Echo parakeet

| Echo parakeet | |

|---|---|

_-at_Durrell_Trust.jpg) | |

| Female | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Psittaciformes |

| Superfamily: | Psittacoidea |

| Family: | Psittaculidae |

| Subfamily: | Psittaculinae |

| Tribe: | Psittaculini |

| Genus: | Psittacula |

| Species: | P. eques |

| Binomial name | |

| Psittacula eques (Boddaert, 1783) | |

| Subspecies | |

| |

| |

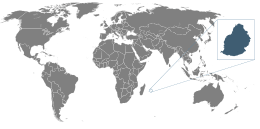

| Current range | |

| Synonyms | |

The echo parakeet or Mauritius parakeet (Psittacula eques), is a parrot endemic to Mauritius in the southern Indian Ocean. It is the only extant parrot of the Mascarene islands, all others have become extinct due to human activity. The extinct Réunion parakeet of Réunion was previously considered a distinct species, but a 2015 DNA study determined it to be a subspecies of the same species as the Mauritius population. If the Mauritius and Réunion birds are considered the same species, and the subspecies model is considered, then the Echo parakeet becomes the English group name for both, with the Mauritian birds using the scientific name Psittacula eques echo.

Taxonomy

Its scientific name change from Psittacula echo had recently found widespread approval. A wealth of circumstantial evidence nowadays suggests that the hypothesized Réunion parakeet (described earlier as Psittacula eques, based on a painting and hearsay reports) did indeed exist. The Réunion birds were the closest relatives, and presumably conspecific, with the Mauritius ones.[2]

A study skin had been discovered at the Royal Museum of Scotland, explicitly referencing a book description of the Réunion birds. This may be the only material proof of these birds' existence, or be from Mauritius. Even in that case, ancient DNA analysis of this specimen will give new insight into these questions, because very little data exists on the genetic diversity of the Mauritius parakeet in former times.

In any case, the Réunion and Mauritius birds certainly formed a clade. Until the new DNA data is available – and even then only if it would show a significant difference -, it is really a matter of opinion whether one follows a lumper or a splitter approach.

Evolution

Many extant or extinct birds endemic to the Mascarene Islands are derived from South Asian ancestors, including the dodo, and a South Asian provenance has been proposed for the parrots as well. Sea levels were lower during the Pleistocene, so it was possible for species to "island hop" to the isolated islands. Of the about eight endemic Mascarene parrot species, all but the Mauritius parakeet have gone extinct. In spite of many of them being poorly known, fossil remains show that they shared features such as enlarged heads and jaws, reduced pectoral elements, and robust leg elements. Julian Hume has suggested their common origin is within the Psittaculini radiation, based on morphological features and the fact that Psittacula parrots have managed to colonise many isolated islands in the Indian Ocean.[3] This group may have invaded the area several times, as many of the species were so specialised that they may have diverged on hot spot islands before the Mascarenes emerged from the sea.[4] However, a 2012 genetic study showed that the Mascarene parrot was nested among the subspecies of the lesser vasa parrot from Madagascar and nearby islands, and was therefore not related to the Psittacula parrots.[5] This is surprising, due to its anatomical similarities with other Mascarene parrots that are believed to be Psittaculines.[6]

The following cladogram shows the phylogenetic position of the Mauritius and Réunion subspecies, according to Jackson et al., 2015:[7]

| |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |

However, Hume and Justin J. F. J. Jansen pointed out in 2016 that the sole specimen thought to be a Réunion parakeet has no clear provenance information, and may simply be a Mauritius bird. They also doubted whether the birds of Réunion and Mauritius were different species.[8]

Description

It is generally similar to the rose-ringed parakeet—its closest living relative—except that the Mascarenes bird is a stockier species with a markedly shorter tail and a more intensive emerald green. The females lack the neck collar, and notably possess an all-black beak, unlike the males which have a red upper beak. The latter feature is notably absent in the rose-ringed parakeet as well as the Alexandrine parakeet, which is also generally similar and not too distantly related. However, it is found in the red-breasted parakeet, the Derbyan parakeet and the Nicobar parakeet which are morphologically dissimilar and apparently very closely related among each other, though not to the Mauritius parakeet or its immediate relatives.[9]

Conservation

The Mauritius parakeet is one of the most remarkable successes of wildlife conservation.

In the early 1980s, this parakeet was almost extinct. The roughly 10 birds that were left had hardly ever bred successfully since the early 1970s due to lack of suitable trees, nest predation,[10] disturbance by humans and feral pigs and deer, and competition with more plentiful bird species including the introduced rose-ringed parakeet. The Mauritius parakeet seemed doomed to extinction.

But with the team of Carl Jones (of Mauritius kestrel and Last Chance to See fame) taking over, a dedicated research and conservation effort was launched to save the birds. By the late 1980s, the situation had stabilized – though at a precariously low level – and more young birds were being hatched. By the mid-1990s, some 50–60 individuals were known altogether (including young birds) and an intensive management of the wild population by the Mauritian Wildlife Foundation could begin. These efforts paid off handsomely; by January 2000, the population had exceeded 100 birds total.

Since then, the rapid recovery has continued. The total wild population is presently some 280-300 individuals of which some 200 are adult, half of which being breeding pairs and most of the other half single males.[11] A captive fall-back population was originally held at the Gerald Durrell Endemic Wildlife Sanctuary, however only one individual male remains of the collection.[12]

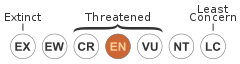

Recognizing that the Mauritius parakeet was not acutely threatened with extinction anymore but "merely" very rare, it is downlisted from critically endangered to endangered in the 2007 IUCN Red List. The goal for the near future is to have a stable population of 300 mature birds in the wild by 2010, and it is most likely that this will be achieved. At present, not all remaining and reconstituted habitat is utilized by the birds, so that it's hoped that the population will continue to expand in the near future. It is still threatened by unforeseeable events like tropical cyclones and psittacine beak and feather disease, the impact of which is at present unknown, and of course the threats which had brought it to near-extinction only some two decades ago continue to hamper its recovery.[13]

Footnotes

- ↑ Birdlife Intetrnational (2013). "Psittacula eques". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2014.3. International Union for Conservation of Nature. Retrieved 5 January 2015.

- ↑ BirdLife International (2006, 2007b), Hume (2007)

- ↑ Hume, Julian Pender (2007): Reappraisal of the parrots (Aves: Psittacidae) from the Mascarene Islands, with comments on their ecology, morphology, and affinities. Zootaxa 1513: 1–76 PDF abstract.

- ↑ Cheke, A. S.; Hume, J. P. (2008). Lost Land of the Dodo: an Ecological History of Mauritius, Réunion & Rodrigues. T. & A. D. Poyser. ISBN 978-0-7136-6544-4.

- ↑ Kundu, S.; Jones, C. G.; Prys-Jones, R. P.; Groombridge, J. J. (2011). "The evolution of the Indian Ocean parrots (Psittaciformes): Extinction, adaptive radiation and eustacy". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 62 (1): 296–305. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2011.09.025. PMID 22019932.

- ↑ Hume, J. P.; Walters, M. (2012). Extinct Birds. A & C Black. ISBN 140815725X.

- ↑ Jackson, H.; Jones, C. G.; Agapow, P. M.; Tatayah, V.; Groombridge, J. J. (2015). "Micro-evolutionary diversification among Indian Ocean parrots: temporal and spatial changes in phylogenetic diversity as a consequence of extinction and invasion". Ibis. 157 (3): 496–510. doi:10.1111/ibi.12275.

- ↑ Cheke, Anthony S.; Jansen, Justin J. F. J. "An enigmatic parakeet – the disputed provenance of an Indian Ocean Psittacula". Ibis. 158 (2): 439–443. doi:10.1111/ibi.12347.

- ↑ See Juniper & Parr (1998), Groombridge et al. (2006) for details.

- ↑ Mainly by black rats and crab-eating macaques: BirdLife International (2007b).

- ↑ There was and still is a surplus of males, which continue to be about thrice as numerous as females.

- ↑ See BirdLife International (2007b) for a detailed report of the species' recovery

- ↑ See BirdLife International (2006, 2007a,b).

References

- BirdLife International (2004). "Psittacula eques". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2006. International Union for Conservation of Nature. Retrieved 11 May 2006.

- BirdLife International (2007a): [ 2006-2007 Red List status changes ]. Retrieved 2007-AUG-26.

- BirdLife International (2007b): Mauritius Parakeet - BirdLife Species Factsheet. Retrieved 2007-AUG-28.

- Groombridge, Jim J.; Jones, Carl G.; Nichols, Richard A.; Carlton, Mark & Bruford, Michael W. (2004): Molecular phylogeny and morphological change in the Psittacula parakeets. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 31(1): 96-108. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2003.07.008 (HTML abstract)

- Hume, Julian Pender (2007): Reappraisal of the parrots (Aves: Psittacidae) from the Mascarene Islands, with comments on their ecology, morphology, and affinities. Zootaxa 1513: 1–76 PDF abstract.

- Juniper, Tony & Parr, Mike (1998): Parrots: A Guide to Parrots of the World. Christopher Helm, London. ISBN 1-873403-40-2

External links

- World Parrot Trust Parrot Encyclopedia – Species Profiles

- Brief synopsis and photo. Retrieved 2007-AUG-28.

- Detailed description of the recovery effort with many photos. Retrieved 2007-AUG-28.