Margaret of Burgundy, Dauphine of France

| Margaret of Burgundy | |

|---|---|

| Dauphine of France; Duchess of Guyenne | |

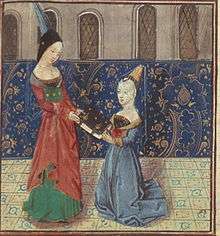

Christine de Pizan presents her book to Margaret | |

| Born | December 1393 |

| Died |

February 1442 Paris, France |

| Spouse |

Louis, Dauphin of France, Duke of Guyenne Arthur, Count of Richmond |

| House | House of Valois-Burgundy |

| Father | John the Fearless |

| Mother | Margaret of Bavaria |

Margaret of Burgundy (French: Marguerite; December 1393 – February 1442), also known as Margaret of Nevers, was Dauphine of France and Duchess of Guyenne as the daughter-in-law of King Charles VI of France. A pawn in the dynastic struggles between her family and in-laws during the Hundred Years' War, Margaret was twice envisaged to become Queen of France.

Early life

Born in late 1393, Margaret was the eldest child and the first of six daughters of John the Fearless and Margaret of Bavaria. Her father was, at the time, Count of Nevers and heir apparent to the Duchy of Burgundy ruled by his father, Philip the Bold. On 9 July 1394, Duke Philip and his mentally unstable nephew, King Charles VI of France, agreed that the former's first grandchild would marry the latter's son and heir apparent, Dauphin Charles. Following their formal betrothal in January 1396, Margaret was known as "madame la dauphine".[1] She and her sisters, described by a contemporary as "plain as owls",[2] grew up in an "affectionate family atmosphere" in the ducal residences of Burgundy, and were close to their paternal grandmother, Countess Margaret III of Flanders.[3]

First marriage

The death of her eight-year-old fiancé in early 1401 forced Margaret's grandfather and Charles' mother, Isabeau of Bavaria, to arrange a new union in the wake of Armagnac–Burgundian Civil War. In Paris in May 1403, it was agreed that Margaret would marry the new Dauphin of France, Duke Louis of Guyenne.[1] A double marriage took place at the end of August 1404,[4] as part of Philip the Bold's efforts to maintain a close relationship with France by ensuring that the next Queen of France would be his granddaughter.[1] Margaret married Dauphin Louis, while her only brother, Philip the Good, married Louis' sister Michelle.[5] Philip the Bold did not live long enough to see his grandchildren's marriages consummated. He died in 1404, and was succeeded by Margaret's father.[4] The French Italian author Christine de Pizan dedicated The Treasure of the City of Ladies to the young Dauphine, in which she advised her about what she had to learn and how she should behave; the manuscript may have even been commissioned by the Dauphine's father.[6]

It was not until June 1409 that the marriages were consummated, according to Jean Juvénal des Ursins, after which Margaret moved to the decadent court of her mother-in-law.[4] Margaret soon became a pawn in the struggle between two belligerent fractions, the Armagnacs and the Burgundians, who aspired to control her husband. Their childless marriage ended with Louis' death in 1415.[6] The young widow was rescued with some difficulty from Armagnac-controlled Paris.[3] She then returned to Burgundy, living there for a few years with her unmarried sisters alongside their mother. Upon their father's assassination in 1419, Philip the Good became Duke of Burgundy.[3]

Second marriage

.jpg)

Margaret's father-in-law died in 1422, and the English occupied a part of France in the name of his infant grandson, King Henry VI of England, who was to succeed him according to the Treaty of Troyes. At the same time, Margaret's brother-in-law Charles VII claimed the crown for himself. In early 1423, Philip the Good entered into an alliance with Duke John V of Brittany and Henry's regent, John of Lancaster, 1st Duke of Bedford. He intended to reinforce the alliance by arranging marriages of his sisters, Anne and Margaret, with the Duke of Bedford and the Duke of Brittany's younger brother Arthur, Count of Richmond, respectively.[2]

Margaret was far from enthusiastic about remarrying and attempted to postpone or prevent the marriage by complaining that Arthur was still imprisoned by the English and that all her sisters had married dukes. As the former Dauphine of France who still used the title of Duchess of Guyenne, she claimed that a count was too far beneath her in rank.[2] Philip had to send his trusted servant, Renier Pot, as a special ambassador to Margaret. Pot explained to her the necessity of an alliance with Brittany and told her that Bedford had created Arthur Duke of Touraine. Per Philip's instructions, Pot told Margaret that, still being a fairly young widow, she ought to marry and have children soon, more so because Philip himself was now a childless widower. She eventually yielded, and the marriage was celebrated on 10 October 1423.[2]

Arthur soon became a very influential person at the royal court in Paris, and staunchly worked in the interests of Burgundy, especially during his marriage to Margaret. Burgundy and Brittany eventually changed sides, joining Charles VII in his fight against the English. Margaret proved to be a devoted wife, protecting her husband when he fell out with Charles VII and managing his estates while he was at the battlefield. She returned with him to Paris when the French regained control of the city in 1436. Little is known about her life after 1436. She died childless in Paris in February 1442. In her will, a copy of which is preserved in the archives of Nantes, she asked that her heart be buried at a Picardy shrine called Notre-Dame de Liesse. Both her widower and brother, however, were too busy to carry out her final request. Arthur remarried within a year; both his subsequent marriages were also childless.[3]

Ancestry

| Ancestors of Margaret of Burgundy, Dauphine of France | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

- 1 2 3 Vaughan, Richard (2002). Philip the Bold: The Formation of the Burgundian State. Boydell Press. pp. 91–92. ISBN 0-85115-915-X.

- 1 2 3 4 Vaughan, Richard (2002). Philip the Good: The Apogee of Burgundy. Boydell Press. p. 10. ISBN 0-85115-917-6.

- 1 2 3 4 Morewedge, Rosemarie Thee (1975). The Role of Woman in the Middle Ages: Papers of the Sixth Annual Conference of the Center for Medieval and Early Renaissance Studies. State University of New York Press. pp. 97–98, 114–115. ISBN 1-4384-1356-4.

- 1 2 3 Vaughan, Richard (2002). John the Fearless: The Growth of the Burgundian Power. Boydell Press. p. 246. ISBN 0-85115-916-8.

- ↑ Adams, Tracy (2010). The Life and Afterlife of Isabeau of Bavaria. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 17–18. ISBN 978-0-8018-9625-5.

- 1 2 Wade Labarge, Margaret (1997). A Medieval Miscellany. McGill-Queen's Press. p. 41. ISBN 0-7735-7401-8.

Further reading

- Autrand, Françoise. Charles VI le roi fou. ISBN 2-213-01703-4