MAUD Committee

The MAUD Committee was founded by Winston Churchill, in response to Rudolf Peierls and Otto Frisch's memorandum, in June 1940. Their memorandum was a discussion of the potential relative ease of obtaining a nuclear bomb, compared to earlier projections. All the work in the Frisch-Peierls Memorandum was purely theoretical,[1] so the purpose of the MAUD committee was to do the research required for what Frisch and Peierls called a super bomb. The MAUD Committee investigated if applying nuclear technology to make a bomb was, in reality, feasible.[2] The chair of the committee was Thomson. Each university where research was being done had a commander as well. All the research finally culminated, after fifteen months,[3] in two reports - 'Use of Uranium for a Bomb' and 'Use of Uranium as a source of power' - known collectively as the MAUD report. These reports discussed the necessity of a super-bomb for the war effort. In order to research this further, the British created their own nuclear program officially named Tube Alloys.

Frisch-Peierls Memorandum

Otto Frisch and Rudolf Peierls began work on their combined memorandum in March 1940, three months before the formation of the MAUD committee. It was a three-page memorandum examining the theoretical possibility of a so-called 'super-bomb'. Its three pages were split up into two parts. The first part was a technical blueprint for a hypothetical atomic weapon. It was projected at the time that it would take over five pounds to produce the critical mass needed for an explosion. They projected a far less amount of uranium needed to produce a critical mass, at around five kilograms for an equivalent to several thousand tons of dynamite.[4] However, even a one kilogram bomb would be impressive .[5] The second portion of the memorandum dealt with possible strategies of using the atomic bomb. They were the first to realize that there could be an issue with fallout. Because of the potential fallout, they thought that the British would find it morally unacceptable. Shortly after, Winston Churchill formed the Maud Committee to research this problem in more detail.[4]

The Thomson Committee

The committee was first named after its chair, George Thomson. The Thomson Committee was quickly exchanged for a more unassuming name, the MAUD Committee.[2] MAUD is assumed by many to be an acronym, however it is not. The name MAUD came to be in an unusual way. Shortly after Germany invaded Denmark, Niels Bohr had sent a telegram to Otto Frisch. The telegram ended with a strange line "Tell Cockcroft and Maud Ray Kent".[6] At first it was thought to be code regarding radium or other vital atomic-weapons-related information, hidden in an anagram. One suggestion was to replace the y with an i, producing 'radium taken'. Regardless of how crazy it seemed it was enough to cause concern in Britain.[3] Years later, when Bohr returned to England in 1943, it was discovered that the message was addressed to Bohr's housekeeper Maud Ray and John Cockcroft. Maud Ray was from Kent. Thus the committee was named The M.A.U.D. Committee.[6]

Organization of the Committee

Originally constructed under the Committee for the Scientific Survey of Air Warfare,[6] the MAUD Committee achieved independence in June 1940 with the Ministry of Aircraft Production. The MAUD Committee had been created as a response to the Peierls-Frisch's memorandum.[2] Because of the top secret aspect of the project, only British born scientist were considered. Even despite their early contributions, Peierls and Frisch were not allowed to participate in the MAUD committee because, at a time of war, it was considered a security threat to have 'enemy aliens' working on a sensitive project. However, because of the manpower needed to accomplish the project, the Ministry began to recruit ex-aliens or aliens. However, they did not have contracts directly with the individual scientist; their contracts were held with the universities and the universities could hire whomever they wanted. Even before they began to recruit ex-aliens, Peierls and Frisch had made great contributions to the project. After a letter to the Committee head Thomson, it was agreed that Peierls and Frisch would not be a part of the policy committee. A technical sub-committee was formed with Peierls and Frisch to deal with the separation of uranium.[7] The MAUD Policy Committee members were:[6]

- George Thomson (Chairman)

- James Chadwick

- John Cockcroft

- Marcus Oliphant

- Patrick Blackett

- Charles Ellis

- William Haworth

- Philip Moon

The Policy was kept small and included only certain representatives from each University Lab. The members of the technical committee were the only scientists who worked in the laboratories, including the 'enemy aliens'.[8]

The MAUD Committee's research was split among four different laboratories. Before the fall of 1940, all work was lab research was done at universities, due to strict government regulations. These universities included the University of Liverpool, the University of Birmingham, the University of Oxford, and the University of Cambridge. Each of these laboratories functioned as separate entities of a single system .[9] At first the research was paid for mainly out of the universities own pockets. In the fall of 1940 this changed, the Ministry of Aircraft production signed contracts that promised additional funding for each university. The Ministry gave 3,000 pounds to the laboratory at Cambridge, 1,000 pounds to the laboratory at Oxford, 1,500 pounds to the laboratory at Birmingham, and 2,000 pounds to the laboratory at Liverpool. They also began to pay some university staff's salary. Chadwick, Peierls, and other professors were still paid from university funds. The university provided materials and extra scientists for each of the participating university laboratories.[10]

Liverpool University

The division of the MAUD Committee at Liverpool was led by James Chadwick. At Liverpool they focused on the separation of isotopes through thermal diffusion as was suggested in the Frish/Peierls memorandum. This process is based on the ability of uranium 235 to disperse to a hot surface, while uranium 238 would disperse to a cold surface. Another area of research at Liverpool was to find the probability of actually making a nuclear bomb through cross-sections.[11]

The University of Oxford

The division of the MAUD Committee at Oxford was led by Franz Simon, a German émigré. Simon, who was at risk of exclusion because he was a German émigré, was only able to get involved because of Rudolf Peierls. Peierls pointed out that Simon had already begun research on isotope separation, so the project would get a head start by his participation. The Oxford team was composed mostly non-British scientists, including Nicholas Kurti, Kurt Mendlssohn, and Heinz London. The Oxford team concentrated on isotope separation with a method known as gaseous diffusion.[12]

The University of Cambridge

The division of the MAUD Committee at Cambridge was led by Professor Rideal. This lab tackled two major problems. First they theorized that another element, Plutonium, could be used for a bomb. Even though it would have no impact on the program at the time.[13] Secondly two French scientists, Dr. Halban and Dr. Kowarski, formed the world's first supply of heavy water. This would have no impact on the bomb but would later be used in a nuclear reactor, to help produce nuclear energy in the future.[14]

The University of Birmingham

The division of the MAUD Committee at Birmingham was led by Rudolf Peierls. Peierls and his crew continued worked on the theoretical problems of a nuclear bomb. In essence they were in charge of finding out the technical features of the bomb. They worked on the specifics of a bomb. Also, along with Klaus Fuchs, Peierls interpreted all the experimental data from the other laboratories: Liverpool, Oxford and Cambridge. Peirels also examined the different processes by which they were obtaining isotopes. By the end of the summer in 1940, Peirels preferred gaseous diffusion to thermal diffusion.[14]

First meetings

At Tizard's behest, the Maud Committee first met on 10 April 1940 to consider Britain's actions regarding the "uranium problem". A research programme on isotope separation and fast fission was agreed upon. In June 1940 Franz Simon was commissioned to research on isotope separation through gaseous diffusion. Ralph H. Fowler was also asked to send the progress reports to Lyman Briggs in America from that date.

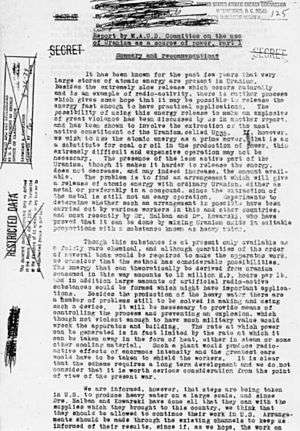

The MAUD Report

The MAUD report was a report on the findings of all the research the MAUD Committee did. The report actually came out as two separate reports: 'Use of Uranium as a Source of Power' and 'Use of Uranium for a Bomb'. While some of the report was still theoretical, the reports did answer big questions like, why the uranium 235 was the only possible isotope for a chain reaction, or why it would be a super bomb. The MAUD report was a consolidation of all the research and experiments the MAUD Committee had completed. In July 1941, Dr. Lauritsen, a United States physicist, visited a MAUD committee meeting where the report was being discussed. He immediately took it back to the United States and brought it to Washington. The United States, who at this time was focused more on the application of uranium as source of power, instantly began work on its own atomic bomb. The MAUD report jump-started the Manhattan Project. Without the MAUD project the Manhattan Project would have been months behind. The MAUD report also catalyzed the formation of the British nuclear program: Tube Alloys.[15]

Chadwick's final draft, July 1941; telling the USA

After months of growing pressure from scientists in Britain and in the US (particularly Berkeley's Ernest Lawrence), Vannevar Bush at the National Defense Research Committee (NDRC) decided to review the prospects of nuclear energy further. He engaged Arthur Compton and the National Academy of Sciences. Their report was issued 17 May 1941 but did not address the design or manufacture of a bomb in any detail.

On 15 July 1941 the MAUD Committee approved its two final reports and disbanded. One report was on 'Use of Uranium for a Bomb' and the other was on 'Use of Uranium as a Source of Power'.

The first MAUD report concluded that a bomb was feasible, described it in technical detail, and provided specific proposals for developing a bomb, including cost estimates. The bomb would contain about 12 kg of active material which would be equivalent to 1,800 tons of TNT, and release large quantities of radioactive substances which would make places near the explosion site dangerous to humans for a long period. A plant to produce 1 kg of U-235 per day would cost £5 million and would require a large skilled labour force that was also needed for other parts of the war effort. Germany could also be working on the bomb (though German efforts seemed concentrated on the future use of uranium for power and naval propulsion), and so work on the bomb should be continued with high priority in cooperation with the U.S.

The second MAUD Report concluded that the controlled fission of uranium could be used to generate heat energy for use in machines, and provide large quantities of radioisotopes which could be used as substitutes for radium. Heavy water or possibly graphite might serve as moderator for the fast neutrons. The 'uranium boiler' (i.e., a nuclear reactor) had considerable promise for future peaceful uses, but was not worth considering during the present war. The Committee recommended that Hans von Halban and Lew Kowarski should move to the U.S. where there were plans to make heavy water on a large scale. Plutonium might be more suitable than U-235, and plutonium research should be continued in Britain.

Britain was at war and felt an atomic bomb was urgent, but the US was not at war. It was Marcus Oliphant who pushed the American programme into action. Oliphant flew to the United States in late August 1941 in an unheated bomber, ostensibly to discuss the radar programme, but actually to find out why the United States was ignoring the MAUD Committee's findings. Oliphant reported: "The minutes and reports had been sent to Lyman Briggs, who was the Director of the Uranium Committee, and we were puzzled to receive virtually no comment. I called on Briggs in Washington, only to find out that this inarticulate and unimpressive man had put the reports in his safe and had not shown them to members of his committee. I was amazed and distressed."

Oliphant then met with the S-1 Section. Samuel K. Allison was a new committee member, a talented experimentalist and a protégé of Arthur Compton at the University of Chicago. Oliphant "came to a meeting," Allison recalls, "and said 'bomb' in no uncertain terms. He told us we must concentrate every effort on the bomb and said we had no right to work on power plants or anything but the bomb. The bomb would cost 25 million dollars, he said, and Britain did not have the money or the manpower, so it was up to us." Allison was surprised that Briggs had kept the committee in the dark.

Oliphant then visited his friend Ernest Lawrence and Enrico Fermi to explain the urgency. Lawrence then contacted Compton and James Conant. In October 1941, Vannevar Bush presented the final Report draft to the President, who ordered Bush to obtain the blessing for a Bomb Project from the National Academy of Sciences. In December, Bush created the larger and more powerful Office of Scientific Research and Development (OSRD), which was empowered to engage in large engineering projects in addition to research, and became its director, leading to the creation of the Manhattan Project. Meanwhile, in Britain a separate nuclear bomb programme continued under the code name Tube Alloys.

Soviet Union interest

By the end of 1941, spies within the British government had communicated the conclusions of the MAUD report to the Soviet KGB. In 1943 the NKVD obtained a copy of the final report by the MAUD Committee. This led Joseph Stalin to order the start of a Soviet programme, but with very limited resources. Igor Kurchatov was appointed director of the nascent programme later that year.[16]

Notes

- ↑ Gowing 1964, p. 41.

- 1 2 3 Laucht 2012, p. 41.

- 1 2 Szasz 1992, p. 5.

- 1 2 Szasz 1992, p. 4.

- ↑ Szasz 1992, p. 143.

- 1 2 3 4 Gowing 1964, p. 45.

- ↑ Gowing 1964, pp. 47-48.

- ↑ Gowing 1964, p. 48.

- ↑ Laucht 2012, p. 42.

- ↑ Gowing 1964, pp. 52-53.

- ↑ Laucht 2012, pp. 42-43.

- ↑ Laucht 2012, pp. 45-46.

- ↑ Laucht 2012, p. 43.

- 1 2 Laucht 2012, p. 44.

- ↑ Gowing 1964, pp. 77-80.

- ↑ Gannon 2001, p. 224.

References

- Gannon, James (2001). Stealing Secrets, Telling Lies: How Spies and Codebreakers Helped Shape the Twentieth Century. Potomac Books. ISBN 1574883674.

- Gowing, Margaret (1964). Britain and Atomic Energy 1939 - 1945 (1 ed.). New York: St. Martin's Press.

- Laucht, Christoph (2012). Elemental Germans: Klaus Fuchs, Rudolf Peierls and the making of British nuclear culture 1939-59. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Szasz, Ferenc Morton (1992). British Scientists and the Manhattan Project. New York: St. Martin's Press.