Maui's dolphin

| Cephalorhynchus hectori maui | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Synapsida |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Artiodactyla |

| Infraorder: | Cetacea |

| Family: | Delphinidae |

| Genus: | Cephalorhynchus |

| Species: | C. hectori |

| Subspecies: | C. h. maui |

| Trinomial name | |

| Cephalorhynchus hectori maui Baker et al., 2002 | |

Maui's dolphin or popoto (Cephalorhynchus hectori maui) is the world's rarest and smallest known subspecies of dolphin.[1]

They are a subspecies of the Hector's dolphin. Maui's dolphins are only found off the west coast of New Zealand's North Island. Hector's and Maui's are New Zealand's only endemic cetaceans.[2] Maui's dolphins are generally found close to shore in groups or pods of several dolphins. They are generally seen in water shallower than 20 m, but may also range further offshore.

The dolphin is threatened by set-netting and trawling. Based on estimates from 2012, in May 2014, the World Wildlife Fund in New Zealand launched "The Last 55" campaign, calling for a full ban over what it believed is their entire range.[3][4] The International Whaling Commission supports more fishing restrictions, but the New Zealand government has resisted the demands and questioned the reliability of the evidence presented to the IWC that Maui's dolphins inhabit the areas they are said to inhabit.[5][6][7] In June 2014, the government decided to open up 3000 km2 of the West Coast North Island Marine Mammal Sanctuary – the main habitat of the Maui's dolphin – for oil drilling. This amounts to one-quarter of the total sanctuary area.[8] In May 2015, estimates suggested that the population had declined to 43-47 individuals, of which only 10 were mature females.[9]

Etymology

The word "Maui" from the Maui's dolphin's name comes from te Ika-a-Māui, the Māori word for New Zealand's North Island. However, the Māori word for the dolphin itself is popoto.[10]

Genetics

In 2002, Maui's dolphins were classified as a subspecies of Hector's dolphin. Previously, they had been known as the North Island Hector's dolphin. Dr Alan Baker found genetic and skeletal differences in the Maui's dolphins which made them distinct from others in the Hector's species.[11] These significant differences over a small geographical distance have not been found in any other studies of marine mammals.[12] So far, 26 different mitochondrial DNA identification haplotypes have been found in the Hector's species, the Maui's ‘G' haplotype being one of them.[13]

In 2002, Hector's dolphins were not known to be capable of swimming from the South Island to the North Island and co-existing with Maui's dolphins. Instead, the deep waters of the strait were understood to have been an effective barrier between South Island Hector's and North Island Maui's subspecies for between 15,000 and 16,000 years.[13] The 2012 Auckland University/Department of Conservation boat survey tissue sampling of Maui's in core range, which included historical samples, revealed three Hector's dolphins identified in this range area (two of them alive) along with another five Hector's being disclosed or sampled between Wellington and Oakura between 1967 and 2012.[14]

No evidence so far indicates the Hector's and Maui's dolphins interbreed,[14][15] but given their close genetic composition, they likely could. Interbreeding may increase the numbers of dolphins in the Maui's range and reduce the risk of inbreeding depression, but such interbreeding could eventually result in a hybridisation of the Maui's back into the Hector's species and lead to a reclassification of Maui's as again the North Island Hector's. Hybridisation in this manner threatens the Otago black stilt[16] and the Chatham Islands' Forbes parakeet[17] and has eliminated the South Island brown teal as a subspecies.[18] Researchers have also identified potential interbreeding as threatening the Maui's with hybrid breakdown and outbreeding depression.

Physical description

Having distinctive grey, white, and black markings and a short snout, they are most easily recognized by their round dorsal fins. Maui's dolphins are generally found close to shore in groups or pods of several dolphins. They have solidly built bodies with gently sloping snouts and a unique rounded dorsal fins. (Maui's and Hector's are the only dolphins with well-rounded black dorsal fins.) Females grow to 1.7 m long and weigh up to 50 kg. Males are slightly smaller and lighter. The dolphins are known to live up to 20 years.

Population, distribution and presence of Hector's

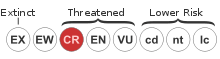

Maui's dolphins are listed on the IUCN Red List as Critically Endangered, and by the Department of Conservation in the New Zealand Threat Classification System as "Nationally Critical".[19]

Maui's dolphins are only found off the west coast of the North Island of New Zealand. The current range of the Maui's extends from Maunganui Bluff in the north to Whanganui in the south. There are occasional sightings off the east coast of the North Island between Wellington and the Bay of Plenty, which indicates more widespread and larger previous Maui's or Hector's populations.[12] Historical presence has been confirmed by DNA analysis to at least Wellington Harbour.[20]

A DOC survey report in 2012 estimated 55 adult Maui's dolphins remained.[21] This is a marked decrease from a 2004 survey that found the population to be around 100 dolphins.[22] A survey of Maui's dolphins in 1985 estimated their numbers to be at 134.[11] The data from the 2012 report are not directly comparable with earlier aerial surveys because of the different methods used and the 2012 survey effort had concentrated on the area within one kilometre from shore, but the reports highlight that the population is very small and are indicative of a recent decline.[20]

Whether some Maui's dolphins are migrating southwards, or only Hector's migrating northwards into Taranaki waters, is a matter of debate. A dolphin, either a Hector's or Maui's, was caught in Taranaki waters in a set net off Cape Egmont on 2 January 2012. A dolphin, DNA tested as a Hector's, was found washed up on the Opunake beach on 26 April 2012.[23]

Cephalorhynchus dolphin sighting information released by DOC in September 2013 includes listing three public sightings of Hector's type dolphins along the coastline immediately north of Wellington in late 2011. Four other sightings occurred between Whanganui and Waitara in early 2012.[24] Another sighting was recorded along the Poverty Bay coast of the North Island at this time. Sightings of this type of dolphin along the coast north of Wellington are infrequent, with the DOC database reporting only seven since 1970.

Hector's dolphins occasionally migrate northwards from the South Island.[15] Hector's DNA was confirmed from strandings in 2005 at Peka Peka and in 1967 at Waikanae, along the Horowhenua coastline. The DNA evidence was inconclusive on whether they were migrating from the east or west coasts of the South Island. A "potential for a small and elusive resident population of Hector's dolphins along the southern part of the North Island, outside the current range of the Maui's dolphin, or along the northern part of the South Island between the East and West Coast populations of Hector's dolphins..." was found.

During the 2012/2013 summer, the DOC conducted five aircraft and six boat searches, between New Plymouth and Hawera, without seeing any Maui's or Hector's dolphins.[25] In the two years between July 2012 and July 2014, more than 900 MPI observer days had been conducted out to seven nautical miles from the Taranaki shoreline without sighting any Maui's or Hector's dolphins.[26]

In May 2015, estimates suggested that the population of Maui's dolphins had declined to 43-47 individuals, of which only 10 were mature females.[9]

Ecology and behaviour

Vocalizations and echolocation

Maui's dolphins use echolocation to navigate, communicate, and find their food. High-frequency ultrasonic clicks reflect back to the dolphin any objects found in the water.[27]

Foraging and predation

Maui's dolphins feed on small fish, squid, and ocean floor-dwelling species such as flatfish and cod.[28] Maui's dolphins spend much of their time making dives to find fish on the sea floor. They also find fish and squid in midwater and at times feed near the surface.[27]

Social behaviour and reproduction

Female Maui's dolphins are not sexually mature until they are 7 - 9 years of age. They then produce one calf every 2 - 4 years.[29]

They have been observed playing (e.g. with seaweed), chasing other dolphins, blowing bubbles, and play fighting.[23]

Very little is known about the Maui's dolphin's reproductive physiology.

Threats

Since records began in 1921, 45 cases of deceased Maui's dolphins have been recorded, though at least six have turned out to be Hector's.[15] According to the Department of Conservation's Incident Database, 31 of these dolphins either did not have their cause of death assessed or it was unknown. Six deaths were linked to possible or known net entanglement, six deaths to natural causes, and two deaths to human interaction.[30]

Fishing

Dolphins can get entangled in nets and drown.[31] The DOC Incident Database contains no reports of a Maui's dolphin mortality in a trawl net.[20]

Some groups in the fishing industry are against increased bans on set nets into waters further offshore and inside harbours, and say other factors are responsible for the decline in the population, including disease, pollution, mining, and natural predation.[32]

Since the first major restrictions on commercial fishing to protect Maui's dolphins were imposed in 2003, 12 mortalities have been listed along the west coast of the North Island. Of these, three have been confirmed as Hector's dolphins and the deaths of all but one were from natural causes. The single death attributed to fishing occurred in January 2012.[33] The most recent dolphin death reported was from old age, with no indications of fishing injury, and she was found on a beach near Dargaville on 13 September 2013. An analysis of microsatellite DNA shows the dolphin was a Maui's.

This DOC Incident Database information is contrary to a NABU paper submitted to the Scientific Committee of the International Whaling Commission in June 2013, which referred back to the database that the number of fatal Maui's entanglements in fishing nets has increased, from an average of one per year, to 1.33 per year, since 2008.[34]

In 2012, the majority of a government-appointed panel of experts estimated that set-netting and trawling resulted in an average of five Maui's dolphin deaths each year.[3]

Disease

In 2006, Brucella was found in a dead Maui's dolphin and DOC says this bacterial infection could have serious ramifications for the small Maui's population. Brucellosis is a disease of terrestrial mammals that can cause late pregnancy abortion, and has been seen in a range of cetacean species elsewhere,[35] though not so far in Hector's or Maui's dolphins.

In 2012, post mortem studies on Hector's and Maui's showed that most were infected with the protozoa Toxoplasma. Two of the three Maui's dolphins were killed by toxoplasmosis. Toxoplasmosis is known to reduce fertility in livestock, with cats playing a key role in its transmission. It is not known how toxoplasmosis spread to Maui's and Hector's dolphins, nor is any funding available for research into this.[20] though Auckland City Council has decided to assist Massey University research by providing cat fecal samples.[36]

Fishing restrictions

In 2003, a ban on using commercial set nets was added to an existing ban on recreational set netting from Maunganui Bluff (north of Auckland) to Pariokariwa Point (north Taranaki), out to four nautical miles from shore.[37] In 2008, the restriction on set netting was extended out to seven nautical miles from shore along the same coastal area. In 2008, the existing ban on trawling one nautical mile from this coast was extended to two nautical miles and extended to four nautical miles between Manukau Harbour and Port Waikato.

Set netting is prohibited inside the entrances of the Kaipara, Manukau, and Raglan Harbours and Port Waikato. Current presence of Maui's dolphins further within these harbours is disputed, though they do visit the harbour mouths. After what MPI believed at the time in January 2012 was the capture of a Maui's dolphin off Taranaki (though now says it was 'about as likely as not' to have been a Hector's) in June 2012, the New Zealand government announced an interim set net ban extension south around the Taranaki coast to Hawera and out to two nautical miles from shore,[38][39] and set netting only with government observers on board between two and seven nautical miles from land.

In November 2013, the Minister of Conservation Nick Smith, in finalising the Maui's dolphin Threat Management Plan, confirmed[40] an increase of the Taranaki set net ban of two nautical miles, further out to seven nautical miles between Pariokariwa Point and Waiwhakaiho River near New Plymouth. He said this was due to five public sightings of Hector type dolphins off Waitara since 2006.[41] Smith also announced codes of practice for seismic surveys would be implemented, regulations for inshore boat racing and the establishment of a Maui's dolphin Research Advisory Group.

DOC's 2014–2015 Conservation Services Programme provides for all set net vessels off Taranaki to continue to have MPI observers on board, with 420 days of MPI observer coverage budgeted for the year to 30 June 2015. Many of the trawl vessels in the area will also now have MPI observers on board to look for Maui's dolphins, with 300 observer days budgeted.[42]

References

- ↑ "Dolphin's death reignites calls for set net ban". New Zealand Herald. APNZ. 1 February 2012. Retrieved 9 November 2014.

- ↑ Frankham, James. "Maui's dolphin – deep trouble". New Zealand Geographic. p. 34–. Retrieved 9 November 2014.

- 1 2 Hassan, Mohamed (19 May 2014). "Maui's dolphin danger: 'We're running out of time'". New Zealand Herald. APNZ. Retrieved 9 November 2014.

- ↑ Walters, Laura (19 May 2014). "Dolphin numbers perilously low". stuff.co.nz. Retrieved 9 November 2014.

- ↑ Morton, Jamie (10 June 2014). "NZ 'needs to do the right thing' to save Maui's dolphin". New Zealand Herald.

- ↑ "New Zealand rejects calls to further protect Maui's dolphin". Agence France-Presse. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 12 June 2014.

- ↑ "WWF responds to Minister's 'challenge' on Maui's dolphins". scoop.co.nz. 11 June 2014.

- ↑ "Oil and gas risk to Maui's dolphin 'small' – Minister". New Zealand Herald. 18 June 2014. Retrieved 2014-06-18.

- 1 2 Briggs, Helen (26 May 2015). "'Loud wakeup call' over critically endangered dolphin". BBC News.

- ↑ "Maui's dolphins- An Overview". WWF. Retrieved 14 November 2012.

- 1 2 "Maui's dolphin". WWF. Retrieved 9 March 2012.

- 1 2 "Cephalorhynchus hectori ssp. maui". International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources. Retrieved 2 April 2012.

- 1 2 Hamner, Rebecca M.; Pichler, Franz B.; Heimeier, Dorothea; Constantine, Rochelle; Baker, C. Scott (August 2012). "Genetic differentiation and limited gene flow among fragmented populations of New Zealand endemic Hector's and Maui's dolphins". Conservation Genetics. 13 (4): 987–1002. doi:10.1007/s10592-012-0347-9.

- 1 2 Hamner, Rebecca M.; Oremus, Marc; Stanley, Martin; Brown, Phillip; Constantine, Rochelle; Baker, C. Scott. "Estimating the abundance and effective population size of Maui's dolphins using microsatellite genotypes in 2010–11, with retrospective matching to 2001–07" (PDF). New Zealand Department of Conservation. Retrieved December 2012. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - 1 2 3 Hamner, Rebecca M.; Constantine, Rochelle; Oremus, Marc; Stanley, Martin; Brown, Phillip; Baker, C. Scott (2013). "Long-range movement by Hector's dolphins provides potential genetic enhancement for critically endangered Maui's dolphin". Marine Mammal Science. doi:10.1111/mms.12026.

- ↑ Wallis, G. "Genetic status of New Zealand black stilt (Himantopus novaezelandiae ) and impact of hybridisation" (PDF). New Zealand Department of Conservation.

- ↑ Greene, T.C. "Forbes' parakeet (Cyanoramphus forbesi) population on Mangere Island, Chatham Islands" (PDF). New Zealand Department of Conservation. Retrieved December 2012. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ Gemmel, N.J. "Taxonomic status of the brown teal (Anas chlorotis) in Fiordland" (PDF). New Zealand Department of Conservation. Retrieved December 2012. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ Hitchmough, Rod; Bull, Leigh; Cromarty, Pam (compilers) (2007). New Zealand Threat Classification System lists – 2005 (PDF). Wellington: Science & Technical Publishing, Department of Conservation. p. 32. ISBN 0-478-14128-9..

- 1 2 3 4 "Review of the Maui's Dolphin Threat Management Plan" (PDF). New Zealand Department of Conservation and Ministry for Primary Industries. Retrieved 12 September 2016.

- ↑ New Zealand Department of Conservation. "Maui's dolphin abundance estimate: DOC's work". Retrieved 9 November 2014.

- ↑ Slooten, Elisabeth; Dawson, Stephen; Rayment, William; Childerhouse, Simon (April 2006). "A new abundance estimate for Maui's dolphin: What does it mean for managing this critically endangered species?". Biological Conversation. 128 (4): 576–581. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2005.10.013.

- 1 2 Interim set net measures to protect Maui's dolphins, final advice paper. New Zealand Ministry for Primary Industries. 10 June 2012.

- ↑ "Maui's dolphin sightings database spreadsheet". NZ Department of Conservation.

- ↑ "Consultation on a proposed variation to the West Coast North Island Marine Mammal Sanctuary to prohibit commercial and recreational set net fishing between two and seven nautical miles offshore between Pariokariwa Point and the Waiwhakaiho River, Taranaki." (PDF). New Zealand Department of Conservation. 6 September 2013. Retrieved 9 November 2014.

- ↑ Smith, Nick (30 July 2014). "Greens' dolphin plan does not make sense". Scoop. Retrieved 9 November 2014.

- 1 2 "Maui's dolphin – Ecology". WWF. Retrieved 10 March 2012.

- ↑ "Dolphins and Porpoises (Families Delphinidae and Phocoenidae)". Treasures of the sea. Retrieved 2012-03-15.

- ↑ "Facts about Maui's dolphin". Department of Conservation. Retrieved 9 March 2012.

- ↑ "Hector's and Maui's incidents 1921–2008". Department of Conservation. Retrieved 30 July 2013.

- ↑ http://www.fish.govt.nz/en-nz/Environmental/Hectors+Dolphins/default.htm

- ↑ "Threats to Maui's dolphins". Department of Conservation.

- ↑ "Hector's and Maui's incidents 1921–2008". Department of Conservation. Retrieved 30 July 2013.

- ↑ Maas, Barbara (2013). "Science-based management of New Zealand's Maui's dolphins" (PDF). Scientific Committee Annual Meeting 2013. Retrieved 9 November 2014.

- ↑ "Threats not caused by people – disease". New Zealand Department of Conservation. Retrieved December 2012. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ "March 2014 Minutes of the Environment, Climate Change and Natural Heritage Committee". Auckland City Council.

- ↑ "Interim Set Net Measures to manage the risk of Maui's dolphin Mortality" (PDF). Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry. 14 March 2011. ISBN 978-0-478-38808-4. Retrieved 12 July 2012.

- ↑ Small, Vernon. "Set net ban extension to protect Maui's Dolphin". stuff.co.nz. Retrieved 9 November 2014.

- ↑ Cumming, Geoff (3 November 2012). "Maui's dolphin swimming in sea of trouble". New Zealand Herald.

- ↑ Smith, Nick; Guy, Nathan (25 November 2013). "Additional Protection and Survey Results Good News for Dolphins". NZ Government. Retrieved 9 November 2014.

- ↑ Smith, Nick (6 September 2013). "Additional protection proposed for Maui's dolphin". Minister of Conservation. Retrieved 9 November 2014.

- ↑ "Conservation Services Programme, Annual Plan 2014/15" (PDF). Department of Conservation. Department of Conservation. May 2014. Retrieved 9 November 2014.

External links

- Department of Conservation – Maui's dolphin page

- Forest and Bird – Maui's dolphin page

- Whale and Dolphin Conservation Society

- Mauis Dolphin New Zealand Event Information Maui's Dolphin New Zealand Event Information

- World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) – species profile for Maui's dolphin

- http://www.touscoprod.com/en/project/produce?cleanname=sauvezledauphinmaui