Mass media and American politics

Mass media and American politics covers the role of newspapers, magazines, radio, television, and social media from the colonial era to the present.

Colonial and Revolutionary eras

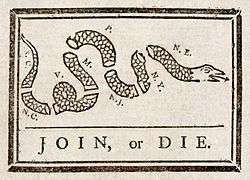

The first newspapers appeared in major port cities such as Philadelphia, New York, Boston, and Charleston in order to provide merchants with the latest trade news. They typically copied any news that was received from other newspapers, or from the London press. The editors discovered they could criticize the local governor and gain a bigger audience; the governor discovered he could shut down the newspapers. The most dramatic confrontation came in New York in 1734, where the governor brought John Peter Zenger to trial for criminal libel after his paper published some satirical attacks. Zenger's lawyers argued that truth was a defense against libel and the jury acquitted Zenger, who became the iconic American hero for freedom of the press. The result was an emerging tension between the media and the government.[1] Literacy was widespread in America, with over half of the white men able to read. The illiterates often could hear newspapers read aloud at local taverns. By the mid-1760s, there were 24 weekly newspapers in the 13 colonies (only New Jersey was lacking one), and the satirical attack on government became common practice in American newspapers.[2][3] The French and Indian war (1757–63) was the featured topic of many newspaper stories, giving the colonials a broader view of American affairs. Benjamin Franklin, already famous as a printer in Philadelphia published one of the first editorial cartoons "Join, or Die" calling on the colonies to join together to defeat the French. By reprinting news originating in other papers, colonial printers created a private network for evaluating and disseminating news for the whole colonial world. Franklin took the lead, and eventually had two dozen newspapers in his network.[4] The network played a major role in organizing opposition to the Stamp Act, and in organizing and embolding the Patriots in the 1770s.[5]

Colonial newspaper networks played a major role in fomenting the American Revolution, starting with their attack on the Stamp Act of 1765.[6] They provided essential news of what was happening locally and another colonies, and they provided the arguments used by the patriots, to Voice their grievances such as "No taxation without representation!"[7] The newspapers also printed and sold pamphlets, such as the phenomenally successful Common Sense (1776), which destroyed the king's prestige and jelled Patriot opinion overnight in favor of independence.[8] Neutrality became impossible, and the few Loyalist newspapers were hounded and ceased publication when the war began. However the British controlled important cities for varying periods of time, including New York City, 1776 to 1783. They sponsored a Loyalist press that vanished in 1783.[9]

New nation, 1780s-1820s

With the formation of the first two political parties in the 1790s, Both parties set up national networks of newspapers to provide a flow of partisan news and information for their supporters. The newspapers also printed pamphlets, flyers, and ballots that voters could simply drop in the ballot box.

By 1796, both parties had a national network of newspapers, which attacked each other vehemently. The Federalist and Republican newspapers of the 1790s traded vicious barbs against their enemies.[10]

The most heated rhetoric came in debates over the French Revolution, especially the Jacobin Terror of 1793–94 when the guillotine was used daily. Nationalism was a high priority, and the editors fostered an intellectual nationalism typified by the Federalist effort to stimulate a national literary culture through their clubs and publications in New York and Philadelphia, and through Federalist Noah Webster's efforts to simplify and Americanize the language.[11]

At the height of political passion came in 1798 as the Federalists in Congress passed the four Alien and Sedition Acts. The fourth Act made it a federal crime to publish "any false, scandalous, or malicious writing or writings against the Government of the United States, with intent to defame... Or to bring them... into contempt or disrepute." Two dozen men were charged with felonies for violating the Sedition Act, chiefly newspaper editors from the Jeffersonian Republican Party. The act expired in 1801.[12]

Second Party System: 1830s-1850s

Both parties relied heavily on their national network of newspapers. Some editors were the key political players in their states, and most of them filled their papers with useful information on rallies and speeches and candidates, as well as the text of major speeches and campaign platforms.

Third Party System: 1850s-1890s

Newspapers continued their role as the main internal communication system for the Army-style campaigns of the era. The goal was not to convince independents, who are few in number, but to rally all the loyal party members to the polls by making them enthusiastic about the party's platform, and apprehensive about the enemy.

Nearly all weekly and daily papers were party organs until the early 20th century. Thanks to Hoe's invention of high-speed rotary presses for city papers, and free postage for rural sheets, newspapers proliferated. In 1850, the Census counted 1,630 party newspapers (with a circulation of about one per voter), and only 83 "independent" papers. The party line was behind every line of news copy, not to mention the authoritative editorials, which exposed the 'stupidity' of the enemy and the 'triumphs' of the party in every issue. Editors were senior party leaders, and often were rewarded with lucrative postmasterships. Top publishers, such as Horace Greeley, Whitelaw Reid, Schuyler Colfax, Warren Harding and James Cox were nominated on the national ticket. After 1900, William Randolph Hearst, Joseph Pulitzer and other big city politician-publishers discovered they could make far more profit through advertising, at so many dollars per thousand readers. By becoming non-partisan they expanded their base to include the opposition party and the fast-growing number of consumers who read the ads but were less and less interested in politics. There was less and less political news after 1900, apparently because citizens became more apathetic, and shared their partisan loyalties with the new professional sports teams that attracted larger and larger audiences.[13][14]

Progressive era

Magazines were not a new medium but they became much more popular around 1900, some with circulations in the hundreds of thousands of subscribers. Thanks to the rapid expansion of national advertising, the cover price fell sharply to about 10 cents.[15] One cause was the heavy coverage of corruption in politics, local government and big business, especially by Muckrakers. They were journalists in the Progressive Era (1890s-1920s) who wrote for popular magazines to expose social and political sins and shortcomings. They relied on their own investigative journalism reporting; muckrakers often worked to expose social ills and corporate and political corruption. Muckraking magazines–notably McClure's–took on corporate monopolies and crooked political machines while raising public awareness of chronic urban poverty, unsafe working conditions, and social issues like child labor.[16]

New Deal era

Most of the major newspapers in the larger cities were owned by conservative publishers and they turned hostile to liberal President Franklin D Roosevelt by 1934 or so, including major chains run by William Randolph Hearst. Roosevelt turned to radio, where he could reach more listeners more directly. During previous election campaigns , the parties sponsored nationwide broadcasts of major speeches. Roosevelt, however, gave intimate talks, person-to-person, as if he were in the same room sitting next to the fireplace. His rhetorical technique was extraordinarily effective. However, it proved very hard to duplicate. Young Ronald Reagan, beginning a career in as a radio broadcaster and Hollywood star, was one of the few to match the right tone, nuance, and intimacy that Roosevelt had introduced.[17]

In peacetime, Freedom of the press was not an issue for newspapers. However radio presented the new issue, for the government control the airwaves and licensed them. The Federal Communications Commission ruled in the "Mayflower decision" in 1941 against the broadcasting of any editorial opinion, although political parties could still purchase airtime for their own speeches and programs. This policy was replaced in 1949 by the "Fairness Doctrine" which allowed editorials, if opposing views were given equal time.[18]

Television era: 1950-1980s

Television arrived in the American home in the 1950s, and immediately became the main campaign medium. Party loyalties had weakened and there was a rapid growth in the number of independents. As a result candidates Paid less attention to rallying diehard supporters and instead appealed to independent-minded voters. They adopted television advertising techniques as their primary campaign device. At first the parties paid for long-winded half-hour or hour long speeches. By the 1960s, they discovered that the 30-second or one-minute commercial, repeated over and over again, was the most effective technique. It was expensive, however, so fund-raising became more and more important in winning campaigns.[19]

New media era: since 1990

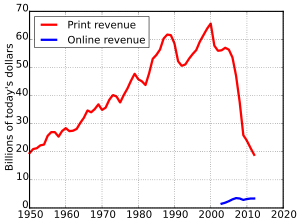

Major technological innovations transformed the mass media. Radio, already overwhelmed by television, transformed itself into a niche service. It developed an important political dimension based on Talk radio. Television survived with a much reduced audience, but remained the number one advertising medium for election campaigns. Newspapers Were in desperate trouble; most afternoon papers closed, and most morning papers barely survived, as the Internet undermined both their advertising and their news reporting.

The new social media, such as Facebook and Twitter, made use first of the personal computer and the Internet, and after 2010 of the smart phones to connect hundreds of millions of people, especially those under age 35. By 2008, politicians and interest groups were experimenting with systematic use of social media to spread their message among much larger audiences than they had previously reached.[21][22]

As political strategists turn their attention to the 2016 presidential contest, they identify Facebook as an increasingly important advertising tool. Recent technical innovations have made possible more advanced divisions and subdivisions of the electorate. Most important, Facebook can now deliver video ads to small, highly targeted subsets. Television, by contrast, shows the same commercials to all viewers, and so cannot be precisely tailored.[23]

See also

- American election campaigns in the 19th century

- History of American newspapers

- Mass media

- Political journalism

- Social media and political communication in the United States

- Talk radio

Notes

- ↑ Alison Olson, "The Zenger Case Revisited: Satire, Sedition and Political Debate in Eighteenth Century America." Early American Literature (2000) 35#3 pp: 223-245. online

- ↑ David A. Copeland, Colonial American Newspapers: Character and Content (1997)

- ↑ William David Sloan, and Julie Williams, The Early American Press, 1690-1783 (1994)

- ↑ Ralph Frasca, "Benjamin Franklin's Printing Network and the Stamp Act," Pennsylvania History (2004) 71#3 pp. 403-419 in JSTOR

- ↑ David Copeland, "'Join, or die': America's press during the French and Indian War." Journalism History (1998) 24#3 pp: 112-23 online

- ↑ Arthur M. Schlesinger, "The colonial newspapers and the Stamp Act." New England Quarterly (1935) 8#1 pp: 63-83. online

- ↑ Richard L. Merritt, "Public Opinion in Colonial America: Content Analyzing the Colonial Press." Public Opinion Quarterly (1963) 27#3 pp: 356-371. in JSTOR

- ↑ Winthrop D. Jordan, "Familial Politics: Thomas Paine and the Killing of the King, 1776." Journal of American History (1973): 294-308. in JSTOR

- ↑ Mott, American Journalism: A History, 1690-1960 pp 79-94

- ↑ Marcus Daniel, Scandal and Civility: Journalism and the Birth of American Democracy (2009)

- ↑ Catherine O'Donnell Kaplan, Men of Letters in the Early Republic: Cultivating Forms of Citizenship 2008)

- ↑ Walter Berns, "Freedom of the Press and the Alien and Sedition Laws: A Reappraisal," Supreme Court Review (1970) pp. 109-159 in JSTOR

- ↑ Richard Lee Kaplan, Politics and the American press: the rise of objectivity, 1865-1920 (2002) p. 76

- ↑ Mark W. Summers, The Press Gang: Newspapers and Politics, 1865-1878 (1994)

- ↑ Peter C. Holloran et al. eds. (2009). The A to Z of the Progressive Era. Scarecrow Press. p. 266.

- ↑ Herbert Shapiro, ed., The muckrakers and American society (Heath, 1968), contains representative samples as well as academic commentary.

- ↑ Douglas B. Craig, Fireside Politics: Radio and Political Culture in the United States, 1920-1940 (2005) excerpt

- ↑ Susan L. Brinson (2004). The Red Scare, Politics, and the Federal Communications Commission, 1941-1960. Greenwood. p. 34.

- ↑ D. M. West, Air Wars: Television Advertising and Social Media in Election Campaigns, 1952-2012 (2013).

- ↑ "Trends & Numbers". Newspaper Association of America. 14 March 2012. Retrieved 18 September 2012.

- ↑ Juliet E. Carlisle, and Robert C. Patton, "Is Social Media Changing How We Understand Political Engagement? An Analysis of Facebook and the 2008 Presidential Election," Political Research Quarterly (2013) 66#4 pp 883-895. in JSTOR

- ↑ Eli Skogerbø & Arne H. Krumsvik, "Newspapers, Facebook and Twitter: Intermedial agenda setting in local election campaigns," Journalism Practice (2015) 9#3 DOI:10.1080/17512786.2014.950471

- ↑ Shane Goldmacher, "Facebook the Vote: The social network at the center of American digital life could become the epicenter of the presidential race," National Journal Magazine June 13, 2015

Further reading

Surveys

- Blanchard, Margaret A., ed. History of the Mass Media in the United States, An Encyclopedia. (1998)

- Brennen, Bonnie and Hanno Hardt, eds. Picturing the Past: Media, History and Photography. (1999)

- Caswell, Lucy Shelton, ed. Guide to Sources in American Journalism History. (1989)

- Cull, Nicholas John, David Culbert and David Welch, eds. Mass Persuasion: A Historical Encyclopedia, 1500 to the Present (2003) 479pp; Worldwide coverage

- Daly, Christopher B. Covering America: A Narrative History of a Nation's Journalism (University of Massachusetts Press; 2012) 544 pages; identifies five distinct periods since the colonial era.

- Emery, Michael, Edwin Emery, and Nancy L. Roberts. The Press and America: An Interpretive History of the Mass Media 9th ed. (1999), standard textbook

- Kotler, Johathan and Miles Beller. American Datelines: Major News Stories from Colonial Times to the Present. (2003)

- McKerns, Joseph P., ed. Biographical Dictionary of American Journalism. (1989)

- Mott, Frank Luther. American Journalism: A History of Newspapers in the United States, 1690–1960 (3rd ed. 1962). major reference source and interpretive history.

- Nord, David Paul. Communities of Journalism: A History of American Newspapers and Their Readers. (2001)

- Paneth, Donald. The encyclopedia of American journalism (1983)

- Pride, Armistead S. and Clint C. Wilson. A History of the Black Press. (1997)

- Schudson, Michael. Discovering the News: A Social History of American Newspapers. (1978).

- Sloan, W. David, James G. Stovall, and James D. Startt. The Media in America: A History, 4th ed. (1999)

- Startt, James D. and W. David Sloan. Historical Methods in Mass Communication. (1989)

- Streitmatter, Rodger. Mightier Than the Sword: How the News Media Have Shaped American History (3rd ed. 2011) excerpt; 1997 edition online

- Vaughn, Stephen L., ed. Encyclopedia of American journalism (Routledge, 2007)

Historical eras

- Humphrey, Carol Sue. The Press of the Young Republic, 1783–1833 (1993) online

- Kaplan, Richard Lee. Politics and the American press: the rise of objectivity, 1865-1920 (2002)

- Pasley. Jeffrey L. "The Tyranny of Printers": Newspaper Politics in the Early Republic (2001) online review

- Summers, Mark Wahlgren. The Press Gang: Newspapers and Politics, 1865–1878 (1994) online

Recent

- Berry, Jeffrey M. and Sarah Sobieraj. The Outrage Industry: Political Opinion Media and the New Incivility (2014); focus on talk radio and partisan cable news

- Blake, David Haven. Liking Ike: Eisenhower, Advertising, and the Rise of Celebrity Politics (Oxford UP, 2016). xvi, 281 pp.

- Bobbitt, Randy. Us Against Them: The Political Culture of Talk Radio (Lexington Books; 2010) 275 pages. Traces the history of the medium since its beginnings in the 1950s and examines its varied impact on elections through 2008.

- Fiske, John, and Black Hawk Hancock. Media Matters: Race & Gender in US Politics (Routledge, 2016).

- Gainous, Jason, and Kevin M. Wagner. Tweeting to Power: The Social Media Revolution in American Politics (Oxford Studies in Digital Politics) (2013) excerpt

- Graber, Doris A. Mass media and American politics (2009); widely cited textbook

- Levendusky, Matthew. How Partisan Media Polarize America (2013)

- Street, Paul, and Anthony R. Dimaggio, eds. Crashing the tea party: Mass media and the campaign to remake American politics ( Routledge, 2015).

- Stromer-Galley, Jennifer. Presidential Campaigning in the Internet Age (2014) excerpt

- West, D. M. Air Wars: Television Advertising and Social Media in Election Campaigns, 1952-2012 (2013).