Maternal death

| Maternal death | |

|---|---|

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | obstetrics |

| ICD-10 | O95 |

| ICD-9-CM | 646.9 |

| Patient UK | Maternal death |

Maternal death is defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as "the death of a woman while pregnant or within 42 days of termination of pregnancy, irrespective of the duration and site of the pregnancy, from any cause related to or aggravated by the pregnancy or its management but not from accidental or incidental causes."[1]

The world mortality rate has declined 45% since 1990, but still every day 800 women die from pregnancy or childbirth related causes.[2] According to the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) this is equivalent to "about one woman every two minutes and for every woman who dies, 20 or 30 encounter complications with serious or long-lasting consequences. Most of these deaths and injuries are entirely preventable."[2]

UNFPA estimated that 289,000 women died of pregnancy or childbirth related causes in 2013.[2] These causes range from severe bleeding to obstructed labour, all of which have highly effective interventions . As women have gained access to family planning and skilled birth attendance with backup emergency obstetric care, the global maternal mortality ratio has fallen from 380 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births in 1990 to 210 deaths per 100,000 live births in 2013, and many countries halved their maternal death rates in the last 10 years.[2]

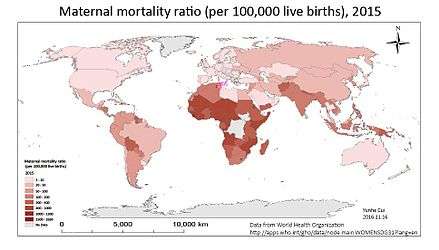

Worldwide mortality rates have been decreasing in modern age . High rates still exist, particularly in impoverished communities with over 85% living in Africa and Southern Asia.[2] The effect of a mother's death results in vulnerable families and their infants, if they survive childbirth, are more likely to die before reaching their second birthday.[2]

Causes

Factors that increase maternal death can be direct or indirect. Generally, there is a distinction between a direct maternal death that is the result of a complication of the pregnancy, delivery, or management of the two, and an indirect maternal death.[3] that is a pregnancy-related death in a patient with a preexisting or newly developed health problem unrelated to pregnancy. Fatalities during but unrelated to a pregnancy are termed accidental, incidental, or nonobstetrical maternal deaths.

The most common causes are postpartum bleeding (15%), complications from unsafe abortion (15%), hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (10%), postpartum infections (8%), and obstructed labour (6%).[4] Other causes include blood clots (3%) and pre-existing conditions (28%).[5] Indirect causes are malaria, anaemia,[6] HIV/AIDS, and cardiovascular disease, all of which may complicate pregnancy or be aggravated by it .

Sociodemographic factors such as age, access to resources and income level are significant indicators of maternal outcomes. Young mothers face higher risks of complications and death during pregnancy than older mothers,[7] especially adolescents aged 15 years or younger.[8] Adolescents have higher risks for postpartum hemorrhage, puerperal endometritis, operative vaginal delivery, episiotomy, low birth weight, preterm delivery, and small-for-gestational-age infants, all of which can lead to maternal death.[8] Structural support and family support influences maternal outcomes . Furthermore, social disadvantage and social isolation adversely affects maternal health which can lead to increases in maternal death.[9] Additionally, lack of access to skilled medical care during childbirth, the travel distance to the nearest clinic to receive proper care, number of prior births, barriers to accessing prenatal medical care and poor infrastructure all increase maternal deaths.

Unsafe abortion is another major cause of maternal death. According to the World Health Organization, every eight minutes a woman dies from complications arising from unsafe abortions. Complications include hemorrhage, infection, sepsis and genital trauma.[10] Globally, preventable deaths from improperly performed procedures constitute 13% of maternal mortality, and 25% or more in some countries where maternal mortality from other causes is relatively low, making unsafe abortion the leading single cause of maternal mortality worldwide.[11]

Measurement

The four measures of maternal death are the maternal mortality ratio (MMR), maternal mortality rate, lifetime risk of maternal death and proportion of maternal deaths among deaths of women of reproductive years (PM).

Maternal mortality ratio (MMR): the ratio of the number of maternal deaths during a given time period per 100,000 live births during the same time-period.[12] The MMR is used as a measure of the quality of a health care system.

Maternal mortality rate (MMRate): the number of maternal deaths in a population divided by the number of women of reproductive age, usually expressed per 1,000 women.[12]

Lifetime risk of maternal death: refers to the probability that a 15-year-old female will die eventually from a maternal cause if she experiences throughout her lifetime the risks of maternal death and the overall levels of fertility and mortality that are observed for a given population. The adult lifetime risk of maternal mortality can be derived using either the maternal mortality ratio (MMR), or the maternal mortality rate (MMRate). [12]

Proportion of maternal deaths among deaths of women of reproductive age (PM): the number of maternal deaths in a given time period divided by the total deaths among women aged 15–49 years.[13]

Approaches to measuring maternal mortality includes civil registration system, household surveys, census, reproductive age mortality studies (RAMOS) and verbal autopsies.[13]

Trends

According to the 2010 United Nations Population Fund report, developing nations account for ninety-nine percent of maternal deaths with the majority of those deaths occurring in Sub-Saharan Africa and Southern Asia.[13] Globally, high and middle income countries experience lower maternal deaths than low income countries. The Human Development Index (HDI) accounts for between 82 and 85 percent of the maternal mortality rates among countries.[14] In most cases, high rates of maternal deaths occur in the same countries that have high rates of infant mortality. These trends are a reflection that higher income countries have stronger healthcare infrastructure, medical and healthcare personnel, use more advanced medical technologies and have fewer barriers to accessing care than low income countries. Therefore, in low income countries, the most common cause of maternal death is obstetrical hemorrhage, followed by hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, in contrast to high income countries, for which the most common cause is thromboembolism.[15]

At a country level, India (19% or 56,000) and Nigeria (14% or 40,000) accounted for roughly one third of the maternal deaths in 2010 . Democratic Republic of the Congo, Pakistan, Sudan, Indonesia, Ethiopia, United Republic of Tanzania, Bangladesh and Afghanistan comprised between 3 and 5 percent of maternal deaths each.[13] These ten countries combined accounted for 60% of all the maternal deaths in 2010 according to the United Nations Population Fund report. Countries with the lowest maternal deaths were Estonia, Greece and Singapore.[16]

In the United States, the maternal death rate averaged 9.1 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births during the years 1979–1986,[17] but then rose rapidly to 14 per 100,000 in 2000 and 17.8 per 100,000 in 2009.[18] In 2013 the rate was 18.5 deaths per 100,000 live births, with some 800 maternal deaths reported.[19]

Variation within countries

There are significant maternal mortality intracountry variations, especially in nations with large equality gaps in income and education and high healthcare disparities. Women living in rural areas experience higher maternal mortality than women living in urban and sub-urban centers because[20] those living in wealthier households, having higher education, or living in urban areas, have higher use of healthcare services than their poorer, less-educated, or rural counterparts.[21] There are also racial and ethnic disparities in maternal health outcomes which increases maternal mortality in marginalized groups.[22]

Prevention

The death rate for women giving birth plummeted in the twentieth century. The historical level of maternal deaths is probably around 1 in 100 births.[23] Mortality rates reached very high levels in maternity institutions in the 1800s, sometimes climbing to 40 percent of birthgiving women (see Historical mortality rates of puerperal fever). At the beginning of the 1900s, maternal death rates were around 1 in 100 for live births. Currently, there are an estimated 275,000 maternal deaths each year.[24] Public health, technological and policy approaches are steps that can be taken to drastically reduce the global maternal death burden.

Four elements are essential to maternal death prevention, according to UNFPA.[2] First, prenatal care. It is recommended that expectant mothers receive at least four antenatal visits to check and monitor the health of mother and fetus. Second, skilled birth attendance with emergency backup such as doctors, nurses and midwives who have the skills to manage normal deliveries and recognize the onset of complications. Third, emergency obstetric care to address the major causes of maternal death which are hemorrhage, sepsis, unsafe abortion, hypertensive disorders and obstructed labour. Lastly, postnatal care which is the six weeks following delivery. During this time bleeding, sepsis and hypertensive disorders can occur and newborns are extremely vulnerable in the immediate aftermath of birth. Therefore, follow-up visits by a health worker to assess the health of both mother and child in the postnatal period is strongly recommended.

Medical technologies

The decline in maternal deaths has been due largely to improved asepsis, fluid management and blood transfusion, and better prenatal care.

Technologies have been designed for resource poor settings that have been effective in reducing maternal deaths as well. The non-pneumatic anti-shock garment is a low-technology pressure device that decreases blood loss, restores vital signs and helps buy time in delay of women receiving adequate emergency care during obstetric hemorrhage.[25] It has proven to be a valuable resource. Condoms used as uterine tamponades have also been effective in stopping post-partum hemorrhage.[26]

Public health

.jpg)

Most maternal deaths are avoidable, as the health-care solutions to prevent or manage complications are well known. Improving access to antenatal care in pregnancy, skilled care during childbirth, and care and support in the weeks after childbirth will reduce maternal deaths significantly . It is particularly important that all births be attended by skilled health professionals, as timely management and treatment can make the difference between life and death. To improve maternal health, barriers that limit access to quality maternal health services must be identified and addressed at all levels of the health system.[27] Recommendations for reducing maternal mortality include access to health care, access to family planning services, and emergency obstetric care, funding and intrapartum care.[28] Reduction in unnecessary obstetric surgery has also been suggested.

Family planning approaches include avoiding pregnancy at too young of an age or too old of an age and spacing births. Access to primary care for women even before they become pregnant is essential along with access to contraceptives.

Policy

The biggest global policy initiative for maternal health came from the United Nations' Millennium Declaration[29] which created the Millennium Development Goals. The fifth goal of the United Nations' Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) initiative is to reduce the maternal mortality rate by three quarters between 1990 and 2015 and to achieve universal access to reproductive health by 2015.[30]

Trends through 2010 can be viewed in a report written jointly by the WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, and the World Bank.[31]

Countries and local governments have taken political steps in reducing maternal deaths. Researchers at the Overseas Development Institute studied maternal health systems in four apparently similar countries: Rwanda, Malawi, Niger, and Uganda.[32] In comparison to the other three countries, Rwanda has an excellent recent record of improving maternal death rates. Based on their investigation of these varying country case studies, the researchers conclude that improving maternal health depends on three key factors: 1. reviewing all maternal health-related policies frequently to ensure that they are internally coherent; 2. enforcing standards on providers of maternal health services; 3. any local solutions to problems discovered should be promoted, not discouraged.

In terms of aid policy, proportionally, aid given to improve maternal mortality rates has shrunken as other public health issues, such as HIV/AIDS, have become major international concerns.[33] Maternal health aid contributions tend to be lumped together with newborn and child health, so it is difficult to assess how much aid is given directly to maternal health to help lower the rates of maternal mortality. Regardless, there has been progress in reducing maternal mortality rates internationally.[34]

Epidemiology

Maternal deaths and disabilities are leading contributors in women's disease burden with an estimated 275,000 women killed each year in childbirth and pregnancy worldwide.[24] In 2011, there were approximately 273,500 maternal deaths (uncertainty range, 256,300 to 291,700).[35] Forty-five percent of postpartum deaths occur within 24 hours.[36] Ninety-nine percent of maternal deaths occur in developing countries.[5]

See also

References

- ↑ "Health statistics and information systems: Maternal mortality ratio (per 100 000 live births)". World Health Organization. Retrieved June 17, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Maternal health". United Nations Population Fund. Retrieved 2016-03-22.

- ↑ Khlat, M. & Ronsmans, C. (2009). "Deaths Attributable to Childbearing in Matlab, Bangladesh: Indirect Causes of Maternal Mortality Questioned" (PDF). American Journal Of Epidemiology. 151 (3): 300–306.

- ↑ GBD 2013 Mortality and Causes of Death, Collaborators (17 December 2014). "Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013.". Lancet. 385: 117–71. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61682-2. PMC 4340604

. PMID 25530442.

. PMID 25530442. - 1 2 "Maternal mortality: Fact sheet N°348". World Health Organization. WHO. Retrieved 20 June 2014.

- ↑ The commonest causes of anaemia are poor nutrition, iron, and other micronutrient deficiencies, which are in addition to malaria, hookworm, and schistosomiasis (2005 WHO report p45).

- ↑ "Maternal mortality".

- 1 2 Conde-Agudelo A, Belizan JM, Lammers C (2004). "Maternal-perinatal morbidity and mortality associated with adolescent pregnancy in Latin America: Cross-sectional study". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 192 (2): 342–349. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2004.10.593. PMID 15695970.

- ↑ Morgan, K. J. & Eastwood, J. G. (2014). "Social determinants of maternal self-rated health in South Western Sydney, Australia". BMC Research Notes. 7 (1): 1–12. doi:10.1186/1756-0500-7-51. PMC 3899616

. PMID 24447371.

. PMID 24447371. - ↑ Haddad, L. B. & Nour, N. M. (2009). "Unsafe abortion: unnecessary maternal mortality". Reviews in obstetrics and gynecology. 2 (2): 122. PMC 2709326

. PMID 19609407.

. PMID 19609407. - ↑ Dixon-Mueller, Ruth; Germain, Adrienne (1 January 2007). "Fertility Regulation and Reproductive Health in the Millennium Development Goals: The Search for a Perfect Indicator". Am J Public Health. 97 (1): 45–51. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2005.068056. PMC 1716248

. PMID 16571693 – via PubMed Central.

. PMID 16571693 – via PubMed Central. - 1 2 3 "MME Info". maternalmortalitydata.org. Archived from the original on October 14, 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 [UNICEF, W. (2012). UNFPA, World Bank (2012) Trends in maternal mortality: 1990 to 2010. WHO, UNICEF.]

- ↑ Lee, K. S.; Park, S. C.; Khoshnood, B.; Hsieh, H. L. & Mittendorf, R. (1997). "Human development index as a predictor of infant and maternal mortality rates". The Journal of Pediatrics. 131 (3): 430–433. doi:10.1016/S0022-3476(97)80070-4. PMID 9329421.

- ↑ Venös tromboembolism (VTE) - Guidelines for treatment in C counties. Bengt Wahlström, Emergency department, Uppsala Academic Hospital. January 2008

- ↑ "Comparison: Maternal Mortality Rate". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency.

- ↑ Atrash HK, Koonin LM, Lawson HW, Franks AL, Smith JC (1990). "Maternal Mortality in the United States". Obstetrics and Gynecology. Centers for Disease Control. 76 (6): 1055–1060. PMID 2234713.

- ↑ "Pregnancy Mortality Surveillance System - Pregnancy - Reproductive Health". CDC.

- ↑ Morello, Carol (May 2, 2014). "Maternal deaths in childbirth rise in the U.S.". Washington Post.

- ↑ "WHO Maternal Health". WHO.

- ↑ Wang W, Alva S, Wang S, Fort A (2011). "Levels and trends in the use of maternal health services in developing countries" (PDF). Calverton, MD: ICF Macro. p. 85. (DHS Comparative Reports 26).

- ↑ Lu, M. C. & Halfon, N. (2003). "Racial and ethnic disparities in birth outcomes: a life-course perspective". Maternal and child health journal. 7 (1): 13–30. doi:10.1023/A:1022537516969. PMID 12710797.

- ↑ See, for instance, mortality rates at the Dublin Maternity Hospital 1784–1849.

- 1 2 Marge Koblinsky; Mahbub Elahi Chowdhury; Allisyn Moran; Carine Ronsmans (2012). "Maternal Morbidity and Disability and Their Consequences: Neglected Agenda in Maternal Health". J Health Popul Nutr. 30 (2): 124–130. JSTOR 23500057. PMC 3397324

. PMID 22838155.

. PMID 22838155. - ↑ S. Miller; J. M. Turan; K. Dau; M. Fathalla; M. Mourad; T. Sutherland; S. Hamza; F. Lester; E. B. Gibson; R. Gipson; et al. (2007). "Use of the non-pneumatic anti-shock garment (NASG) to reduce blood loss and time to recovery from shock for women with obstetric haemorrhage in Egypt". Glob Public Health. 2 (2): 110–124. doi:10.1080/17441690601012536. PMID 19280394. (NASG)

- ↑ Sayeba Akhter; FCPS; DRH; FICMCH; et al. (2003). "Use of a Condom to Control Massive Postpartum Hemorrhage" (PDF). Medscape general medicine. 5 (3): 38.

- ↑ "Reducing Maternal Mortality" (PDF). UNFPA. Retrieved September 1, 2016.

- ↑ Costello, A; Azad K; Barnett S (2006). "An alternative study to reduce maternal mortality". The Lancet. 368 (9546): 1477–1479. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69388-4.

- ↑ "A/res/55/2".

- ↑ "MDG 5: improve maternal health". WHO. May 2015. Retrieved September 1, 2016.

- ↑ "Trends in Maternal Mortality: 1990 to 2010" (PDF). WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, and the World bank. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- ↑ Chambers, V.; Booth, D. (2012). "Delivering maternal health: why is Rwanda doing better than Malawi, Niger and Uganda?" (Briefing Paper). Overseas Development Institute.

- ↑ "Development assistance for health by health focus area (Global), 1990-2009, interactive treemap". Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. Archived from the original on 2014-03-17.

- ↑ "Progress in maternal and child mortality by country, age, and year (Global), 1990-2011". Archived from the original on 2014-03-17.

- ↑ Bhutta, Z. A.; Black, R. E. (2013). "Global Maternal, Newborn, and Child Health — So Near and Yet So Far". New England Journal of Medicine. 369 (23): 2226–2235. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1111853.

- ↑ Nour NM (2008). "An Introduction to Maternal Mortality". Reviews in Ob Gyn. 1 (2): 77–81. PMC 2505173

. PMID 18769668.

. PMID 18769668.

Bibliography

- World Health Organization (2014). Trends in maternal mortality: 1990 to 2013 (PDF). WHO. ISBN 978 92 4 150722 6. Retrieved 2 August 2016.

External links

- Maternal Mortality in Central Asia, Central Asia Health Review (CAHR), 2 June 2008.

- Maternal Mortality Estimates 2000 by the WHO & UNICEF

- The World Health Report 2005 – Make Every Mother and Child Count

- Confidential Enquiry into Maternal and Child Health (CEMACH) - UK triennial enquiry into "Why Mothers Die"

- Reducing Maternal Mortality in Developing Countries - Video, presentations, and summary of event held at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, March 2008

- Birth of a Surgeon PBS documentary about midwives trained in surgical techniques in Mozambique

- Save A Mother Non-profit focused on MMR reduction.

- W4 Non-profit that supports mothers and their children to reduce maternal and infant mortality through safe births.

- The Global Library of Women's Medicine Safer Motherhood Section - non-profit offering freely downloadable material for healthcare professionals

- Maternal Mortality in the U.S. Merck for Mothers