Martyrs of Compiègne

| The Martyrs of Compiègne | |

|---|---|

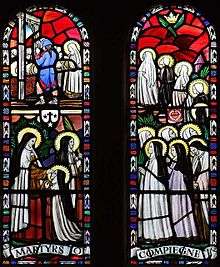

Stained glass window in the Church of Our Lady of Mount Carmel, Norfolk, England | |

| Born | 1715–1760 |

| Died | 17 July 1794, Place du Trône (modern day Place de la Nation), Paris, France |

| Martyred by | The Committee of Public Safety of the National Convention of Revolutionary France |

| Venerated in | Carmelite Order |

| Beatified | 27 May 1906, by Pope Pius X |

| Feast | 17 July |

| Notable martyrs | Blessed Teresa of St. Augustine, O.C.D. |

The Martyrs of Compiègne were the 16 members of the Carmel of Compiègne, France: 11 Discalced Carmelite nuns, three lay sisters, and two externs (tertiaries of the Order, who would handle the community's needs outside the monastery). During the French Revolution, they refused to obey the Civil Constitution of the Clergy of the Revolutionary government, which mandated the suppression of their monastery. They were guillotined on 17 July 1794, during the Reign of Terror and buried in a mass grave at Picpus Cemetery.

Imprisonment and execution

During the anti-clericalism of the Revolution, the monasteries and convents were suppressed. Consequently, the nuns were arrested in June 1794, during the Reign of Terror. They were initially imprisoned in Cambrai, along with a community of English Benedictine nuns, who had established a monastery for women of their nation there, since monastic life had been banned in England since the Reign of Henry VIII. Learning that the Carmelites were daily offering themselves as victims to God for the restoration of peace to France and the Church, the Benedictines regarded them as saintly.

The Carmelite community was transported to Paris, where they were condemned as a group as traitors and sentenced to death. They were sent to the guillotine on 17 July 1794. They were notable in the manner of their deaths, as, at the foot of the scaffold, the community jointly renewed their religious vows and sang the Veni Creator Spiritus, proper to this occasion.[1] One of the nuns then began to sing a hymn as she mounted the steps of the scaffold, which the rest of the community took up. Accounts vary as to the hymn they used. Some accounts state that they sang the Salve Regina, accorded a special place in the Carmelite Order;[2] more recently it has been argued that they sang Psalm 117, the Laudate Dominum, the psalm sung at the foundation of a new Carmelite monastery.[3] They continued their singing as, one by one, they mounted the scaffold to meet their death. The novice of the community, Sister Constance, was the first to die, then the lay Sisters and externs, and so on, ending with the prioress, Mother Teresa of St. Augustine, O.C.D.

When the Reign of Terror ended only days after their martyrdom, the English nuns credited the Carmelites with stopping the Revolution's bloodbath and with saving the Benedictines from annihilation. The nuns of Cambrai preserved with devotion, as the holy relics of martyrs, the secular clothes the Carmelites had been required to wear before their arrest, and which the jailer forced on the English nuns after the Carmelites had been killed. The Benedictines were still wearing them when, on 2 May 1795, they were at last allowed to return to their homeland, where they became the community of Stanbrook Abbey.

The martyrs are commemorated on that date in the Calendar of Saints of the Carmelite Order.

Veneration

Terrye Newkirk, in a book on the subject published in 2000, recounts the influence of their deaths:

On 17 July 1794, in the closing days of the Reign of Terror led by Robespierre, sixteen Carmelite nuns of the Catholic Church were guillotined at the Barrière de Vincennes (now the Place de la Nation) in Paris. They were buried in a common grave at the Picpus Cemetery, where a single cross today marks the remains of 1,306 victims of the guillotine.

A mere handful of the French Revolution's victims, they have commanded the attention of historians, hagiographers, authors, playwrights, composers, and librettists for two hundred years. In the course of the 20th century, the Martyrs of Compiègne have been the subject of a massive scholarly history, a German novella, a French play, a film, and Francis Poulenc's opera Dialogues of the Carmelites. In 1902, Pope Leo XIII declared the nuns Venerable, the first step toward canonization. They were later beatified by Pope Pius X in May 1906: Carmelites celebrate the memory of the prioress, Blessed Teresa of St. Augustine (Lidoine), and her fifteen companions on 17 July, and Catholics may adopt them as patrons. The bicentenary of their death was observed in 1994; many are petitioning for their canonization.[4]

Legacy in the arts

In 1931, the German convert, Gertrud von Le Fort, published a novella which was inspired by the events of their deaths, Die Letzte am Schafott (English: The Last One at the Scaffold). This later inspired a play written by the French Catholic writer, Georges Bernanos. The English translation of the novella was published in 1933 under the title Song at the Scaffold.[5]

Francis Poulenc's 1957 opera Dialogues of the Carmelites is based on the story of the Martyrs; the libretto is based on a scheme by Bernanos but it was written by Poulenc.

List of the martyrs

The martyrs consisted of 14 nuns and lay sisters (O.C.D.), and two externs:

Choir Nuns

- Mother Teresa of St. Augustine, prioress (Madeleine-Claudine Ledoine) b. 1752

- Mother St. Louis, sub-prioress (Marie-Anne [or Antoinett] Brideau) b. 1752

- Mother Henriette of Jesus, ex-prioress (Marie-Françoise Gabrielle de Croissy) b. 1745

- Sister Mary of Jesus Crucified (Marie-Anne Piedcourt) b. 1715

- Sister Charlotte of the Resurrection, ex-sub-prioress and sacristan (Anne-Marie-Madeleine Thouret) b. 1715

- Sister Euphrasia of the Immaculate Conception (Marie-Claude Cyprienne) b. 1736

- Sister Teresa of the Sacred Heart of Mary (Marie-Antoniette Hanisset) b. 1740

- Sister Julie Louise of Jesus, widow (Rose-Chrétien de la Neuville) b. 1741

- Sister Teresa of St. Ignatius (Marie-Gabrielle Trézel) b. 1743

- Sister Mary-Henrietta of Providence (Anne Petras) b. 1760

- Sister Constance, novice (Marie-Geneviève Meunier) b. 1765

Lay Sisters

- Sister St. Martha (Marie Dufour) b. 1742

- Sister Mary of the Holy Spirit (Angélique Roussel) b. 1742

- Sister St. Francis Xavier (Julie Vérolot) b. 1764

Externs

- Catherine Soiron b. 1742

- Thérèse Soiron b. 1748

See also

- Book of the First Monks

- Carmelite Rule of St. Albert

- Constitutions of the Carmelite Order

- Christian martyrs

- Discalced Carmelites

- Secular Order of Discalced Carmelites

References

- ↑

Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "The Sixteen Blessed Teresian Martyrs of Compiègne". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "The Sixteen Blessed Teresian Martyrs of Compiègne". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. - ↑ Bunson, Matthew E. (April 2007). "They Sang All the Way to the Guillotine". Catholic Answers. Vol. 18 (No. 4).

- ↑ Bush, William (1999). To Quell the Terror: The mystery of the vocation of the sixteen Carmelites of Compiègne guillotined July 17, 1794. Washington, D.C.: ICS Publications.

- ↑ Newkirk, Terrye, O.C.D.S. (2000). The Mantle of Elijah: The Martyrs of Compiègne as Prophets of the Modern Age. Washington, D.C.: ICS Publications. ISBN 0-935216-51-0.

- ↑ published by Sheed & Ward, London, 1933

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Martyrs of Compiègne. |

- On the history and spirit of Carmel. ICS Publications.