletin of Friday, 15 August 2014 06:49 local time. Retrieved September 15, 2014.

- ↑ PHIVOLCS Mayon volcano bulletin of Friday, 15 September 2014 14:02 local time. Retrieved September 15, 2014.

- ↑ MODVOLC detection of MODIS band 21 thermal pixels at Mayon's summit. Retrieved 19 September 2014.

- ↑ Reuters news article. Retrieved September 16, 2014.

- ↑ Mayon volcano bulletin of Friday, 18 August 2014 08:00 local time. Retrieved September 18, 2014.

- ↑ "Typhoon sends red-hot boulders into villages" – CNN.com (archived from the original on 2008-01-25).

- ↑ "Yahoo! News". Retrieved 2008-06-25.

- ↑ Maso, Saderra (1902). "Seismic and Volcanic Centers of the Philippine Archipelago", pp.13–14. Bureau of Public Printing, Manila.

- ↑ Nasol, Rey M. (2009-12-27). "Mayon instruments intact despite eruption". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Retrieved 2009-12-30.

- ↑ Dedace, Sophia R. (2009-12-30). "Mayon watch: An inside look at the Phivolcs headquarters". GMA News.TV. Retrieved 2009-12-30.

- ↑ {{http://www.rappler.com/nation/145604-phivolcs-warning-big-mayon-volcano-eruption}}

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mayon. |

- Climbing Mayon Volcano

- Philippine Institute of Volcanology and Seismology (PHIVOLCS) Mayon Volcano Page

- Mayon Volcano Observatory

- Majestic Mt. Mayon – Cagsawa Ruin Park – images by Jenny Exconde.

- NASA Earth Observatory page

- Smithsonian Global Volcanism Program – Mayon